|

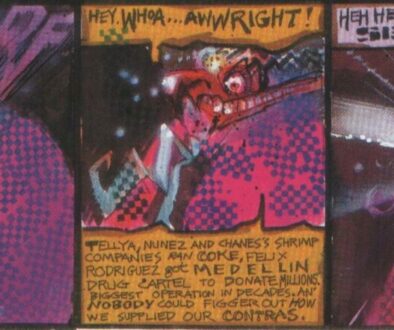

Figure 562: The explosion of the Houses of Parliament. (Written

by Alan Moore, art by David Lloyd, from “The Villain” in Warrior

#1, 1982) |

This leaves only Moore’s sixth and most audacious page. It opens with an extreme close-up on the man, so that only one slit eye of his mask and its painted black curl of an eyebrow is visible. He intones the aforementioned rhyme: “Remember, remember, the fifth of November, the Gunpowder Treason and plot. I know of no reason why the Gunpowder Treason,” he continues, and at once, at for any of the readership for whom the mere shape and visual of his outfit and mask was not sufficient to identify the character he is playing, he stands revealed as a man dressed in a Guy Fawkes costume. As he provides the final three iambs of his rhyme, “should ever be forgot,” the tacit promise of this costume is suddenly and triumphantly realized. The panel displays the man from behind, so that the audience looks over his shoulder towards the Houses of Parliament, which are in the midst of exploding. The remains of what was once the clock tower burst outwards, black fragments shattering against the white background of the explosion, the circles of the clock faces still implied in the negative space of the devastation. This is followed by another extremely narrow panel, showing the girl’s shocked reaction with a close-up of one bulging eye – notably the left one, where the man’s eye two panels earlier was the right, implicitly constructing a completed face framing the destruction of London’s single most iconic landmark. “The Houses of Parliament,” the girl exclaims. “Did you do that?”

|

Figure 563: The artist signs his work. (Written by Alan Moore, art by David

Lloyd, from “The Villain” in Warrior #1, 1982) |

“I did that,” the man replies simply. And as he does, the narrative captions return: “the rumble of the explosion has not yet died away as from far below comes the rattle of smaller reports. And suddenly the sky is alight with…” it trails off, and the trail of thought is continued by the girl, looking up joyfully at the sky and shouting, “fireworks! Real fireworks! Oh god, they’re so beautiful!” And they are – eleven cumshot explosions over the noir night, arranged in an eponymous V. The narration continues over a panel further subdivided into four narrow columns depicting Londoners staring at the spectacle. “And all over London,” it says, “windows are thrown open and faces lit with awe and wonder gaze at the omen scrawled in fire on the night.” A final panel shows the man and woman in silhouette. “There,” the man declares. “The overture is finished. Come. We must prepare for the first act.” “Me?? B-but… Oh. Okay,” the woman replies.” “It is precisely 12:07 A.M. It begins to rain,” the narration concludes. “To be continued,” reads the title card.

In just six pages, then, Moore introduces a dystopian future that is intensely grounded in the political reality of the time, introduces his two main characters, casts his lot with theatrical villains, and then blows up the Houses of Parliament. It is one of the most shocking and effective openings in comics, made even more impressive by the fact that the script was completed in July of 1981, at which point Moore’s published output consisted of Roscoe Moscow and the start of The Stars My Degradation for Sounds, two years worth of Maxwell the Magic Cat, a dozen short stories for 2000 AD, and some work in Doctor Who Weekly, none of which really suggested a writer capable of such an invigorating story.

|

Figure 564: Evey’s father is physically modeled on Alan Moore’s

good friend Steve Moore. (Written by Alan Moore, art by David

Lloyd, from “Victims” in Warrior #3, 1982) |

Ultimately, two things contribute to the sense of radicalism. The first is how well-grounded in the present of 1982 Britain V for Vendetta’s dystopia is. The basic suggestion that Britain could be less than fifteen years from a fascist takeover is fundamentally unsettling. When, in the third installment, Moore finally reveals the backstory of Britain as the girl, Evey, tells the masked man V her life story, setting the date as just a decade in the future, in 1992. It is true that the details were quickly discredited – the V for Vendetta timeline assumes a Labour victory in the next General Election, with the fascist government rising to power because the (presumably) Foot government made good on an election promise to remove nuclear missiles from British soil, resulting in them being the only country to survive a 1988 nuclear war. And yet for all that the some of the details were off, V for Vendetta was surprisingly prescient, most famously in its depressingly accurate prediction that by 1997 the streets of Britain would be lined with surveillance cameras to capture the population’s every move. Similarly significant is the decision to ground Evey’s past in the material reality of 1982. Evey grew up on Shooter’s Hill, in the South of London, the home, of course, of Moore’s friend and colleague Steve Moore, to whom Evey’s father bares a marked resemblance in the photo Evey shows V. V alludes to “the recession of the eighties” as history, but it was of course a current event to the readership. The result of all of this is that the world of V for Vendetta is, while not the reader’s own, inextricably connected to it – a world the reader is obliged, within the narrative, to treat as a serious cultural possibility.

The second factor, then, is the unwavering way in which the narrative takes seriously the idea that in the face of such a world, violent terrorism might be a reasonable action. Over time, this became one of the primary themes of V for Vendetta, with the final chapter, published by DC Comics, focusing heavily on the moral legitimacy of violence as a tactic. But in the early installments it is difficult to have anything but sympathy for V and his titular vendetta. Certainly the first installment, for all that its title explicitly proclaims V to be the villain of the piece, is firmly on his side. The movie posters of films in which the most memorable character is a villainous raving lunatic that adorn his Shadow Gallery make this clear, as, more bluntly, does the fact that the alternative to V, as presented in that installment, is a bunch of would-be rapists with badges. The thrilling denouement, blowing up Big Ben, is provocative, but it is clearly something the reader is meant to find thrilling. And it is thrilling, simply because Moore identifies an argument that is both tremendously compelling and yet widely treated as “improper” to speak aloud, namely that blowing shit up is, on the whole, a perfectly reasonable response to Thatcherism.

|

Figure 565: Dick Turpin was an 18th century highwayman

whose adventures became staples of British popular fiction. |

In this regard, as Moore is quick to admit, he is slotting into a grand British “tradition of making heroes out of criminals or people who in other centuries might have been regarded as terrorists.” Elsewhere, he notes that this tradition “goes back to Robin Hood, Charlie Peace, and Dick Turpin. All of these British criminals that actually are treated as heroes.” The sentiment, it’s clear, was shared by David Lloyd, whose suggestion it was to model the protagonist on Guy Fawkes, suggesting that this would “look really bizarre and it would give Guy Fawkes the image he’s deserved all these years. We shouldn’t burn the chap every Nov. 5th but celebrate his attempt to blow up Parliament!” Moore, for his part, claims that, upon receiving this suggestion, “two things occurred to me. Firstly, Dave was obviously a lot less sane than I’d hitherto believed him to be, and secondly, this was the best idea I’d ever heard in my entire life.”

But Moore is also quick to point out, when asked whether V is a hero, that “we called the very first episode ‘The Villain’ because I thought there was an ambiguity there that I wanted to preserve,” and, when pushed in a 2012 interview, makes clear V’s violent tactics are “something I don’t sympathize with,” and that “of course” people should not actually go and blow up the Houses of Parliament, although he also notes that this is largely a plot point introduced in Book Three, and that the matter is left morally ambiguous prior to that point. That is not, however, to say that it isn’t addressed. Indeed, the ninth chapter of Book One is entitled “Violence,” and features as one of its central scenes Evey confronting V about the fact that he used her offer to help him to make her an accomplice to murder. V’s response is typically oblique – he points out that it was Evey who offered to help V, and cryptically quotes Thomas Pynchon’s V, but otherwise declines to engage with Evey’s moral dilemma. Evey, for her part, comes back to V later in the issue, and apologizes, admitting that she “was trying to get out of taking the blame,” but also emphatically declares that she won’t be involved in killing again, a vow V witnesses in utter silence.

|

Figure 566: Derek Almond abuses his wife. (Written by Alan Moore, art by David Lloyd,

from “Violence” in Warrior #9, 1983) |

But these two scenes are interspersed among several others also reflecting on the titular theme of the chapter. It opens with Eric Finch, the detective hunting V, going over autopsy results, beginning with a cold and clinical discussion of the physical manifestation of violence: “the wound’s been cleaned up a little, Eric,” Doctor Delia Surridge explains, “but you can see that it has a fairly ragged edge. So you’re right, it isn’t a knife wound. It looks like something’s been punched through the skin with incredible force.” Later, there is a scene between Derek Almond, the head of the Finger, and his wife Rose, which culminates in a scene of domestic violence as Derek hits Rose and screams at her that “I don’t have to take any of this crap from you! Not any of it!” And rounding out the issue is V finally coming for Dr. Surridge, who has been expecting him ever since Eric Finch gave her a rare rose that V had left at the scene of an earlier murder, and who has spent the issue remembering an image of a man, completely black in silhouette, framed by a massive fire behind him. When she realizes that V has come for her, she sits up in bed, and says, “it’s you isn’t it? You’ve come… you’ve come to kill me.” V confirms this, and Dr. Surridge breaks down, saying “Oh thank God. Thank God.”

|

Figure 567: Delia Surridge welcomes her imminent

death. (Written by Alan Moore, art by David

Lloyd, from “Violence” in Warrior #9, 1983) |

And so Evey’s non-debate with V over the use of violence is positioned in the context of a relative diversity of instances of violence. There is no easy and straightforward moral conclusion to be drawn from all of these scenes. The incident between the Almonds is clearly horrific, but the clinical and detached description of the dead Fingerman’s wounds at the outset and the subtleties implicit in Delia’s joyful embrace of her imminent demise are altogether more ambiguous. They are certainly not things the reader is meant to look upon as straightforwardly pleasurable, but they are also not easily read as condemnations of the very idea of violence. Yes, Moore eventually arrives at the position that violence is categorically unacceptable, but crucially, this takes place years after the strip started, and after Moore and Lloyd have moved the comic from being published in the UK to being published in the US. It is not fair to call it an unexpected plot development, but it is fair to say that the strip could have developed in other directions.

|

Figure 568: Alan Moore’s last use of caption boxes in V for Vendetta for anything

other than establishing settings was in the third installment. (Written by Alan Moore,

art by David Lloyd, from “Victims” in Warrior #3, 1982) |

But this is true of V for Vendetta in a more general case as well. The strip was conceived and the script for the first installment written in 1981, while the final installment didn’t see print until 1989. Any project would drift and evolve over that sort of time period, even before one considers the degree to which Moore’s career evolved over those eight years. Certainly the strip gradually grows more stylistically confident over time. Moore and Lloyd determined at the outset that they would keep narration to a minimum and entirely eliminate sound effects and thought bubbles. But Moore, in the early chapters, still uses narration for key events. But gradually he manages to eliminate them entirely, using them for the last time in the fourth installment, where he narrates the effect changing the person who delivers the periodic “Voice of Fate” broadcasts has on the British population. After that, Moore finds ways to communicate information by giving the role of narration to specific characters. From the beginning of his career Moore displayed an instinctive understanding of the way in which words and images could be used to provide two parallel streams of information, but this skill takes a visible leap forward in the seventh installment of V for Vendetta, “Virtue Victorious,” published in November of 1982, where he runs narration from the corrupt Bishop of Westminster as he prays before engaging in sexual relations with someone he believes to be a fifteen year old girl, but who is in fact an undercover Evey sent by V. “Dear God, thous who has granted us reprieve from thy final judgement, thou who has provided us with that most terrible warning, help us to be worthy of thy mercy,” the bishop intones, while the art shows events from an entirely different scene as V kills the bishop’s guards and makes his way to his window.

|

Figure 569: Moore juxtaposes the Bishop’s prayers

with V’s attack. (Written by Alan Moore, art by

David Lloyd, from “Virtue Victorious” in Warrior

#7, 1982) |

The effect is a common one in Moore’s repertoire, using the contrast between text and image to communicate things that neither can communicate on their own. But by November of 1982, the closest thing he had done to this sort of contrast was “The English/Phlondrutian Phrasebook” with Brendan McCarthy for 2000 AD, in which humorous sayings from a hypothetical tourist guidebook for an alien planet are juxtaposed with scenes from a nightmarish visit to said planet. But “Virtue Victorious” does not use its contrast for comedy, or, at least, not for any straightforward comedy, and the point is not the contrast between the bishop’s words and the images, but the way in which the two intersect and resemble each other. The bishop is praying for divine forgiveness for the child molestation he’s about to commit, but when he speaks of “the evil one who is surely come amongst us in this, the hour of our greatest trial,” the images of V fighting his way through the guards give clear double meaning to these words. [continued]

December 10, 2014 @ 2:53 am

eleven cumshot explosions

Suspect this is not the exact pyrotechnical industry jargon for that style.

December 10, 2014 @ 5:11 am

Ha. Yes, that particular description was a bit over-the-top, yet disturbingly effective. I am glad the Dr. Sandifer included the accompanying art, as the black & white image is evocative and triumphant. But nonetheless… ew.

December 10, 2014 @ 8:16 am

It is strange to me that Guy Fawkes should, entirely on the strength of this comic and the movie it spawned, be reimagined as some sort of anarcho-libertarian hero. The real Guy Fawkes did not object to government or even to oppressive government. He just thought Catholics should be the oppressers and Anglicans the oppressed instead of the other way around. It's also strange to note the smug contempt American Christians have for the religious strife among Muslim populations when it's really not that long ago that Protestant-Catholic conflicts were as bloody as anything in the Islamic world.

December 10, 2014 @ 9:56 am

I initially read "elven cumshot explosions" and it took me a couple seconds to process what was going on at the beginning of this post.

December 10, 2014 @ 10:39 am

The rare rose left by V and given by Finch to Surridge is a 'Violet Carson' named after the actor who played the sharp tongued old battleaxe Ena Sharples in long running soap Coronation St. (changed inexplicably in the film to 'Scarlet Carson' which loses the 'V' reference). My guess at the significance of this is that Ena was often written as the 'bad guy' of the show, representing small minded bigotry and stubborn bloody mindedness and yet became a national treasure. Which fits nicely into Moore's meditation on how the British love to validate their villains.

December 10, 2014 @ 10:50 am

I also remember some speculation in the letters pages of Warrior at the time as to the 'secret identity' of V (less sharp readers not realising that a traditional surprise reveal was not the game Moore was playing) and some wild guesses based on the black sillhouette and the "you're beautiful" line from Surridge that V for Vendetta was in fact to be a continuation of Marvelman and that V was actually either Mike Moran or Evelyn Creme.

December 10, 2014 @ 8:58 pm

Heh. I suspect the reason the word (forgive me) came to me is actually Alan Moore's spoken word performance of Unearthing, specifically the passage "It's the Met, the Obscene Publications Squad. No warning sirens and no backyard shelter for the R. Crumb cum-shots or the S. Clay Wilson severed pirate-dicks to huddle in until everything's over. There's no ack-ack shooting back: during all this his father dies, a golf-course stroke, just short of turning sixty-five. The pulmonary guns fire everything they've got into a popping strobe-lit heaven, emptying the chambers."

The bulk of the description of "The Villain" in both this entry and the previous one is shameless Moore pastiche on my part, and between the stark white splatters of the fireworks and that passage, it just sort of appeared on my screen, daring me to delete it.

December 10, 2014 @ 8:58 pm

What's funny is that this isn't actually that out of line with Moore's thinking, as we'll discuss much later in this chapter.

December 10, 2014 @ 10:16 pm

I wouldn't be surprised if the film's lawyers did some negative checking, found out Violet Carson was a real person and insisted on changing it.

December 10, 2014 @ 11:18 pm

A real dead person by the time the film was made. My suspicion is that they figured some popcorn munching dumb-fuck in a multiplex might get confused about a red rose being called violet. Which is probably just the sort of thing Alan Moore hates about Hollywood.

December 10, 2014 @ 11:19 pm

colour me…intrigued.

December 10, 2014 @ 11:24 pm

Loved the imagery and the phrase now has even more resonance if intoned in an imagined approximation of Phil Sandifer impersonating Moore's Northampton drawl.

December 11, 2014 @ 1:59 am

Jumping ahead a bit, I guess, but I'm really, really not sure V in it's entirety can be read as a straightforward rejection of violence. Evey may chose to reject violence at the close, but I have a hard time projecting her successful revolution without old V having both 'cleared the decks', as it were, and also by the fear his actions will have instilled in what's left of the regime in terms of the length the revolution will go. My take on the book was that it seemed to be saying that there was a time for violence, and a time to end the violence. It's been a few years since I read it, mind, but I did read it a few times. It's probably my favorite Moore work, maybe my favorite comic ever.

December 11, 2014 @ 3:14 am

I took it that way also. The reason V is, proclamations about villainy notwithstanding, the real hero of the piece is that he is aware that his violence is necessary, but he is equally aware of its danger, and that it must come to an end and be transcended.

December 11, 2014 @ 4:32 am

This reminds me a little of something I read (either in the Axel Pressbutton section of the War or elsewhere) about the Moores, Steve and Alan, having some kind of crazy idea of a shared V For Vendetta/Marvelman/Pressbutton universe.

December 11, 2014 @ 9:35 am

This is contrary to Moore's view, certainly. But also a matter for Book Three, so something I've not poked at too intensely. (I've reread the first 2/3 of V four or five times in the last three months. I've read the ending once in that time.)

December 11, 2014 @ 9:45 am

Ice has the gist of it. There's a future history timeline from the Moores reprinted in Kimota that sheds some light on this.

December 11, 2014 @ 12:30 pm

Well I'm looking forward to seeing you cover that almost as much as you getting to The Invisibles and The Filth.

December 11, 2014 @ 12:39 pm

I hope nobody minds if I go on a barely related tangent here. I'm currently reading The Invisibles back issues (usually I read trades or digital like Comixology) and Morrison's letters pages are a lot of fun.

One thing I find amusing, with relation to The War, is multiple instances where he says he's been reading Alan Moore's then contemporary WildC.A.Ts stuff.

December 11, 2014 @ 9:45 pm

Oh yes those letters pages. The wankathon! The detailed descriptions of Morrison's drug experiences/ufo abduction, the slow realisation from Morrison that, in King Mob, he had created a monster avatar/voodoo dolly, leading to the decision that after torturing KM/himself nearly to death it was going to be sex n drugs n rock n roll all the way down from then on. Heady days.

December 11, 2014 @ 9:55 pm

I first read The Invisibles in trade, where it pretends to be a coherent Vertigo series in the same way that, say, Sandman or Preacher is.

Such a lie, I've discovered. The series only works in single issues. It's a hot mess in trade, but those single issues, if you pay attention to the dating and the delays and imagine the book as the "comics as pop" extravaganza that it was, it's like Morrison's Berlin Trilogy.

Which I think makes The Filth his Scary Monsters. I'll take that, actually. Huh. Can you do a solid Morrison as Bowie analogy? (I smell a future Waffling.)

December 12, 2014 @ 8:35 am

I'd say Zenith is his Hunky Dory, Animal Man his Ziggy Stardust, Doom Patrol his Aladdin Sane, Arkham Asylum is Diamond Dogs, the JLA run his Let's Dance, Captain Clyde is probably his Laughing Gnome and Final Crisis is 1:outside/Tin Machine. Does this make Mutiversity The Next Day?

December 13, 2014 @ 6:47 pm

I'm glad you made the point about Moore's use of the particular advantages of the medium (text vs. images), because that's one of the reasons V for Vendetta is one of my favorite books.

December 18, 2014 @ 12:44 pm

anyone know if Moore was influenced by the short-lived new future '1990' featuring Edward Woodward?