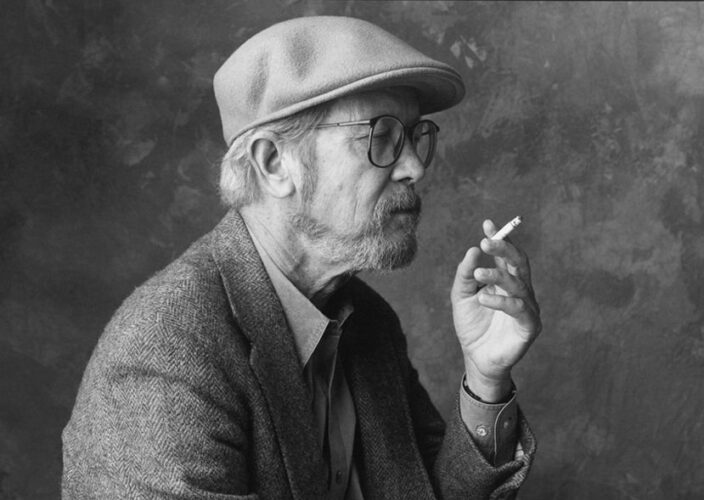

An Underwater Man (Book Three, Part 45: Elmore Leonard, Royal Blood)

Previously in Last War in Albion: Garth Ennis tore onto the American comics scene with an arc in which John Constantine gets lung cancer and pisses off the Devil.

“Day after fugitive day; footstep after shuffling footstep; heartbeat after anxious heartbeat, my enemies hunt me down. Down to the rocky bottom of this sunken city’s ruined heart. I am an underwater man.” – Jamie Delano, Hellblazer

This provides the cliffhanger into the final part of Dangerous Habits proper, in which Constantine’s scheme is revealed: he’s sold his soul to two other demons with whom the Devil (now named as “First of the Three,” eventually to simply become First of the Fallen in an effort to reconcile Ennis’s take on hell with what Gaiman had been doing in Sandman) is endlessly feuding, kept from open warfare by an extremely tenuous alliance, meaning that for anyone to claim it would start a war that would destabilize hell completely. And so the demons are left with no choice other than to keep him from dying. The issue ends with a splash page of Constantine gleefully showing all three of them the middle finger, wholly cured of cancer at their expense.

It is difficult to seriously contest the claim that this is the single most definitive moment for John Constantine as a character. It takes the core pleasure of the character—that he’s a cunning bastard one step ahead of everybody else—and puts it in a context that’s at once audacious and simple. “Selling your soul three times so the demons fight over it” is an eminently straightforward concept that explains itself, but cheating the Devil to cure your cancer is staggeringly gutsy. To pull off both at once while he flicks the demons off and says “up yours” is utterly perfect—a plot beat that literally anybody who is inclined to like John Constantine will enjoy.

Ennis followed the conclusion of Dangerous Habits with an epilogue issue in which Constantine runs into Kit, Brendan’s ex-girlfriend who he’d spent time setting up a few issues before. The effect of this is to set up a new and unusual status quo for Constantine, in which his life both has a bigger source of instability (in that he’s made a mortal enemy of the Devil) and a newfound anchor that made that instability more of a threat. Perhaps more to the point, however, it established a fundamentally delightful character; Kit was a no nonsense character who was at once unimpressed by Constantine and sympathetic to him. (As she explains over coffee following their reunion, “I used to watch you bullshitting loads of people and I had to admit, you were bloody good. I think you could have foxed me completely if you wanted to, but you didn’t. You always came to us because you wanted a break from all that, didn’t you?”)

It is clear, looking at Dangerous Habits, that Ennis was not merely a singular talent within the British Invasion but that he was operating from a fundamentally different set of influences than those more directly caught in the escalating Moore/Morrison dichotomy.…