This is the first of ten parts of Chapter Five of The Last War in Albion, covering Alan Moore’s work on Future Shocks for 2000 AD from 1980 to 1983. An ebook omnibus of all ten parts, sans images, is available in ebook form from Amazon, Amazon UK, and Smashwords for $2.99. If you enjoy the project, please consider buying a copy of the omnibus to help ensure its continuation

Most of the comics discussed in this chapter are collected in The Complete Alan Moore Future Shocks.

PREVIOUSLY IN THE LAST WAR IN ALBION: Realizing that he’ll be hard-pressed to make it as a writer-artist, Alan Moore turned his focus in 1980 towards scripting comics for other writers, first getting work on Marvel UK’s

Doctor Who Weekly and Star Wars:

The Empire Strikes Back Monthly writing short back-up strips featuring secondary characters from those franchises. But Moore was quick to augment that with other work, most notably for IPC Media’s

2000 AD…

“Sound clarions of war. Call Vala from her close recess in all her dark deceit.” – William Blake, The Four Zoas

And yet it also suggests that Moore is not best served by writing in such narrow genres as “Star Wars tie-ins” or “Doctor Who stories that don’t feature Doctor Who.” It is both telling and compelling, then, that a far larger body of Alan Moore’s early work comes in the form of bespoke short stories for 2000 AD published under the header of Tharg’s Future Shocks. It is not that this format allowed unfettered creativity by any measure. But it was a structure that allowed Moore to stretch his creative wings, as well as to work with a compelling variety of artists.

|

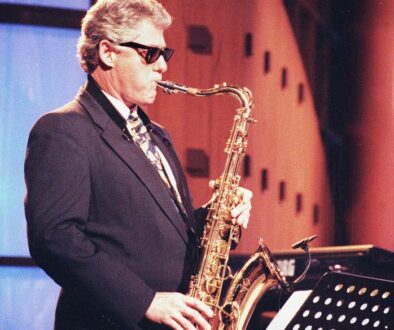

Figure 182: So thoroughly collected is

Alan Moore’s work that even his Star Wars

strips have found a home. |

The dawn of Moore’s work for 2000 AD marks a subtle but significant change to the nature of the War’s narrative. Prior to this point in the narrative the material under discussion has been only sporadically collected. Roscoe Moscow and The Stars My Degradation have been put up for free on the Internet with Moore’s consent, Maxwell the Magic Cat has a long-out-of-print reprint series, and Moore’s Star Wars material has found a home in an omnibus published by Dark Horse Comics (although with Disney recently acquiring both Star Wars and Marvel Comics there’s a question mark over how long that will remain in print. But from this point on the overwhelming majority of the texts that constitute the War are readily available in print, and thus form a coherent and reasonably well-known body of texts, all of which were published in the same general period.

As it happens, the period in question coincides almost perfectly with the portion of Alan Moore’s career in which he wrote for IPC’s 2000 AD, a period which lasted from July of 1980 through April of 1986. Within this roughly six-year period, however, there are two distinct phases. The first of these goes from July of 1980, with the publication of his first story, “Killer in the Cab,” in Prog 170 through to September of 1983, when his final one-off story, the two-page “Look Before You Leap!” appeared in Prog 332. For the bulk of this period Moore’s career consisted of essentially three jobs. He was always at one time or another writing something for Marvel UK – initially the Doctor Who Weekly work, then his Star Wars strips, and finally his run on Captain Britain in various magazines. He was also still doing the two jobs he started in 1979 – the Sounds comics (The Stars My Degradation by this point) and Maxwell the Magic Cat. Finally, he did a smattering of one-off (and occasionally two-off) strips for 2000 AD, mostly, though not entirely, under their Tharg’s Future Shocks banner. This provided a stable career plan for Moore for just under two years.

|

Figure 183: Prog 170 of 2000 AD (then called

2000 AD and Tornado), featuring Alan Moore’s

first work for the magazine (Cover by Mike

McMahon, 1980) |

The first significant change to this setup came in March of 1982, when he added another gig to the rotation, writing a pair of strips for Warrior every month. This was counterbalanced by him handing writing duties on The Stars My Degradation off to Steve Moore, giving £10 of his £35-a-week pay to him. On March 19th, 1983 things changed again as he began work on Skizz, his first ongoing strip for 2000 AD The same day, Sounds published the last installment of The Stars My Degradation. Prog 308, in which Skizz debuted, also featured “The Reversible Man,” the first of Moore’s short stories to go out under the Time Twisters banner instead of as one of Tharg’s Future Shocks, and a story that marks a visible shift in his style. Of his remaining sixteen short stories for 2000 AD, nine went out under the Time Twisters banner. For the next six months Moore was frequently contributing two stories per issue – an installment of Skizz and a short story. The end of Skizz in August of 1983 was quickly followed by the publication of Moore’s first work for the American market, Saga of the Swamp Thing #20. At this point, Moore ceased dong short stories for IPC, and moved into the second phase of his work for them, in which he did exclusively long-form work – first a series of stories featuring his characters of DR & Quinch in the first half of 1984, and then, starting in July of 1984, The Ballad of Halo Jones.

As already discussed, a chronological history of Moore’s work in this period is difficult, requiring as it does several passes over the same few years. Further complicating it is the Warrior material – even though Moore broke with Warrior not long before its demise in early 1985, all of the comics he had been writing for Warrior survived, with two of them jumping with Moore to America. And, of course, as of 1983 his career included a sizable US component that rapidly came to provide a majority of his income and take up an increasing share of his time, making it impossible to differentiate cleanly between UK and US phases of his career. Nevertheless, two major strands of thought about this period present themselves. On the one hand is the perspective of what pieces of Moore’s work have the most direct impact on the War. In this regard three things present themselves: Moore’s run on Saga of the Swamp Thing, and his Marvelman and V for Vendetta strips in Warrior, all of which are landmark moments in the War due in a large part to their international reputation. Due to the complex publication histories of Marvelman and V for Vendetta, however, it is not prudent to deal with them quite this early in the tale, although they will haunt the narrative from this point on.

|

Figure 184: Prog 466 of 2000 AD, featuring

Moore’s last significant work for the magazine

(Cover by Ian Gibson, 1986) |

Beyond that, these three landmarks do not exist in a vacuum, but are moments of Moore’s developing career. From this perspective, the key event is not the publication of any of these, but instead The Ballad of Halo Jones, which marks a significant dividing line in both Moore’s career and the War. Its abandonment in April of 1986 marks the point at which Moore’s work in the mainstream British comics industry ceases, and thus marks a clear transition. Furthermore, a month after the third book of The Ballad of Halo Jones wrapped in April of 1986 the first major battle of the War broke out with the publication of Watchmen #1 by DC Comics. The magnitude of this event means that everything from this point in the narrative until the outbreak of open hostilities must be taken as leading up to that moment.

It is best, therefore, to take this portion of the narrative in two phases. First, the events that led to Alan Moore getting a call from DC Comics in May of 1983 offering him a job writing Saga of the Swamp Thing. Second, the path Moore’s career took from there to the publication of Watchmen #1 three years later. And it is worth framing this in terms of the magazine that is the most consistent feature of Moore’s work in this era: 2000 AD.

|

Figure 185: The first prog of 2000 AD, its cover dominated

by the free “space spinner” toy offered with it. (1977) |

The first issue, or prog (short for “programme,” as the covers refer to themselves) of 2000 AD was cover-dated February 26th, 1977, but the history of the magazine begins slightly earlier, in 1974. That was the year that D.C. Thompson, publishers of Starblazer and The Beano, debuted Warlord. Warlord was a shot in the arm for an essentially moribund British boys comics industry in which there had been few major innovations since Eagle in 1950. The fact that Eagle had itself entered a steady decline and been cancelled by new owners IPC in 1969, some five years earlier, did not stop it from being essentially the sole model for boys comics, especially at IPC, where the boys group was dominated by Jack Le Grand, a staunch traditionalist who was thoroughly uninterested in innovation or modernization. D.C. Thompson, on the other hand, broke through with Warlord, which, while still a war comic in the traditional mould, went for an increased degree of grit and violence that proved commercially successful.

|

Figure 186: Battle Picture Weekly #1,

John Wagner and Pat Mills’s first comic

for IPC (Cover artist unknown, 1975) |

Caught flat-footed, IPC hired a pair of freelancers, John Wagner and Pat Mills, to create a competitor. That magazine was Battle Picture Weekly. In order to avoid the stodginess in the boys group, the comic was actually created in secret in office space belonging to the girls group, where Mills and Wagner both also did work. Even there, they gave a sense of the iconoclastic cheek that they would bring to their more famous endeavors. Alan Moore suggests that their time on girls comics had led them to grow “cynical and possibly actually evil,” and fondly remembers a comic called The Blind Ballerina in the IPC magazine Jinty. The comic was on the whole accurately titled – it focused on a girl who wanted to become a ballerina despite being blind. As Moore puts it, perhaps with some embellishment, “John [Wagner] would just try to put her into increasingly worse situations. At the end of each episode you’d have have her evil Uncle saying, ‘Yes, come with me. You’re going out onto the stage of the Albert Hall where you’re going to give your premiere performance,’ and it’s the fast lane of the M1. And she’s sort of pirouetting and there’s trucks bearing down on her.”

|

Figure 187: Battle Picture Weekly‘s success hinged on Pat

Mills and John Wagner’s instinctive understanding that

people wanted to read about 16th century tallships beating

the crap out of Nazis (Writer and artist uncredited, Battle

Picture Weekly #1, 1975) |

This gleeful love of the inappropriate served Wagner and Mills well in creating a suitably violent war comic, and Battle Picture Weekly #1 comes off as a piece of precision engineering. D-Day Dawson featured a strapping, square-jawed soldier who is critically injured so that there’s a bullet lodged in his chest that will, eventually, work its way to his heart and kill him. The medic who diagnoses him, however, is quickly killed in a shell attack while Dawson escapes. Dawson proceeds to rejoin the front line, declaring to himself that “the Germans had better watch out… they’re up against a man with nothing to lose!” This, then, became the occasion for a comic in which Dawson took increasingly absurd and heroic risks to protect his men. Lofty’s One-Man Luftwaffe features a British soldier who, in an impressive series of contrivances, manages to infiltrate the Luftwaffe so that he can “give the Hun a real pasting – from the inside!” The Flight of the Golden Hinde provided the comic’s most inventively weird premise – a reconstruction of Sir Francis Drake’s ship that was out to sea when the war broke out joins the war efforts and single-handedly takes down a Nazi ship. Battle Honours provided a patina of respectability by retelling stories of great (that is, violent) British military victories, while Day of the Eagle (the title unapologetically nicked from Frederick Forsyth’s The Day of the Jackal) provided a change of pace with an espionage story, and got given the middle two-page spread (printed in color). Rat Pack, singled out by Garth Ennis as one of his favorite strips, is an unalloyed Dirty Dozen knock-off by Gerry Finley-Day, who would go on to work substantively on 2000 AD, and Judge Dredd co-creator Carlos Ezquerra, featuring four hardened criminals recruited to become a team of crack commandos. And The Terror Behind The Bamboo Curtain, in which Sado, a grotesquely stereotyped Japanese soldier sends British POWs into a complex maze of death traps known as the Bamboo Curtain, leading “big Jim Blake, a crack jungle fighter” to deliberately get sent behind the curtain so he can stop Sado’s sadistic games.

|

Figure 188: The Bootneck Boy impresses a recruiting

sergeant with the working class grit he learned growing up

in “the tough northern town of Tynecastle.” (Writer and

artist uncredited, Battle Picture Weekly #1, 1975) |

It is The Bootneck Boy, however, which most exemplifies the sort of approach that Mills and Wagner could pull off. In it, a scrawny lad named Danny Budd tries to join the marines, but is rejected. Budd is an archetypal Mills/Wagner hero – a scrappy iconoclast who breaks the rules and gets rewarded for it. The strip takes care to establish Budd’s inherent goodness – on the first page he rescues an old man trapped under the rubble of a bombed out building. But despite his good deeds he’s abused by his uncle at work, and gets into a fight with his cousin Ron (nicknamed Piggy) when Ron insults his deceased father’s medals. After stoically enduring a beating from his uncle, Danny goes to deliver some coal, at which point he’s accosted by a group of boys who blame him for something or other Piggy did. Danny takes on all three boys, shouting at a Marine who rushes in to help him to “keep off, Mister! They started this fight – an’ Im gonna finish it meself!” The Marine, who turns out to be the recruiting sergeant who rejected him at the start of the strip, is so impressed with Danny’s fighting that he changes his mind and accepts him into the Marines, where his adventures continue.

|

Figure 189: Danny Budd is thoroughly unphased

by his beating. (Writer and artist uncredited, Battle

Picture Weekly #1, 1975) |

What is significant about The Bootneck Boy is not merely its repeated excuses for violence, but the nature of its hero – from “the tough northern town of Tynecastle.” Danny is an explicitly working class lad whose heroism comes not only from his good nature but from his disregard for illegitimate authority and his common sense. It’s notable that he’s beaten by his uncle for fighting with Piggy – the same sort of corporal punishment that working class kids suffered routinely in The Beano and The Dandy. But instead of being a violent end to a carnivalesque inversion of social roles, the beating is just a badge of honor Danny wears as he stubbornly holds to his own moral code. It’s not plucky inventiveness or a tendency to “keep calm and carry on” that saves the day, but hard-edged working class grit and bottle. In other words, the working class audience of the comic is reassured that they, not the people in charge, are the real heroes of the story.

Battle Picture Weekly was an unambiguous success, much to the chagrin of Le Grand and the old guard (although this may have had as much to do with Pat Mills’s impressive pay package, which exceeded that of John Sanders, who hired him as it did with any actual creative differences). Appropriately, Mills and Wagner quickly found more work within IPC. Wagner was tapped to lead an only semi-successful revamp of Valiant, an old adventure magazine that was, despite Wagner’s efforts, merged into Battle in 1976. Mills, on the other hand, was tasked with creating another book that would go even further in the direction pioneered by Warlord and Battle Picture Weekly, to be called Action, and debuting in February of 1976. [continued]

January 2, 2014 @ 3:27 am

Prog 170 of 2000 AD (then called 2000 AD and Tornado), featuring Alan Moore's first work for IPC

No, there's 'A Holiday in Hell', a seldom if ever reprinted Tharg's Future Shock in the 1980 2000AD Sci-Fi Special, which I think came out a couple of months earlier or possibly simultaneously-at-the-same-time as prog 170.

However, everyone involved agrees that it was the first thing he actually wrote for IPC

January 2, 2014 @ 9:24 am

I had thought "first work" to be a phrase flexible enough to encompass "first accepted," but I've rewritten the caption to be completely accurate. (Holiday in Hell itself is three weeks off from being described.)

February 16, 2015 @ 10:04 pm

Loving reading about 2000AD – ah the days I would run as a kid to the grocer's to pick up my copy! Wonderful weekly doses of wild Sc-fi.