Symphony in Blue

This essay was brought to you by 20 readers on Patreon.

Symphony in Blue

Xmas special

Tour of Life

The premiere track of Lionheart is a synecdoche of the entire album. “Symphony in Blue” is introspective, troubled, and, most importantly, aestheticist. Throughout these essays, we’ve hit on how despite the constraints of its production, Lionheart manages to says some intriguing things about stagefright, aesthetic and music as both a mode of survival and an abstract horror in its own right. Lionheart’s answers are more complex than the ones The Kick Inside offered, and adjusts the trajectory of future Bush albums.

“Symphony in Blue” is almost essayistic in its structure: it has two verses, two choruses, and a brief outro. Additionally, each verse is separated into two halves, each with a distinct focus. Each verse starts with a section about a color, and ends with a thesis on a sensation or emotion. The songs forms a series of propositions on the relationship between interior experience and aesthetic expression.

There’s been a strong visual component to Bush’s work in general work — she’s almost as famous for her music videos as she is for her songs. It’s impossible to imagine “Wuthering Heights” without its music videos. Her songwriting is frequently centered on visual concepts, and cinema is as big an influence on Bush as music is. This focus on performance and theatricality is key to Lionheart, as the predominant image in its music is that of the stage (“Hammer Horror” and “Wow” are particularly theatrical. Lionheart is the soundtrack of an unwritten Broadway musical). The dilemmas on the album are primarily visual. Bush envisions not just how inner collapse feels but how it looks.

To Bush, blue is “the color of my room and my mood.” It’s a ubiquitous color for her, present on the walls, in the sky, “out of my mouth” (a possible pun), and “the sort of blue in those eyes you get hung up about,” perhaps an allusion to the ever-growing canon of songs about blue eyes. Bush is making a world of blue, one where external hue, metaphor, and internal state collide in a musical act of mise-en-scène. “Symphony in Blue” is a dive into introspection wherein the act of introspection becomes the entirety of Bush’s world. Bush’s fixation on blue largely rises from dissatisfaction, remaining in a state where all you can grasp is the banal details of your immediate environment.

The second half of the first verse fixates on the thoughts that arise when “that feeling of meaninglessness sets in,” ones that pertain to “blowing my mind on God.” This part of the verse is mostly a list of idioms describing God, from the basically metaphorical (“the light in the dark”) to the scriptural (“the meek He seeks/the beast He calms”) to the bureaucratic (“the head of the good soul department”). Bush’s God always occupies the role of the enigmatic man in Bush’s songs, more an amalgam of resonances and qualities than an identifiable person. He is a presence, but a largely offstage one used by Bush to hurl her anxieties at.

In its second verse, “Symphony” explores red, a more fatal, dramatic, and alarming color than blue. “I associate love with red/the color of my heart when she’s dead.” Bush invokes a sense of viscera, with thoughts of death coming to mind as she ruminates in her room. For a second it looks like she might not survive the song. The rest of the verse is more straightforwardly physical, with Bush delivering the astonishing line “the more I think about sex, the better it gets.” As the song navigates its way out of emotional traps by listing potentials ways out, sex is inevitably going to come up.

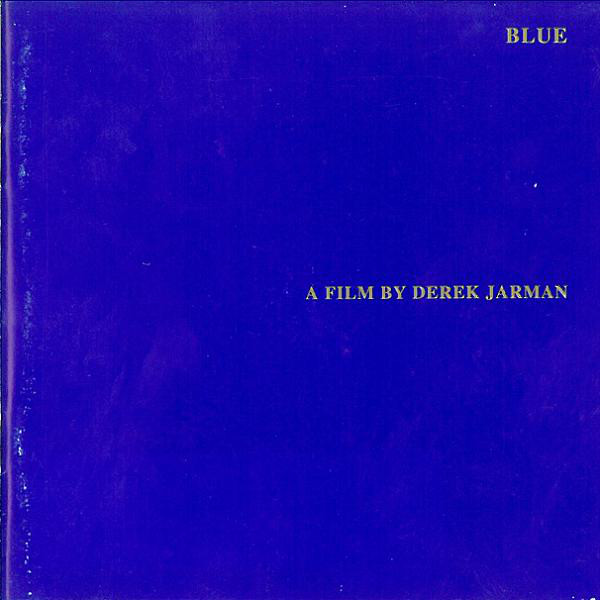

The best way for Bush to articulate her ennui is visually: she will compare her mood to something visible. Blue is of course the color of many songs — in many ways, it’s the most musical color. One of the foundational genres of popular music is the blues. Blue is used as a synonym for sadness, a catalyst for innumerable amounts of music. Lord knows there’s no shortage of songs about blue — an even slightly comprehensive list would take up several blog posts. “Symphony in Blue” obviously apes its title from Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue,” yet kicks things up a notch by moving the color up from a mere rhapsody to a whole symphony. Perhaps the most relevant song to “Symphony in Blue” for our purposes is David Bowie’s contemporaneous and relatively similar “Sound and Vision.” From its title to its repetition of “blue, blue, electric blue,” the songs are similar in a way that’s difficult to nail down as a total coincidence (although it is entirely possible Bowie’s influence on Bush in this case was subconscious). Both use the surroundings of blue rooms as reflections of internal dissatisfaction. Crucially, both songs unify sight and sound into a single phenomenon. Bush’s chorus begins with “I see myself suddenly on the piano as a melody,” wherein melody is both a reflection of self and a visual reflection. Bush’s favorite theme of music’s tangibility has reached its apotheosis. Lionheart is paying off a debt to The Kick Inside via one of its fullest realizations of its ideas.

Musically, “Symphony in Blue” references more artists than just 20th century ones such as Gershwin and Bowie. The song deliberately gestures at 19th century French composer Erik Satie’s most famous piano compositions, the Gymnopédies. Like “Symphony in Blue,” Gymnopédie No. 1 is in ¾ and begins with a G major 7th chord. Both pieces are airy and chromatic (a trend in 19th century music to be found in the work of, for example, Debussy, another favorite composer of Bush’s), and Bush’s drifts slowly through G major, often falling onto 7th chords or flattening 6ths. There’s a jazz-influenced airiness to “Symphony” which is also inherited from the Gymnopédies and is clearly evidenced by its use of F7sus4, a true mind-fuck of a chord. The resemblance is intentional — “Symphony in Blue” is a pop song, as its reliance on Iain Bairnson’s electric guitar demonstrates, but it’s outright smuggling classical music into the charts. In Bush’s Christmas special, she begins “Symphony in Blue” by playing Gymnopédie No. 1, dutifully playing the song in G before pivoting on a D minor chord to “Symphony.” Bush is playing the cultural creator, collecting influences and displaying them for posterity. When she draws on tradition, it’s not merely to recreate visions of the past, but to find new directions for preexisting ideas. Bush spends a lot of her time looking at blue, so there was no chance she’d blue it.

Recorded July-September 1978 at Super Bear Studios in Nice. Released as lead track of Lionheart on 12 November 1978; released as third single of said album on 1 June 1979. Played live on Tour of Life. Personnel: Kate Bush — vocals, piano. Stuart Elliott — drums. Iain Bairnson — electric guitars. David Paton — bass. Duncan Mackay — Fender Rhodes.