“A good way to hear God laugh” (David Milch, Deadwood, and Saint Paul)

“I believe one way God says, “I too have a hand here” is in the rhythms and metrics of speech,” writes David Milch, the author of television’s most profane iambic pentameter, in Life’s Work: A Memoir. “[…] The metrics of speech are important and representative of our fellowship even in those of us who feel, mistakenly, that we are separate from each other as individuals.”

That paragraph could well be the perfect synopsis of Milch’s career; fitting enough, as Life’s Work is a self-knowing epilogue — also effectively a last will and testament — to Milch’s corpus. Milch and his family assembled the book through years of dictation by amanuensis as Milch’s Alzheimers has sent him into a decline. Considering that slow process, Life’s Work is stunningly cogent — possibly one of the best I’ve ever read — comparable only to something like Blackstar in its powerful finality.

In essence, Life’s Work is a prayer — like all art is, particularly Milch’s. “Every day, before I write, I pray, and I ask to be willing, and then I see what happens. “I offer myself to Thee to build with me and do with me as Thou wilt. Relieve me of the bondage of self, that I may better do Thy will.” (This is a practice I have started to borrow from Milch — although for him it’s an AA method, whereas I have the curse of alcohol intolerance which prevents me from downing whiskey over a typewriter.) Writing starts with an act of contrition — with utter humility. Art comes from forgiveness.

One gets the impression Milch’s work is fundamentally based in dialogue, not only with God, but with other people (although frankly, that’s not a distinction which has any meaning). Certain truths percolate through the encephalic plaque that accompanies Alzheimers.

“When I look at my grandchildren or I hold them, I can feel that it’s only my individual strength that is subsiding. The strength in the family, in the species, and in the whole beating heart of the universe hasn’t subsided at all.”

Milch’s dedication to the idea of humanity as one contiguous organism comes through even as he gives the impression of being a single-minded solipsist whose drug-and-booze-addled decision-making leads him to do things like sign off part of his ownership in a network TV show to his Vicodin dealer. Or when Milch, as a Yale student, tripping balls on acid, blows out street lights and a police car siren with a shotgun (he then told the cops “I’ll confess when your badge stops melting”). Milch’s account of his addictions, including a gambling penchant which cost his family their financial security, evince a clear sign of an urgent need to fulfill his own desires. His devotion to universalist community is genuine, but it’s clearly tied to his need for gratification.

To call Milch a monomaniac would be problematic given his diagnosed OCD (and learn harder into diagnosis than I’m remotely interested in doing) and yet it’s not exactly wrong. Throughout the book, Milch discusses the need for an “organizing principle” in writing, something around which people can assemble. In NYPD Blue and Deadwood, his two most famous works, characters in hellscapes of endless crises rally around the principle of order. And in all of Milch’s work, language is a tool which we use to wrestle with organization.

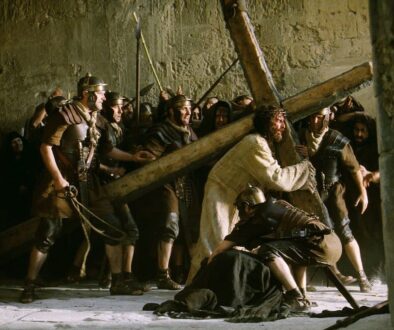

Milch’s long-touted explanation of how this order works, however, doesn’t reflect his writing. As Milch states in Life’s Work (as well as every interview he’s ever done), Deadwood came out of a pitch about Rome where characters rally around Nero or the Cross — the main cast was supposed to be the Urban Guard arresting Saint Paul. When HBO asked him to explore the same themes in a non-Roman setting (due to them already producing Rome), Milch settled on gold as a symbol that people gather around. Some years ago, my mother gave a rejoinder to this point: “The problem should be obvious: gold isn’t a symbol, it’s a commodity.”

Indeed, while gold ultimately draws Deadwood’s characters to the Black Hills, what keeps them there is the mini-civilization of the mining camp. Most of the cast isn’t prospectors or claim seekers. Swearengen profits off the men who pan for gold in the creek. Bullock and Star do the same on a smaller scale while maintaining a semblance of order in the camp. Doc, Jane, and Trixie have a minimal relationship with capital and profit. Historically, Deadwood was the child of Custer’s inflated claims about gold in the Black Hills — a treaty-violating foundation that amounts to one of the gravest atrocities against Indigenous people of its time.

Gold is a catalyst, but Deadwood isn’t exactly about it. It’s the commodity which propels the camp’s economy. Gold-panning occurs in the background while the bulk of the cast perform their affairs with profit accumulated from it. In effect, the lead characters form their own economic class, a community atop the gold trade, carrying out its own affairs.

At first glance, this undermines a commitment to Milch’s notion of community. Which isn’t a flaw — the idea of an 1870s mining camp built on exploitation, genocide, and murder where characters forge positive relationships while performing from or profiting off of evil is vastly more interesting than a straightforward class solidarity commentary could ever be. In fact, that evil is the closest thing to a unifying principle that Deadwood has. All of the cast is culpable for the camp’s original sin of stealing the mountains for gold. No one character is virtuous and without foibles — Doc Cochran spends the entire show in mortal terror of reliving his failure to save his Civil War patients. Every character is trapped in sin, and painstakingly reckoning with it through language: “Announcing your plans is a good way to hear God laugh.”

When people made bad yet drastic choices, they’re more likely to double down and try to do right by the fucked standards of their new circumstances than radically change their new status quo. Frighteningly, committing to making better mistakes can be easier than the often preferable move of changing one’s own life.

This takes us back to Milch’s original Rome pitch, and specifically to Saint Paul. In Life’s Work, Milch cites Reverend Smith’s quotation of Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians as “what I wanted the show to be about, and what I believe about us as a species, […] expressed in its purest form.”

“By one spirit are we all baptized into one body, whether we be Jew or Gentile, bond or free, and have all been made to drink into one Spirit. For the body is not one member but many.”

Milch is right that this serves as a thesis statement for Deadwood. Yet it’s easy to miss the most crucial part of that thesis statement: that Smith develops seizures (which Milch stipulates is connected to religious visions), rapidly declines in health and dies by Swearengen’s hand, the patient of a mercy killing. Swearengen takes the Reverend’s values to heart — in a sinful hellhole like Deadwood, a tender act of violence is the way to practice virtue.

Saint Paul may well have related to that. Paul came up in Tarsus, a provincial town, outside of Judaism’s capital in Jerusalem. His murder of Christians was essentially a way to survive — to keep the Roman yoke from crushing his people’s backs further. When God speaks to Paul on the road to Damascus, he comes to term with the fact that he’s become a monster. His only reprieve is to become a maniac for God.

Paul’s notions of God’s forgiveness, like Milch’s and the Deadwood cast’s, seem largely rooted in his own need to be forgiven. If all human beings are contiguous, then virtue is shared by the community. The reading of Paul’s Epistles as essentially universalist (which, to my mind, is obviously correct) is clearly confirmed by Romans 11:30-32, in which Paul seems to predict that someday a lad from the New World will write a sprawling drama about killers, thieves, and forgiveness:

“Just as you were once disobedient to God but have not received mercy because of their disobedience, so they have now been disobedient in order that, by the mercy shown to you, they too many now receive mercy. For God has imprisoned all in disobedience so that he may be merciful to all.”

If sin is shared, so is salvation. David Milch seems to leap for joy at the prospect. “We are organs of a larger organism which knows us although we do not know it.” Life’s Work: A Memoir is an understated title — the book is less a memoir than an act of contrition. As Milch states, “it increasingly seems that life is something that happens to you and art the opportunity to understand what’s transpired.” Language, it seems, isn’t a virus but a tool for bargaining with our own fallen nature. And to David Milch, Al Swearengen and Saint Paul, original sin isn’t merely some curse. It’s the sole organizing principle that redeems us all.