All Coppers Are Rascals (The Last War in Albion Part 92: Raoul’s Night Out, and Later Tales)

This is the fourth of eleven parts of The Last War in Albion Chapter Ten, focusing on Alan Moore’s Bojeffries Saga. An omnibus of all eleven parts is available on Smashwords. If you are a Kickstarter backer or a Patreon backer at $2 or higher per week, instructions on how to get your complimentary copy have been sent to you.

The Bojeffries Saga is available in a collected edition that can be purchased in the US or in the UK.

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Following their initial two-part story, Moore and Parkhouse wrote a second two-part Bojeffries Saga strip for Warrior entitled “Raoul’s Night Out.”

“All Coppers are Rascals.” -Ol’ Bill, Dodgem Logic #3

|

| Figure 702: Sheena, a clear parody of Vyvyan Basterd. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Steve Parkhouse, from “Raoul’s Night Out,” in Warrior #20, 1984) |

The story also marks a subtle evolution to the underlying format of The Bojeffries Saga. The plot is still basically that of a farce, but instead of focusing on one character in a traditional “idiot” role, he layers together a set of absurd misunderstandings incorporating several characters, all of whom are, in their own ways, complete dunces. But what’s in many ways more important than the change in comedic structure is the nature of the characters involved. The first story was, at the end of the day, essentially a Hogben story transplanted to working class Britain, with the focus firmly on the eccentric family and Trevor Inchmale as an intrusion from the mundane world. But “Raoul’s Night Out” is a story about working class Britain into which a single werewolf has been inserted. This allows Moore to engage in a fairly direct satire of the working class. For instance, among Raoul’s coworkers is Colin Council Estate, who introduces his girlfriend Sheena,to Raoul by saying “society’s rejected ‘er because she’s got ‘**** off’ tattooed on her forehead” (a fairly straightforward homage to Vyv of The Young Ones).

|

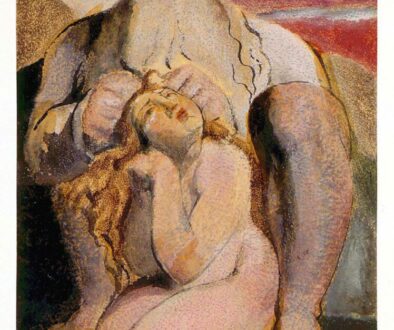

| Figure 703: Cops beating a black man. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Steve Parkhouse, from “Raoul’s Night Out,” in Warrior #20, 1984) |

The move to looking at the larger culture in which the Bojeffries exist allows Moore a considerably sharper sort of satire. The main thrust of “Raoul’s Night Out” is a night out with Raoul and his coworkers that goes wrong for a number of reasons, not least of which is that Colin consulted his diary to tell Raoul that it was a new moon without bothering to mention that, as Sheena puts it, his “***** diary is four ***** years old” and that he hasn’t “bought one since the *** Pistols disbanded.” This, rather awkwardly, results in Raoul turning into a wolf in the middle of dinner, which causes further deterioration in a situation already made fraught by Raoul’s passing on a pamphlet given to him by his coworker Stanley to another one of his coworkers, George, completely unaware of the fact that Stanley’s neo-Nazi propaganda (“Did Himmler Discover Radium,” one article asks) might go down poorly with George, who is black. By the story’s end George and Stanley are in the midst of a furious row, Little Nigel (who Moore, in an interview, describers as “a teddy boy dwarf”) is discoursing at length about his habit of going to the Yachting Club and molesting women while pretending to be drunk, and Raoul is a wolf, at which point the cops burst through the window of the restaurant, take one look at the situation, and proclaim that “it’s fairly obvious what the source of the trouble is here” before violently beating George and dragging him off. (“Y’know, I’m not racial predjudice, but they ent the same as us, are they,” muses Little Nigel to Stanley afterwards.)

But for all that “Raoul’s Night Out” goes for incisive comment on British racial politics, its main focus is simply on the odd ritual of the night out with one’s coworkers. The story ends with Raoul returning home and telling Jobremus the story of the night, to which Jobremus sadly shakes his head and says, “Honestly, our Raoul… you are a gret wally… I dunno why you bother to go every year if it’s always the bloody same,” at which point caption boxes take over, narrating that “the evening was still, save for the faint whirring noises that the streetlamps made if you pressed your ear to them and the distant, poignant coughing of a consumptive housemartin. Goodnight, everybody. Goodnight. The joke, in other words, isn’t just that British cops are racist or that punks are not the most reliable people ever born, but rather that this sort of farce is perfectly ordinary – as Moore put it, “I didn’t have to reach back so far in my memory to bring out Raoul’s Night Out. That was thinking back to my late teens and early twenties where I was in the world of work and experienced work nights out for myself, which were always kind of nightmarish, if oddly entertaining in other ways.”

“Raoul’s Night Out” was the final Bojeffries Saga strip to appear in Warrior. It was not, however, the final Bojeffries Saga strip in general. The degree to which one finds this surprising is perhaps a matter of perspective. From one angle, it would have been odd for it not to continue, in that it would have been the only one of Moore’s three Warrior strips not to carry on elsewhere. But the migration of Marvelman to Eclipse and V for Vendetta to DC was, in each case, due to the acclaim and popularity those strips had attracted, and this acclaim was based on a specific and ultimately narrow view of Alan Moore’s style as a writer whereby his “serious” works with inventively gruesome violence and high body counts are considered his most important. The Bojeffries Saga was, self-evidently, not going to follow precisely in the footsteps of Moore’s other Warrior strips. Indeed, it’s remarkable that it did so to any degree – it initially consists, after all, of just twenty-six pages of material. There aren’t really any other examples in Moore’s career of something that short getting followed up on years later, and certainly none that are comedic in nature.

And yet not only was The Bojeffries Saga followed up on, it has the distinction of being the work in Alan Moore’s career with the single longest span between its first and most recent installments, with thirty-one years transpiring between “The Rentman Cometh” and the final Bojeffries story, “After They Were Famous.” And yet for all of this, there is no point in Moore’s career where The Bojeffries Saga can ever be called a major concern – at its most active period, Moore and Parkhouse produced thirty-four pages over three years, and those were the same years during which Moore started From Hell, Big Numbers, and Lost Girl and wrote both Brought to Light and A Small Killin; The Bojeffries Saga is hardly a major work of the period. And so The Bojeffries Saga is in the curious position of simultaneously being able to demonstrate the entire expanse of Alan Moore’s career and never really giving a particularly good sense of it. In this regard, it is possibly the most revealing and significant document of the pre-War period.

Moore and Parkhouse’s first return to the terraces came in 1986, when they penned a four page prologue to “The Rentman Cometh” for Fantagraphics’ Dagoda entitled “Batfishing in Suburbia” and described as “a preface to the American edition.” Its main purpose is to engineer a subtle but significant shift to how The Bojeffries Saga introduces itself. Appending it to the start of the story means that instead of being introduced to the world through Trevor Inchmale’s encounter with the uncanny, the story is introduced in terms of the Bojeffries, specifically a sequence in which Jobremus and Reth engage in the traditional family pastime of batfishing, which is to say, of fastening a harness onto a drunken moth and using it as bait to catch bats, a ritual Jobremus, recalling when Podlasp took him batfishing, describes as “a turning point in a boy’s life.” In the middle of this is a brief sequence – just over a page in length – introducing Trevor Inchmale as he’s scolded to go to bed by his mother (with whom he apparently lives) who proclaims, “I know what you’re doing in there! You’ll ruin your eyesight, that’s what you’ll do.” What he is doing, of course, is reading nineteenth century rent records and discovering the arrears of the Bojeffries, a rent arrears of such a staggering amount that, once he goes to bed, causes him to remark, “something’s happening in my pyjamas.” Meanwhile, back on the roof of the Bojeffries house Reth catches his first bat, causing Jobremus to exclaim that “this is grand! This is what England’s all about! Family traditions passed on from generation to generation, like the monarchy.” They manage to reel the bat in, at which point Jobremus bashes its head against the chimney and throws it away, as “after that, they’re not much good.” Reth, puzzled, asks what the point is. There’s an awkward pause, Jobremus instructs him to drink his Bovril, and a caption box proclaims, “The night wore on, and a fine drizzle of ironies in the small hours led to a bout of serious events just before morning. All the next day there were scattered circumstances. That’s how it was in England.”

|

| Figure 705: A splash page added to the 1992 Tundra reprint of The Bojeffries Saga. |

The effect of this is to ground the world of the Bojeffries as the central reality of the strip, as opposed to starting with a mundane (if clearly eccentric) figure. True, there is nothing supernatural revealed about the Bojeffries in this strip; the practice of batfishing is clearly ridiculous, and the idea of making sure that a moth harness is “not too tight around the crotch” is clearly outside the realm of human possibility, but it nevertheless falls markedly short of lycanthropy. All the same, it removes any sense that this might be a story about Trevor Inchmale, who, structurally, is clearly the (equally absurd) antagonist of the piece (although the connection between the two narratives is merely implied). But perhaps the more significant change is one of tone – instead of the first thing the reader learns about the Bojeffries being that they’re a century behind on rent and have a psychotically violent woman named Ginda in their family, the reader sees a silly but nevertheless idyllic vision of the family. Perhaps more to the point, however, it demonstrates an idyllic vision of the British landscape that the Bojeffries inhabit. “Batfishing in Suburbia” is particularly long on Parkhouse landscapes – fifteen panels over the course of its four pages give Parkhouse opportunities to draw skylines and architecture, almost all of it in a soft moonglow, providing a particularly vivid effect in the colourized Tundra collection. In the collected editions, the story is followed by a splash page of the Bojeffries house from the perspective of its back garden, thus on a cliff face overlooking the sea, with gulls circling and the moon shining bright behind the chimney, the face of Trevor Inchmale carved out of the rocks, making the sense of the Bojeffries’ world as a sort of loving nostalgia unmistakable.

|

| Figure 706: The unorthodox seduction techniques of Ginda Bojeffries. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Steve Parkhouse, from “Sex with Ginda Bojeffries” in A1 #2, 1990) |

The next wave of Bojeffries Saga work spanned from 1989 to 1990, and came out in Garry Leach and Dave Elliott’s A1, an anthology out of which sprung a couple of odd little footnotes to the War, including a second Moore/Leach Warpsmiths strip entitled “Ghostdance,” a Glenn Fabry-illustrated Axel Pressbutton strip from Steve Moore, writing under his Pedro Henry pseudonym, and, in the fourth issue, another of the handful of times Alan Moore and Grant Morrison were published in the same magazine as Morrison and Dom Regan’s “The House of Hearts Desire” saw print alongside the Bojeffries strip “A Quiet Christmas With the Family.” The five Bojeffries Saga installments to see print in A1 divide into, essentially, two categories. The first are three strips in the same general vein as “Raoul’s Night Out” – character pieces that take a single member of the Bojeffries clan and look at them to the near-exclusion of all other family members. The first of these, “Fetus: Dawn of the Dead” tells the story of the vampiric Festus over the course of three days as he tries to go about his basic business without any untimely incinerations, a task he fails spectacularly at, suffering fates such as being branded by the cross upon a sweet bun, or terrified by a paperboy offering him the Mirror or the Sun. The second, “Sex with Ginda Bojeffries,” largely does what it says on the tin, making humour out of Ginda’s fundamental misunderstandings regarding sex, such as her attempt to fake orgasm by shouting “listen… I’m making short, sharp cries, like an animal in pain! Ouch. Ouch, my paw! Ouch,” and ending with a caption describing how “somewhere, a biological clock chimed the hour. As a familiar and unpleasant weight rolled on top of her, England lay back, closed her eyes, and thought about sex…”

|

| Figure 707: Reth dreams of comics. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Steve Parkhouse, from “Our Factory Fortnight” in A1 True Life Bikini Confidential, 1990) |

The third, “Our Factory Fortnight,” is something of a special case. Published in the A1 True Life Bikini Confidential special, it is the only Bojeffries Saga strip to make its debut in color, with Parkhouse providing a red inkwash to his illustrations, a decision that was retained both in the full color Tundra collection and the otherwise monochrome Top Shelf/Knockabout one. On the one hand, it is another character-focused piece, this time looking at the world through Reth’s eyes, and focusing specifically on the annual Bojeffries family vacation to the Sparklesands caravan camp. (“Apparently, since last year there’s been a full enquiry to find out exactly why the sands were sparkling, and now everybody’s advised to hire lead wind-breaks and all the deckchairs have had to be encased in concrete until the year six thousand,” Reth notes.) In addition to the ink wash, “Our Factory Fortnight” is a structural experiment, written not as a straight comic, but as series of eighteen pictures and captions, in the style of countless low-rent British comics annuals and summer specials (the latter of which were generally published specifically so that they could be sold in vacation towns like the one depicted in “Our Factory Fortnight,” which, indeed, features Reth dreaming about such comics).

|

| Figure 708: Paperboys serenading the terraces. (From A1 #4, 1990) |

The other two A1-published Bojeffries Saga strips were “A Quiet Christmas With the Family” and “Song of the Terraces,” both of which moved away from the single character spotlight. The former is a relatively straightforward strip in which Moore and Parkhouse run through the obvious gags surrounding the idea of a Bojeffries family Christmas (Raoul eats a reindeer, Grandpa is upset to be given a gift token for a pet store instead of a sacrifice of white goats, and Festus is incinerated when Reth excitedly proclaims “God bless us every one”), but the latter is one of the most interesting and formally inventive Bojeffries Saga stories to date. Described as “a light opera with libretto by Mr. A. Moore and full orchestration by Mr. S. Parkhouse,” the strip is formatted as a musical, beginning with the chant of a paperboy as he walks down the terraced street, identifying the paper of choice of each house he walks past: “Sun, Sun, Sun, Sun, Sun, Guardian, Sun.” He is quickly joined by further paperboys, taking up his chorus and adding in descriptions of the papers’ contents: “Page three, transfer fee, ‘Is your man a sex bomb?’ [continued]

April 17, 2015 @ 8:29 am

A1 was such a fun book; in a lot of ways it was the anthology people wanted Warrior to be. A couple minor points, though: “The House of Hearts Desire” and “A Quiet Christmas With the Family” were in issue #3, not #4. And "Our Factory Fortnight" was in black & white in the True Life Bikini Confidential special, without the red wash.

"Song of the Terraces" is just an amazing little story; it's pretty much the only time I've ever actually felt like I've heard a song in a comic. Which doesn't stop others, and Moore himself, from occasionally trying and failing to convey the effect elsewhere.

April 17, 2015 @ 10:49 pm

Man I remember A1 too – what a blast from my past! they were great volumes. Really enjoying reading about the Bojeffries saga, I am sure I would have read some of it back in the day but had little memory of it.

Figure 705 is a pretty amazing piece of artwork.

April 18, 2015 @ 11:21 am

A1 is also, of course, one of the key early fronts in the war. In the 7 issues, not only do Moore and Morrison show up, but Neil Gaiman and Warren Ellis are also in there. Other than the almost impossible to find Food for Thought, which gets 3 of those creators in a single issue, it's hard for me to think of a more concentrated front of the war. (2000 AD gets everybody at some point, but spread out over a fairly wide range of progs.)

April 19, 2015 @ 9:02 pm

(a fairly straightforward homage to Vyv of The Young Ones)

A real stretch, I think – the typographical joke is the point, so the slight visual similarity is more likely a coincidence.

Fantagraphics’ Dagoda

Dalgoda. Possibly worth mentioning that the rest of the Warrior material (iirc) was colourised and run as backups in Dalgoda subsequently, as an example of how Moore was making his incursions into American territories on multiple fronts at this time? It seems clear that the ready lure of readies was all that distracted him back towards DC over and over, as the AH Preview Special listings for “Alan Moore’s Comic” and “Dodgem Logic” failed to deliver on the Fantagraphian promise of In Pictopia, year after year.

May 11, 2015 @ 10:07 pm

I thought I could hear the loo-oony song in "The Killing Joke."

June 10, 2015 @ 9:00 pm

really very interesting article and i love way you write the article, So please keep writing and hope some best and cheap writing service service will help you to know more about the writing.

December 6, 2015 @ 10:15 am

genuinely very interesting i and content love way you write down the content, So you need to maintain crafting