It’s Funny, Isn’t It? (The Pirate Planet)

It’s September 30th, 1978. Between now and October 21st, three people will be murdered by Bruce John Preston in the Australian town of Mount Isa, numerous people will die in Cambodia following a Vietnamese invasion, and an unknown number of people die in the African National Congress following an attempt to poison 500 people to kill an unidentified infiltrator. Also, Frederick Valentich dies in an aviation accident shortly after encountering what he described as an unidentified flying object, Jacques Brel dies of cancer in France, the world comes closer still to the eschaton, and The Pirate Planet airs on BBC One.

It’s September 30th, 1978. Between now and October 21st, three people will be murdered by Bruce John Preston in the Australian town of Mount Isa, numerous people will die in Cambodia following a Vietnamese invasion, and an unknown number of people die in the African National Congress following an attempt to poison 500 people to kill an unidentified infiltrator. Also, Frederick Valentich dies in an aviation accident shortly after encountering what he described as an unidentified flying object, Jacques Brel dies of cancer in France, the world comes closer still to the eschaton, and The Pirate Planet airs on BBC One.

In The Pirate Planet, Doctor Who presents one of the most confused central metaphors of its long and generally confused history. The concept is admittedly ingenious: Zanak, a hollow planet that materializes around other planets and then consumes them in their entirety. On top of that, as is gradually revealed over the course of four episodes, all of this exists to feed power to the elaborate machines keeping the tyrannical Queen Xanxia alive and with a facsimile of her youthful body. So on the one hand we have a brutal metaphor for capitalist/imperialist expansion and the way in which it leads to devastating destruction purely for the benefit of a handful of parasitic elites.

On the other hand the final episode, in which Douglas Adams creates an added source of tension by establishing that Zanak’s next target is Earth, comes dangerously close to misunderstanding the entire affair. Suddenly the subject of the metaphor becomes a curiously guiltless victim of it. More to the point, however, this collapse of a story largely concerned with metaphor into a story in which the Earth is in imminent peril serves to highlight the fact that the central conceit—a planet that consumes other planets for wealth—dramatically misses the reality, which is that planets consume themselves.

This is doubly interesting when taken in the context of Douglas Adams’s larger career. Adams is an extremely easy writer to like—a jaw-dropping prosesmith with one of the wickedest senses of humor in literary history. And yet it is hard not to come to the conclusion that his reputation was helped enormously by the fact that he died in 2001. A brief perusal of Adams’s social circle, after all, does not turn up a long list of people who have enjoyed cancellation-free dotages. Instead you get people like Richard Dawkins, rightly pilloried as a racist, sexist old windbag, or Monty Python, whose surviving members seem increasingly determined to become edgelordy Brexiteers who complain about how people are easily offended snowflakes. Douglas Adams, meanwhile, has spent the time in which his friends have squandered their own reputations keeping quiet and, for that matter, only taking a slight dent to his productivity compared to the last decade or so of his life.

But even if he’s avoided sticking his foot in it, he remains fundamentally a technophilic humanist. He admirably had more of an environmentalist streak than many in his cohort and wasn’t nearly as invested in utopianism as many, finding more of interest in computers than space travel.…

It’s November 26th, 1977. Between now and December 17th, an airplane carrying the University of Evansville basketball team will crash, killing the entire team, another plane crash at Madeira Airport in Portugal kills a hundred and thirty-one, and sex worker Marilyn Moore is injured in an attack by the Yorkshire Ripper. Despite the relative paucity of major disasters, the world still creeps ever closer to the eschaton and The Sun Makers airs.

It’s November 26th, 1977. Between now and December 17th, an airplane carrying the University of Evansville basketball team will crash, killing the entire team, another plane crash at Madeira Airport in Portugal kills a hundred and thirty-one, and sex worker Marilyn Moore is injured in an attack by the Yorkshire Ripper. Despite the relative paucity of major disasters, the world still creeps ever closer to the eschaton and The Sun Makers airs. It is impossible to talk about The Deadly Assassin without getting into the weeds of Doctor Who continuity, a sentence that is arguably the most depressing thing yet written in this project. Phil Sandifer manages to belch forth nearly 13,000 words of typically fanciful speculation (although at least this time he manages to avoid anything quite so masturbatorily pat as “the Doctor is from the Land of Fiction,” a critical conclusion so sickeningly self-congratulatory that it’s no wonder its author has disappeared off the face of the Internet and indeed the planet), but he’s hardly alone. Vast swaths of what Doctor Who gets up to when its worst instincts are indulged—waffle about the Eye of Harmony, Rassilon, Shabogans, and indeed Gallifreyan lore in general—all find their origin point here.

It is impossible to talk about The Deadly Assassin without getting into the weeds of Doctor Who continuity, a sentence that is arguably the most depressing thing yet written in this project. Phil Sandifer manages to belch forth nearly 13,000 words of typically fanciful speculation (although at least this time he manages to avoid anything quite so masturbatorily pat as “the Doctor is from the Land of Fiction,” a critical conclusion so sickeningly self-congratulatory that it’s no wonder its author has disappeared off the face of the Internet and indeed the planet), but he’s hardly alone. Vast swaths of what Doctor Who gets up to when its worst instincts are indulged—waffle about the Eye of Harmony, Rassilon, Shabogans, and indeed Gallifreyan lore in general—all find their origin point here. It’s October 25th, 1975. Between now and November 15th

It’s October 25th, 1975. Between now and November 15th It’s January 25th, 1975. Between now and February 15th, Edward Wilson and Robert McCullough will both die in attacks in Belfast, Clyde Hay will be the final viction of the Skid Row Slasher, a hundred and three civilians will be slaughtered by Ethiopian troops in Woki Duba, and two thousand and forty one will die in an earthquake in China. In addition, CEO of United Brands (formerly United Fruit) Eli M. Black will commit suicide shortly before it emerges that he paid a large bribe to the President of Honduras, P.G. Wodehouse will die of a heart attack in a hospital in Long Island, and Richard Ratsimandrava, the recently installed President of Madagascar, will be assassinated, sparking a civil war. Also, the world will slide ever closer to the eschaton, and The Ark in Space will air.

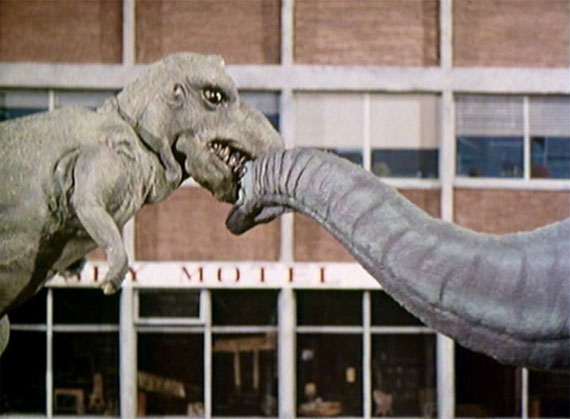

It’s January 25th, 1975. Between now and February 15th, Edward Wilson and Robert McCullough will both die in attacks in Belfast, Clyde Hay will be the final viction of the Skid Row Slasher, a hundred and three civilians will be slaughtered by Ethiopian troops in Woki Duba, and two thousand and forty one will die in an earthquake in China. In addition, CEO of United Brands (formerly United Fruit) Eli M. Black will commit suicide shortly before it emerges that he paid a large bribe to the President of Honduras, P.G. Wodehouse will die of a heart attack in a hospital in Long Island, and Richard Ratsimandrava, the recently installed President of Madagascar, will be assassinated, sparking a civil war. Also, the world will slide ever closer to the eschaton, and The Ark in Space will air. It’s January 12th, 1974. Between now and February 16th, twelve people will die in an IRA bmombing of a coach bus on the M62, and a hundred and seventy three people will die in a fire in Sāo Paulo. The implementation of the three-day week will cause massive economic strain on the United Kingdom, which does not directly kill anybody, but is linked to large spikes in crime and mental illness. In addition, Batman creator Bill Finger will die of a heart attack and movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn will die of old age. Beyond that, the world moves ever closer to the eschaton and Invasion of the Dinosaurs airs on the BBC.

It’s January 12th, 1974. Between now and February 16th, twelve people will die in an IRA bmombing of a coach bus on the M62, and a hundred and seventy three people will die in a fire in Sāo Paulo. The implementation of the three-day week will cause massive economic strain on the United Kingdom, which does not directly kill anybody, but is linked to large spikes in crime and mental illness. In addition, Batman creator Bill Finger will die of a heart attack and movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn will die of old age. Beyond that, the world moves ever closer to the eschaton and Invasion of the Dinosaurs airs on the BBC. It’s May 19th, 1973. Between now and June 23rd, forty-eight will die in a plane crash in India, six will die in a pair of IRA bombings in Coleraine, thirteen will die in Argentina when snipers open fire on protesters in the Ezeiza massacre, and six year old boy in Kingston upon Hull will die in the first fire of Peter Dinsdale’s near decade-long spree of arson. This relatively sparse major death toll masks the steady progression of the world towards the eschaton. Also, The Green Death airs.

It’s May 19th, 1973. Between now and June 23rd, forty-eight will die in a plane crash in India, six will die in a pair of IRA bombings in Coleraine, thirteen will die in Argentina when snipers open fire on protesters in the Ezeiza massacre, and six year old boy in Kingston upon Hull will die in the first fire of Peter Dinsdale’s near decade-long spree of arson. This relatively sparse major death toll masks the steady progression of the world towards the eschaton. Also, The Green Death airs. It’s February 26th, 1972. Between now and April 1st, 125 will die in a coal sludge spill in West Virginia, 19 will die in an avalanche on Mount Fuji, and the Easter Offensive wll begin in the Vietnam War, lasting into Octoer and resulting in somewhere between fifty and a hundred thousand deaths. In addition, M.C. Escher will die in a hospital in the Netherlands, the world will inch ever closer to the eschaton, and The Sea Devils will air.

It’s February 26th, 1972. Between now and April 1st, 125 will die in a coal sludge spill in West Virginia, 19 will die in an avalanche on Mount Fuji, and the Easter Offensive wll begin in the Vietnam War, lasting into Octoer and resulting in somewhere between fifty and a hundred thousand deaths. In addition, M.C. Escher will die in a hospital in the Netherlands, the world will inch ever closer to the eschaton, and The Sea Devils will air. The rule, apparently, is that anyone talking seriously about this story has to start with Paul Cornell’s 1993 review of it. I’m not entirely sure why this is the rule—presumably because Cornell is surely terribly embarrassed by the review now that he’s firmly into the “everything is lovely, especially fandom and the Pertwee era, let’s all just get along and support New Labour” phase of his career instead of the “actually doing anything worthwhile” one. Or perhaps just because, in spite of Cornell’s latter day shame at having ever had interesting opinions, the review remains one of the most solid and important things ever said about the Pertwee era. It’s not that Cornell is correct per se—his vituperative denunciations of the entire cast along with everyone else involved in the story is excessive, not least in his claim that there are only two competent actors in the era, which more than doubles the actual number, although he at least correctly identifies one of them. It’s just that it’s petty, mean-spirited, and therefore exactly what the era needs, culminating in the utterly savage kicker that Barry Letts and Terrence Dicks “exiled the Doctor to Earth and made him a Tory.”

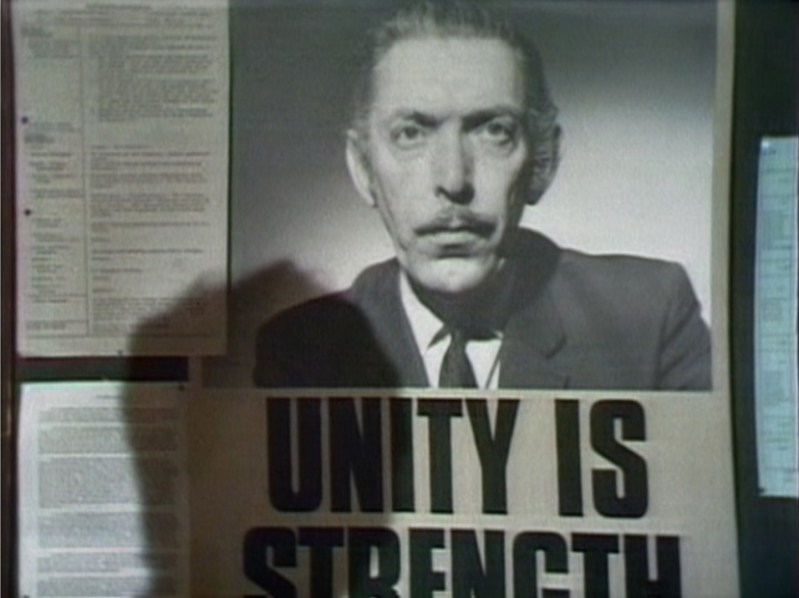

The rule, apparently, is that anyone talking seriously about this story has to start with Paul Cornell’s 1993 review of it. I’m not entirely sure why this is the rule—presumably because Cornell is surely terribly embarrassed by the review now that he’s firmly into the “everything is lovely, especially fandom and the Pertwee era, let’s all just get along and support New Labour” phase of his career instead of the “actually doing anything worthwhile” one. Or perhaps just because, in spite of Cornell’s latter day shame at having ever had interesting opinions, the review remains one of the most solid and important things ever said about the Pertwee era. It’s not that Cornell is correct per se—his vituperative denunciations of the entire cast along with everyone else involved in the story is excessive, not least in his claim that there are only two competent actors in the era, which more than doubles the actual number, although he at least correctly identifies one of them. It’s just that it’s petty, mean-spirited, and therefore exactly what the era needs, culminating in the utterly savage kicker that Barry Letts and Terrence Dicks “exiled the Doctor to Earth and made him a Tory.” It’s May 9th, 1970. Between now and June 20th, Henry Marrow will be killed in North Carolina in a racist hate crime, two will die when police fire into a crowd at a demonstration at Jackson State University, a fourteen-year old fan will die after being struck in the head by a foul ball at a Major League Baseball game, eleven will die in Israel in a Palestinian terrorist attack, six when a plane crashes into an Interstate Highway in Florida. In addition, E.M. Forster will die of a stroke, Abraham Maslow will die of a heart attack, and unnumbered people will die in the ongoing Vietnam War whilst the world slides ever closer to the eschaton. Also, Inferno airs.

It’s May 9th, 1970. Between now and June 20th, Henry Marrow will be killed in North Carolina in a racist hate crime, two will die when police fire into a crowd at a demonstration at Jackson State University, a fourteen-year old fan will die after being struck in the head by a foul ball at a Major League Baseball game, eleven will die in Israel in a Palestinian terrorist attack, six when a plane crashes into an Interstate Highway in Florida. In addition, E.M. Forster will die of a stroke, Abraham Maslow will die of a heart attack, and unnumbered people will die in the ongoing Vietnam War whilst the world slides ever closer to the eschaton. Also, Inferno airs.