James and the Cold Gun

James and the Cold Gun

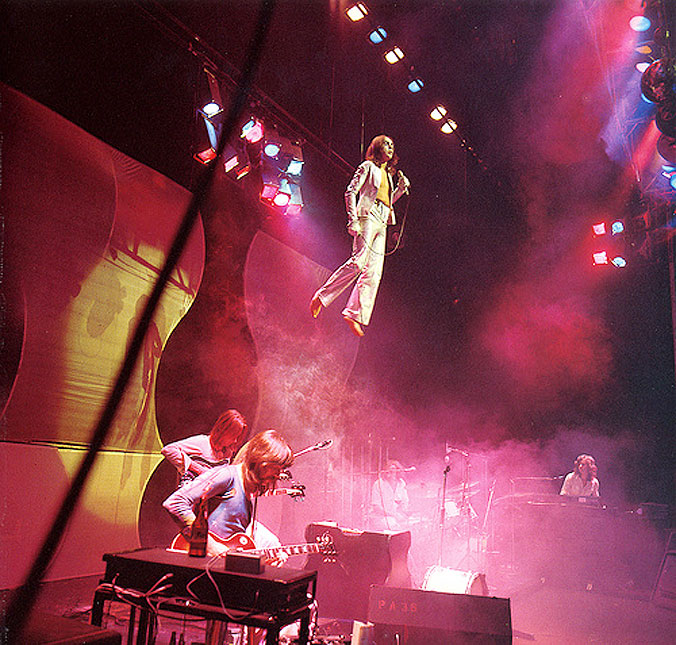

Hammersmith Odeon

I’ve recently set up a Patreon, which has gotten off to a good start with 14 Patrons. If you enjoy my work, consider pitching me some money over there. My financial situation is strained to say the least, and every bit helps. Plus you might get to read some writing you’ll enjoy. In the meantime, here’s “James and the Cold Gun.”

A ragtag group of session musicians is enveloped in an infernal red backlight, which makes good on its promise to swallow the entire stage. A cowgirl from some dark dimension swaggers onstage, posing in a black and gold robe for the presumably dumbfounded audience. For close to nine minutes, the cowgirl sweeps across the stage, wailing over the cacophony of her band and illustrating her lyrics with suitably on-the-nose gestures. It culminates, as any Chekov-honoring song featuring “gun” in the title does, with a murder, as the cowgirl blasts the life out of an adversary, each gunshot met beat-for-beat by accompanying drums. Contorting her body in a freakish victory dance, the cowgirl ends the song lifting a rifle above her head in triumph, as her audience roars its approval.

“James and the Cold Gun” is The Kick Inside’s showstopping number, Bush’s rockiest song. It features American western imagery at length (“it’s not there in the GIN/that makes you laugh long and loud”), guitars dominating the band, and Duncan Mackay’s organ weeping like it’s in the mix on a Dylan record. This potential international crossover appeal is probably why it was EMI’s original pick for Bush’s debut single until Bush vetoed these plans. It’s easy to see the pop promise EMI found in “James”: it’s closer to the rock that was in the charts. The song was popular among the pub-frequenting audiences of the KT Bush Band. Energetically, it’s closer to chart-topping hard rock acts like Queen than Bush’s courtship of more intricately formalist rock such as Genesis.

We may as well talk about Genesis, who were accustomed to giving the sort of performances Bush would stage for “James and the Cold Gun.” Prog rock’s affinity for jams and playing a single track at great length would manifest in astonishingly long improvs onstage. Peter Gabriel would don make-up and extravagant costumes and give a literary voice to the mirage of sound. It comes as no surprise this approach bears similarities to Bush’s stageshow. While not directly name-checked as an influence on Bush’s tour, Gabriel would come to play a part in her career soon enough.

There is another distinctive element of Genesis that Bush’s work inherits: Englishness. While the predominant trend in British rock was to pluck from American music to make it big, Genesis came from a school of art that looked to its homeland for its stories. There’s a pastoral quality to much of their music that’s more at home in a tradition with As You Like It than The Great Gatsby. English land and politics come into Gabriel-era Genesis songs quite often, and Bush’s nurturing relationship with British mythos bears similarities to this approach (which will come to a crescendo in “O England My Lionheart”).

pluck from American music to make it big, Genesis came from a school of art that looked to its homeland for its stories. There’s a pastoral quality to much of their music that’s more at home in a tradition with As You Like It than The Great Gatsby. English land and politics come into Gabriel-era Genesis songs quite often, and Bush’s nurturing relationship with British mythos bears similarities to this approach (which will come to a crescendo in “O England My Lionheart”).

Furthermore, the Englishness of Bush’s vocals is also similar to Genesis. In a 1985 interview, Bush distinguishes between British artists who sang in English accents (David Bowie and Roxy Music) and those who sang with American voices (she cites Elton John, Robert Palmer, and Robert Plant). Bush expresses a preference for the former tradition, perhaps liking the familiarity of it. Peter Gabriel fits into this tradition well enough, articulating syllable endings that Mick Jagger would spit across the vocal booth. When Bush works in disparate genres, she brings her own English vision to them (Bush’s vision of Englishness is of course deeply middle class and white. There’s a conspicuous absence of working class people in most of her music, although we’ll get to the exceptions soon enough).

This keeps “James” from being a white R&B track. Bush half-sings/half-speaks the lyrics, offering commentary and chewing the scenery like a lecturer in a pub: “they’re only lonely for the life that they led.” Her vocals just aren’t very American: there’s a focus on vocally bending words that you won’t find in the libidinous lyric-swinging of most rock bands. Bush’s vocals sound off in a way that could have made EMI’s plans for the song counterintuitive in practice.

The song itself is a rollicking ballad, staying in B flat minor for its entirety. “James” is one of the sillier Kick Inside tracks, and ostentatiously lacks depth. This isn’t a flaw as such — it’s a perfectly serviceable explosive number. Bush sings a Western pastiche, telling of “Genie, from the casino,” who’s “still a-waiting in her big brass bed.” The song is jokey in tone, with Bush urgently warning the hero James “you’re running away from humanity/you’re running out on reality!” She describes a Western that’s been abandoned by its hero. Her strategy of putting self-awareness into genre characters has been lightly subverted. In “James and the Cold Gun” she presents a genre that’s fallen apart in the absence of a protagonist. In his absence, Bush comes to both use his genre as a playground and mourn his departure.

So Bush has effectively co-opted a Western movie. What would have happened if she’d kowtowed to EMI and let “James and the Cold Gun” be her debut single? Perhaps she would have placed somewhere in the top 40: critics might have been ambivalent and not been pressured into seeing her as a force to be reckoned with like she was upon the release of “Wuthering Heights.” That song might have lost some of its inaugural power too, becoming a second single without months of buildup as a promo record. Alternatively, “James” might have had some minor popularity in the states. Bush might be a more successful American figure. We don’t know. But that’s one of the intrigues of Kate Bush: she makes her own way and will give any aesthetic territory a chance.

Recorded 1977 at London AIR Studios. Performed live on the Tour of Life in 1979. Personnel: Kate Bush — piano, vocals. Stuart Elliott — drums. David Paton — bass. Ian Bairnson — guitars. Duncan Mackay — organ.