Curdled to Sea Foam (The Last War in Albion Part 33: The Reversible Man and Chrono-Cops)

This is the ninth of ten parts of Chapter Five of The Last War in Albion, covering Alan Moore’s work on Future Shocks for 2000 AD from 1980 to 1983. An ebook omnibus of all ten parts, sans images, is available in ebook form from Amazon, Amazon UK, and Smashwords for $2.99. If you enjoy the project, please consider buying a copy of the omnibus to help ensure its continuation.

Most of the comics discussed in this chapter are collected in The Complete Alan Moore Future Shocks.

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Alan Moore’s flagging middle period of short stories for IPC came to a fortuitous end with the introduction of the Time Twisters line of stories, which provided his work with a renewed energy.

Most of the comics discussed in this chapter are collected in The Complete Alan Moore Future Shocks.

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Alan Moore’s flagging middle period of short stories for IPC came to a fortuitous end with the introduction of the Time Twisters line of stories, which provided his work with a renewed energy.

The flood of animal emotions surging in the street. Present desires precipitated. Curdled to a sea foam. – Alan Moore, The Highbury Working

|

| Figure 247: The narrator of “The Reversible Man” sees his wife for the last time. (From “The Reversible Man,” written by Alan Moore, art by Mike White, in 2000 AD #308, 1983) |

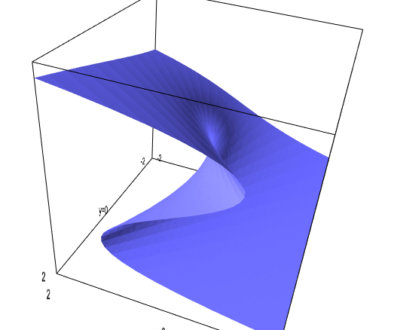

Moore has commented that “The Reversible Man” was “pathetically easy to write,” and that he was as a result surprised by its reception, speculating that its popularity was because “the events of our lives become dulled by reputation and it takes an unusual view of them for us to see life and its emotional implications anew,” disclaiming that the story’s success “had very little to do with me as a writer.” This is, perhaps, false modesty, however – elsewhere he proclaims it “one of the best stories I’ve ever done,” and boasts of how “during their lunch hour, the day that came out, it had all the secretaries weeping.” But even in that interview, where he breathlessly describes the emotional effect of how “an ordinary little scene of two people meeting, their first meeting… becomes their final departure,” he suggests that the story came mainly out of his inclination to “do something to see what will happen” and to experiment within the confines of the format.

The story may have been straightforward to write, but the suggestion that there is no writerly skill involved in its success is clearly untrue. Much of the story’s power comes not just from the way in which it frames the events of a man’s life, but in its specific choices of what events to frame and how to frame them. For instance, when the narrator’s father is dug up and brought to the hospital and eventually goes home, the narrator’s mother, understandably, moves out to live with her newly un-dead husband. The narration describes how “they took several of our things with them to furnish their home. Mostly antique furniture. We didn’t mind.” The choice of the furniture as a detail for this reversed event – the death of the narrator’s father – is a carefully chosen one. There are many things that accompany the death of a parent, but the choice of a mundane, material thing like dealing with their old furniture is a well-chosen one, such that the word “antiques” speaks volumes. Similarly, the description of how “work got progressively easier and I had to give less and less money to the firm every Friday night” is not the only way that one could describe reversing one’s career path, but it’s a particularly sharp one, preserving the sense of frustrating drudgery even in reverse.

More to the point, Moore’s claim that The Reversible Man was “a classic example of one of those stories that just lie around waiting for someone to trip over them and commit them to paper” overlooks the fact that he is neither the first nor the last writer to tackle this basic idea. In 1922 F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote a similar story in “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” and mentioned in the introduction that after writing the story he saw a similar idea in Samuel Butler’s notebooks. This is a reference to some notes Bulter wrote for his 1872 novel Erewhon (which is widely considered the first work to think seriously about the possibility of artificial intelligence), where he suggested that the people of Erewhon might “live their lives backwards, beginning, as old men and women, with little more knowledge of the past than we have of the future, and foreseeing the future about as clearly as we see the past, winding up by entering into the womb as though being buried. But delicacy forbids me to pursue this subject further: the upshot is that it comes to much the same thing, provided one is used to it.” The idea also appears in T.H. White’s revisioning of Arthurian legend The Once and Future King, first published in 1938, in which Merlin lives backwards in time. And after Moore the idea had life as well – Martin Amis won a Man Booker Prize in 1991 with Time’s Arrow, a novel that uses the same basic premise. And, of course, there are the films Memento and Irréversible, which tell their narratives backwards, even though the characters do not experience them that way.

|

| Figure 249: Backwards time is not the only significant theme that both Amis and Moore have written on. |

All of this points to the fact that Moore’s story works not just because he executed a reasonably common idea, but because he did it well. Likewise, Martin Amis didn’t get nominated for a Booker Prize for nicking an obscure old idea out of a boys comics magazine, but because he chose as the subject for his backwards life a doctor who worked at Auschwitz, describing how he helped create a race, the Jews, first creating their bodies in ovens, then animating them in fake showers, from which he personally removes the Zyklon B pellets, and then finally, for many, perfecting their dental work, giving freely from their own personal supplies of gold to craft fillings for them. “I knew my gold had a sacred efficacy,” the narrator enthuses. “All those years I amassed it, and polished it with my mind: for the Jews’ teeth.” This shocking inversion of the Holocaust, where all of the degradations and atrocities become acts of life-giving kindness, gives it new power to horrify by creating a new and startlingly perverse perspective to look at them, much as Moore inverts the major events of life to fill them with new poignancy. The suggestion that this potency comes merely from the idea and not the particulars of the execution is demonstrably false.

|

| Figure 250: One of the most stunningly bleak panels in Moore’s early career (From “One Christmas During Eternity,” written by Alan Moore, art by Redondo, in 2000 AD #271, 1982) |

But the power of “The Reversible Man” is also worth looking at in context with another fact: it is only the second short story Moore wrote for 2000 AD that cannot be described as a comedy. In the previous two-and-a-half years of writing strips for the magazine, the only other time he did something decisively non-comedic came in July of 1982, when he penned “One Christmas During Eternity” – a bleak number about a family of immortals celebrating Christmas with their son, in which it turns out that the son is a robot they rented for the day and had to return, and that they do not even get the same robot year-to-year – in Prog 271. Both stories are elevated by the fact that they have ambitions beyond merely demonstrating a clever idea. “The Reversible Man” does not merely stand out in contrast to the rest of Moore’s short stories, though – its quiet poignancy marks it out from the rest of 2000 AD. In Prog 308 the other stories were: a story in which an alien barely survives a crash landing, with a final panel revealing the strip’s punchline – the alien has landed in Birmingham; a Judge Dredd story featuring the Prankster, who commits elaborate and destructive practical jokes; the first installment of Invasion of the Thrill-Snatchers, in which the Greater Spotted Thrill-Sucker is lured to Earth to do battle with Tharg the Mighty; and the seventeenth part of a Rogue Trooper storyline called Fort Neuro, in which Rogue has to help defend a base of insane soldiers. All of these stories foreground action and comedy in a way that makes Moore’s story of ordinary human life stand out sharply.

Two issues after “The Reversible Man” Moore penned what he later considered to be his favorite Time Twister, “Chrono-Cops.” The sixth and final of his IPC collaborations with Dave Gibbons, “Chrono-Cops” is in many ways the most Alan Mooreish of his 2000 AD strips. Moore has always been a writer with a keen focus on questions of structure, and what Grant Morrison describes as his “love of obvious structure” is a thread that extends all the way to his hyper-elaborate games with the idea of the comics page in work like Promethea. “Chrono-Cops” can only be read in this context – in just five pages Moore constructs an elaborate farce of intersecting timelines in which characters repeatedly bump into their future and past selves and causes follow effects in a convoluted comedy of errors.

The plot is, by design, a mouthful. Joe Saturday and his partner, Ed Thursday, are police officers dealing with crimes against the timeline. On their way back from busting a perp for “the attempted murder of your own great grandfather” they encounter themselves about to leave on that very assignment. On their way to their next assignment, accordingly, they meet themselves going back, and are warned that on that assignment Ed will receive a black eye, and it’s suggested that they go pick up some raw steak before setting out. Doing so, they encounter a temporal car crash on the 1997 flyover (presumably related to The Highbury Working), where Ed is assaulted by Zanzibar Z. Ziggurat, who punches him in the face while proclaiming that he’s “never forgotten what you did to me” and that he should “wait till you find out what happens to your career!”

A deeply shaken Ed holds the steak to his black eye in the canteen as his earlier self buys it in the background before heading off on another mission (after inadvertently intersecting themselves warning themselves about the black eye, which they handle by hiding in the bushes). On this mission they are attempting to apprehend Yolanda Y. Yorty, a “long-term interest bandit” who would “deposit a pound note in her bank account, jump three hundred years into the future, and collect the accumulated interest.” The easiest way to apprehend Yorty turns out to be to arrest her as an infant, but a shaken Ed grabs the wrong baby, inadvertently accosting an infant Zanzibar Ziggurat, thus causing Ziggurat’s trauma that resulted in his earlier assault of Ed. At this point the stress proves to be too much for Ed, and he attempts to travel back in time and marry his own grandmother. Joe Saturday is tasked with bringing the rogue Chrono-Cop in, and ends up marrying Ed’s grandmother himself and thus becoming Ed’s grandfather. “Funny how things worked out,” Saturday reflects, while acknowledging that “Ed didn’t think it was funny. He gets out in four more years… he says he’s gonna kill me.”

By the larger standards of baroque time travel plots this is not a massive headscratcher, but for a five page story Moore works in an impressive amount of depth. He’s aided, of course, by Gibbons, whose attention to detail and clean artwork communicates with a clarity that enables Moore’s intricately worked plot to come across straightforwardly despite its complexity. Gibbons also imbues the story with a strong sense of cartooning-based comedy. Joe Saturday and Ed Tuesday are given clear and distinct visual designs so that they’re always immediately recognizable, and Gibbons puts considerable thought into the design of the minor characters so that even a largely insubstantial character like the guy they arrest on the first page are detailed, lush creations.

But in the end the story’s success is largely down to Moore. He is hardly the only person ever to write a time travel farce, but the decision to wed that farce to a parody of Dragnet-style cop story is fresh and innovative. The story isn’t just well-done, it’s inventive and alluring, combining elements that, on the surface, don’t go together into a coherent package. The strip is densely packed with both comedy and complexity, in a way that makes it stand out from the rest of what 2000 AD was doing.

But it would be a mistake to suggest that the arrival of the Time Twisters banner marked some absolute turning point for Moore’s 2000 AD work. Yes, “The Reversible Man” and “Chrono-Cops” are each strong contenders for being considered the best of Moore’s short pieces for the magazine, but it is not as though his post-Skizz work is universally brilliant. Sandwiched in between “The Reversible Man” and “Chrono-Cops” in Prog 309, for instance, is an untitled Time Twister in which aliens set up a Historical Zoo on a desolate and abandoned Earth, featuring reconstructions of historical Earth figures. Out of curiosity the aliens construct two copies of Albert Einstein “to see if they were smart enough to work out what had happened to them. You know… being dead and then being alive again.” They are, as it happens, and so go off to liberate the humans in the Military Enclosure, at which point the humans drive the aliens away and retake their planet. It is, to say the least, not one of Moore’s most impressive outings.

|

| Figure 253: Redondo’s heavy use of blacks and erratic linework give “Ring Road” a surreal and unsettling quality. (From “Ring Road,” written by Alan Moore, art by Redondo, in 2000 AD #320, 1983) |

On the other hand, the final six months of Moore’s short story writing do contain a cluster of quality stories not really seen since the impressive 1981 run from “Grawks Bearing Gifts” through “A Cautionary Fable.” In addition to “The Reversible Man” and “Chrono-Cops” there’s “The Big Clock,” the first DR & Quinch story (a Time Twister, much as the first Abelard Snazz was in fact a Ro-Jaws Robo-Tale), “Ring Road,” “Eureka,” and the sublimely bleak “The Time Machine.” All of these are solid – even the weakest of them, “Ring Road,” is strangely moody piece, with art by Jesus Redondo, a Spanish artist and 2000 AD standard. Redondo’s characters have what Moore describes as “dark emotional realism” and “a sort of sleazy credibility,” an effect generated by his propensity for heavily shaded pannels with large patches of black and a wealth of scratchy hatching. This serves as a good fit for the most literally elliptical of Moore’s stories, which features an escaped criminal violently hijacking a car and driving off, not realizing that she is driving through time. She starts in 1935, and winds her way past a 1950s diner, picks up a hippie hitchhiker, and passes some angry punks before seeing the flash of atomic armageddon and driving through a post-apocalyptic wasteland. From there she circles back to pre-historic times before finally pulling up to help a young girl standing by the roadside who is, of course, her younger self from the start of the story. It’s a straightforward twist ending story, but Redondo’s grim linework elevates it.

|

| Figure 254: It becomes obvious that Harry Bentley’s time machine is better described as his death. (From “Time Machine,” written by Alan Moore, art by Redondo, in 2000 AD #324, 1983) |

Redondo is also on hand four issues later for “The Time Machine,” which is easily the most depressing story Moore wrote for 2000 AD. It begins with a man, Harry Bentley, who is falling through a “freezing black,” that is “cold and crushing like interstellar space, without light, without stars,” but is unphased by it due to his sheer joy that his time machine worked. Over the next few pages he revisits moments in his life, going through all the regrets and sorrow of his past – losing Duffo, his stuffed clown, and failing to kiss Jackie Rutherford when he had the chance. Then the reader learns about his failed marriage, which came apart under financial strain and his obsession with building a time machine to get back to what he remembered as a happier childhood. And then, at the end, it’s revealed that the time machine never worked, and that he has thrown himself off a bridge in despair, and the functioning time machine is in fact his life flashing before his eyes as he drowns in Redondo’s river of sweeping black ink. [continued]

February 27, 2014 @ 8:24 am

Pedant point: Time's Arrow, by Amis, was nominated for the Booker (sic – not the Man Booker at the time) but lost to Okri's Famished Road.

February 27, 2014 @ 9:11 am

Looking at the extracts from the Reversible Man, it seems to me that an obvious trick is that the narrator has no decision making powers – his memory works forward, but he doesn't have the corresponding backwards hopes and fears. As a result he's presented as tramelled along his timeline with no real agency, a spectator of his apparently conventional life. Something that might have felt like a reasonable symbol of real experience to a young man in Thatcher's Britain.

February 27, 2014 @ 9:51 am

Following the Parenthesis That Would Not Die, I hesitate to assume anything isn't a stylistic choice, but I notice the part number is missing and there's no opening quote.

February 27, 2014 @ 11:26 am

Ah, that also helps explain why this didn't post on time – Blogger didn't save my last couple of edits to the post, including putting those in.

February 27, 2014 @ 11:26 am

Pedantry accepted. Thanks.

February 27, 2014 @ 2:47 pm

…how do you mention Time's Arrow and not mention its most-immediate predecessor and influence, the backwards war film from Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five?

For the record, this is it:

"Billy looked at the clock on the gas stove. He had an hour to kill before the saucer came. He went into the living room, swinging the bottle like a dinner bell, turned on the television. He came slightly unstuck in time, saw the late movie backwards, then forwards again. It was a movie about American bombers in the Second World War and the gallant men who flew them. Seen backwards by Billy, the story went like this:

American planes, full of holes and wounded men and corpses took off backwards from an airfield in England. Over France a few German fighter planes flew at them backwards, sucked bullets and shell fragments from some of the planes and crewmen. They did the same for wrecked American bombers on the ground, and those planes flew up backwards to join the formation.

The formation flew backwards over a German city that was in flames. The bombers opened their bomb bay doors, exerted a miraculous magnetism which shrunk the fires, gathered them into cylindrical steel containers, and lifted the containers into the bellies of the planes. The containers were stored neatly in racks. The Germans below had miraculous devices of their own, which were long steel tubes. They used them to suck more fragments from the crewmen and planes. But there were still a few wounded Americans, though, and some of the bombers were in bad repair. Over France, though, German fighters came up again, made everything and everybody as good as new.

When the bombers got back to their base, the steel cylinders were taken from the racks and shipped back to the United States of America, where factories were operating night and day, dismantling the cylinders, separating the dangerous contents into minerals. Touchingly, it was mainly women who did this work. The minerals were then shipped to specialists in remote areas. It was their business to put them into the ground, to hide them cleverly, so they would never hurt anybody ever again.

The American fliers turned in their uniforms, became high school kids. And Hitler turned into a baby, Billy Pilgrim supposed. That wasn't in the movie. Billy was extrapolating. Everybody turned into a baby, and all humanity, without exception, conspired biologically to produce two perfect people named Adam and Eve, he supposed.

Billy saw the war movies backwards then forwards-and then it was time to go out into his backyard to meet the flying saucer. Out he went, his blue and ivory feet crushing the wet salad of the lawn. He stopped, took a swig, of the dead champagne. It was like 7-Up. He would not raise his eyes to the sky, though he knew there was a flying saucer from Tralfamadore up there. He would see it soon enough, inside and out, and he would see, too, where it came from soon enough — soon enough."

February 27, 2014 @ 5:00 pm

Incidentally, the temporal car crash on the 1997 flyover in Chrono-Cops backs up all sorts of traffic, including the T.A.R.D.I.S. of the infamous Dr Who: http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_8ie37mgxIXA/RzqA9E-uypI/AAAAAAAACFY/bJW9GSCm3wY/s1600-h/cc2.jpg

February 28, 2014 @ 6:36 pm

In the 60s (I believe) there was an actual antiwar short movie (my mother recalled seeing it) that was just a backward sequence of bullets coming out of bodies and back into guns and then back into factories and so on.

February 28, 2014 @ 6:38 pm

Here's the entire thing, btw: http://www.againwiththecomics.com/2009/05/man-reversible-moores-alan.html

June 26, 2014 @ 11:51 am

You're missing something with Chrono-Cops because, while it is a parody of Dragnet, it is specifically a pastiche of Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder's parody of Dragnet, "Dragged Net!" in Mad #3: https://secure.flickr.com/photos/bartsol/6475127763/in/photostream/

As a Moore and Gibbons work that heavily relies on the EC style, it prefigures Watchmen in a number of ways.

February 17, 2015 @ 5:23 am

Great stuff. That story The Time Machine is quite sad and somehow beautiful and I really remember its impact on me as a kid.