The Recapture, Consciousness Let Live Moments Longer, Which, in Truth, Only Offers Turmoil (The Last War in Albion Book Two Part Thirty-Two: Eschatology and Rebellion)

|

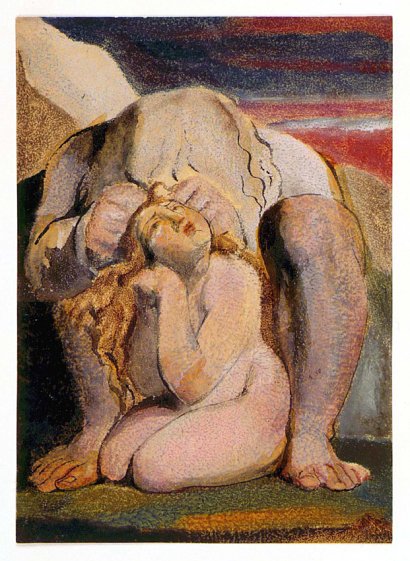

| Figure 957: The frontispiece to The Book of Ahania, showing Urizen’s murder of Ahania. (By William Blake, 1795) |

Previously in The Last War in Albion: William Blake, who contains within himself at least one entire past War in Albion, wrote compellingly of the importance of opposition in forward progress.

But as mentioned, by this standard Blake had no true friends; only those who, like Catherine, respected and pitied him. He wrote in mindful opposition to writers like Swedenborg and Milton, but both were dead by the time he addressed them, their replies to him limited to his own dreams and visions. He existed singularly within his time; and perhaps within any other. Given this, it is perhaps no surprise that he turned his vision inward, making a rival of himself to serve in place of the one the world would and could not provide. Within himself, however, Blake found far more than mere Contraries, a notion Blake was quick to move beyond, if indeed the simplistic alchemic model of unifying opposites was ever anything but an element of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’s satire. Certainly by the time of The Book of Urizen he had come to be more skeptical of the idea, hence the opposition of Los and Urizen being not a means by which Urizen is redeemed but a crucial step in creation’s fall into base materialism and the ensnarement of the world in the horrid net of religion. And much of Blake’s prophetic work in the period displays the same themes. From 1793-95 Blake produced two three-book myth cycles – the Continental Prophecies (America a Prophecy, Europe a Prophecy, and The Song of Los, which consists of two poems, “Africa” and “Asia,” that bookend the first two prophecies) and The Book of Urizen along with its two revisions/sequels The Book of Ahania and The Book of Los, across which he developed the early fundamentals of his mythology. And these are shot through with failed and frustrated oppositions: Orc’s faltering revolution in America, Enitharmon’s corrupted ascension in Europe, and both the failed revolt of Urizen’s son Fuzon and the destruction of his Emanation Ahania in The Book of Ahania.

Blake’s sense of doom and futility in this period is impossible to escape. He fashioned himself a prophet, yes, but his prophecies augured nothing good. Urizen’s tyranny seems inescapable, with every avenue of resistance doomed to sputter out or turn against itself. Even the grim eschatology of an unrelenting march towards doomsday would seem in some ways more optimistic than the utter despair of The Book of Urizen, which ends with a description of how “Beneath the Net of Urizen; / Perswasion was in vain; / For the ears of the inhabitants, / Were wither’d, & deafen’d, & cold; / And their eyes could not discern, / Their brethren of other cities.” The end, after all, is at least a form of escape and change. Blake, however, saw no escape or hope within his visions, writing in one of his notebooks in 1793 that “I say I shant live five years And if I live one it will be a Wonder.”…

Blake’s sense of doom and futility in this period is impossible to escape. He fashioned himself a prophet, yes, but his prophecies augured nothing good. Urizen’s tyranny seems inescapable, with every avenue of resistance doomed to sputter out or turn against itself. Even the grim eschatology of an unrelenting march towards doomsday would seem in some ways more optimistic than the utter despair of The Book of Urizen, which ends with a description of how “Beneath the Net of Urizen; / Perswasion was in vain; / For the ears of the inhabitants, / Were wither’d, & deafen’d, & cold; / And their eyes could not discern, / Their brethren of other cities.” The end, after all, is at least a form of escape and change. Blake, however, saw no escape or hope within his visions, writing in one of his notebooks in 1793 that “I say I shant live five years And if I live one it will be a Wonder.”…

You were supposed to be getting Shabcast 18 this week… but it vanished into the ether, owing to a malicious and inexplicable failure of my recording software. The Mailer Daemon collected it and conducted it to internet Hades. It was great too. I had Gene Mayes and (at last!) Jon Wolter in, and we chatted about Umberto Eco, Jorge Luis Borges, Italo Calvino, etc, in a podcast that was a lot sillier, funnier and more ribald than the subject matter really warranted. But, as I say, it is lost forever, doomed to live on only in the memories of the three men who experienced it… which, in a way, makes it all the more precious. One day, it will be the most sought of all lost Jack Graham-related media, and take on a near-mystical reputation, rather like London After Midnight, or Orson’s cut of Ambersons. I actually remember very little about it, as I was somewhat drunk and we were recording in the wee small hours here in Britain, and I spent most of the discussion in a haze of fatigue and mild inebriation. I seem to recall that we talked about the hip-hop musical Hamilton, which apparently at least one podcast listener is desperate to hear me talk about. Well, that listener lost their one and only chance. They’ll never hear what I said. Not even the bit where the three of us imagined a hip-hop musical about Garibaldi, written by Umberto Eco, and I said I’d go to the theatre heavily armed and force the cast to perform for me at gunpoint.

You were supposed to be getting Shabcast 18 this week… but it vanished into the ether, owing to a malicious and inexplicable failure of my recording software. The Mailer Daemon collected it and conducted it to internet Hades. It was great too. I had Gene Mayes and (at last!) Jon Wolter in, and we chatted about Umberto Eco, Jorge Luis Borges, Italo Calvino, etc, in a podcast that was a lot sillier, funnier and more ribald than the subject matter really warranted. But, as I say, it is lost forever, doomed to live on only in the memories of the three men who experienced it… which, in a way, makes it all the more precious. One day, it will be the most sought of all lost Jack Graham-related media, and take on a near-mystical reputation, rather like London After Midnight, or Orson’s cut of Ambersons. I actually remember very little about it, as I was somewhat drunk and we were recording in the wee small hours here in Britain, and I spent most of the discussion in a haze of fatigue and mild inebriation. I seem to recall that we talked about the hip-hop musical Hamilton, which apparently at least one podcast listener is desperate to hear me talk about. Well, that listener lost their one and only chance. They’ll never hear what I said. Not even the bit where the three of us imagined a hip-hop musical about Garibaldi, written by Umberto Eco, and I said I’d go to the theatre heavily armed and force the cast to perform for me at gunpoint. James Bond: Vargr #6

James Bond: Vargr #6

In preparation for the May launch of our Kickstarter for it, we’re running excerpts of Neoreaction a Basilisk. This is from quite early in the book while I’m introducing my three main characters of Eliezer Yudkowsky, Mencius Moldbug, and Nick Land.

In preparation for the May launch of our Kickstarter for it, we’re running excerpts of Neoreaction a Basilisk. This is from quite early in the book while I’m introducing my three main characters of Eliezer Yudkowsky, Mencius Moldbug, and Nick Land. Yes, that’s really how it ends; the most secret of histories is always is the real one. That gnostic gap between what we know happened and what happened. The facts are these:

Yes, that’s really how it ends; the most secret of histories is always is the real one. That gnostic gap between what we know happened and what happened. The facts are these: