Guest Post: Alternate Histories, Part 2c: No, Really, I’m Just Making This Up As I Go

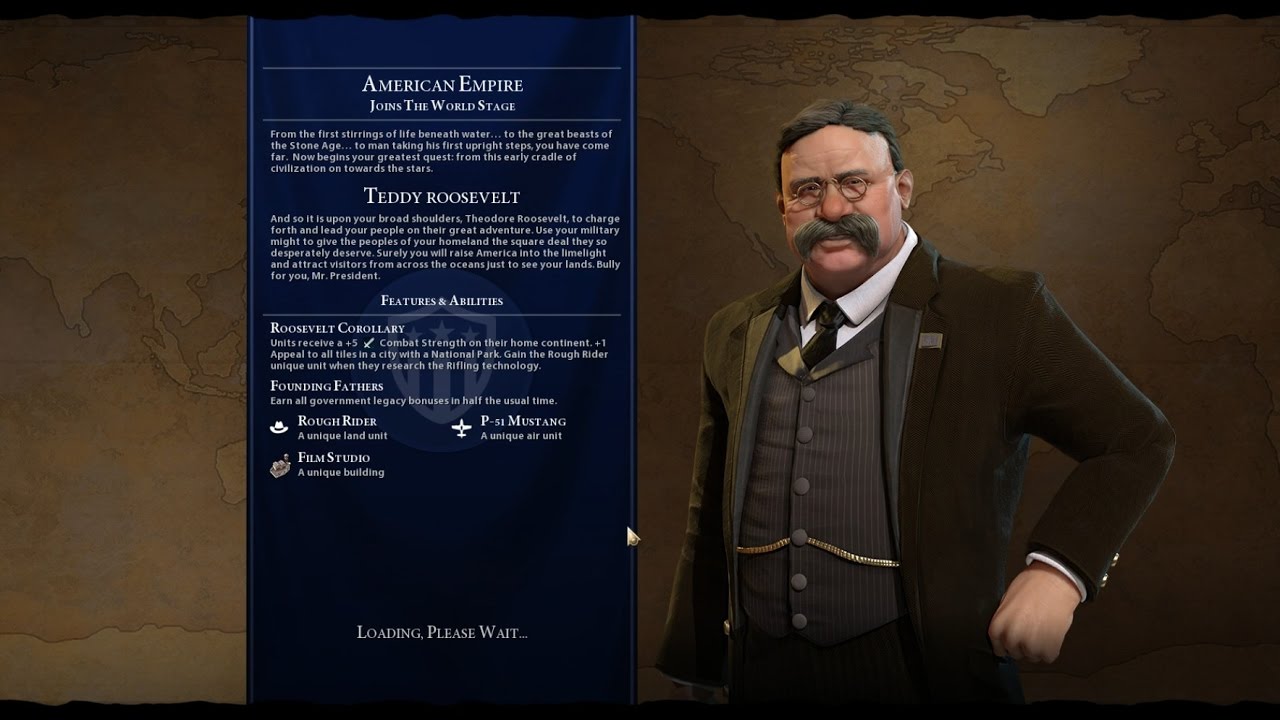

Here’s Part 2 (well, part “2c”) of Ben Knaak’s Alternate Histories project exploring how to model a materialist conception of history through video games. Be sure to follow along on his blog and YouTube Channel!

Shit I Don’t Really Know, But Can Fake, Part I: How’s the Game Going?

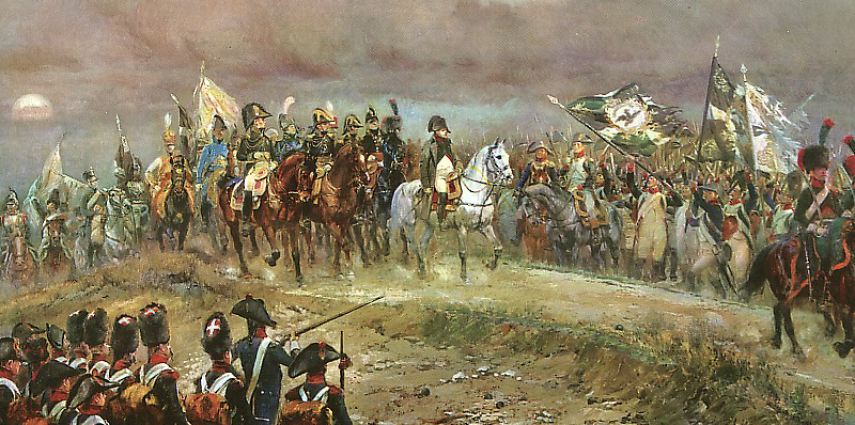

It is on its face absurd that the crisis over the Panama Canal Company could by itself lead to the largest and bloodiest war the world had ever known. That the two-headed monster of Boulanger and Déroulède would make their usual hash of things was no surprise. That the Panama Scandals would bring about the peaceful downfall of a government which, after regaining Alsace-Lorraine, had no further reason to exist, might have been predicted. That the departure of the pro-British Boulangists, combined with the refusal of the Colombian parliament to approve the sale of the canal concession to Britain, would pit France against her traditional enemy is perhaps understandable. The American invocation of the Monroe Doctrine is practically reflexive. But without recourse to other causes, Britain’s insistence on backing the cause of Panamanian separatism to the point of worldwide destruction makes absolutely no sense.

It is to this end that we must go back to the beginning of this work. Every aspect of the global stage must be understood in terms of the Great Russo-Turkish War of 1873, which brought a decisive answer to the Eastern Question and an even more decisive end to the last traces of the Congress of Vienna. The nationalist movements of the Balkans seemed now to be resolved. Russia had gained the independent allies it sought in the region. Constantinople was now Tsargrad. With the Tsar’s greatest ambitions achieved at a relatively low cost, the time seemed right for peace and rapprochement between the Great Powers.

For a time, it must have seemed that such a state of affairs would endure. Britain and Russia would sign a treaty of mutual defense. Though this closeness lessened after the Russian Revolution of 1884, there would be peace among the Great Powers for more than twenty years. But already the groundwork for the next war was being laid, and the three central questions that turned the Panama Crisis into the Great War were now being raised.

The first of these questions stems from the ethnic and border conflicts which arose immediately among the newly-minted Balkan states. We might call this the Balkan Question, or (following Hobsbawm) the Second Eastern Question. It may be simply stated as follows: How shall the ethnic and national lines of the new Balkan nations be drawn, and where shall the demarcation line between Russian and Habsburg domination be drawn?

The subset of the Balkan Question that raised itself most quickly was the border in Thrace. The Greeks quickly realized that Russian demands for an allied port on the Mediterranean would lead them to back Bulgarian claims to Thrace and Macedonia over their own. They would throw their hats in with the British, even forming a short-lived alliance with the Turkish Republic, in multiple failed attempts to seize Thessaloniki.…

The earliest known state to emerge was the Kingdom of D’mt around the 10th century BCE. The people of this kingdom spoke an early Ethio-Semitic language, and traded extensively with the Sabeans of the Southern Arabian peninsula. (They were almost certainly not descended from Sabean migrants themselves – Ethiopia was, in fact, one of the first places Semitic languages were spoken). This kingdom gave way to (or evolved into, or was incorporated into) the Kingdom of Axum, a prosperous superpower whose extent at its apex reached across the Red Sea into Yemen. Notably, it was among the first states to adopt Christianity as an official religion. Axum collapsed under mysterious circumstances in the 10th century CE, even as the heart of its territory remained predominantly Christian. This was succeeded by the Ethiopian Empire, ruled first by the Zagwe dynasty and then by the Solomonic dynasty – so named because it claimed descent from the first King of Axum, whom they claimed was the son of King Solomon by the Queen of Sheba.

The earliest known state to emerge was the Kingdom of D’mt around the 10th century BCE. The people of this kingdom spoke an early Ethio-Semitic language, and traded extensively with the Sabeans of the Southern Arabian peninsula. (They were almost certainly not descended from Sabean migrants themselves – Ethiopia was, in fact, one of the first places Semitic languages were spoken). This kingdom gave way to (or evolved into, or was incorporated into) the Kingdom of Axum, a prosperous superpower whose extent at its apex reached across the Red Sea into Yemen. Notably, it was among the first states to adopt Christianity as an official religion. Axum collapsed under mysterious circumstances in the 10th century CE, even as the heart of its territory remained predominantly Christian. This was succeeded by the Ethiopian Empire, ruled first by the Zagwe dynasty and then by the Solomonic dynasty – so named because it claimed descent from the first King of Axum, whom they claimed was the son of King Solomon by the Queen of Sheba.