This is the eighth of ten parts of Chapter Five of The Last War in Albion, covering Alan Moore’s work on Future Shocks for 2000 AD from 1980 to 1983. An ebook omnibus of all ten parts, sans images, is available in ebook form from Amazon, Amazon UK, and Smashwords for $2.99. If you enjoy the project, please consider buying a copy of the omnibus to help ensure its continuation.

Most of the comics discussed in this chapter are collected in The Complete Alan Moore Future Shocks.

Previously in The Last War in Albion: After an initial period of promise and originality, Moore’s future shocks began to fade into repetitiveness as the limits of the format became increasingly and painfully clear…

“We have camera eyes that speed up, slow down, and even reverse the flow of time, allowing us to see what no one prior to the twentieth century had ever seen — the thermodynamic miracle of broken shards and a puddle gathering themselves up from the floor to assemble a half-full wineglass.” -Grant Morrison

|

Figure 242: “The Wages of Sin” even recycles the final

joke of “They Sweep the Spaceways,” with the major

difference being that Talbot arranged his panels

vertically and Leach horizontally. (c.f. Figure 235)

(From “The Wages of Sin,” written by Alan Moore, art

by Bryan Talbot, in 2000 AD #257, 1982) |

But many other stories in the period are flatter at best. “A Second Chance,” a two-pager in which the last man on Earth finds a woman, is utterly devoid of any point. “All of Them Were Empty,” in which a siege on a American truck stop is revealed to be conducted by sentient cars wanting a fill-up, is similarly uninspiring, as is “No Picnic,” in which a man is buried alive on Easter Island to become one of the famed heads. And when Moore did hit gold, it was often by rehashing his own previous work. One of his best stories of 1982, “The Wages of Sin,” is a redo of “They Sweep the Spaceways,” this time focusing on the training that would-be galactic conquerers go through. It’s not that it is a pale imitation of “They Sweep the Spaceways.” In fact, its jokes are a step sharper, and the art by Bryan Talbot is superlative. But it’s still just a refinement of an earlier strip.

For the most part this stretch of Moore’s work is characterized by a heavy reliance on straightforward twist endings. Some of these are reasonably clever – “The Beastly Beliefs of Benjamin Blint”,” for instance, uses the basic twist of the classic Twilight Zone episode “The Eye of the Beholder,” whereby the eponymous Benjamin Blint tells his therapist about the horrible creature that periodically appears to him. The strip shows several such encounters, between a typically square-jawed man and a suitably horrible looking creature. The final panel reveals that Blint is in fact the monstrous creature, haunted by the “hideous” ordinary human, who Blint finally admits can’t possibly be real, because there just isn’t room in the real world for creatures as stomach-turning and loathsome as that.” “The Bounty Hunters,” four issues later, is a similarly straightforward twist ending – soldiers hunting a homicidal shape-changing alien grow increasingly jumpy, suspecting the planet’s foliage, each other, and even the planet itself of being the alien. Eventually they admit defeat and return to their ship, which turns out to be the alien in question and promptly devours him.

|

Figure 243: Moore demonstrates the absurdity of

Future Shocks‘ twist endings some two dozen strips

prior to stopping writing them. (From “Twist Ending,”

written by Alan Moore, art by Paul Neary, in 2000

AD #246, 1982) |

Both of these stories are broadly competent, but they are straight-laced twist ending stories with little to trade on other than the hope that their twist is clever. In practice, it usually was, or at least clever enough to work. If anything, Moore was likely to end up being a bit too clever, as in the straightforwardly named “Twist Ending,” in which a writer is interviewed by a journalist who is convinced the writer is secretly an alien. The eponymous twist ending is that while the writer is not an alien, his typewriter is in fact a sentient alien life form who is the real author of works like “Invasion of the Death Gerbils.” It makes about as much sense as one would expect, and, given the title, seems almost a deliberate mockery of the twist ending formula for Future Shocks.

But mock the format as he might have, the truth is that Moore was largely unable to escape it in this period. Indeed, it’s telling that Moore’s tendency to self-plagiarize in this period struck even within these generic twist-ending strips. “Return of the Thing,” in Prog 265, uses almost the exact same twist as “The Beastly Beliefs of Benjamin Blint,” this time having a strip that appears to be about a woman cowering in horror as a massive alien monster lumbers into her house, only to have it turn out that her concern was simply that she hadn’t finished making dinner yet, and that the alien is in fact her husband returning home. It’s clever, but it’s also the second time in sixteen weeks that Moore has relied on the trick of having what appears to be a monster in fact be something else. And it’s a not entirely clear or coherent strip either – it’s never quite clear why the husband enters his house by kicking the door down, for instance.

But Moore’s stagnation is wholly understandable. The same month as “The Wages of Sin” came out, he picked up two regular strips in Warrior #1. Warrior was a young upstart of a magazine (hence it turning to largely untested talent for two of its launch titles), but it quickly established itself as a critical darling, and Moore’s career accelerated. As he puts it, “once 2000 AD and Marvel knew I was being given series work by somebody else, they became more inclined to give me series work as well.” But this isn’t quite true. Yes, Marvel UK gave him Captain Britain three months after Warrior #1. But IPC spent an entire year letting Moore write two-pagers about things like an exploration of a brick wall discovered at the edge of the universe that turns out to have some message written on it, which, after considerable effort, is revealed to be grafitti reading “Big George rules, OK?”. By the time they got around to offering him Skizz, he was on the cusp of winning his first Eagle award. (That year’s awards would prove quite a rebuke to IPC, who were essentially shut out. Brian Bolland’s victory as best artist was cold comfort, given that he had by that time made the jump to US comics, meaning that the only award they won was “Character Most Worthy of Own Title” for Judge Anderson. Another way to put it, of course, is that IPC’s only win was for what people wished they were doing instead of what they were doing. The rest of the awards went to Warrior, most notably to Alan Moore for his work on Marvelman.)

|

Figure 244: Moore dabbles in fumetti for the

relaunched Eagle (From “Trash,” written by

Alan Moore, art by Steve Arnstein, in Eagle

#3, 1982) |

Nor was IPC particularly interested in utilizing Moore elsewhere in its stable of magazines. The only other place it found to house Moore’s work was in their revived version of Eagle, where he contributed a pair of fumetti – “Trash!” and “Profits of Doom” – under the banner of The Collector, which provided Future Shocks-style short stories about various horrible and supernatural fates befalling collectors of things. The former concerned a man who throws out all of his grandmother’s papers and memories in a pique, only to be killed when the papers reincarnate in her house and drown him. The latter features a collector who cheats a man out of a valuable comic, which turns out to have never actually been published. The collector reads of himself in the comic, and is promptly eaten by tentacles from within the comic. The two stories are strong contenders for the most ephemeral and marginal work of Moore’s career, and show the degree to which IPC mostly used him for disposable filler.

This is one of the points where the overlapping chronology of Moore’s early work obscures the actual narrative. It is true that 2000 AD was among the first professional work Moore did as a pure writer – “Killer in the Cab” came out two weeks into Business As Usual for Doctor Who Weekly. But other than publishing there early on, essentially none of Moore’s big breaks took place in the magazine. Far from being Moore’s big break at long-form storytelling, Skizz was in fact the fourth ongoing strip he’d written, post-dating V for Vendetta and Marvelman by an entire year. In this light, Moore’s middle-period work for 2000 AD takes on a new tone. Moore – always confident of his abilities (as early as 1984 he was willing to casually proclaim that “there are maybe a dozen people in the Western world who know as much or more than I do about writing comics,” although he clarified that “this says more about the paucity of the medium than it does about my personal talents”) – must have chafed looking at Prog 240 and realizing that “A Cautionary Fable” wasn’t going to lead to him getting a regular strip because the magazine would rather give that honor to Tom Tully, who was busily penning the barely readable The Mean Arena.

|

Figure 245: Tom Tully had been with 2000 AD

since Prog #1 (From “Harlem Heroes,” written by

Tom Tully, art by Dave Gibbons, in 2000 AD #1,

1977) |

(To be fair to IPC, it is not clear they had a choice. Artist Robin Smith recalls that “Tully was one of those blokes who had this deal whereby they were entitled to have a story in so many titles,” meaning that, in effect, cancelling one of Tully’s numerous banal series was a pointless endeavor, as it would have to be replaced by another Tom Tully story.) To be crowded out by lesser writers even as Moore visibly proved himself with other companies can only have been a frustrating experience, especially given that 2000 AD was a magazine Moore had such regard for and so wanted to succeed at. And when IPC finally offered Moore a strip, it was as a sop after he pitched a Judge Dredd spin-off to be called Badlander. In other words, instead of being promoted on the basis of his talent, Moore was given a derisory promotion only when it was clear that he was agitating for one and unsatisfied with toiling on Future Shocks.

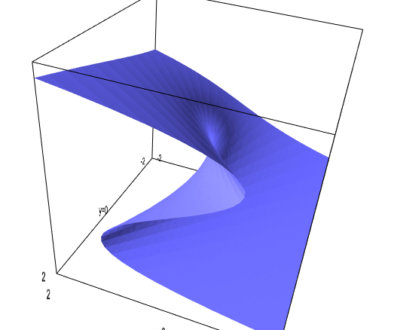

Regardless, acquiring his first regular strip for 2000 AD had demonstrable benefits for Moore’s writing, not least because it coincided with a new sort of short story format for the magazine, called Time Twisters. In some ways this turn was prefigured earlier – one of Moore’s better 1982 stories was “The Disturbed Digestions of Doctor Dibworthy,” a three-pager with art by dave Gibbons in which Doctor Dibworthy, staring at a piece of paper, feels himself on the verge of a great insight, at which point a horde of future versions of himself show up to implore him not to invent the time machine he’s about to come up with the idea for. Eventually, in horror, Dibworthy throws out the piece of paper, only to find himself on the verge of a similar insight in the flow patterns of his glass of Port. As is typical of Moore/Gibbons collaborations in 2000 AD, the story is a comedy, and Gibbons’s propensity for detail enables several panels of a small crowd of Dibworthys, all with suitably unique facial expressions and postures. But unlike Moore and Gibbons’s other short stories, there’s an undercurrent of deeper poignancy and horror to the story, and the twist ending, rather than being funny, is ever so slightly unnerving. In any case, Moore liked the character enough to bring him back in a proper Time Twisters ten months later, in which he continually attempts to change the past, only to be disappointed by his apparent failure when, in reality, his memories change with the past and he fails to notice the profound alterations to the room around him as he makes increasingly drastic alterations, starting with murdering an “obscure Turkish diplomat in 1057 A.D.” and escalating to killing King John prior to signing the Magna Carta and preventing the invention of the Steam Engine. The story ends with Dibworthy preventing the Big Bang, and being disappointed when “nothing happened. Nothing at all.”

|

Figure 246: The poignant “The Reversible Man”

marked a clear shift in the nature of Moore’s writing

for 2000 AD (From “The Reversible Man,” written

by Alan Moore, art by Mike White, in 2000 AD

#308, 1983) |

But while the first Dibworthy story shows the broad potential of what Moore could do when writing about time, it’s not until Prog 308 in March of 1983 that the renaissance of Moore’s later 2000 AD work truly kicks off. That issue contained both the first installment of Skizz, and his first proper Time Twister, a four-pager called “The Reversible Man.” This is, by most reckonings, also one of his best stories. The premise is simple enough – it’s just the events of a perfectly ordinary man’s life, only told in reverse so that his first memory is of getting up off the pavement, feeling a sharp pain, and then walking backwards with an ice cream cone that reforms and jumps up into his hand. As he was walking, he explains, “ice cream seemed to be dribbling off my tongue and re-filling the cone in my hand.” The story progresses as he gets bored of retirement and gets an office job (“the manager smiled and stole my gold watch,” he notes), disinters an old woman (his mother, in fact) from the cemetery and takes her to the hospital where she slowly recovers and moves in with him, watches as his children grow young and finally go off to the hospital with their mother, never to return, marries his wife (and thus has to move out), goes back to school (“it was very pleasant forgetting things that had never been any use to me, like Latin and chemistry,” he notes, with Moore’s relish at the line positively dripping off the page), and finally becomes an infant, at which point he’s slapped on the back and stops breathing.

Moore has commented of the story that it was “pathetically easy to write,” and that he was as a result surprised by its reception, speculating that its popularity was because “the events of our lives become dulled by reputation and it takes an unusual view of them for us to see life and its emotional implications anew,” disclaiming that the story’s success “had very little to do with me as a writer.” [continued]

February 20, 2014 @ 12:41 am

Gah! Don't you hate it when something written as a reply to a post is eaten by your browser! My apologies for the brevity of the following, but I'm having to summarise from memory.

I think we can take Moore's run on Future Shocks as not so much a critique of him as a writer but quite the opposite. He remained as their primary writer for so long precisely because he was good at writing them, and they were vital for 2000ad at the time for their use of filling in between other continuing stories, and making sure other artists were kept busy while waiting for other scripts or stories to begin. This is reinforced by the way that few, if any, of the artists assigned Moore during this period were try out artists. they were predominantly tried and tested IPC artists with long histories of meeting deadlines. And the ones that were new to 2000ad were experienced in their own right (Talbot already working on Luther Awkwright, and Neary being a former Editor in Chief of Marvel UK, and the person responsible for Alan Davies Captain Britain commission).

Moore's value as a writer is further underscored by some of his strips being assigned the all important and valued colour centre spread, something that traditionally was given to the most popular comic strip in 2000ad of the time (usually Judge Dredd). And because of the colouring process, these strips had to be prepared in advance of the black and white strips, so they were not last minute replacements.

In this light, I think we can say that Moore's belief that Skizz was given as a placatory measure because of his growing popularity elsewhere is probably correct.

It's also interesting to note, when the whole "plagiarism" aspect of the War is taken into account, that The Reversible Man was cited by some reviewers in the early 90's as being the basis of Martin Amis' Booker Prize runner up novel, Time's Arrow. (A novel that adopts the same idea of investigating a mans life when lived in reverse, but in the context of Time's Arrow being used to explore the Holocaust). Of course, both stories themselves can probably be traced back to F Scott Fitzerald's The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.

February 20, 2014 @ 2:04 am

Lots of people have written stories about living backwards. I found a list at io9 that is probably far from complete.

February 20, 2014 @ 4:35 am

while there have been a lot of "living backwards" stories, Amis' "Time Arrow" has a lot of similarities to Moore's story—regurgitating food, visiting a dying old person in hospital who slowly recovers, etc.

February 20, 2014 @ 4:46 am

Yes, as that list proves, hardly an original concept but, as in so much of his work, it's the skill and unpredictable turns of phrase which Moore employs that make it special. It's also unlikely that younger readers of 2000AD would have encountered the reverse time narrative before so, again, it does a good job of introducing a mind expanding premise within an ostensibly juvenile milieu.

This magpie approach to creating narrative is worthy of note as it becomes, as I'm sure Phil will detail, Moore's primary concern over the next stage of his career. There is nothing startlingly original about a retired hero regaining his memories and powers or a masked vigilante fighting an oppressive regime, it's the style and precision of Moore's prose that makes Marvelman and V for Vendetta the game-changers they undoubtedly were.

February 20, 2014 @ 4:55 am

Whether it was plagiarism or not what I found particularly galling at the time of publication of Time's Arrow was not only the sycophantic attitude of literary reviewers praising his 'startlingly original concept' (the same type of reviewer who would regularly dismiss Science Fiction novels as juvenile) but also Amis's disingenuous acceptance of that praise with no acknowledgement that he had appropriated the idea from any number of possible sources.

February 20, 2014 @ 8:22 am

"SF's no good," they bellow 'til we're deaf,

"But this looks good." "Well then, it's not SF!"

-Martin Amis's dad

February 20, 2014 @ 8:39 am

To be fair to IPC, it is not clear they had a choice. Artist Robin Smith recalls that “Tully was one of those blokes who had this deal whereby they were entitled to have a story in so many titles,”

The next obvious question is why? Clearly this wasn't standard procedure, so someone at IPC must have decided Tully was worth this arrangement.

February 20, 2014 @ 7:09 pm

“All of Them Were Empty,” in which a siege on a American truck stop is revealed to be conducted by sentient cars wanting a fill-up, is similarly uninspiring"

This sounds like the Stephen King short story 'Trucks', filmed as 'Maximum Overdrive". I think the original Swamp Thing artist did some art for King's Dark Tower books, which got increasingly metafictional.

February 20, 2014 @ 7:18 pm

Tully was presumably on the staff at IPC, and as the main writer of such seminal 60s/70s British comic strips as The Steel Claw and Roy of the Rovers would probably have had some clout. Certainly a lot of the stuff he wrote was a part of my own childhood, however bad some of it might turn out to be in hindsight.

February 21, 2014 @ 12:13 am

And yet Martin's dad was a huge James Bond fan, even going so far as writing a Bond novel under a pseudonym.

But knowing Kingsley, it was the masculinity/misogyny that appealed (the same that appalled Moore).

I realise the point regarding plagiarism and Time's Arrow, but thought t pertinent considering the accusations directed toward Morrison from Moore.

Phil, I know there's no such thing as a Pop between Realities for the last War in Albion, but are you going to explore the cultural impact of Alan Bleasdale's Boys from the Blackstuff and it's influence on Skizz?

"I've got me pride"/"Gizzus a job."

(Of course, the same exploration of cultural influence needs to be born in mind when we reach Morrison's Zenith, especially John Byrne's Tutti Frutti and Richard Wilson's manager, Eddie Clockerty.)