A Sane and Rational Act (Book Three, Part 39: Discordianism, The Punisher)

Previously in The Last War in Albion: The conspiracy theories about the Pentagon that Morrison engaged with in Doom Patrol owed an obvious debt to the foundational text of Discordianism, the Principia Discordia.

“Then I was cast down. Back to a world of killers, rapists, psychos, perverts. A brand new evil every minute, spewed out as fast as men can think them up. A world where pitching a criminal dwarf off a skyscraper to tell his fellow scum you’re back is a sane and rational act.” – Garth Ennis, The Punisher

As the dates suggest, this was a work that emerged out of 1960s counterculture, beginning in the post-Beat tradition and fully blossoming in the wake of the hippies. (It will not escape attention that the 1970 edition was printed in San Francisco.) The whole business with the number twenty-three emerges from the former influence, specifically and inevitably from Burroughs. Robert Anton Wilson, writing in the Fortean Times in 1977, recalls talking to Burroughs and hearing a story about “a certain Captain Clark, around 1960 in Tangier, who once bragged that he had been sailing 23 years without an accident. That very day, Clark’s ship had an accident that killed him and everybody else aboard. Furthermore, while Burroughs was thinking about this crude example of the irony of the gods that evening, a bulletin on the radio announced the crash of an airliner in Florida, USA. The pilot was another captain Clark and the flight was Flight 23.” This led both Burroughs and Wilson (more about whom shortly) to begin collecting instances of the number twenty-three. This was, within the Principia Discordia, reframed as the Law of Fives, explained thusly:

POEE subscribes to the Law of Fives of Omar’s sect. And POEE also recognizes the Holy 23 (2+3=5) that is incorporated by Episkopos Dr. Mordecai Malignatius, KNS, into his Discordian sect, The Ancient Illuminated Seers of Bavaria.

The Law of Fives states simply that:

ALL THINGS HAPPEN IN FIVES, OR ARE DIVISIBLE BY OR ARE MULTIPLES OF FIVE,

OR ARE SOMEHOW DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY APPROPRIATE TO 5.

The Law of Fives is never wrong.

In the Erisian Archives is an old memo from Omar to Mal-2: “I find the Law of Fives to be more and more manifest the harder I look.”

Obviously there is no small quantity of joke here, especially in the final comment, which all but admits that all of this is a case of deliberately engineered apophenia. But this is in keeping with Discordianism, which is very much a satire of religion, albeit one that is typically engaged with in utter sincerity, both because that’s funnier and because a joke taken sincerely is an entirely credible vector for mystical experiences. And perhaps more to the point, because a religion based on the worship of Eris, the Grecian goddess of strife best known for kicking off the Trojan War cannot be entirely serious. Discordianism at its core is an emphatic and wholesale embrace of the trickster god, and its followers act precisely how you’d expect a bunch of post-hippie trickster god worshippers to act.

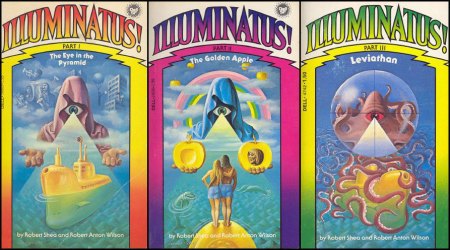

Among the more prominent Discordians was Robert Anton Wilson, who, along with Robert Shea felt that Discordianism would best advance if it had some sense of opposition, and so began creating a complicated myth about the Illuminati waging a longstanding war against the Discordians, the echoes of which could be found in, essentially, every conspiracy theory ever, all of which were completely and utterly true. Eventually this mythology grew to the point that Wilson and Shea decided to spin it off into a book, which became the Illuminatus! trilogy, a gonzo exploration of conspiracy theories and Discordian belief that became a countercultural classic. In 1976 a massive stage production of Illuminatus! was produced by Ken Campbell in the form of five individual plays each consisting of five twenty-three minute acts. On set design was Bill Drummond, who, after popping out to buy glue and never returning to the production became a musician and record producer, most famously of The Teardrop Explodes and Echo & the Bunnymen. In 1987 he joined with his friend Jimmy Cauty to form a hip hop band to be called the Justified Ancients of Mu-Mu, a title drawn from Illuminatus! In 1988 they scored an exceedingly cynical hit under the name The Timelords by creating a gloriously trashy mashup of the Doctor Who theme and various bits of glam rock.

Following this they reformed the group as the KLF and embarked on a series of legitimate dance hits including “What Time Is Love?” and “3 a.m. Eternal,” the latter of which hit number one the same week that Morrison’s Pentagon arc began. Across all of this their lyrics were sprinkled with Discordian references and 23 obsessions, pushing the iconography to its strangest and highest popular success. In 1992 the KLF and Extreme Nose Terror performed a stunningly aggressive version of “3 a.m. Eternal” at the BRIT awards, for which Drummond had to be persuaded not to chop his hand off with an axe on live TV and to settle merely for firing blanks at the crowd with an automatic weapon before an announcement that “KLF has left the music industry.” They subsequently dumped a dead sheep outside an afterparty and proceeded to retire entirely from the music industry to become an art collective, where they most famously burnt a million pounds cash on the Scottish island of Jura before embarking upon twenty-three years of inactivity.

Morrison would surely have been aware of all of this. They cited Illuminatus! alongside Moorcock on a list of their most influential books in 1999, and the effort needed to draw connections between the Pentagon arc of Doom Patrol and Illuminatus! is essentially nonexistent—the focus on the number five itself makes it implausible that Morrison didn’t have the Discordians in mind, But this was very much an arc more in line with Crawling From the Wreckage than the Brotherhood of Dada arc, which is to say that it is not written as a kids’ introduction to Discordianism. Nowhere are Wilson and Shea or the Principia Discordia mentioned or directly alluded to. More to the point, the worldview the comic offers is not really Discordian. The elements are there, but Morrison has remixed it into something that is very much their own unique mix of paranoid conspiracy theory, magical reality alteration, and occult symbolism. Nevertheless, the basic mixture of themes and iconography here is undoubtedly compelling, and indeed Morrison would return both to the Flex Mentallo idea and to the iconography of paranoid conspiracies and dark secrets beneath America with considerable effect later in their career.

Following the Pentagon arc, Morrison penned a one-off called “The Beard Hunter.” This was the first instance of a basic format Morrison would return to a few times across Doom Patrol in which they offered a parody or pastiche of other superhero comics within the structures of Doom Patrol. Other instances of this included Doom Patrol #53, which saw Morrison and artist Ken Steacy do an affectionate Jack Kirby pastiche, and the one-shot Doom Force, which reimagined the Doom Patrol as a parody of Rob Liefeld’s X-Force. In “The Beard Hunter,” meanwhile, Morrison took aim at the Punisher.

The Punisher originated as a Spider-Man villain in 1974. Created by Gerry Conway as a riff on Don Pendleton’s The Executioner books, which told the story of Vietnam veteran Mack Bolan’s one man war against the Mafia. The character initially served as an antagonist, recruited under false pretenses by the Jackal to kill the title character. These early stories typically served to portray the character as a bit of a hapless dupe—his first two appearances both see him fooled into thinking Spider-Man is a criminal and trying to kill him only to eventually change sides and aid him. An impressive costume design, however—an all black suit with a white skull across the chest, its teeth forming a belt—along with the basic “cool” of very large guns was enough to make the character compelling in spite of his somewhat flimsy role in the actual narrative.

In 1975 the character got his first solo adventure in the black and white Marvel Preview anthology. This was a somewhat drab noir story that sees the Punisher hunting an assassination ring, but it finally filled in the character’s origin. This did not turn out to be a nuanced thing, perhaps unsurprisingly given the lack of nuance implicit in “heavily armed vigilante wages a one man war on crime”; in short, the Punisher’s family was killed by criminals, and so he hunts and kills them himself. Another solo story in the one-off Marvel Super Action a few months later tried to flesh the character out further, but failed to take off, and he remained a supporting character in Spider-Man for the rest of the decade.

Come 1982 his star began to rise further as Frank Miller employed him for an arc during his Daredevil run. Perfectly positioned at the creative height of the run, with the character’s first appearance coming in the issue where the assassin Bullseye killed Daredevil’s girlfriend Elektra, the arc proved one of the most iconic takes on the character, and started to establish him as a more credible character in his own right. At the end of 1985 writer Steven Grant pitched a five issue miniseries starring the character to editor Carl Potts, who published it despite skepticism within the Marvel hierarchy. This proved well-timed, with the character ending up being Marvel’s nearest equivalent to The Dark Knight Returns, which launched the month after Grant’s miniseries wrapped up. The next year Marvel launched an ongoing series, debuting the same month as Watchmen #10, which proved a smash success—by the time Morrison got around to parodying it in Doom Patrol it was among Marvel’s top-selling books, and had been joined by a second title, Punisher War Journal. A third series, Punisher War Zone, and the three were further joined by the sporadically released Punisher Armory, an oversized book that consisted of nothing but pictures and descriptions of the Punisher’s guns.

For the most part the Punisher was an unsubtle festival of violence—among the most graceless and unsubtle instances of post-Watchmen pseudo-realism to be had, and thus an obvious target for Morrison’s poison pen. The handful of interesting runs with the character lay in the future—most obviously in 2001 when Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon successfully revamped the character by, essentially, portraying him as an American version of Judge Dredd. But so too did the events that would highlight just how jaw-droppingly toxic the character could be. In some ways these were foreshadowed by his heyday. Punisher War Zone, notably, was penned by Chuck Dixon, a right-wing writer who would go on to write comics for the openly neo-nazi outfit Arkhaven Comics. But Dixon also wrote some of the most popular Batman comics of the 90s, and his mere presence cannot be called a problem, even if it is a dark omen.

No, the real problem was simply what the underlying fantasies of the Punisher were. For all his target was initially framed as the Italian Mafia, he was still a fantasy about a literal war on crime in which military tactics were used to execute criminals without any sort of trial. Yes, many of his stories took a cautious view on this, with the idea of the Punisher as a bad guy given constant voice, but this was always, in the end, undermined by the basic fact that he was an incredibly popular and high-selling title character with three books. And eventually the character’s iconography went in the inevitable direction implied by this. This began in the 21st century, not long after Garth Ennis’s run, during the US invasion of Iraq, where the Punisher’s distinctive skull icon became a popular insignia among American troops. This started with Navy SEAL Team 3, whose sniper unit called themselves the Punishers and used the skull as an insignia and a means of intimidation, painting it on the walls of buildings. As the most famous member of this team, Chris Kyle, put it in his autobiography, “We spray-painted it on our Hummers and body armor, and our helmets and all our guns. We spray-painted it on every building or wall we could, We wanted people to know, We’re here and we want to fuck with you.”

From these starts the skull became more widely adopted by the right. In 2015 the skull began being adopted by supporters of the Blue Lives Matter movement, a counter to the Black Lives Matter movement that responded to calls for the police to stop killing unarmed black men. Its use in this context is unambiguously chilling—a clear and unequivocal endorsement and glorification of police violence. Perhaps the peak of this came in 2017 when police in Catlettsburg Kentucky (population 1856) painted the skull on their cars. In the face of understandable protest, police chief Cameron Logan insisted that the use of the logo of a vigilante killer who hunts criminals did not in fact mean that the police were out to kill people, proclaiming that this “didn’t cross my mind,” a statement that’s unbelievable even by the standards of shit cops say to the media. In light of this it’s hardly surprising that the same year the logo showed up at the Charlottesville Virginia Unite the Right rally in which neo-nazis attacked the city of Charlottesville, murdering counterprotester Heather Heyer. The Punisher is in no way the only comics character with a nasty political legacy but it is difficult to think of or indeed imagine one more straightforwardly toxic and destructive. [continued]

February 22, 2022 @ 5:38 am

More recently, The KLF returned from their 23 years of inactivity with a book called 2023 which — as far as I can tell, having read neither — is kind of serial-numbers-lightly-pencilled-over Illuminatus! fanfic, mixed with 1984.

I got it for my sister, who was a big fan of their music back in the day, but I’m not sure how aware of the Discordian side of things she was, and I keep forgetting to ask her what she made of it.

(Oh, and I’m prepared to bet that Ford Timelord does not approve of cop cars with Punisher symbols.)

February 22, 2022 @ 8:11 am

I was at that after-party. The sheep seemed funnier back then.

February 22, 2022 @ 6:43 pm

This one feels a little like a screen memory . . . was Grant never attached to the Illuminatus TV adaptation? What happened there?

February 23, 2022 @ 7:44 pm

AM: I’ve known Bill and Jimmy on and off for years, ever since they brought their film of the money-burning to show in my living room around twenty years ago. From what I hear, all of us were pretty much floored by John Higgs’ remarkable book.

https://web.archive.org/web/20010419142332/http://www.geocities.com/magicofalanmoore/quid/quid.html

February 24, 2022 @ 7:52 pm

Bizarre to me how this post swung from something sublime and deeply influential for me to a discussion of a character I have loathed for literally decades.

February 24, 2022 @ 11:43 pm

Yikes, I thought Chuck Dixon’s worst crime was writing mediocre DC comics.

March 2, 2022 @ 6:35 pm

When I read the mention of “The Executioner” I thought of James Glickenhaus’s Exterminator films and, sure enough, direct inspiration.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=92YNeYwYuQI

Gotta love the hair flip.

July 7, 2023 @ 12:00 pm

A very interesting chapter of the book. I generally like to read books and articles on military topics. By the way, I don’t know that there is an air base in Florida. I recently read an article on a military blog https://www.agmglobalvision.com/the-best-snipers-in-history about the best snipers in history. Very interesting