A Map of Causality (The Last War in Albion Part 21: Alan Moore’s Doctor Who Comics)

This is the third of seven parts of Chapter Four of The Last War in Albion, covering Alan Moore’s work onDoctor Who and Star Wars from 1980-81. An ebook omnibus of all seven parts, sans images, is available in ebook form from Amazon, Amazon UK, and Smashwords for $2.99. The ebook contains a coupon code you can use to get my recent book A Golden Thread: An Unofficial Critical History of Wonder Woman for $3 off on Smashwords (the code’s at the end of the introduction). It’s a deal so good you make a penny off of it. If you enjoy the project, please consider buying a copy of the omnibus to help support it.

“Increasingly observers describe the War as a shape rather than a secquence of events, a map of causality.” – Lawrence Miles, The Book of the War

PREVIOUSLY IN THE LAST WAR IN ALBION: Alan Moore was given his first straight writing job – backup comics for Doctor Who Weekly – on the recommendation of his friend Steve Moore. His first two stories were four-parters constructed of two-page chapters, but even in this early work hallmarks of Moore’s iconic style…

|

| Figure 157: Sinister smiling figures stepping noiselessly forward in Doctor Who Weekly #41 (Alan Moore and David Lloyd, 1981) |

What’s immediately interesting about Moore’s early Doctor Who work is that his second story is no less metered in its narrative, but that it has an entirely different tone. Where Black Legacy sticks mostly to iambic tone, Business as Usual goes for dactyls and trochees, as with the line, “NO one RAISED an EYEbrow when BLUNT inVESTed his CAPital in FOUNDing his OWN PLASTics COMPany. IT was JUST SOUND BUSiness.” Again, the meter is not strict, but it repeatedly puts the emphasis at the beginnings of phrases, favoring three-syllable feet with words like “capital” and “company.” These longer feet give the work a very different feel, as does the triple stressed syllable in “just sound business,” which draws considerable attention to that specific and seemingly mundane phrase, quietly exposing the underlying deception, namely that, far from being ordinary sound business, Blunt’s decision is in fact part and parcel of an alien invasion. Black Legacy feels clipped, and like it’s working in a more classical, epic sense, where Business as Usual sounds mundane and conversational. It’s slightly too wordy, resembling the obfuscatory language of stereotypical corporate jargon. Business as Usual also features, in places, highly alliterative phrasing such as “the sinister, smiling figure steps noiselessly forward. Behind, in the shadows, something stirs.” In twenty-three syllables Moore manages to get nine that feature an s sound. The effect fits perfectly into the milieu of sales and corporate branding that the larger story utilizes, highlighting its satirical bite.

But for all the cleverness of these two stories and all that Moore learned from the two-page chapter structure, it is, in the end, a limitation. Business as Usual suffers badly from having to recap its basic premise every other page. Where the first chapter can luxuriate in its droll humor and contrasts, once it has to start recapping its tone in a page or two it falters badly. On top of that, the fact that Moore is stuck writing Doctor Who stories without Doctor Who in them is a problem. Using the Autons as a comment on 1980s corporate culture is a phenomenal idea. Indeed, when Russell T Davies brought the Autons back for the first episode of the 2005 Doctor Who revival he almost directly apes Moore’s central joke, having Doctor Who explain to his companion, who speculates that the aliens are “trying to take over Britain’s shops,” that “it’s not a price war. They want to overthrow the human race.” But with eight pages and no Doctor Who there’s not much that Moore can do beyond have it descend into a fairly basic story about a man and an evil alien fighting and blowing things up. It’s not that Moore handles it badly so much as that there’s something of an upper bound to the inventiveness available to a story told in four two-page chapters.

|

| Figure 158: It is ambiguous, in this Fantastic Fact, whether the man or the leg is called Bumper Harris. |

This two page structure, however, was a peculiar artifact of where Doctor Who Weekly was at the time. The final installment of Business as Usual appeared in Doctor Who Weekly #43, the last issue before it abandoned weekly publication and rebranded as Doctor Who Monthly. As Doctor Who Weekly the magazine was primarily a comics magazine, cramming in reprints of old Marvel stories as “Dr. Who’s Time Tales” and reprints of 1960s Dalek strips alongside pages like “Fantastic Facts,” which dutifully informed the reader of such important if contextless facts like that “the egg of the ostrich is six to seven inches long and (if you were thinking of having one for breakfast) they take 40 minutes to boil.” As part of the profusion of comic strips the backup feature for the final few months was shortened to two-page chapters from its previously longer length, making it a particularly unattractive strip. The overall package was twenty-eight pages long, and sold for 12p.

Come issue #44, with the magazine renamed Doctor Who Monthly, the magazine expanded to thirty-six pages, jumped to 30p, and began featuring more detailed behind-the-scenes features and synopses of old stories. Sillier features like Fantastic Facts persisted, but the comics were pared back to two features, a main one starring Doctor Who and a backup feature, initially the tail end of Steve Moore’s Star Tigers. By the time of Moore’s final contribution in Doctor Who Monthly #57 silly features like “Fantastic Facts” were banished entirely, and instead the magazine was comprised almost entirely of behind-the-scenes features and retrospectives on the program. Over this transformative year Moore published three further backup features: “Star Death,” “The 4-D War,” and “Black Sun Rising.” These three stories are typically described as the 4D War Cycle, and tell related but bespoke stories about a war fought by the Time Lords against the mysterious Order of the Black Sun.

The first of these stories, “Star Death,” goes back to the earliest days of the Time Lords (Doctor Who’s species) – indeed, to the very point at which they became lords of time, namely their harnessing of the energy of Qqaba, a star in the process of collapsing into a black hole. Their preparations are interrupted by a mercenary named Fenris, who has traveled back in time to undo the Time Lords by sabotaging their experiments by disrupting the “protective haloes” keeping the Gallifreyans’ ships from plunging into the black hole. But Fenris’s sabotage is stopped when Rassilon, the force behind the Gallifreyan experiments into black holes, proves unexpectedly able to reactivate the haloes with his mind. Rassilon calmly dispatches Fenris with lightning from his finger (‘he would call it electro-direction. We would call it magic.”) knocking off his belt so that he cannot control his time travel anymore, resulting in him having his atoms “spread from one end of eternity to the other.” But though the basic power of time travel is now the Gallifeyans’, they still have not created a means of controlling their travel. Rassilon, meanwhile, ponders the belt he shot off of Fenris, and calmly takes the directional control off of it in order to create the desired means, thus creating a neat little temporal paradox.

|

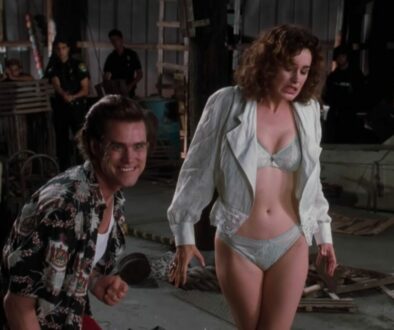

| Figure 160: Wardog is impressively stoic. (Alan Moore and David Lloyd, “4-D War,” Doctor Who Monthly #51, 1981) |

The second, “4-D War,” takes place twenty years after “Star Death,” and features Rema-Du, the daughter of two of the characters in that story, teaming up with Wardog, a member of the Special Executive, to plunge into the void and retrieve Fenris so he can be interrogated and the Time Lords can find out who attacked them. They do so, but just as the Time Lords discover the names of their opponents, the Order of the Black Sun, the Order itself shows up en masse, killing eleven (including Fenris) and severing Wardog’s arm. (When this is pointed out to him, he laconically responds, “Great God, my Lady! So they have!”) When Rema-Du anguishedly demands to know why this has happened, proclaiming that the Time Lords have done nothing to deserve this attack, her father sadly notes that they have not yet done anything to deserve it.

Finally is “Black Sun Rising,” which features a trade conference between the Time Lords and the still-peaceful Order of the Black Sun, which the Sontarans attempt to sabotage by mind-controlling a member of the Special Executive to assassinate the leader of the Order. But instead of sabotaging relations and driving the two groups to war, Wardog figures out the ruse and kills the Sontaran, suggesting that the Order of the Black Sun and the Time Lords are, for now at least, allies.

There is something altogether more interesting going on in the 4D War Cycle. Although each story is a self-contained number that builds to a mild twist ending, they are chapters of a larger story that is demonstrably being told out of order. The story gestures constantly towards a grander epic with the scale of his abandoned Sun Dodgers, but one that has been broken into manageable parts and is masquerading as a series of short stories. Given that these are still some of the earliest things Moore has written (“Star Death” appeared at the end of 1980, at which point Moore’s only other credits as a pure writer were a quartet of short stories for 2000 A.D.), this confidence is impressive, and quietly belies his suggestion that a sizable apprenticeship on short stories is a vital step in learning to write comics.

And yet the 4D War Cycle is, in the end, still a collection of short stories. In many ways this makes the swaggering scope of it all the more impressive. It would be one thing to, after a handful of short works, go right back to attempting a three hundred page epic. It is quite another to decide to merge the vast, epic structure with another mode of storytelling. It’s also worth noting the inventiveness of what Moore does in these comics. At the time he wrote them, Doctor Who, despite having been on the air for over seventeen years, had never really done a story focusing on time travel as anything other than the macguffin needed to start a story. Doctor Who uses a time machine to arrive at the location of a given adventure, but with only a handful of exceptions the time machine is never involved in the plot after that, and is essentially never used to create causality paradoxes and non-linear storytelling.

|

| Figure 161: The Faction Paradox series tells of a non-linear “War in Heaven” fought over the nature of history itself, and has lots of people wearing skull masks. |

This is not a problem as such for Doctor Who – there are ultimately more stories to be done in the mould of “Doctor Who shows up somewhere and has an adventure” than there are using the well-worn tropes of time travel. But it’s still telling that Moore dramatically expanded the scope of what Doctor Who could do, doubly so given how flexible a format Doctor Who was to begin with. It’s also telling that Moore’s expansion of Doctor Who’s premise stuck and had considerable influence. The idea of a “time war” became a major feature of Doctor Who in the 1990s when it reincarnated post-cancellation as a series of novels, and is a fundamental element of the mythology of its post-2005 incarnation, which, under writer Steven Moffat, is as addicted to causality paradoxes and non-linear storytelling as Alan Moore is to iambs and using the same image at the start and end of a story. And the similarity is not accidental – Russell T Davies, who established the Time War for the post-2005 series, is a die-hard comics fan who explicitly referenced the Deathsmiths of Goth from Black Legacy in a Doctor Who prose piece he wrote. And Davies is hardly the first person involved in Doctor Who to draw from Alan Moore. Lawrence Miles, who wrote much of the “time war” stuff in the 90s, which he spun off into the independent Faction Paradox franchise, has cited Moore as a major influence on his work. Andrew Cartmel, who script-edited the series for its final years at the end of the 80s, drew from Moore’s work repeatedly, and even invited Moore to write for the show, an offer Moore declined. (Cartmel would go on to script one portion of Alan Moore’s The Worm

Admittedly some of this influence is simply the fact that Alan Moore is one of a tiny handful of respectable literary writers to have gone anywhere near Doctor Who, and his involvement with it, even if it’s only twenty-eight pages of out-of-print comics from the earliest days of his career, adds respectability to the show. Given this it is perhaps telling that Christopher Priest, a “proper” literary writer, made extensive use of causality paradoxes in Sealed Orders, his abandoned script for the television series written around the same time as Moore’s comics. The ideas Moore offered, in other words, were in many ways “in the air” at the time. It’s unfair to treat Moore’s ideas here as entirely novel and visionary. By his own admission, the Order of the Black Sun is an unsubtle rip-off of DC’s Green Lantern Corps, which Moore, as a British writer, assumed he was never going to get to write. What is innovative here is not so much the ideas as applying them to Doctor Who.

Furthermore, on the evidence available, it’s impossible to judge Moore’s larger ambition. The three existent stories leave much about the 4D War unexplained. The nature of Rassilon’s seemingly magical and godlike powers in the opening chapter hints at some larger and more mysterious role intended for him. The actual provocation of the war between the Time Lords and the Order of the Black Sun remains unclear. As does the actual outcome of the war. Moore did not write a sprawling epic of a non-linear war; he wrote a couple of early chapters of something that could plausibly have expanded into one.

Moore was, apparently, intending to further flesh out his idea of a non-chronological war further, but circumstances intervened. Instead left the title along with Steve Moore, who had worked extensively on a plot outline for a third Abslom Daak story only to discover that the editor, Alan McKenzie, had already begun writing a story with the characters. Angered by this, Steve Moore abruptly quit the main title and was replaced by Steve Parkhouse, and Alan Moore followed suit in what Steve Moore has referred to as “a wonderful gesture of support that was remarkable for someone at that early a stage in their career.” While it’s true that Moore, who had not come close to establishing himself as a writer, took a genuine professional risk in quitting, the fact that he did so early in his career is the only remarkable thing here. It is, in fact, the first of many such gestures in his career.

December 5, 2013 @ 5:47 am

This comment has been removed by the author.

December 5, 2013 @ 5:51 am

'While it’s true that Moore, who had not come close to establishing himself as a writer, took a genuine professional risk in quitting, the fact that he did so early in his career is the only remarkable thing here. It is, in fact, the first of many such gestures in his career.'

In fact it happens rather a lot doesn't it? Are you going to propose any theories as to why? Given the depressing frequency that he does it it does strike me sometimes as quite an immature response. Like a kid stomping out of the playground saying "It's my bat and my ball and I'm going home!". I'm not suggesting that Moore is unjustified in his actions, just that every time he does it it becomes more depressingly predictable.

As far as his work on the Doctor Who comic strips goes – at the time I loved that a writer was finally addressing what to me was the elephant in the room. Doctor Who is both about Time and Space and could, potentially, be as cosmic as the American comics I loved – Green Lantern, The Legion, Mar-Vel and the Kree/Skrull stuff etc. It's clear, in light of their later work, that that's where both Moore and Morrison's inspiration lay also.

I thought the Order of the Black Sun was an intriguing mash-up of the Order of the Golden Dawn, the Order of the Knights Templar and the Black Sun imprint of Harry Crosby; Poetically conflating a black sun with a black hole and linking it to the Rassilon/Omega mythos to spark an interdimensional war was one of those throwaway strokes of genius that Moore would become known for.

By the way have you any idea why he turned down the offer to write for the TV show?

December 5, 2013 @ 6:03 am

My understanding (which may be inaccurate or incomplete) is that Cartmel's offer came around the time Moore was beginning to be disenchanted in his work for DC, and the prospect of writing for another character/franchise which he did not own did not appeal to him. Plus, he's on record as saying that all Doctors since the first have seemed like pedophiles to him.

December 5, 2013 @ 6:41 am

You know, it hadn't occurred to me until Phil drew our attention to it in this post that Russell T Davies stole the notion of Rassilon shooting electricity from his fingers from Alan Moore.

December 5, 2013 @ 6:46 am

Yes I've seen that quote before. It's just Moore being 'clever and controversial' though isn't it? It doesn't bear much scrutiny. If anything the first Doctor is the only incarnation who could possibly suffer from that accusation. Living alone in an East-End junkyard with his 'grandaughter', investigated by her teachers who he violently abducts. On his return to London a few years later without his 'grandaughter' but with another young girl he hangs around in a night club where his similarity to 'that DJ' Jimmy Saville is noted by a young girl and a sailor who he also abducts while the other young girl who was travelling with him also mysteriously disappears.

Anyway I'd love to see a Doctor Who story written by either Moore or Morrison. I wonder, now Gaiman's done a couple, whether that's more or less likely?

December 5, 2013 @ 7:49 am

I think either Moore or Morrison would be good but I suppose both of them would really only shine if they write some major plot arc.

December 5, 2013 @ 8:03 am

That's it! You Win! I'm calling him "Doctor Who" from now on.

December 5, 2013 @ 8:35 am

What? Isn't that his name? Seriously, I thought the boat had sailed on that piece of elitist fanwankery ages ago. Extra-diagetically 'Doctor Who' is both the name of the show and the protagonist. Within the narrative (apart from the non-canonical Cushing movies) the protagonist is called the Doctor, the Caretaker, the Valeyard, The Oncoming Storm, The Curator, Theta Sigma, Grandfather or John Smith. Not so seriously – I laugh out loud every time Phil does that in the 'Albion' posts.

December 5, 2013 @ 8:51 am

"Christopher Priest, a “proper” literary writer, made extensive use of causality paradoxes in Sealed Orders, his abandoned script for the television series written around the same time as Moore’s comics."

Does anyone know of good sources of information about Priest's two scripts? I keep hoping that they might turn up as Big Finish Lost Stories. This might be more likely now that Baker I is doing audios, although I wouldn't be surprised if Priest weren't interested.

December 5, 2013 @ 11:18 am

Ever since Phil said he was writing the Doctor Who references in a way designed to wind up fans, I've been waiting for a reference to "Whovians".

December 5, 2013 @ 12:27 pm

and 'screaming assistants'.

December 5, 2013 @ 2:28 pm

'wobbly sets'

December 5, 2013 @ 5:24 pm

One problem with Big Finish doing "Sealed Orders" is that it was written as Romana's exit story, and its plot is closely tied in to that. Big Finish tends to try to keep their "Lost Stories" roughly consistent with existing continuity, don't they? Would they do a "Lost Story" that contradicted a story broadcast on TV for a major character?

December 5, 2013 @ 6:05 pm

Another problem is that Big Finish have announced that they are ending the Lost Stories range with the next release (The Mega). I remember hearing that they have run out of scripts/treatments that are workable and clearable, so I assume that Sealed Orders has already been considered and dismissed.

Then again, I never thought they'd be able to get Ward and Baker teaming up at all – so anything's possible.

December 5, 2013 @ 11:50 pm

It would probably be possible to align "Sealed Orders" with the TV/BF continuity with a little tweaking. Now that Ward is back, the possibility of a full audio of SO does present itself. There's also "The Enemy Within", Priest's Davison's story that would have seen the exit of Adric, so that one wouldn't be particularly easy to work into the continuity either. I suspect though that Priest has been asked and has said no, which is understandable given the appalling way he was treated in the early 1980s, even though neither JN-T or Saward have anything to do with BF. I'm a big Priest fan and would buy SO and TEW in a heartbeat should they be produced.

December 6, 2013 @ 1:50 am

Morrison has actually pitched to the current production team.

December 11, 2013 @ 5:08 am

The Wardog comment is a reference to an exchange between Lord Uxbridge and the Duke of Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lord_Uxbridge's_leg