Dawn Transformed the Sky into an Abattoir (The Last War in Albion Part 20: Moores’ Doctor Who Comics)

This is the third of seven parts of Chapter Four of The Last War in Albion, covering Alan Moore’s work onDoctor Who and Star Wars from 1980-81. An ebook omnibus of all seven parts, sans images, is available in ebook form from Amazon, Amazon UK, and Smashwords for $2.99. The ebook contains a coupon code you can use to get my recent book A Golden Thread: An Unofficial Critical History of Wonder Woman for $3 off on Smashwords (the code’s at the end of the introduction). It’s a deal so good you make a penny off of it. If you enjoy the project, please consider buying a copy of the omnibus to help support it.

“It would be equally irresponsible of me to instruct up-and-coming writers on how to write sickly extravagant captions like ‘Dawn transformed the sky into an abattoir’ or whatever.” – Alan Moore, Writing For Comics

PREVIOUSLY IN THE LAST WAR IN ALBION: Steve Moore, Alan Moore’s closest friend and confidant over the course of the War, came to work on Marvel UK’s newly launched Doctor Who Weekly in 1979, where he created the character of Abslom Daak, a close cousin of the Axel Pressbutton character he co-created with Alan Moore and wrote for Warrior. In one issue of Warrior, Moore interviewed his own “Pedro Henry” pseudonym on how to write comics…

On one level this is the same sort of tightly structural approach that characterizes Alan Moore’s work. But on another, there’s a fundamentally different sort of focus. As Steve Moore puts it, “if Dez asks for six pages, you give him six… the same as some editors will ask you for a set number of frames… and if they say forty frames, they don’t mean thirty-nine or forty-one. If you turn up saying ‘Sorry, boss, I couldn’t fit it in so I’ve used four extra frames’ then that, quite simply, is bad writing.” This highlights the degree to which Steve Moore writes his comics as a professional concern, within the material realities of publishing. That’s certainly not to say that Alan Moore doesn’t, but there’s a clear difference between the sort of ruthless targeting of what the editor wants and the storytelling Alan Moore engages in.

This perspective on Steve Moore’s work helps explain the odd tone of Laser Eraser and Pressbutton. Moore was tasked with a specific set of editorial concerns; revamp the old Abslom Daak strips into something for Warrior, using the comedy character of Axel Pressbutton. That the resulting script is a bit disjointed in many ways speaks to just how good Steve Moore was at giving editors what they want, no matter how strange. But it contrasts sharply with Alan Moore, who took his Marvelman revamp and his mandate to make a Night Raven clone and ran in unexpected directions with them that ended up far from the original concepts.

|

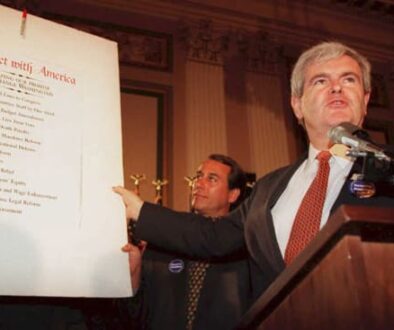

| Figure 151: Unsurprisingly, Selene made an appearance in Steve Moore’s Doctor Who comics (Steve Moore and Dave Gibbons, Doctor Who Monthly #50, 1981) |

This sort of diligence also explains why when Mills and Wagner departed the lead strip after Doctor Who Weekly #34, during the pause in the midst of Star Tigers, Steve Moore was promptly promoted to replace them. Steve Moore’s take on the Doctor Who comics was on the whole lighter than Mills and Wagner’s. Under Mills and Wagner the Doctor Who Weekly comic felt like a strange hybrid of Doctor Who and 2000 A.D. – which was, after all, the point of the exercise. Steve Moore’s stories, on the other hand, have an altogether more poetic lilt to them. His first strip, Doctor Who and the Time Witch, features Doctor Who locked in a mental battle with a quasi-sorceress, and culminates in a scene in which the sorceress’s brutish henchman is split into two by the Doctor and the sorceress giving it conflicting commands (she wants it to kill Doctor Who, he wants it to make a cup of tea), resulting in two identical henchmen pounding on each other. Another story featured Doctor Who meeting what appear to be the literal Greek gods (including, inevitably, Selene), and ends up rescuing Prometheus from a prison on Olympus so he can seed the galaxy with life.

|

| Figure 152: Steve Moore’s acclaimed 1989 study of the I Ching. |

It would be a mistake, however, to suggest that Steve Moore wrote only “funny” stories for Doctor Who Weekly (and, subsequently, Doctor Who Monthly). His second story, Dragon’s Claw, was a properly sprawling epic that mashed up the Sontarans, a particularly duff Doctor Who monster, with the kung fu movies that fascinated Moore, who is a noted I Ching scholar in addition to his work in comics and for the Fortean Times. This is particularly welcome, as on television Doctor Who never really managed to engage kung fu movies in its fifty years of genre pastiches, and when it has looked to China it has been in an infamously sinophobic way. Similarly serious is Moore’s final story for Doctor Who Monthly, “Spider-God,” an stinging eight-pager in which Doctor Who watches in horror as human surveyors butcher a colony of aliens purely because they fail to understand the nature of the alien society and lifecycle.

The promotion of Steve Moore, meanwhile, left a vacancy on the backup feature. Steve Moore informed Alan Moore, who he knew was looking to break into script-writing, of the opportunity, and passed his trial script on to editor Paul Neary. That script was entitled “Black Legacy,” and the first two-page installment appeared in Doctor Who Weekly #35, marking Alan Moore’s first job as a writer instead of as a writer/artist. Black Legacy is a fairly straightforward horror story – a team of Cybermen arrive on the barren planet of Goth, seeking the terrifying weapons created by the long-dead Deathsmiths of Goth. Over the course of four two-page installments they are steadily picked off by an unseen force, the Deathsmiths’ “Apocalypse Device,” which turns out to be a sentient weapon that seeks to be used. It turns out that the Deathsmiths in fact destroyed their own spaceships to trap the Apocalypse Device on their planet, and that the Apocalypse Device has been waiting for someone to come to Goth so it could steal their spaceship and finally unleash itself on the universe. In desperation the last surviving Cyberman destroys its ship, trapping the Apocalypse Device, only to have, in the epilogue, the Sontarans arrive seeking the weapons. The story ends with the Device musing that “this time it will escape to spread its blight across the heavens, free to do the job it was created for. It will not wait forever. That is the problem with ultimate weapons…”

|

| Figure 153: Under David Lloyd’s pen, the Cybermen became lithe and sleek creatures in contrast to the decaying horror of the Apocalypse Device (Alan Moore and David Lloyd, Doctor Who Weekly #35, 1980) |

On art duties for the story was David Lloyd, who had served as an occasional artist on Steve Moore’s backup strips, and who Alan Moore was familiar with due to their mutual contributions to the fanzine Shadow. This would prove to be a fruitful artistic collaboration not long after in Moore’s career, and even in 1980 Moore regarded Lloyd as an underrated artist with “a really powerful sense of storytelling and a starkness in his contrasts of black and white” who “had an experimental bent that was complementary to mine.” This is a fair assessment; Lloyd brings a moody line to the strip, casting Goth in deep shadows that befit the name. He draws the Cybermen with a lithe precision, taking them away from the clanking robots they had steadily become on the television series and helping to sell the script’s concept of emotionless machine men who nevertheless are overtaken by fear and paranoia.

For Moore, at least, the appeal of the gig was in part the constraints. Having squandered the first year of his attempt at becoming a professional comics creator on a story to be called Sun Dodgers that was to be a massive epic “that made Lord of the Rings look like a five-minute read” and, in that time, completing roughly half a page of it, Moore found the discipline required in two-pagers refreshing, saying that “you’ve got to kind of establish everything and have each little two-page section come to its own dramatic conclusion. It was trickier than it looked but it was a great way of learning how to write comics.” This view that short-form comics provide a useful sense of self-discipline is an oft-repeated mantra of Moore’s – in another interview, he speaks about how “if there’s some way that you could do an apprenticeship that involves short stories that is probably the best way in. It teaches you so much as a writer. In a short story you have to develop all of the characters, you have to develop the situation and bring it to an interesting conclusion, all in three or four pages. So you have to do all of the things that you will have to do in a bigger work but in a much more constrained space, which teaches you an awful lot that you can then expand should you get the opportunity to turn it into a bigger and more ambitious work.”

|

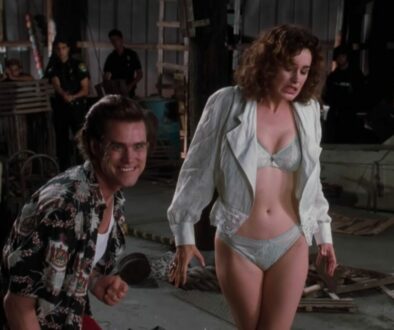

| Figure 154: The iconic scene involving the Autons comes from the 1970 serial Spearhead From Space, in which plastic shop mannequins come alive to slaughter people. |

Moore followed Black Legacy with Business As Usual, another four-parter comprised of two-page chapters. This one featured the Autons, villains made of living plastic created by Robert Holmes for a pair of stories featuring Jon Pertwee’s Doctor Who in the early 1970s. Holmes created the monsters as a comment on the increasing role of plastic as a material. In Holmes’s original stories, plastic was a metaphor for the fake and artificial – the first of them, Spearhead From Space, literalized this by having the Autons replace people with plastic duplicates. Its iconic scene of mannequins smashing their way out of high street shops to slaughter people on the street proved to be one of Doctor Who’s most enduring images, recycled by Russell T Davies in his 2005 revival of the show. The second, Terror of the Autons, broadened the reach, having not just plastic people, but various consumer products turn lethal: plastic chairs, plastic daffodils, children’s dolls, et cetera, contrasting these with a joyfully gaudy celebration of the newfound possibilities of colour television in what is arguably one of the first iconic documents of the glam rock era (itself an era concerned with questions of artifice and superficiality). But even Spearhead From Space played with this broad conceptual space, setting major scenes at a plastics factory, thus tying the themes of artificiality to industrialization.

Coming to the same themes in 1980, Moore took an appropriately updated approach. Instead of concerning himself with the by then dated issue of the rise of plastic as a consumer product, Moore focused on the Autons’ role as monsters made out of industrial practices. Business as Usual is ultimately a story about corporate intrigue, telling the story of Max Fischer, an industrial spy sent by a company called Interchem to investigate the rapidly growing Galaxy Chemicals. Its central conceit is that the alien invasion it tells about is portrayed as indistinguishable from the normal operations of a large company – business as usual, as it were. The story is a wry joke, with the Autons staging a hostile takeover in both the real-world and sci-fi senses of the phrase.

Conceptually, at least, it’s the best Doctor Who story of 1980. It’s in the execution that it falters. Moore is at times a bit too proud of his own cleverness (a problem that will dog him for his entire career), pushing his observations a touch too far in places. Little justifies the opening line of the third installment, which proclaims that Fischer “had always thought a killing was something one made on the stock market… until he discovered Autons!” And the cleverness largely fades in later installments, as the inventive premise gives way to a fairly drab extended action sequence as Fischer tries and nearly succeeds in escaping from the Autons’ wrath.

But whatever might be said about the later chapters, the first chapter is sheer genius. Moore employs one of his usual tricks of having narration that contrasts significantly with what’s being depicted in the panel, and using that contrast to reveal new sorts of information. So while the narration calmly explains how perfectly ordinary the events of the story are (in the first page Moore proclaims that “there was no-one to notice,” “there was no-one to be surprised,” “no-one raised an eyebrow,” “and it was quite normal”), while the events themselves, to a reasonably sci-fi attuned reader, are clearly the early stages of an alien invasion. This sort of contrast is further highlighted by the art of David Lloyd, who is adept at using small details to make seemingly ordinary images incongruous. So, for instance, as the Auton-controlled Winston Blunt approaches the receptionist of Interchem his eyes are drawn as wide-open, his head tilted at an angle (which matches the angle at which the entire panel below it is drawn), and his mouth is closed, giving a clear sense that something is wrong. Likewise, when Blunt appoints his successor at Galaxy Plastics, the new manager’s face is portrayed with no shadows on it whatsoever, and he stands in a rigid position such that he looks slightly wrong. Later drawings of the same character give him a face that is not dissimilar to the way that Lloyd would later draw the anarchist terrorist V in V for Vendetta.

|

| Figure 156: The wide variety of plastic-faced killers that David Lloyd can draw (L: Alan Moore and David Lloyd, Warrior #3, 1982. R: Alan Moore and David Lloyd, Doctor Who Weekly #42, 1980) |

Moore’s prose also displays techniques that will recur throughout his career. His tendency towards a poetic, rhythmic narration is often commented on, and is perfectly visible as early as Black Legacy. Consider this passage (with stressed syllables in capital letters): “but conCEALED withIN the SHADows OF the WITHered VEGeTATion, It WATches THEM. It WATCHes THEM, these GLITTerING macHINE men. as THEY erECT their FLIMsy SHELters.” It is not perfectly metered by any measure, but there’s a clear cadence to it. It’s driven mainly by iambs, save for an occasional trailing unstressed syllable at the ends of phrases (a common feature in poetry as well). Similarly, Moore’s use of repetition creates a sense of rhythm, as in passages like “Cyberleader Maxel is many things… a brutal tyrant, an enslaver of words, a callous mass murderer,” which uses a well-groomed three item list for rhetorical effect. This is the technique that Douglas Wolk has identified in Moore’s work in general, noting that “whenever he or one of his characters has something meaningful to say, the language Moore uses shifts into an iambic gallop.”

What’s immediately interesting about Moore’s early Doctor Who work is that his second story is no less metered in its narrative, but that it has an entirely different tone. Where Black Legacy sticks mostly to iambic tone, Business as Usual goes for dactyls and trochees, as with the line, “NO one RAISED an EYEbrow when BLUNT inVESTed his CAPital in FOUNDing his OWN PLASTics COMPany. IT was JUST SOUND BUSiness.” [continued]

November 28, 2013 @ 12:23 am

Oh my gosh! The Steve Moore of Axel Pressbutton fame is the same Steve Moore who wrote The Trigrams of Han? That never even occurred to me. I love that book.

Who says this blog isn't educational?

November 28, 2013 @ 12:28 am

Figure 156 is a thing of beauty, the comparison isn't quite as clear with my reprint in Marvel US's Doctor Who #15. Quick question: Is the story titled Business as Usual, or Business Unusual, or did it use different titles on different issues? (You use both above; my reprint has it as Business as Usual.)

I've heard some places that Marvel's reprinting of these stories in the US Doctor Who title was at least one of the bones of contention that led to Moore's unwillingness to work for Marvel, along with the more common stories that he was annoyed by the whole Marvelman name fiasco, and the use of Mad Jim Jaspers in X-Men #200. The Jim Jaspers story always seemed fishy to me, given that the character actually predated Moore's run on Captain Britain.

November 28, 2013 @ 2:35 am

I think I would stress WITHin and MAchine. But a felt iambic beat can sustain some amount of inversion.

November 28, 2013 @ 7:19 am

I was going to say that "Deathsmiths of Goth" sounds like a band I would avoid at all costs. Then I checked if anyone had said that before, since it seemed likely, and it turns out Phil has…

Just out of interest, when Moore came up with "Deathsmiths of Goth", would he have been aware of a subculture that I think was about a year old, or was it a coincidence?

November 28, 2013 @ 7:40 am

He lived in Northampton and was social with David J, so yes, he surely knew about Bauhaus. Did a piece on them for Sounds, actually, though I don't know the date on that.

November 28, 2013 @ 12:29 pm

The comic strip was only ever called Business as Usual. Business Unusual was the title of a Doctor Who tie-in novel featuring the Autons, riffing on Moore's title.

November 28, 2013 @ 12:45 pm

"Who says this blog isn't educational?"

No-one, ever! Personally, I've learnt quite a lot about writing and scriptwriting since the early Hartnell entries.

November 28, 2013 @ 5:54 pm

Yes – and I got scrambled writing. Will fix in just a second.