A Vermin Race (The Sea Devils)

It’s February 26th, 1972. Between now and April 1st, 125 will die in a coal sludge spill in West Virginia, 19 will die in an avalanche on Mount Fuji, and the Easter Offensive wll begin in the Vietnam War, lasting into Octoer and resulting in somewhere between fifty and a hundred thousand deaths. In addition, M.C. Escher will die in a hospital in the Netherlands, the world will inch ever closer to the eschaton, and The Sea Devils will air.

It’s February 26th, 1972. Between now and April 1st, 125 will die in a coal sludge spill in West Virginia, 19 will die in an avalanche on Mount Fuji, and the Easter Offensive wll begin in the Vietnam War, lasting into Octoer and resulting in somewhere between fifty and a hundred thousand deaths. In addition, M.C. Escher will die in a hospital in the Netherlands, the world will inch ever closer to the eschaton, and The Sea Devils will air.

Within the innate conservatism of the Pertwee era, Malcolm Hulke remains one of the most interesting figures. At one point in his life, he was a member of the Communist Party, and while this membership at some point lapsed, he appears to have been a lifelong socialist and leftist. And yet the era of Doctor Who he’s associated with is one of its most resolutely conservative. More to the point, his stories are not the ones that most challenge that tendency. Three of his Pertwee stories are earth-based military action pieces that trend away from the era’s nominally progressive glam instincts. The other two are space-based stories displaying the most uncomplicated liberalism imaginable. The overall impression is of the sort of bland centrist who imagines himself to be progressive—a Buttigieg voter, to use a contemporary metaphor.

But implicit within that image is the presence of some genuinely progressive instinct that is subsequently smothered under the blandness of centrist liberalism—a moment in which some sort of serious political engagement is entertained. And Hulke generally displays that as well—Colony in Space, with its setup of a bunch of working class miners oppressed by an evil corporation, is probably the clearest case, but the interest in the moral question of how legitimate the Silurians’ claim to the planet is in their eponymous story is also clear. In both cases, the end results are disappointing, but you can see the vague consideration of being interesting before the stories commit to their worst political instincts.

But neither of these stories compare with The Sea Devils, which elevates political confusion into an art form. On the one hand you have Hulke revisiting the concept of The Silurians. On the other, you have Barry Letts dictating that they do a propaganda piece for the Royal Navy. The result is a tangle of influences and directions. One case, pushed by Tat Wood, is that the story (at least as director Michael Briant conceives it) is about consumption, shot from a perspective where the Sea Devils are the sense of normality and the humans are the weird ones, as apparently evidenced by the (admittedly peculiar) frequency with which they’re seen eating and the odd camera angles. It’s certainly an interesting interpretation, but even Wood is forced to admit that it’s only marginally in the actual story. You certainly could do a story about the indigenous lizard people of the world and their horrified bewilderment at human consumption—it’s even a pretty good idea for a story.…

The rule, apparently, is that anyone talking seriously about this story has to start with Paul Cornell’s 1993 review of it. I’m not entirely sure why this is the rule—presumably because Cornell is surely terribly embarrassed by the review now that he’s firmly into the “everything is lovely, especially fandom and the Pertwee era, let’s all just get along and support New Labour” phase of his career instead of the “actually doing anything worthwhile” one. Or perhaps just because, in spite of Cornell’s latter day shame at having ever had interesting opinions, the review remains one of the most solid and important things ever said about the Pertwee era. It’s not that Cornell is correct per se—his vituperative denunciations of the entire cast along with everyone else involved in the story is excessive, not least in his claim that there are only two competent actors in the era, which more than doubles the actual number, although he at least correctly identifies one of them. It’s just that it’s petty, mean-spirited, and therefore exactly what the era needs, culminating in the utterly savage kicker that Barry Letts and Terrence Dicks “exiled the Doctor to Earth and made him a Tory.”

The rule, apparently, is that anyone talking seriously about this story has to start with Paul Cornell’s 1993 review of it. I’m not entirely sure why this is the rule—presumably because Cornell is surely terribly embarrassed by the review now that he’s firmly into the “everything is lovely, especially fandom and the Pertwee era, let’s all just get along and support New Labour” phase of his career instead of the “actually doing anything worthwhile” one. Or perhaps just because, in spite of Cornell’s latter day shame at having ever had interesting opinions, the review remains one of the most solid and important things ever said about the Pertwee era. It’s not that Cornell is correct per se—his vituperative denunciations of the entire cast along with everyone else involved in the story is excessive, not least in his claim that there are only two competent actors in the era, which more than doubles the actual number, although he at least correctly identifies one of them. It’s just that it’s petty, mean-spirited, and therefore exactly what the era needs, culminating in the utterly savage kicker that Barry Letts and Terrence Dicks “exiled the Doctor to Earth and made him a Tory.” It’s May 9th, 1970. Between now and June 20th, Henry Marrow will be killed in North Carolina in a racist hate crime, two will die when police fire into a crowd at a demonstration at Jackson State University, a fourteen-year old fan will die after being struck in the head by a foul ball at a Major League Baseball game, eleven will die in Israel in a Palestinian terrorist attack, six when a plane crashes into an Interstate Highway in Florida. In addition, E.M. Forster will die of a stroke, Abraham Maslow will die of a heart attack, and unnumbered people will die in the ongoing Vietnam War whilst the world slides ever closer to the eschaton. Also, Inferno airs.

It’s May 9th, 1970. Between now and June 20th, Henry Marrow will be killed in North Carolina in a racist hate crime, two will die when police fire into a crowd at a demonstration at Jackson State University, a fourteen-year old fan will die after being struck in the head by a foul ball at a Major League Baseball game, eleven will die in Israel in a Palestinian terrorist attack, six when a plane crashes into an Interstate Highway in Florida. In addition, E.M. Forster will die of a stroke, Abraham Maslow will die of a heart attack, and unnumbered people will die in the ongoing Vietnam War whilst the world slides ever closer to the eschaton. Also, Inferno airs. It’s November 2nd, 1968. Between now and December 21st, a mine explosion will kill seventy-eight in West Virginia, twenty-two will die in a factory fire in Glasgow, two will be shot by the Zodiac Killer, and numerous people will die in the Vietnam War, including 374 civilians in Laos when the US Military targets a cave in the incorrect belief that it housed Viet Cong troops and not refugees. In addition, Upton Sinclair will die in a nursing home in New Jersey, Enid Blyton will die in a nursing home in London, and John Steinbeck will die of heart failure in New York. A flu pandemic rages, ultimately killing one million, and the world drifts ever-closer to the eschaton. Also, The Invasion airs.

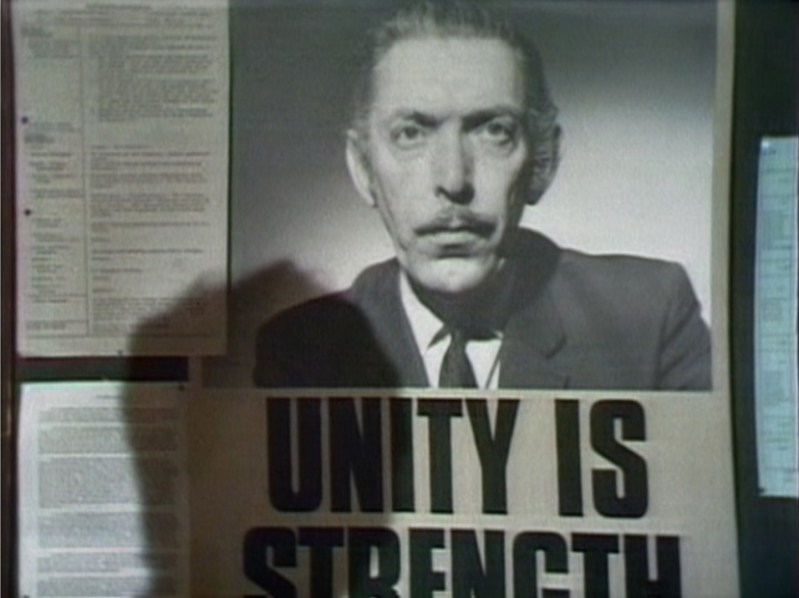

It’s November 2nd, 1968. Between now and December 21st, a mine explosion will kill seventy-eight in West Virginia, twenty-two will die in a factory fire in Glasgow, two will be shot by the Zodiac Killer, and numerous people will die in the Vietnam War, including 374 civilians in Laos when the US Military targets a cave in the incorrect belief that it housed Viet Cong troops and not refugees. In addition, Upton Sinclair will die in a nursing home in New Jersey, Enid Blyton will die in a nursing home in London, and John Steinbeck will die of heart failure in New York. A flu pandemic rages, ultimately killing one million, and the world drifts ever-closer to the eschaton. Also, The Invasion airs. It’s December 23rd, 1967. Between now and January 27th, thirteen people will die in England when a train collides with a truck that had stalled on the tracks, 380 will die in a Sicilian earthquake, and 121 will die in a pair of submarine crashes in the Mediterranean. In addition, Mike Casparak will die of liver failure fifteen days after being the first successful recipient of a human heart transplant in the United States, while Bill Masterton will die of a brain injury sustained during a National Hockey League game, and huge numbers will die in the still-continuing Vietnam War. Also the world will progress ever-closer to the eschaton, and The Enemy of the World airs.

It’s December 23rd, 1967. Between now and January 27th, thirteen people will die in England when a train collides with a truck that had stalled on the tracks, 380 will die in a Sicilian earthquake, and 121 will die in a pair of submarine crashes in the Mediterranean. In addition, Mike Casparak will die of liver failure fifteen days after being the first successful recipient of a human heart transplant in the United States, while Bill Masterton will die of a brain injury sustained during a National Hockey League game, and huge numbers will die in the still-continuing Vietnam War. Also the world will progress ever-closer to the eschaton, and The Enemy of the World airs.