The Sentinels Lied About All Them Space Wars (The Last War in Albion Part 29: Alan Moore’s First Future Shocks)

This is the fifth of ten parts of Chapter Five of The Last War in Albion, covering Alan Moore’s work on Future Shocks for 2000 AD from 1980 to 1983. An ebook omnibus of all ten parts, sans images, is available in ebook form from Amazon, Amazon UK, and Smashwords for $2.99. If you enjoy the project, please consider buying a copy of the omnibus to help ensure its continuation

Most of the comics discussed in this chapter are collected in The Complete Alan Moore Future Shocks.

Most of the comics discussed in this chapter are collected in The Complete Alan Moore Future Shocks.

PREVIOUSLY IN THE LAST WAR IN ALBION: Alan Moore’s first few short stories for 2000 AD focused mainly on robots, but gave him his first opportunity to work with Dave Gibbons…

You’re saying the Sentinels lied about all them space wars? Well what have they been doin’ all these years? – Alan Moore, Top Ten #12

These strips culminate in “The Wild Frontier,” a story that demonstrates straightforwardly how Gibbons’s art style lends itself to Moore’s style of comedy. Moore describes the strip as “one of those stupid things you do when you hear that Dave Gibbons will be drawing a job.” “The Wild Frontier” is a two-page bit of larking about on the premise of a space-western, complete with jokes about “the octobanndits led by that cephalopod sidewinder… Billy the Squid!” and the Clone Ranger, a vast stampede of identical masked men with their catchphrase of “Hiyoo, Chromium! Hawaay!” All of this is depicted by Gibbons in comically ludicrous detail that not only emphasizes the ridiculousness of the concept but wallows in its glorious excess, encouraging readers to dwell on panels to catch all of the sight gags Gibbons has managed to cram in. But even as early as “The Dating Game” Gibbons was showing his propensity for detail, making sure to put the bouquet of Saturnian Singing Orchids that the computer gives Myron in as many panels as possible (and allowing Moore to create more deliciously awful plant rhymes such as “Who cares if the greenfly bite? / I’ve got you to hold me tight. / You’re my man, I don’t mean maybe… / You’re my fertilizer baby.”) and, of course, depicting the sublime lunacy of Myron’s homicidal toothbrush.

|

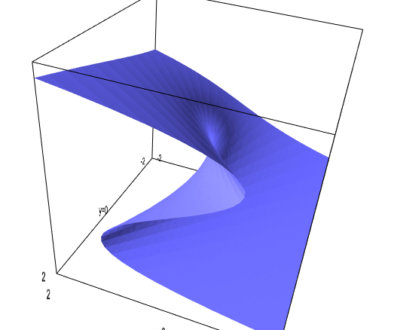

| Figure 219: Alan Moore has admitted that he designed Snazz’s visual appearance in part because it was unnerving and slightly headache-inducing to look at. |

Unfortunately, for all that Moore was clearly better at them than other writers, there simply weren’t a ton of slots for short stories at this period in the magazine’s history. Tharg’s Future Shocks hadn’t appeared since Prog 135 in late 1979, and wouldn’t make a return until March of 1981, at which point Moore began getting published in 2000 AD with considerably more regularity. If his earliest 1980 shorts were merely competent, his 1981 work must be recognized as an extraordinary run of stories. Properly, his hot streak began in December of 1980 with the publication of “Final Solution,” the first of his six stories featuring Abelard Snazz, a genius known for his “two-storey brain” whose schemes inevitably end in humorous catastrophe. This was followed by a run of six consecutive Future Shocks interspersed with two more Snazz stories that constitute the most sustained run of quality and creativity that the Future Shocks line ever had.

The claim that Future Shocks trade on twist endings is often repeated, and it’s certainly true that they appear a lot, in Moore’s best work the twist ending serves only to provide a narrative resolution to a story that is otherwise about exploring other ideas. For a short story of only four or five pages a twist ending is a natural fit – the length is almost exactly long enough to reasonably develop an idea, but not really long enough to develop a second one. And so the natural structure is to develop the idea, take it in a surprising direction, and then stop without having to worry about the consequences of that change. Often this is the point of the exercise – there’s few ways to explain “A Holiday in Hell,” for instance, except in terms of its final revelation. But other times the twist ending is just a frame to hold a different sort of story.

| Figure 220: The Grawks, designed as parodies of Australian tourists, step out of their spaceship (“Grawks Bearing Gifts,” written by Alan Moore, art by Ian Gibson [as Q. Twerk], 2000 AD #203, 1981) |

“Grawks Bearing Gifts,” the first of Moore’s stories to actually bear the Tharg’s Future Shocks label, is a prime example. The story has a a twist ending, to be sure, but the twist comes halfway down the penultimate page. The ending panel is still there for a comedic punchline, but it’s not a plot twist in the least. The basic form of a twist ending is still there – several pages of fleshing out an idea only to reveal a key detail about the idea that casts everything in a new light. But the story isn’t built to emphasize that. Instead the point of the story is the nature of the twist. The story concerns a race of aliens called the Grawks (which Moore impishly notes are depicted via “a lot of terrible racist slurs directed at Australians” and offers “no defense for this, and, in the tradition of Conservative cabinet-ministers when asked why they were card-carrying members of the National Front until three weeks previously,” declares that he will “put it down to the indiscretions of a reckless youth.”) who arrive on Earth and act like stereotypical dumb tourists, in particular freely handing out large amounts of gold for the privilege of buying various major landmarks. Until, on the fourth page, the Grawks produce a page of trans-galactic law that explains that “purchase of properties on all planets shall be considered binding if the seller and signatory is a bona-fide member of the planet in question” and that “ignorance of this clause may not be deemed an excuse.” Having acquired the entirety of the planet and collapsed the economy by flooding it with gold, they proceed to rename the planet, rework various landmarks in their own image, and shove the human population into reservations, leading to a final panel of Margaret Thatcher consoling a broken-hearted general who failed to plan for this eventuality while a Grawk standing outside the sign saying “Earthling Resettlement Area No. 2085” snaps a picture and happily exclaims, “coo-eeee!”

With the twist coming comparatively early in the story and without any real suddenness (page three is already mostly about the degree to which Grawks are taking over things), the story stops being about the cleverness and starts being about the nature of what the Grawks are doing. The twist is a means to an end, that end being a story that takes a variety of things Europeans, and particularly the British, have done to any number of cultures over the years. The point of the story is to show Britain (and the world at large, though notably Moore only depicts European and American areas being taken over by Grawks) on the receiving end of treatment it has historically dished out. The twist isn’t a surprise, but rather a tool for Moore to engage in scathing cultural commentary.

| Figure 221: The vacation from hell (“The English/Phlondrutian Phrasebook,” 2000 AD #214, 1981) |

Moore’s next Future Shock, “The English/Phlondrutian Phrasebook,” challenges the usual plot structure of a Future Shock even further – enough so, in fact, that it went out without any sort of banner. The story is presented as a found object – each page contains an image of a “Vocosonics Futura Transliterator” that is presenting the eponymous phrasebook (one of the characters can be seen to be holding the device in several of Brendan McCarthy’s delightfully barmy images). The story consists of a series of helpful Phlondrutian phrases for a potential traveller, divided into sections like “At the Spaceport,” “At the Hotel,” “On the Beach,” and, later, “While Being Arrested” and “On the Slave Satellite.” The plot, then, exists as an implication – the images depict one hapless pair of tourists as they go through the nightmarish vacation suggested by that progression of sections, but the story is not so much about one specific Kafka-esque vacation so much as it is about the underlying joke of a planet where “waiter, my soup is giggling” and “sign a confession? But we are innocent!” are both essential phrases for the prospective traveller. The strip is an experiment in style and technique – an attempt to see how changing the underlying structure of a narrative changes the stories that can be told. This sort of careful focus on structure and particularly on structural experimentation will go on to become on of the most fundamental techniques in Moore’s repertoire.

This is not to suggest, however, that Moore avoided the straightforward twist ending story entirely. “The Regrettable Ruse of Rocket Redglare,” for instance, plays its twist ending very straight. The story shows Rocket Redglare, a Flash Gordon-style hero who’s well over the hill, and is first shown struggling to lace his middle-aged flab into a corset so he can don the old costume to pen a Mega-Market. Desperate to prove his relevance, he contacts his old arch-foe Lumis Logar, and proposes that Logar fake an invasion of Earth for Redglare to repel, thus restoring his faded glory. Logar accepts the proposal cheerily, asking rhetorically, “who could bear a grudge for thirty years?” The answer, as revealed in the final panel, is that he could, as he ends up launching a real invasion and casually killing off Redglare.

|

| Figure 222: Rocket Redglare is not the lithe action hero he used to be. (“The Regrettable Ruse of Rocket Redglare,” written by Alan Moore, art by Mike White, from 2000 AD #234,1981) |

The story recognizably employs one of Moore’s standard techniques – the reconsideration of an existing pulp narrative from a quasi-realist perspective, usually one that assumes the passage of time. He’ll go on, of course, to use the same basic premise to vast critical acclaim on both Marvelman and Watchmen. The “quasi” here is, in fact, important. There is little that is actually realistic about “Rocket Redglare.” The idea that Redglare’s nemesis needed Rocket’s regrettable ruse in order to launch his revenge holds up to barely any scrutiny, and the world of the story strikes a compelling but fundamentally preposterous balance between treating Redglare and Logar as actual people in a world and treating them as fictional characters. It’s telling that Redglare’s scheme is not one to make money, but rather one to regain his popularity. His problem, in other words, is one faced as a fictional character – he’s declined in popularity and has been cancelled, in effect. His financial success comes the same way any franchise does – toys, t-shirts, bubblegum cards, and films. His marriage, tellingly, was fixed up by his and his wife’s mutual agent. He is, in effect, an actor whose movie franchise has stalled, but where his movie franchise also has potentially deadly real-world implications. The point is not a gritty, realist “let’s pretend these fictional characters existed in the real world,” but rather a riff on what would happen if a single real-world concept – the sense of being over the hill – were imported into a fictional setting. Within that, it uses another classic and well worn plot structure: the con man whose unethical scheme blows up in his face.

|

| Figure 223: It is relatively easy to figure out which collection of Spinrad stories contains “The Last Hurrah of the Golden Horde.” |

“The Last Rumble of the Platinum Horde,” is a similarly basic twist-ending story in which the Karbongian Empire, lacking anyone left to conquer, sends out its last great army, the Platinum Horde, to sweep across the universe until they reach the edge of space itself. Space turns out to be curved, however, and after generations of slaughter the Platinum Horde circles back on the decaying remains of the Karbongian Empire itself, the all-conquering serpent biting down hard upon its own tail. Moore, in his typically self-depricating manner, notes that he’d “like to claim that it was a bitter and satirical attack upon the mindless brutalities of war,” but that “it was really just plain bloody violent,” laying most of the praise at the feet of John Higgins, who he claims “did a stirling job in depicting the lighter side of genocide.” (Moore also notes that since writing the story he’s discovered that the title “was partially stolen from a Norman Spinrad story which, if you can find it, is much better than this one. The story in question, “The Last Hurrah of the Golden Horde,” makes an interesting counterpoint to Moore’s.

Spinrad’s story features the character of Jerry Cornelius, created by Michael Moorcock [whose New Worlds published Spinrad’s novel Bug Jack Barron when other publishers wouldn’t touch it, which resulted in New Worlds taking heat in the House of Commons due to its partial funding from the British Arts Council] being dragged into a convoluted web of double crosses and intrigue in Maoist China, which he resolves by using a specially made violin to induce a massive outbreak of violence, resulting in a scene whereby “Major Sung shrieked: ‘Capitalistic running dogs of the demographic People’s revisionist lackeys of Elvis Presley have over-run the ideological manifestations of decadent elements within the amplifier of the pagoda!’ and committed hari-kiri” while “The Rock began smashing slot machines with a baseball bat” and “Starlets tore off their bikinis and chased terrified hatchet men around the poolside” as “The Human Wave reached the pool, dove in, and proceeded to beat moribund crocodiles to death with their gunbutts” alongside “A suicide squad” that “hurled itself through the plate glass window of a trailer and devoured the rug” while simultaneously “Cadillacs circled the boxcar of heroin like hostile Indians, filling the air with hot lead” contemporaneously with the moment “The sopping remnants of the human wave reached the trailer camp and began beating thugs to death with dead crocodiles” synchronized with the point when “Red Guards showered the C-5A with ink bottles” concomitantly with the moment “Tongues of flame were everywhere” and “Explosions, contusions, fire, gore, curses, looting, rape,” all of which, in the original manuscript, are treated as distinct paragraphs.

|

| Figure 224: Jerry Cornelius, as drawn by frequent 2000 AD contributor Kevin O’Neil. |

This cacophony of violence is finally stumbled upon by the “two hundred decrepit remnants of what had once been the glorious Golden Horde, most of them incoherent with exhaustion.” The horde, who, in addition to being in the title, have lurked in the background of the story, with occasional paragraphs describing their slow and pathetic march charge gamely into the combat only to discover “to their chagrin that there was precious little unburnt, unpillaged, unraped, unkilled” and all dying pathetically. The story ends with Cornelius attempting to ride off on the horse of the last Khan of the Golden Horde, which is said to have “waddled forward a few steps, puked, and died.” And that’s basically that. [continued]

January 30, 2014 @ 8:03 am

I was wondering when we would bump into Jerry Cornelius again.

January 30, 2014 @ 9:12 am

Of course, in addition to British people finding Australian tourists even more annoying than American ones, referencing white Australians, even as stereotype, adds an extra irony to the imperial colonisation metaphor. (On a more trivial note, I love the detail that Mrs Grawk's camera is built into her Dame Edna specs.)

Typo alert: I think Rocket Redglare intends to open a Mega Market, not pen one.

January 30, 2014 @ 11:01 am

Snazz's visual design really is quite disconcerting, my brain wants to force the two pairs of eyes together.