A Brief Treatise on the Rules of Thrones 3.03: Walk of Punishment

|

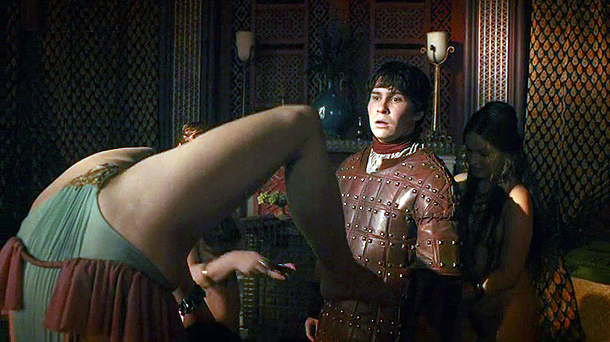

| Daniel Portman perfectly duplicates the reaction of George R.R. Martin’s editors to the Mereneese Knot |

Please enjoy our new and improved captchas while commenting on this article.

State of Play

The choir goes off. The board is laid out thusly:

Lions of King’s Landing: Tyrion Lannister, Cersei Lannister, Tywin Lannister

The Lion, Jaime Lannister

Dragons of Astapor: Khaleesi Daenerys Targaryen

Direwolves of the Wall: Jon Snow

Direwolves of Riverrun: Robb Stark, Catelyn Stark,

Bears of Astapor: Jorah Mormont

Mockingbirds of King’s Landing: Petyr Baelish

Burning Hearts of Dragonstone: Stannis Baratheon, Mellisandre

The Kraken, Theon Greyjoy

Archers of the Wall: Samwell Tarly

The Direwolf, Arya Stark

Tigers of Riverrun: Talia Stark

The Stag, Gendry

Bows of the Wall: Ygritte

Bears of the Wall: Jeor Mormont

Spiders of King’s Landing: Varys

Chains of King’s Landing: Bronn

The Dogs, Sandor Clegane

Winterfell is abandoned and in ruins.

The episode is in ten parts. The first is five minutes long and is set in Riverrun. The opening image is of Hoster Tully’s funeral boat.

The second runs four minutes and is set in King’s Landing. The transition is by dialogue, from Robb talking about Tywin Lannister to Tywin.

The third runs eight minutes and is in sections; it is set in the Riverlands. The first section is two minutes long; the transition is by family, from Cersei, Tyrion, and Tywin to Jaime Lannister. The second section is three minutes long; the transition is by hard cut, from Brienne realizing what she faces to Gendry working on armor. The third section is two minutes long and is set in Riverrun proper; the transition is by family, from Arya to Catelyn Stark. The fourth section is one minute long; the transition is by dialogue, from Catelyn and Brynden talking about Robb to Martin Lannister and Talia talking about him.

The fourth part runs seven minutes and is in sections; it is set north of the Wall. The first section is two minutes long; the transition is by dialogue, from Talia talking about Robb’s supposed powers to the precise butchery of the White Walkers. The second section is four minutes long; the transition is by dialogue, from Mance Rayder talking about the Night’s Watch to the survivors stumbling into Craster’s Keep.

The fifth part runs two minutes and is set in the Dreadfort, though this is not revealed. The transition is by theme, from the monstrosity of Craster to that of Ramsey Snow.

The sixth part runs two minutes and is set in Dragonstone. The transition is by hard cut, from Theon riding off to the shore.

The seventh runs seven minutes and is set in Astapor. The transition is by hard cut, from Melisandre walking away to the Walk of Punishment in Astapor.

The eighth runs seven minutes and is set in King’s Landing. The transition is by image, from Daenerys noting that she and Missandei are not men to a lascivious shot of Rosalyn.

The ninth runs four minutes and is set in the North. The transition is by hard cut, from Poderick to an establishing shot of hills.

The tenth runs six minutes and is set in the Riverlands. The transition is by image, from Ramsey and Theon in a forest to Brienne bound to a tree. The final image is of Jaime screaming as he realizes he has failed to achieve a Full Web (and also had his hand cut off).

Analysis

Unlike “Valar Dohaeris” and “Dark Wings, Dark Words,” “Walk of Punishment” is a basically formless collection of scenes. It’s also a spectacularly good episode. In many regards this demonstrates the season in microcosm; it is an episode largely unconcerned with the business of the macro scale, and that instead gets out of the way of the show’s strengths, which are the intricacies of its small mechanics.

The opening funeral scene is indicative, effectively introducing Edmure and Brynden without even requiring dialogue, and while managing to be bleakly funny to boot. The raw materials of this are all in A Storm of Swords, but the particulars of the arrangement – the decision to use the funeral scene to introduce the two characters, and the distillation of the scene to a simple microcosm of the haughtily incompetent Edmure and the brashly competent Brynden is all the work of the show, and is delightful. And the subsequent scene, fleshing out this relationship in dialogue, is equally deft. Richard Madden is not consistently one of the show’s strongest performers, struggling to imbue his character with a sense of interiority, but his mixture of anger and authority as he delivers Edmure’s dressing down is fantastic and Tobias Menzies’s increasingly inept arrogance is masterfully played.

Similar bits of deftness abound. Emilia Clarke is superlative, making the wise decision not to imbue her negotiations with Kraznys with any sense of doubt or suspense as to whether she is in control of the situation, making the question not “is Daenerys going to get through this OK” but rather “OK, so what’s her plan?” The script pushes in this direction, of course, with her sublime bit of snark to Missandei (“we are not men”) and her icy rebuke to Jorah and Barristan, but it’s an impressive turn, and well-executed on every level. Daenerys opened the first two seasons in a position of extreme weakness, clawing her way towards triumph over their course. And so the calm underplaying of her strength is tremendously compelling; previously this sort of “what is the clever person planning” suspense has been associated with characters like Tywin and Tyrion.

Also notable, not least for the amount of space it’s given, is Hot Pie’s survival. Mass slaughter of characters is of course a key part of the Game of Thrones brand, and so the decision to take a character who is by any standard whatsoever completely disposable and give him an extended scene where the entire point is that he gets a dignified and non-fatal farewell is remarkable. Of particular note is the way that the scene’s comedy is made of small moments that reinforce the small and human scale of the central event, with Joe Dempsie’s delivery of “yes it is” competing fiercely with Maisie Williams’s “it’s really good” for the prize of getting the most depth out of a tiny comic beat.

And of course there are a host of smaller triumphs. Mellisandre’s put-down of Stannis is marvelous, communicating a tremendous amount about Stannis and the way in which his confident authority is, in a fundamental sense, utterly hollow. Daniel Portman’s performance through Poderick’s unexpected emergence as a sex prodigy manages to make what would otherwise threaten to be one of the most grotesquely tawdry uses of sex in the series into a bit of genuine comedy, due largely to the fact that he plays every bit of the scene with the same earnest blankness that he plays everything else, allowing Flynn and Dinklage to sell the comedy with their incredulity. And the final shot, as Jaime’s severed hand, bewildered expression, and scream smash-fades into the rolicking Celtic-punk of The Hold Steady’s rendition of “The Bear and the Maiden Fair,” is perhaps the most wickedly funny instance of the grotesque in the entire series’ history; a case where its inclination to revel in sick and bloody excess is paid off perfectly. (As with the funeral scene at the start, this is a case of savvily reworking the tone of the book.)

But nothing in the episode compares to the chairs scene in the High Council chamber, which exemplifies why the game remains compelling even as its larger machinations go almost entirely off the rails. As with the funeral scene at the episode’s start, it’s a beautiful example of characterization through comedy, although in this case the appeal lies in the way the humor emerges out of well-established characters. What’s great is not simply Cersei’s smirk as she pulls her chair around or the gloriously obnoxious squealing of Tyrion dragging his chair around the table, but the expectant stare of Tywin as he baits his trap, Varys’s raised eyebrows as Littlefinger pushes past him, and, for that matter, the blind and instinctive lunge forward as Littlefinger realizes what’s going on.

At the heart of it is simply the fact that Tywin, Varys, Littlefinger, Cersei, and Tyrion are all well-sketched characters with phenomenal actors who are capable of seizing a small dramatic or comedic moment and making the most of it. And, of course, the same can be said of almost every other great moment in an episode that is absolutely stuffed with them: what makes them good is well-acted characters being given small gems that they polish effectively. The takeaway is clear: for all that the larger business of delivering a dramatically satisfying macro narrative almost completely eludes it, a game whose pieces are this well-worked is almost inherently compelling.

January 25, 2016 @ 12:12 pm

When I first watched it it almost seemed a bit much, following the Riverrun funeral scene so quickly in the same episode with the Small Council chamber scene, just because they use the same, largely wordless comedic style. It felt like they would have been better in separate episodes, but maybe I’m nitpicking.

January 25, 2016 @ 12:12 pm

When I first watched it it almost seemed a bit much, following the Riverrun funeral scene so quickly in the same episode with the Small Council chamber scene, just because they use the same, largely wordless comedic style. It felt like they would have been better in separate episodes, but maybe I’m nitpicking.

January 25, 2016 @ 12:31 pm

Ooops 🙂

January 25, 2016 @ 1:31 pm

Poor Edmure. His boss can’t be bothered to brief him, and somehow that’s his fault. “No, of course you’re not supposed to the fight the enemy when they come at you, and when you are in a position to defeat them – what do you think this is, a war or something? What do you mean, ‘You could have told me’? I was going to tell you, later, once it was too late to make any difference. How could you possibly fail to realise that?!”

It’s absolutely classic crap management behaviour. I realise we’re supposed to be on Robb’s side here, but it’s clearly his incompetence which is chiefly to blame.

It may not be intentional, given that pro-Robb presentation, but it’s a failure that fits interestingly into the whole “never lost a battle but lost the war” thing, since failing to brief subordinates adequately on your plans and approach, so that they either understand exactly what you want or are in a position to make their own decisions on the basis of a reasonable conjecture as to what you probably would want, is on page 1 of How to Lose Wars and Still Be Considered a Military Genius (dumping the blame on those subordinates when things predictably go wrong as a result is on page 2). It’s one of those aspects of leadership whose importance tends to be underestimated when people think of war as a board game between generals, where everyone else is just a piece to be moved around the map (note here Robb’s game-board plotting-table later this season).

It’s part of a linking theme in this episode, since both Daenerys and Ramsay are also engaged in enticing their enemies into a trap while leaving their subordinates in the dark about what they are up to, with uncomfortable results for those subordinates (though we don’t yet get the payoff to the plan in those cases, while Ramsay’s is a rigged, cat-and-mouse game played largely for entertainment rather than a genuine contest, and his henchmen’s role involves suffering worse than a tongue-lashing, but, well, Ramsay).

The comparison between Robb and Daenerys is instructive, helping show why it’s not just accidental that their fortunes are heading in such different directions, and with wider implications about the game. Like Robb, Daenerys tells her lieutenants off for how they react in ignorance of her intentions, but here keeping them out of the loop is clearly a deliberate, calculated choice, and presumably intended to produce just the sort of response it actually does – visible and obviously genuine dismay at her concession, reassuring Kraznys and Co that they are on the right end of this deal. She seems to have accurately thought through how her people are likely to behave if left uninformed and incorporated it into her plans, whereas Robb has blundered into unintended consequences by failing to do so.

Edmure gets chewed out for acting in what is in general a perfectly proper and fairly reasonable way, but with harmful effects in the context of the plan he hasn’t been told about, whereas Jorah and Barristan get it for acting in what is in general a clearly improper, though not unreasonable way, but whose effects are in that context both helpful and presumably planned by their boss. Of course, they could have reacted in a way that was suitably appalled without overstepping the mark by publicly contradicting her, so that exact detail need not have been specifically intended, but either way it works to her further advantage, since it enables her to discipline them on that point in a context where their transgression has actually had beneficial results, rather than waiting for it to happen some other time when it would probably be genuinely harmful.

Well played.

January 25, 2016 @ 6:33 pm

poor Edmure, he rolled a solid 8 on his charisma score. That’s his real problem.

Interesting point about Dany and Rob too

January 25, 2016 @ 9:02 pm

The Captchas are fixed! Hooray!

January 26, 2016 @ 2:02 am

I am always in support of The Chair Agenda.

January 26, 2016 @ 9:31 am

The chair scene is marvellous. But surely in GoT it’s all about the tables. Especially in combination with Lannisters. Two or more Lannisters, a table, and maybe a basic prop or two (a document, a glass of wine, or if the budget’s pinching maybe just a dead stag and some butcher’s knives), and you’re sorted. Guaranteed Lannister Gold.

February 9, 2016 @ 2:57 pm

Love the chair scene.

March 11, 2020 @ 12:55 pm

In the film, she plays a devil from hell to earth to blend into humanity, causing many troubles. Confronted with her is Santa Muerte – the goddess of Latin. I don’t know which side wins.