World Enough and Time Review

As an excuse to let Peter Capaldi exclaim “a Mondasian Cyberman!” it’s a solid one. This is not an inherently less worthwhile pursuit than getting Ysanne Churchman back to do the Alpha Centauri voice, so let’s roll with it. After all, the other Peladon-related angle to work here is “the Monster of Peladon to Dark Water’s Curse,” and we wouldn’t want to get snarkily contrarian in the first paragraph, now would we?

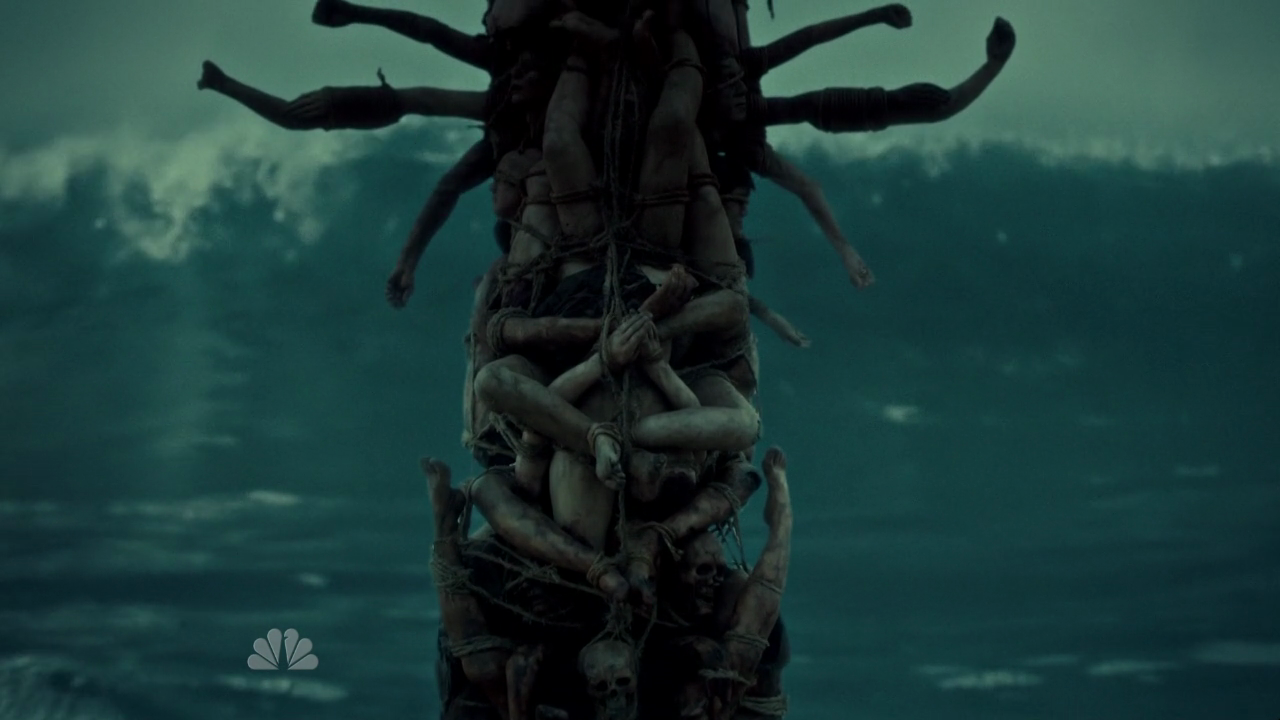

After all, there’s a lot that’s good to outright brilliant. Stripping the Mondasian Cybermen back to the medical horror that inspired Kit Pedler the weekend after the US Senate unveiled its plan to fund a tax cut for the wealthy by murdering poor is probably the second most audaciously on the nose classic series deep cut that Doctor Who could have done this week. (Third is Brexit of Peladon; first, of course, would be a Paradise Towers sequel with a prominent scene about fire.) It’s beautifully executed – Rachel Talalay nails the horror as you’d expect, and Moffat’s eye for the macabre has never been finer than the volume knob. The Mondasian Cybermen are exquisitely creepy, and the extended buildup of their iconography before Bill’s eventual conversion is absolutely delicious. But past that, pretty much everything there is to say about it hinges entirely on The Doctor Falls.

That, notably, wasn’t true of Dark Water, which hinged on the shock twist of killing Danny in the cold open, delivering the astonishing volcano confrontation in its first half before moving on to its expertly inevitable assembly of the promotional pieces. Here, however, we have an episode that really is just forty-five minutes devoted to getting the audience caught up with Doctor Who Magazine. No, it’s not a problem that the show is made for the other 100% of the audience, but equally, that’s the hundred percent of the audience that doesn’t know who the Mondasian Cybermen are and may or may not remember John Simm’s last appearance eight years ago. It’s just that, well, that’s the episode – the efficient and moody delivery of a cliffhanger by assembling a bunch of pre-announced elements into what’s basically the only shape they could ever have fit into. The only potential surprise is John Simm getting his Leon Ny Taiy on with a comedy prosthetic, which is admittedly absolutely delightful.

If this is a triumph, it’s going to be because of how The Doctor Falls plays with what it’s been given. Certainly the trailer makes it look as though it’s a more complex matter than “Missy is evil after all,” which you’d expect. I mean, Moffat has always been fond of mirroring past lines and structures, so the implicit inversion of Dark Water in which the Doctor is trying to get Missy to be his friend again instead of the other way around is intelligent. And it’s unlikely that the cowriter of Into the Dalek is going to declare Missy beyond redemption. This absolutely has the ability to turn into something extraordinary.…

The Patreon is healthily above $320 now

The Patreon is healthily above $320 now

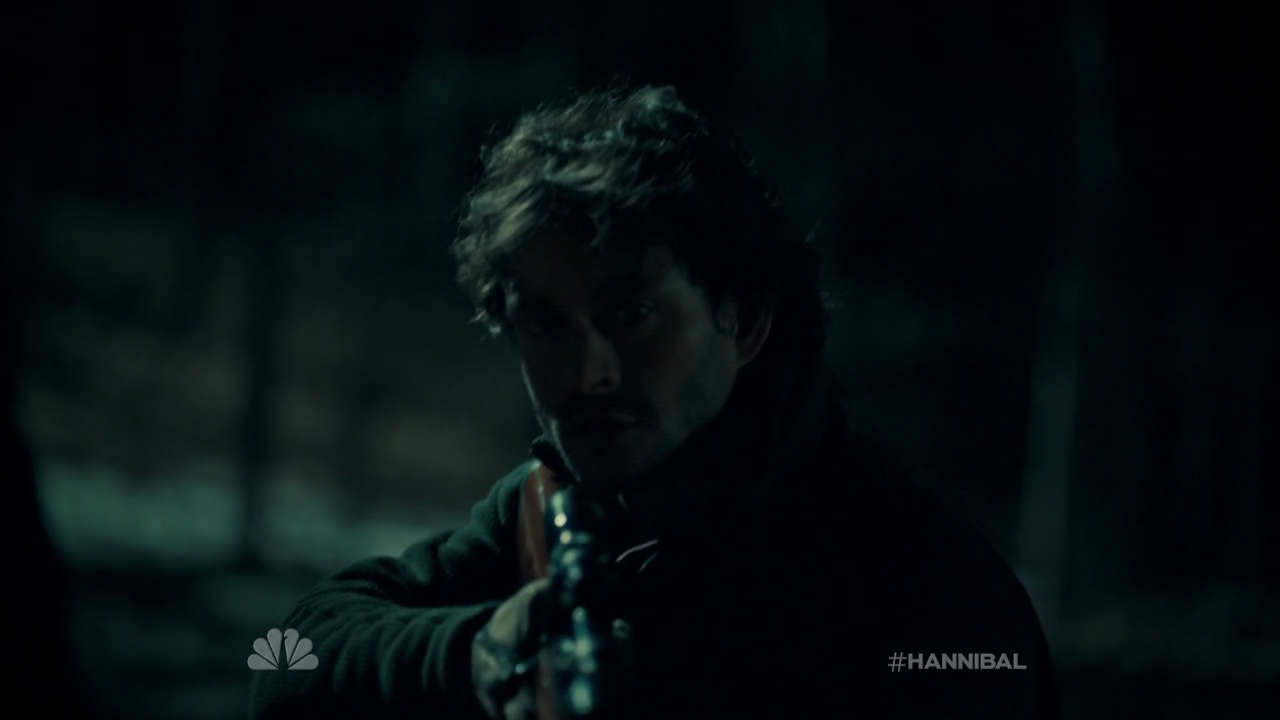

RELEVÉS: Properly “removes,” but best understood in the sense of a relief pitcher, with the idea being that the course replaces the previous one. In practice, it is the big set-piece course, and so functioning much the same way that “Rôti” did.

RELEVÉS: Properly “removes,” but best understood in the sense of a relief pitcher, with the idea being that the course replaces the previous one. In practice, it is the big set-piece course, and so functioning much the same way that “Rôti” did.

RÔTI: Roast, specifically roasted game birds, but in this case likely a straightforward case of “and now we arrive at the big centerpiece courses.”

RÔTI: Roast, specifically roasted game birds, but in this case likely a straightforward case of “and now we arrive at the big centerpiece courses.”