Sat In Your Lap

We did it. I hit $300 on the Patreon because of your support. Thank you so much to everyone who pledged (all 98 of you),  shared the link, contributed to reaching the goals, or was just kind and supportive. This is quite literally life-changing for me. I can making a living off my passion without having to compromise financial security or my mental health. You people are amazing and I am indebted to you all. To be clear, $300 is a minimum though. I’m a disabled trans woman, and people will inevitably drop their pledges. Continued support would be great. But in the meantime, thank you. My life is better for your support.

shared the link, contributed to reaching the goals, or was just kind and supportive. This is quite literally life-changing for me. I can making a living off my passion without having to compromise financial security or my mental health. You people are amazing and I am indebted to you all. To be clear, $300 is a minimum though. I’m a disabled trans woman, and people will inevitably drop their pledges. Continued support would be great. But in the meantime, thank you. My life is better for your support.

Demo

Sat In Your Lap (single)

Sat In Your Lap (LP version)

MV

Dance rehearsal (fragment, Looking Good Feeling Fit)

The aftermath of Never for Ever was a period of burnout for Bush. Prone to depressive burnouts after the completion of projects, she found herself drifting into a nadir of fruitless ennui, which she deemed “the anti-climax after all the work.” Completing Never for Ever in May 1980, Bush, not for the last time, put significant space between herself and the public, taking a holiday after an exhausting several months of recording. By the time Never for Ever was released in September, Bush was only just recovering from her creative inertia. Her timing was auspicious, as Never for Ever not only became her first #1 LP in the UK but the country’s first ever #1 studio album by a female solo artist ever. Never for Ever’s success was accompanied by heaps of promotion by Bush, including the usual run of performing songs on talk shows as well as signing albums for hundreds of fans at a time. Now she had more creative agency than she had previously, touting Never for Ever as “the first [album] [she] could hand to people with a smile.” Kate Bush the prodigy who sang “Wuthering Heights” was already a distant memory, transforming into Kate Bush the great 1980s British songwriter.

Yet Bush’s listlessness and struggle to write songs persisted for some time. It’s not hard to see why — the stress of Never for Ever’s production and the attention of the British public would be enough to put a damper on anyone’s creative output. It took seeing other musicians at work to get her motivated again. In September, Bush and her boyfriend Del Palmer attended a Stevie Wonder concert at Wembley Arena. Wonder was in a period of creative renewal himself. Having recently turned out a rare Motown flop in the distinctively titled Journey Through “the Secret Life of Plants”, he’d rebuilt confidence with his delightful Hotter than July LP. The concert broke Bush out of her writer’s block — “inspired by the feeling of his music,” as she later wrote, Bush got back to work on her songs, and forged a path towards her next album.

Bush’s work to date was largely harmonic, built around what notes went together interestingly on the piano. Rhythm was secondary for her: it’s hard to think of a rhythmically powerful song on Bush’s first three albums. Her preparations for Kate Bush IV had thus far consisted of little bits of melody, but without a focal center. After the Wonder concert, she realized she needed to start her songwriting from the rhythm track upwards. At home, she programmed a rhythm into her Roland drum machine (according to my friend Marlo, the Roland on her demo from the period sounds like a CR-78, and woe to anyone who disagrees with Marlo on drum machines), and “worked in [a] piano riff to the hi-hat and snare.” A demo resulted: “Sat In Your Lap,” Kate Bush’s first solo production, was in its nascency.

“Sat In Your Lap” wasn’t always Bush’s first self-produced song. For a time, she entertained bringing in experienced producers, including long-standing David Bowie collaborator Tony Visconti, going so far as to spend a day in the studio with him. The collaboration went nowhere, and Visconti has grossly remarked “all I can remember is the Bush bum.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, Bush decided to take on the producer role herself, with the intensive collaboration of a series of engineers. The first set of sessions for the album that would be The Dreaming were staged at Townhouse Studios in May 1981. Her collaborating engineer was Hugh Padgham, a producer for Phil Collins and XTC known for the “gated drum” sound that would define 80s pop (compress the drums, use a recording console’s “gate” to remove their reverb, resulting in a kind of sound vacuum. See Phil Collins’ “In the Air Tonight”). Bush and Padgham’s time in Townhouse was productive yet short-lived. Padgham is rare among Bush collaborators in having negative feelings about working with her, grumbling about her tendency to overpack a mix and experiment rather than having a concrete, straightforward vision. After laying backing tracks for three songs, Padgham moved on, dissatisfied with his latest gig but having indelibly marked the sound of The Dreaming.

Bush’s ad-libs, piano riffs, and rhythm track came together quickly in the studio, quicker than any other song on The Dreaming. Having a drum-centric engineer like Padgham was incredibly useful for her, as the early recording of Bush’s rhythm track showed. “Sat In Your Lap” is heavily percussive, built around its drum sound and brass section (initially synthesized on a Yamaha CS-80). The partially syncopated drumbeat (“dum-DUM-dum-DUM”) is Preston Heyman’s most memorable to date, a fine translation of the demo. The frantic, almost pharyngeal rhythm track has a kick drum so guttural and suppressed (though not apparently gated) that it can easily be mistaken for one of Bush’s vocal onomatopoeias. The track’s sonic menagerie (Bush’s recurring motif of musical instruments as bodily extensions lives to a maniacal extent), a veritable ensemble of screams, tinny horns on the Fairlight CMI, swishing bamboo sticks (thanks to Paddy Bush and Preston Heyman) childlike whispers, “HO-HO-HO’s,” and bellows of “JUST when I think I’m king!”

What better to bring Bush out of a period of creative stagnation than a missive to psychological stagnation? Or even better, a tremendously loud, busy, and clamorous one. Amidst the song’s sheer volume is a narrative of inertia and stillness. Bush deploys a childlike whisper in the verses, a canny juxtaposition with the rhythm track’s masculine percussiveness, indicating juvenile trepidation as she watches adults go about their lives: “I see the people working/I see it working for them/and so I want to join them/but then I find it hurts me.” The verses are terse observations from an unmoving figure, grounded in a desire to catch up and have a powerful mind: “I see the people happy/so can it happen for me?,” “I want to be a lawyer/I want to be a scholar/but I really can’t be bothered,” “I want the answers quickly/but I don’t have no energy.”

The verses are similarly sclerotic, sticking to its home key and mode of Ab Dorian closely, with an incessant chord progression of i-VII (Abm7-Gb), a relatively conservative doublet of chords that seem paranoid about wandering away from the key’s tonic (limiting a verse to its key’s tonic and subtonic is uncharacteristically parsimonious for Bush), and even staying in 3/4 the whole time. The refrain sees a return to Bush’s harmonic and rhythmic weirdness. Her predilection for following up a key’s tonic chord with the tonic of the parallel key lives as ever, as she maneuvers from Ab minor’s IV chord (Db) to Ab major’s iv (Db minor). The refrain otherwise sticks to a fairly conventional Ab minor (IV-iv-i-IV), with a smattering of Bushian time signature changes (it mostly sticks to 4/4, with a bar in 2/4 at the tail end of “some say that knowledge is something sat/in your lap” and “ho, ho, ho”). The post-chorus breaks with Ab Dorian, modulating to Db Mixolydian (a major key alternative to Dorian mode) with “JUST when I think I’m KING!”, dallying with chords not present in the key (A) and owning its unified disjointedness.

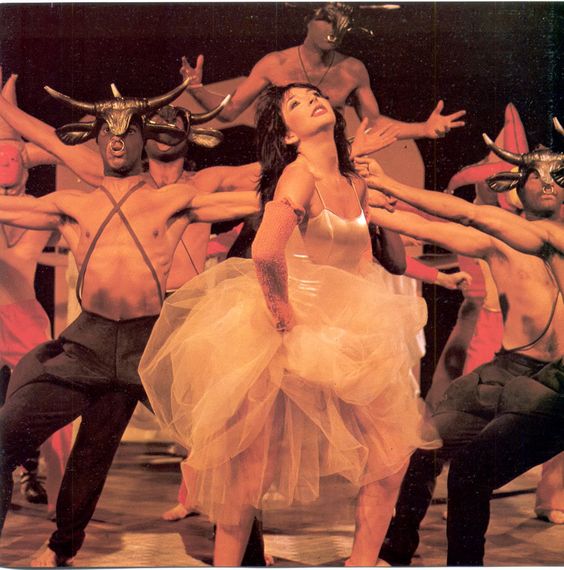

“Sat In Your Lap” conveys both frantic motivation and fearful inaction — it is enticed by the busy and productive activities of people and intimidated by the energy exerted in them, perhaps suggesting a character outwardly compelled to be a productive adult too soon (it’s possible Bush could relate). It is at once rapid, careening at 146 BPM, and petrified with fear. The music video (Bush’s first without director Keef Macmillan) swerves between stillness and freneticism. During the verses, Bush is mostly seated in a white dress, while the refrains see her cavorting with dancers in dunce caps. Former “gifted and talented” children drained by adults’ external compulsion to excel may encounter a kindred spirit in “Sat In Your Lap.” Yet even in its inertia lays a search — despite the emotional shutting down, the desperate need for knowledge and truth is genuine and constant.

The incessant refrain, consisting of Bush screaming (with occasional variations) “some say that knowledge is something sat in your lap/some say that knowledge is something that you never have,” makes the preoccupation with knowledge clear. Holy shit, says Bush, look at all this cool stuff adults do! And all these neat religious and philosophical paths! “Some say that heaven is hell/some say that hell is heaven!” Is anyone right? The sheer quantity of faiths can be incredibly disorienting to an adult. The comparable power that spirituality can have over a child is often formative.

Spirituality often works at a snail’s pace. Things that become deeply engrained in a young believer’s mind at an early age will only become clear to them several years later. A child confronted with gods can have a variety of emotional responses: indifference, awe, fear, befuddlement, joy. Sometimes a child is deeply moved by what they witness and feel. Yet with that, there can be complete physical inertia — shock and over-saturation, or interior silence and contemplation. For instance, the Hebrew Bible’s prophet Ezekiel responds to his first apocalyptic vision by sinking into days of catatonia. Bush’s answer to the mind-body problem is a symbiotic one — it’s an ouroboros, with no strict origin point, the body and the mind depending on one another. Once “Sat In Your Lap” taps into this idea of

Complicating this is the partial secularity of the song’s search. Her questions aren’t any less spiritual for it — some of the most spiritually complex people I’ve ever met are confirmed atheists, and Kate “I don’t think I’ve really found a niche” Bush hardly seems like a Bertrand Russell-esque non-believer. Ever the aesthete, Bush claims that she’s primarily drawn to the iconography of faith: “such powerful, beautiful, passionate images!” as she said of her Roman Catholic upbringing. Her first ever published writing was a poem about the Crucifixion. In a 1979 interview, she prodded a possible belief in a God, opining that God was “a label for people to put all their belief and love into,” and that putting such emotional effort into one’s relationships with people causes one to “reach an aim.” For all the theological crudeness of this idea (it boils down to little more than a hippie’s plea for everyone to just get along), Bush is (characteristically) unintentionally right. There’s a deep emotional center to faith and prayer. Contemplative and meditative traditions are built on unifying one’s emotional state with spirituality. This doesn’t make the experiences any less real — feelings are facts of life. An empirical understanding of any societal phenomena has to grasp its emotional basis: the values and emotions it appeals to.

Another animating tension of “Sat in Your Lap” is its emotional fluidity while nominally discussing knowledge: “some say that knowledge is something sat in your lap,” or knowledge is “something that you never have.” These are largely apophatic definitions of knowledge, defining it as an elusive force. The rampant emotiveness pervades a search for knowledge. “In my dome of ivory/a home of activity/I want the answers quickly/but I don’t have no energy” sees a desire for knowledge colliding with aporia and sensory overload. Without a clear path forward, sometimes the only trajectory is acceleration and exhaustion.

As the only answer to the unanswerable is sublime incoherence, the song’s coda is hermetic descent into sensory overload. Iconography blurs (“Tibet or Jeddah,” “to Salisbury/a monastery”) in a tendency that’s strong in the last couple verses, as Bush inverts Psalm 23 (“my cup, she never overfloweth”), dabbles in desert-dwelling, monasticism, cathedrals, and with “some grey and white matter,” the human brain (grey and white matter oversee the brain’s connection to the spinal cord). “Sat in Your Lap” concludes with inconclusiveness: its dance is in the terrifying glory of befuddlement. Asceticism is a cerebral process as well as physical: the brain responds to the body’s state. Bush is engaging with some genuinely fascinating systems of thought here: for all the approaches to the mind/body problem that have been formulated, responding to it with “isn’t scholastically-caused sensory overload a kind of asceticism?” is new.

Recorded at Townhouse Studio 2, Shepherd’s Bush in May 1981; mixed through June. Issued as a single 21 June 1981; released again as the opening track of The Dreaming on 13 September 1982, over a year later. Music video also released in July ’81. Like every other song on the album, never performed live. Kate Bush — vocals, piano, CMI, production. Hugh Padgham — engineer. Nick Launay — engineer (mixing). Preston Heyman — drums, bamboo sticks. Jimmy Bain — bass. Paddy Bush — backing vocals, bamboo sticks. Ian Bairnson — backing vocals. Gary Hurst — backing vocals. Stewart Avon-Arnold — backing vocals. Geoff Downes — CMI trumpets. Photo: Kindlight.

August 20, 2020 @ 11:54 am

Your content is really instructive. Keep posting.

October 22, 2021 @ 11:32 am

I always knew this song was a huge criticism against the educational system. I got happy to know someone else had the same opinion as I do.