Eruditorum Presscast: The Witchfinders

Join El and Annie Fish (whose delightful Patreon is here) for a discussion that is at times about The Witchfinders. Listen here.…

Join El and Annie Fish (whose delightful Patreon is here) for a discussion that is at times about The Witchfinders. Listen here.…

Join El and Annie Fish (whose delightful Patreon is here) for a discussion that is at times about The Witchfinders. Listen here.…

Join El and Annie Fish (whose delightful Patreon is here) for a discussion that is at times about The Witchfinders. Listen here.…

The cynical account would be that this avoided endorsing the idea that witch hunters had some valid points, and so is within the context of the Chibnall era borders on being a triumph. The more considered account would be that this retains many of the Chibnall era’s most annoying tics, but generally de-emphasizes them while succeeding at finding some new spins on old standards, which is to say that it works out more or less like the best case for the era.

At its heart it offers “what if spooky Doctor Who but with Alan Cumming camping it up throughout. The flaw here is that there’s not really a reason for these things to combine; King James’s arrival is only vaguely motivated and the plot really doesn’t particularly need him. His only role seems to be to keep the script from just being a kind of dreary mud zombies story. But while there’s a sloppiness to how Cumming is worked into the episode, he’s blatantly the best thing about it. Doctor Who works off of contrasts, and the gloomy folk horror of the plot along with Cumming’s wanton consumption of the scenery is an effective one. That it’s thinly justified isn’t a huge issue; something is always thinly justified in a fifty minute episode.

More to the point, the mud zombies kinda needed the help. They’re not bad, but it’s telling that their name, history, and plan are introduced and then dealt with inside of the last ten minutes, and that this, while slightly jarring, does not really feel like it detracts from them. They’re very “standard Doctor Who stuff,” and their abrupt reversion from spooky atmospherics to a completely standard explanation for this sort of thing is fine so long as they’re functioning as a platform for other things to happen. So the story needs a King James of some sort.

Thankfully, the King James it goes with is delightful. Doctor Who fans have, of course, known that Alan Cumming fits well with Doctor Who stuff since 1993, but at last we have him in the series proper. But he’s bolstered by the bold decision to have King James be, to put it bluntly, fucking terrible. The ideology of hero worship is probably the biggest of the millstones around the celebrity historical, and throwing the Doctor with a historical figure who’s revealed to be a complete shit is tremendously refreshing. Cumming, meanwhile, is capable of taking a character whose every trait is negative and making him entertaining without any redemption arc whatsoever. An episode built entirely around him would probably be annoying, but balancing him with mud zombies is exactly the sort of contrast that makes good Doctor Who, and ultimately if you stick the result you can handwave the setup.

This also marks the first time anyone has thought to handle Jodie Whittaker by giving her a talented co-star and letting her have a bunch of big scenes with them. While still waiting for an iconic hero moment, the exchange with King James when she’s tied up is easily her best scene this season, followed, really, by the scene of her about to be drowned.…

I’m pleased to announce that I’ve set up an Eruditorum Press Discord server. If you’re not familiar with Discord, it’s a chat app originally designed for use by gamers, but that has spread to all sorts of uses and is apparently the hot thing with The Kids These Days. So if you’d like a place to discuss The Witchfinders before my review goes up later in the week, or just a place to hang out and talk about any number of topics with a pretty cool community, you can join the server via this link,

If you’ve never used Discord before, you’ll want to download the program itself first.

Enjoy.…

This week I’m joined by Deb Stanish of the Verity! podcast and Mad Norwegian’s delightful anthology Chicks Unravel Time to talk about the stunning mess that is Kerblam! Because obviously she’s just your go-to person for things with exclamation points in them.

As noted last time, through its strategy – deliberate or not – of eloquent silence, ‘Demons of the Punjab’ almost says that Partition represents the British in India killing millions. It establishes that the British are the ones drawing lines and then running away. Later, the Thijarians say “Millions will die.” The episode aligns the parts of a statement… but never quite joins them up.

As noted last time, through its strategy – deliberate or not – of eloquent silence, ‘Demons of the Punjab’ almost says that Partition represents the British in India killing millions. It establishes that the British are the ones drawing lines and then running away. Later, the Thijarians say “Millions will die.” The episode aligns the parts of a statement… but never quite joins them up.

In a way this is fair enough, since the statement it never quite makes is both true and an oversimplification. Like many simple truths, it is one important part of a complex reality. It is true that the British authorities didn’t mean to cause the horrors of Partition, didn’t themselves take part in the atrocities, and didn’t foresee them. It is true that most of the violence was committed by Indians attacking other Indians. It is true that there has been – both before and after Partition – plenty of violence between Hindus, Muslims, and the other ethnicities in India. It is true that intractable political arguments and gameplay between the Indian parties – mainly Congress and the Muslim League – helped stymie British attempts to avoid Partition. It is true that the Muslims had real and understandable concerns about their future in a Hindu-dominated independent India, not least because of fascistic Hindu movements, with which some upper-caste Hindus in the nationalist movement had ties. Such fascistic elements were involved in organising the violence of Partition as we saw last time.

(Sadly, India today is still cursed with such things. India’s current Prime Minister, Modi, is the authoritarian leader of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), a right-wing Hindu nationalist party, and a member of the BJP’s ‘core cadre’, the right-wing paramilitary Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). There are terrifying concerns about the rise of state-sponsored, racist, right-wing authoritarianism in India today that most of us here in the West have, with Eurocentric purblindness, failed to pay enough attention to as we gaze with horror at our domestic monsters as if they’re the only ones that matter. For more about the RSS, their foundational role in Modi’s politics, their involvement in the violence of Partition, and their connections to Congress, please see here. I’m indebted for this link, and for other suggestions, to TobermorianSass via the ever-wonderful Sam Keeper.)

All that being said, it is also the case that the explosion of violence and displacement in Partition was foreseeable, and that the inevitability was there for the British to see and understand, had they only cared to do so, or ever bothered to install a proper government in India, as opposed to a vast system of bureaucracy designed to give lucrative careers to English public school boys. Mountbatten – a well-meaning but vain and ostentatious man who made a fetish of decisiveness – recklessly brought forward the date of Partition by about ten months so that it would happen on the anniversary of him accepting the surrender of Japanese forces in Asia. Even so, the timetable he was given was already rushed.…

Here’s Part 2 (well, part “2c”) of Ben Knaak’s Alternate Histories project exploring how to model a materialist conception of history through video games. Be sure to follow along on his blog and YouTube Channel!

It is on its face absurd that the crisis over the Panama Canal Company could by itself lead to the largest and bloodiest war the world had ever known. That the two-headed monster of Boulanger and Déroulède would make their usual hash of things was no surprise. That the Panama Scandals would bring about the peaceful downfall of a government which, after regaining Alsace-Lorraine, had no further reason to exist, might have been predicted. That the departure of the pro-British Boulangists, combined with the refusal of the Colombian parliament to approve the sale of the canal concession to Britain, would pit France against her traditional enemy is perhaps understandable. The American invocation of the Monroe Doctrine is practically reflexive. But without recourse to other causes, Britain’s insistence on backing the cause of Panamanian separatism to the point of worldwide destruction makes absolutely no sense.

It is to this end that we must go back to the beginning of this work. Every aspect of the global stage must be understood in terms of the Great Russo-Turkish War of 1873, which brought a decisive answer to the Eastern Question and an even more decisive end to the last traces of the Congress of Vienna. The nationalist movements of the Balkans seemed now to be resolved. Russia had gained the independent allies it sought in the region. Constantinople was now Tsargrad. With the Tsar’s greatest ambitions achieved at a relatively low cost, the time seemed right for peace and rapprochement between the Great Powers.

For a time, it must have seemed that such a state of affairs would endure. Britain and Russia would sign a treaty of mutual defense. Though this closeness lessened after the Russian Revolution of 1884, there would be peace among the Great Powers for more than twenty years. But already the groundwork for the next war was being laid, and the three central questions that turned the Panama Crisis into the Great War were now being raised.

The first of these questions stems from the ethnic and border conflicts which arose immediately among the newly-minted Balkan states. We might call this the Balkan Question, or (following Hobsbawm) the Second Eastern Question. It may be simply stated as follows: How shall the ethnic and national lines of the new Balkan nations be drawn, and where shall the demarcation line between Russian and Habsburg domination be drawn?

The subset of the Balkan Question that raised itself most quickly was the border in Thrace. The Greeks quickly realized that Russian demands for an allied port on the Mediterranean would lead them to back Bulgarian claims to Thrace and Macedonia over their own. They would throw their hats in with the British, even forming a short-lived alliance with the Turkish Republic, in multiple failed attempts to seize Thessaloniki.…

Back in my TARDIS Eruditorum post on The Caretaker, I mused on what Gareth Roberts might have written if he’d been allowed to write Doctor Who that reflected his politics of English middle class supremacism as opposed to being constantly pigeonholed into writing comedy romps, suggesting this would have been preferable and interesting. With Kerblam! we finally test that, and the results are as fascinating and infuriating as you’d expect.

On one level, this is the biggest political fuckup of an episode in recent memory. I mean, it’s a satire of Amazon that comes down firmly on the side of Amazon. It’s consciously pitched as a critique of labor activists in favor of exploitative corporations—one that is overtly hostile to younger generations and that treats concerns about the effects of automation on individual workers as contemptuous. It is overtly in favor of of corporations that aggressively micromanage workers’ exploitation in favor of efficiency, of bullying and abusive bosses, and of automated systems that kill people to make a point. It’s like the Cartmel and Davies eras as rewritten by Nick Land.

The thing is, that’s actually a hell of a pitch. And the first part of it is key—this episode is technically steeped in what made those eras work. It’s full of good ideas that are intelligently put together. Warehouses are a brilliantly achievable setting for Doctor Who. The Kerblam! bots are a delightful mix of creepy and charming. It does a great job of satisfyingly leaning on Doctor Who tropes while still feeling fresh and weird. And I mean, it has killer bubble wrap. I’m ridiculously and overwhelmingly there for killer bubble wrap. The mixture of bright and colorful with spookiness and action sequences is a balance that almost always works for Doctor Who, and it works here. And, in common with scripts that haven’t had Chibnall’s name on them, there’s a sense of focus to this. It knows what it’s about and has the intelligence to focus on the theme. Indeed, it even uses its politics to good effect, trusting in the standard morality of Doctor Who to do the work of setting up red herrings without it having to actually comment on anything so that, for instance, the audience is suspicious of Kerblam! because of its labor practices even when the Doctor doesn’t actually say anything about them. It’s a perfectly good episode of Doctor Who that just happens to be, you know… evil.

In terms of judging its quality, that’s easy enough. Contrary to my detractors who accuse me of exclusively judging Doctor Who by its politics, I’ve been consistent in my view that well-done conservative science fiction is worth doing. This qualifies. I am fascinated by its pathologies—by what it does and doesn’t let itself notice about the world it’s set up, and by how it manages to make this completely and utterly fucked ethical and political assessment work in the context of Doctor Who. In one sense, the detail at the end of closing the plant for a month but only giving the workers two week’s pay is as fantastically perverse as the detail of Cordo’s father’s body being worth more than his life savings in The Sunmakers.…

The historian Yasmin Khan, who wrote a book about the Partition of India that Vinay Patel, the writer of ‘Demons of the Punjab’, has tweeted about having read as research, wrote that the Partition is “a history layered with absence and silences”.

The historian Yasmin Khan, who wrote a book about the Partition of India that Vinay Patel, the writer of ‘Demons of the Punjab’, has tweeted about having read as research, wrote that the Partition is “a history layered with absence and silences”.

Yes, her name is Yasmin Khan.

What does that mean? Does it mean anything? We must simply add this to the list of questions ‘Demons of the Punjab’ raises, or almost raises, and then remains silent about.

‘Demons of the Punjab’ is an episode haunted by silences. Pregnant, eloquent silences. I don’t know if this is deliberate, in the sense of being a conscious strategy on the part of the people who made it. Whether this matters is itself a question to consider.

The first pregnant, eloquent silence comes very near the start, when the elderly Umbreen remarks that she was “the first Muslim woman to work in a textile mill in South Yorkshire”. This follows her remark, itself news to Yaz, that she was the first woman married in Pakistan. Umbreen has been very silent for a long time.

Contrary to myth and apologia, India before the British came was a wealthy, thriving country. According to Shashi Tharoor in his book Inglorious Empire, “At the beginning of the eighteenth century, as the British economic historian Angus Maddison has demonstrated, India’s share of the world economy was 23 per cent, as large as all of Europe put together”.

As he goes on to say:

Britain’s Industrial Revolution was built on the destruction of India’s thriving manufacturing industries. Textiles were an emblematic case in point: the British systematically set about destroying India’s textile manufacturing and exports, substituting Indian textiles by British ones manufactured in England. Ironically, the British used Indian raw material and exported the finished products back to India and the rest of the world, the industrial equivalent of adding insult to injury.

The British destruction of textile competition from India led to the first great deindustrialization of the modern world.

It is tempting to quote Tharoor’s devastating description of the cynical and violent methods by which this was achieved at length… but it would be hard to know where to begin or stop. People who want the grisly details can read his book. (I highly recommend it. I have nitpicks with Tharoor, but overall his book is a brilliant and accessible introduction to the forgotten horrors of the British Empire in India, as well as a demolition of the more popular apologias.)

Britain’s industrial revolution was funded by the deindustrialisation of India, and textiles were a big part of how and why it worked. (As we know, the British textile business was also dependant upon cotton produced by slaves in the Americas.)

By the way, another industry at which the pre-colonial Indians excelled as steel production. The British hijacked that too, having destroyed the Indian industry. Sheffield became best known as a British centre of steel production, becoming known as ‘the steel city’. Lest we imagine that ‘the British’ benefited from this as an abstract category, it’s worth remembering how “extraordinarily injurious” the work of being a steel-grinder in the Sheffield cutlery industry was, as Engels put it in his 1844 book The Condition of the Working Class in England.…

We here at Eruditorum Press are unrepentant SJWs, and so we care about diversity. Accordingly, we decided it wouldn’t do to have an entirely homogenous lineup of podcast guests, and so have made a token diversity hire this week to bring you an actual cishet male to comment on Doctor Who. We would like to assure you that Jack was hired with no consideration whatsoever to his merits, and his entire existence is simply an act of crass virtue signalling.

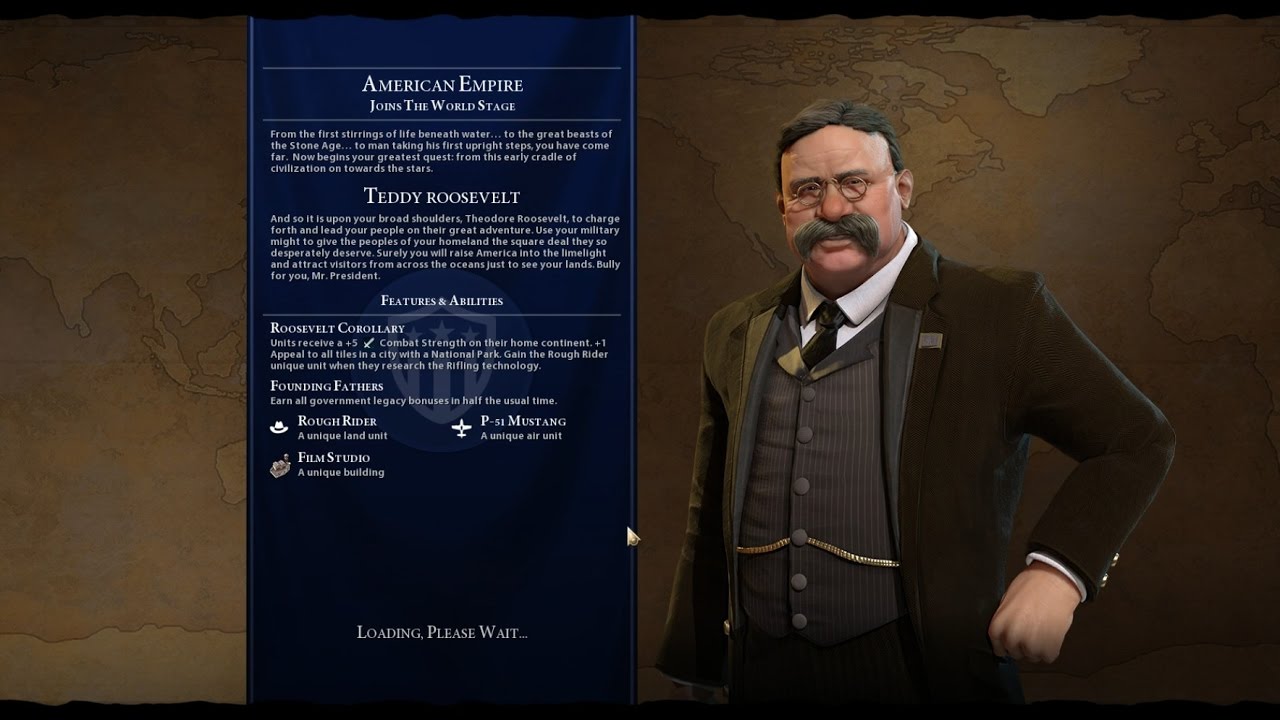

Here’s Part 2 (well, part “2b”) of Ben Knaak’s Alternate Histories project exploring how to model a materialist conception of history through video games. Be sure to follow along on his blog and YouTube Channel!

In most 4X games in which the player controls a nation, that nation’s identity, attributes, and associated play style remain static and constant. Rather than a contingent cultural and political reality that arises from particular circumstances, the nation is an eternal reality. It will often have a set of statistical bonuses or accompanying debuffs, or a unique unit or building it can construct once the correct technology has been researched, simply by virtue of being itself. The nation exists at the beginning of the game, and barring conquest by another nation it will exist at the end. Every player who chooses “America” begins history with the founding of Washington in the year 4000 B.C. Where did these people come from? Are they white? Patawomeck? Who is this Washington they named their settlement after? It’s not important; welcome to the United Neolithic States.

This works fine for a Civilization game, but for grand strategy, it just won’t do. And it especially won’t do for a game like Victoria II, which attempts to draw from a more sophisticated, materialist version of Video Game History™. This is a game in which the names, flags, and borders of its states must necessarily change with astonishing regularity, and in ways that are historically contingent without being pre-ordained. Prussia, or perhaps Austria, becomes Germany. Sardinia-Piedmont, or perhaps the Two Sicilies, or perhaps the Papal States, becomes Italy. Or perhaps neither of those states comes into being. New countries are carved from the carcasses of moribund empires, imposed from without and from within.

What, then, are the in-game forces that govern these processes? As you would expect, nationalist movements are partially determined by the POP system. Every POP group has an associated culture group. In Ethiopia, for instance, one might have a POP group of Oromo craftsmen working with a group of Tigrayan clerks in a factory owned by Amhara capitalists. Each country, in turn, has at least one culture designated as its primary culture, and may have one or more accepted cultures. Status in one of these groups has a significant effect on POPs’ beliefs and behaviors. Primary culture POPs are more likely to support residency for non-primary culture POPs, while accepted culture POPs are more likely to support limited citizenship (which, for instance, allows accepted culture POPs to vote if your country allows elections). Primary culture POPs are also much more likely to promote to capitalists and other upper-class strata. Non-accepted POPs with high literacy, good living conditions, and few reasons to complain will tend to assimilate to an accepted culture, unless there exists a nation with their culture as its primary culture which holds cores on that province. Meanwhile, literate, high-consciousness POPs of a non-accepted culture are likely to see their militancy increase if their rights are not granted.…