Ending Explained (Part 4)

Final part of a consideration of John Carpenter’s In The Mouth of Madness (1994). The ideas in this essay were partly developed in conversation with Elliot Chapman and George Daniel Lea.

In The Mouth of Madness, H.P. Lovecraft, Alan Moore’s Providence, metafiction, the ‘fourth wall’, China Miéville’s ‘arche-fossil’, and the Marxian ‘real abstraction’.

*

In the graphic novel Providence, written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Jacen Burrows, H.P. Lovecraft is bred to be a redeemer or messiah by a secret society or cult whose aim is nothing less than the rupturing of the division between reality and fiction to permit the re-entry into reality of the Old Ones, the Old Gods, the Outer Monstrosities, the presiding cosmic entities of the haute Weird. In an early twentieth century America which seems to partly be the world in which Robert Chambers sets The Repairer of Reputations (first story in The King in Yellow), closeted gay journalist Robert Black makes a tour of lovecraftian events and characters which represent the activities of the cult – events and characters which directly mirror and reiterate events and characters we know from Lovecraft stories. He meets H.P. Lovecraft, who listens to his tales and reads the material he has amassed. Lovecraft then turns this material into his own fiction. Mirroring the rise of Lovecraft as a massively freighted cultural touchstone in the real world, Lovecraft’s fiction then goes on to reach a critical mass of critical appreciation and cultural belief, which triggers the apocalypse desired and engineered by the cult. As a result of a concentration of semiotic hegemony and cultural influence, Lovecraft’s fiction comes into being. Lovecraft’s fiction, and his cultural footprint, thus becomes a conduit for outside entities who take over humanity’s collective consciousness, bringing our nightmares into reality. The Old One entities are depicted as a kind of corporate cloud of sentience which, via its human representatives among the cultists, wants and engineers this turn of events.

In the graphic novel Providence, written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Jacen Burrows, H.P. Lovecraft is bred to be a redeemer or messiah by a secret society or cult whose aim is nothing less than the rupturing of the division between reality and fiction to permit the re-entry into reality of the Old Ones, the Old Gods, the Outer Monstrosities, the presiding cosmic entities of the haute Weird. In an early twentieth century America which seems to partly be the world in which Robert Chambers sets The Repairer of Reputations (first story in The King in Yellow), closeted gay journalist Robert Black makes a tour of lovecraftian events and characters which represent the activities of the cult – events and characters which directly mirror and reiterate events and characters we know from Lovecraft stories. He meets H.P. Lovecraft, who listens to his tales and reads the material he has amassed. Lovecraft then turns this material into his own fiction. Mirroring the rise of Lovecraft as a massively freighted cultural touchstone in the real world, Lovecraft’s fiction then goes on to reach a critical mass of critical appreciation and cultural belief, which triggers the apocalypse desired and engineered by the cult. As a result of a concentration of semiotic hegemony and cultural influence, Lovecraft’s fiction comes into being. Lovecraft’s fiction, and his cultural footprint, thus becomes a conduit for outside entities who take over humanity’s collective consciousness, bringing our nightmares into reality. The Old One entities are depicted as a kind of corporate cloud of sentience which, via its human representatives among the cultists, wants and engineers this turn of events.

I am not in a position to engage in responsible criticism of Providence itself, having only read it once – and that a few years ago – but it seems to owe something to John Carpenter’s 1994 movie In The Mouth of Madness, or at least to be mining a startlingly similar seam, albeit with a more dense, literary, and specifically referential (though not reverential) approach to Lovecraft in particular.

Moore has the advantage of being able to consider the recent extraordinary upsurge of interest in Lovecraft, and the history of Lovecraft’s growing bottom-up success which fed into it, even as he – Moore – contributes to it, enfolding his own consideration into the phenomenon he is thinking about and vice versa.

One of the things about John Carpenter as an artist is that he sometimes seems almost uncannily ‘of his moment’ but also intensely prescient of forthcoming cultural preoccupations. As with Halloween, The Thing, and They Live!, with In The Mouth of Madness, Carpenter was well ahead of the curve. …

In a key, early scene, Trent is walking through the city at night. He looks at urban walls covered in posters for Cane’s books; these posters are tattered yet omnipresent. …

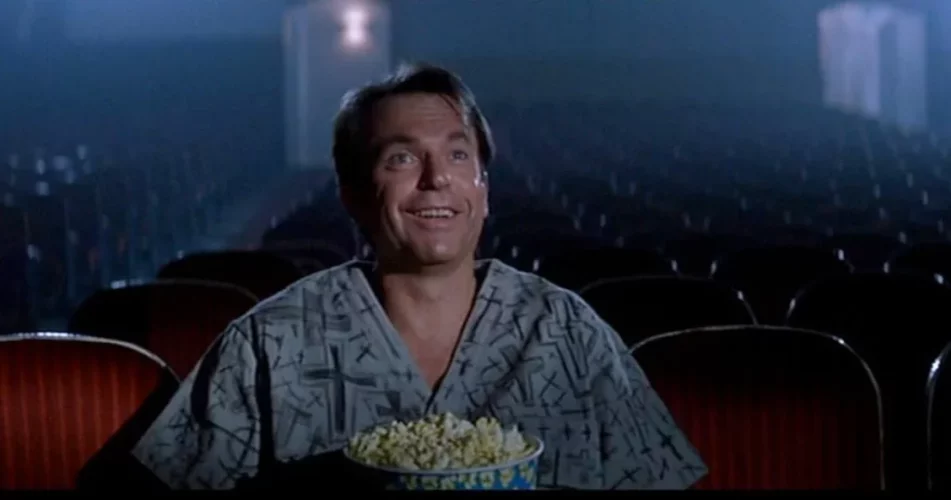

In a key, early scene, Trent is walking through the city at night. He looks at urban walls covered in posters for Cane’s books; these posters are tattered yet omnipresent. … John Carpenter’s late – and last – classic In the Mouth of Madness (1994) is famously metafictional. In the final scene of the film, the ‘protagonist’ John Generic Name… sorry, I mean John Trent… goes into a cinema which is showing a film called In the Mouth of Madness, advertised as starring John Trent, and watches himself on the screen, watches the film we’ve just seen, essentially. He watches himself declaring repeatedly (in alternate cuts of the same scene, featuring Sam Neill’s varying line deliveries) that he is nobody’s puppet and that the surreal things he’s experiencing are “not reality”. Apparently overcome by the realisation that he is, in fact, a fictional character in a film, John Trent begins laughing. His laughter gradually goes from being hysterical in the figurative sense to hysterical in the literal sense. As he starts having a panic attack, the film – the one we are watching – cuts to the credits.

John Carpenter’s late – and last – classic In the Mouth of Madness (1994) is famously metafictional. In the final scene of the film, the ‘protagonist’ John Generic Name… sorry, I mean John Trent… goes into a cinema which is showing a film called In the Mouth of Madness, advertised as starring John Trent, and watches himself on the screen, watches the film we’ve just seen, essentially. He watches himself declaring repeatedly (in alternate cuts of the same scene, featuring Sam Neill’s varying line deliveries) that he is nobody’s puppet and that the surreal things he’s experiencing are “not reality”. Apparently overcome by the realisation that he is, in fact, a fictional character in a film, John Trent begins laughing. His laughter gradually goes from being hysterical in the figurative sense to hysterical in the literal sense. As he starts having a panic attack, the film – the one we are watching – cuts to the credits. The Boy, a film from 2016, written by Stacey Menear and directed by William Brent Bell, has been largely-forgotten, but deserves better. It tries to be to patriarchy what Get Out, released the following year, would be to racism.

The Boy, a film from 2016, written by Stacey Menear and directed by William Brent Bell, has been largely-forgotten, but deserves better. It tries to be to patriarchy what Get Out, released the following year, would be to racism.