Gods and Monsters

Happy Hallowe’en.

I was watching The Bride of Frankenstein yesterday; appreciating the fact that James Whale invented the self-analysing comic horror film decades before Wes Craven thought it would be tremendously cute to have characters in a slasher film talk about the narrative rules of slasher films.

At one point, the insane, camp, gin-swigging Dr Pretorius (played by the ridiculously watchable Ernest Thesiger) shows Frankenstein (Colin Clive) his collection of creations: tiny people that Pretorius grew from cultures and… well, it’s pretty much indescribable. Watch it for yourself. If you’ve never seen it, you need to.

It isn’t explicitly said, but clearly both Pretorius and Frankenstein anticipate (the former with relish and the latter with fear) the breeding of a new race. Pretorius, for all his campness and his disdain for every human female he meets, seems interested in the breeding potential of these creations of science.

Meanwhile, Frankenstein’s monster turns out to have survived the first film and, having learned to talk, expresses his demand for a “friend”… by which he is taken to mean a woman with whom he can mate, though he doesn’t express this desire himself. What the children of Boris Karloff and Elsa Lanchester would have looked like is odd enough to contemplate by itself, without imagining babies with cuboid heads and electrified, badger-striped hairdos.

It got me thinking about the origins of the novel Frankenstein. I don’t mean all that stuff that’s supposed to have gone down at the Villa Diodati, which is depicted at the opening of Bride of Frankenstein as an arch costume drama, rather than the hazy blur of bullshitting and indolence and copping off that it probably was. I mean the work and influence of Luigi Galvani, who suggested in 1791 that electricity was an innate property of animal life, and that it might even be the “vital force”… supposedly after noticing the legs of a dead frog kicking when he touched the nerves with his scapel during a lightning storm. (I’m told he was searching for the testicles, having formed the theory that frogs kept them in their legs.) Galvani’s conclusions about animal electricity were flawed and were superceded by Volta, but ‘galvanism’ caught on as an idea. And as morbid, gothic entertainment. Galvani’s nephew Giovanni Aldini became something of a hit, giving demonstrations of how dead bodies could be made to react to electrical charges.

In one famous incident in 1803, Aldini had the corpse of a just-hanged murderer, George Foster, brought from Newgate to the Royal College of Surgeons, where he electocuted the body, causing its jaw to twitch and one of its eyes to open. When Aldini probed its rectum, the body is said to have arched and kicked and raised its fist as though in fury. Well, you would, wouldn’t you? This was one of many such experiments carried out by many scientists at the time. There was another guy who claimed to have briefly reanimated some decapitated kittens. Awwwww.

According to Mary (writing well afterwards) these experiments were one topic of discussion amongst the bright young things – Byron, Shelley, Mary herself, et al – at the Villa Diodati, alongside the experiments of Dr Erasmus Darwin. Erasmus Darwin – the grandfather of Charles – was supposed to have bestowed life on pasta, much to the fascination of many people. Mary claimed that this story, combined with the experiments in galvanism, inspired her to think that a creature might be constructed from parts and then be brought to life.

Erasmus Darwin – who had known Mary’s father, the radical philosopher William Godwin – was, interestingly enough, a proto-evolutionary thinker. In Zoonomia and some of his poems, Erasmus put forward (sometimes obliquely) notions of life developing and changing. His last poem traces life from primordial soup (presumably minestrone with sentient noodles in it) to modern society. It was a hit with Romantics like Wordsworth.

The later Darwin would agonise over publishing his findings, knowing that he would be subject to fierce attacks by those who saw natural selection as dethroning God. Which is what Mary’s story is supposed by many to be about: a scientist who challenges God. The idea that Frankenstein has ‘played God’ has far more life outside of the novel than inside. It isn’t a central concern of the book. By contrast, the first theatrical adaptation was called Presumption! or The Fate of Frankenstein, and in James Whale’s films people harp on at length about how Frankenstein has meddled in things that man should leave to God. Of course, in Whale’s movies, this is surface patter, lying on top of the deeper concerns.

Whale himself was both irreligious and openly gay.

Many film critics have suggested that the films, especially Bride, can be subject to a gay reading. They point to the way the camp Pretorius separates Frankenstein from his future wife (his bride, you might say) and propositions him, suggesting that they collaborate in creating new life from seed, as though Pretorius is attempting some kind of gay biological procreation. Meanwhile, the Monster (who is a despised and hunted outsider) uses one word for all prospective relationships, be they with men or women: “friend”. His friendship with a blind pauper is interpreted as a potential marriage, interrupted by ignorant and intolerant yokels. Ultimately, he is incompatible with the “bride” that Frankenstein and Pretorius create for him.

The other way that this film is often read is as a Christian allegory. The Monster is put into Christlike poses several times, especially when captured, tied to a pole and raised in the air, his hands tied above his head. Crosses abound (though most of these are in the film because several scenes take place in a graveyard). And so on.

I can’t pretend to be sufficiently familiar with the critical literature to evaluate these claims. Apparently, a lot of people who knew James Whale consider them bullshit – but then they don’t need to have been intentional in order to be present in the texts.

There’s an interesting (if flowery) article about this stuff here.

Anyway, it’s impossible to deny that a story about a creator who makes a man, gives him free will, turns him out into the world and then comes into conflict with him has to be, in some way, a reiteration of ‘Genesis’.

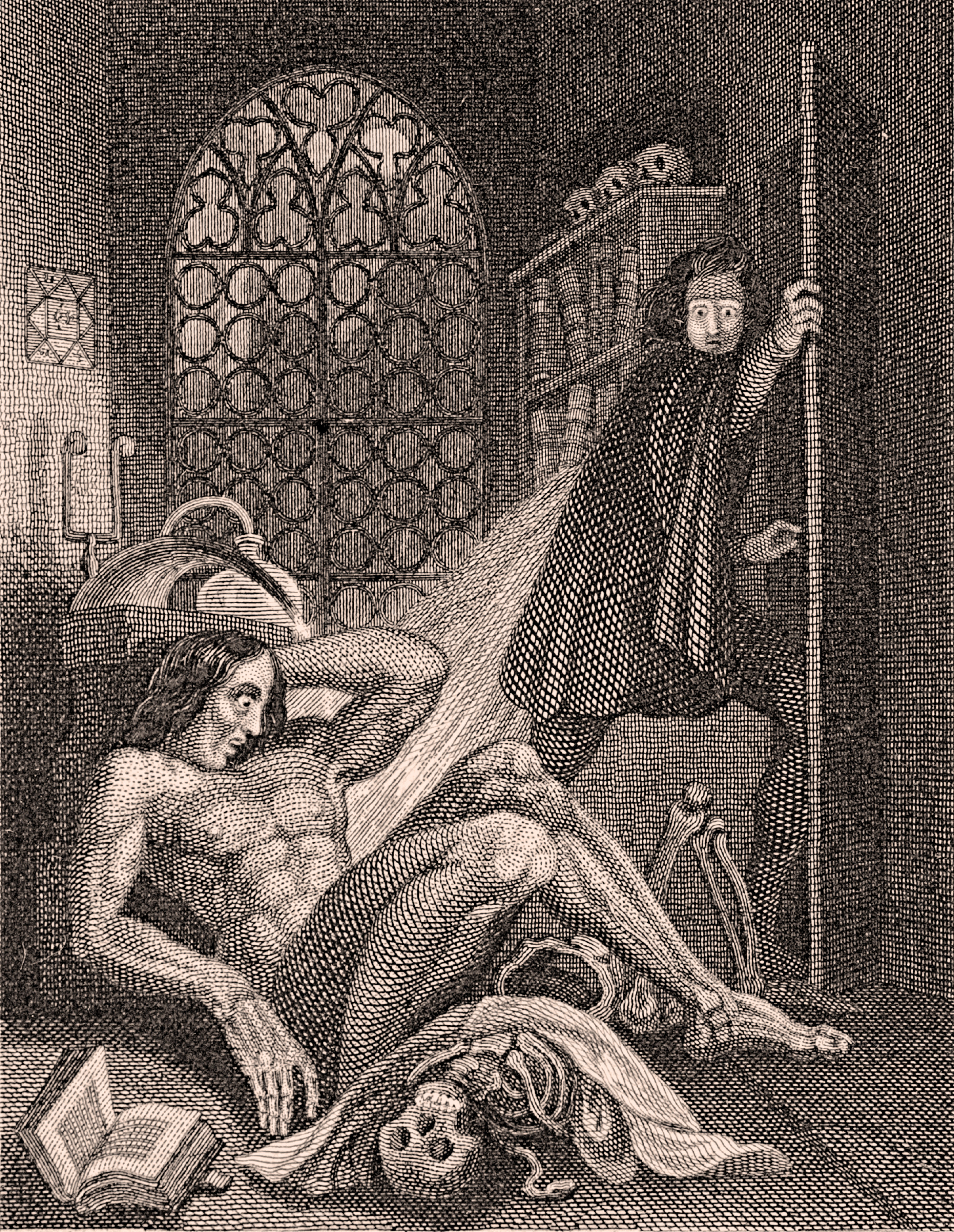

In light of this, it’s interesting to look at the first ever depiction of the Monster, an engraving created for the 1831 publication by the truly great and shamefully undervalued artist Theodor von Holst.

There’s more than a slight resemblance. Adam, of course, doesn’t have to take in the sight of his creator’s eyes wide with horror as they look upon him… not just yet anyways.

That’s why its amusing to think of the Character Options toys that so many of us Who fans collect (no doubt made with oil that has to be controlled through invasions of which many of us disapprove). We’re like Dr Pretorius, playing with his little people in jars. Gods playing with our monsters. Just make sure you keep the lid on the jar with Cpt. Harkness in it… unless you want your little people to breed.

Anyway, I’m tired of all this brainstorming. Hallowe’en is over.

Good night. If you can.

February 24, 2025 @ 2:10 pm

One point of contention. Though I wasn’t alive at the time of the original broadcast of War o/t Worlds, I find the argument that the broadcast was so succesfull in deceiving it’s listeners ‘because the American people were skittishly aware that they were on the brink of entering World War II’ not very convincing, for in 1938, there was no War for them to enter, let alone a World War. International tensions, I’d readily agree to, but England and France only declared War on Germany after Germany invaded Poland, and it wasn’t until Germany defeated France in June 1940 that Germany’s reach would extent to the Atlantic Ocean. The Tripartite Act, adding Japan to the already existent Axis of Germany and Italy was only signed in September 1940, turning the already looming conflict with Japan into a potentially larger conflict, even though Germany was by no means bound by the Tripartite Act to aid Japan in the War they instigated by attacking Pearl Harbor. Maybe the mood in the country was different, that could very well be, but there simply was no existing World War to enter in 1938, unless one wishes to convey the impression that people considered a future conflict to be unescapeable.

February 24, 2025 @ 5:56 pm

In fact, the opening monologue to the radio play mentions that “the war scare was over”.