Last War in Albion Book Three, Chapter 11: A Small Killing

“Within a fortnight it can all fall down, the luminous Wurlitzer palace of our youth: no luck, no school, no happy home. The job down at the skinning yards… the tide comes crashing in, and sweeps us all away.” – Alan Moore, The Birth Caul

Although the slow motion disaster of Big Numbers, along with his less ruinous but still time-consuming efforts on From Hell and Lost Girls, occupied much of Moore’s time in the wake of Watchmen, these sorts of projects—self-published or put out in friends’ self-published anthologies—were not what he’d initially imagined his post-DC career to be. As he put it, “my intentions at that time were that I would work for book publishers. I was getting an awful lot of offers from book publishers asking me to do graphic novels for them, which seemed like a good option to me because I’d own my copyright, I’d be dealing on more equitable, grown-up terms.” In practice this never materialized, in part because the graphic novel boom that was leading these book publishers to take interest in the medium was quickly being squandered by the actions of the very publishers Moore was leaving. In practice, Moore would only publish one work with such a publisher, a 96 page graphic novel called A Small Killing that he did for Victor Gollancz’s short-lived VG Graphics imprint.

Victor Gollancz was notable, at least in the late 1980s, as one of the UK’s most prominent family-owned businesses, existing since the 1920s and publishing authors such as George Orwell, Daphne du Maurier, Kingsley Amis, and John le Carré. In the 1960s the publisher became a notable science fiction publisher, developing an eye-catching yellow trade dress that stood out and helped establish the publisher as a brand unto itself. In 1990, however, in the midst of Moore’s work on A Small Killing, Gollancz was sold to the US publishing giant Houghton Mifflin, which in turn sold it on in 1992, with a third and final sale coming in 1998. Combined with the petering out of the graphic novel boom, A Small Killing became a niche title—it got an American edition from Dark Horse in 1993, and then came back into print in 2003 from Avatar as part of their authorized ransacking of Moore’s back catalog. Moore would eventually identify it as “the most underappreciated work that I’ve done.”

Working with Moore was Oscar Zarate, an Argentinian artist who grew up as a devoted fan of Alex Raymond and Hugo Pratt and worked as an assistant in the Argentinian industry before migrating to advertising and, in 1971, Europe, this latter move to escape the right-wing military government of Argentina. There he sought work and ended up working for the Writers and Readers Publishing Cooperative, where he worked with writer Richard Appignanesi on Lenin for Beginners and Freud for Beginners, part of the collective’s iconic For Beginners series, which used comics as a medium to explain the thought of prominent philosophers and scientists. He went on to illustrating comics adaptations of Shakespeare and Marlowe before, in 1987, connecting with comedian Alexei Sayle for a graphic novel called Geoffrey the Tube Train and the Fat Comedian.

Sayle was one of the vanguards of the 1980s alternative comedy movement that hit its popular zenith with The Young Ones, where he played a rotating set of auxiliary characters, often relatives of the gang’s landlord within the Balowski family. An overtly leftist and openly socialist comedian, in 1984 he penned Train to Hell, a comedic mystery that Moore read on the plane for his first trip to the US not long after it came out. This book also resonated with Zarate, who contacted Sayle to propose a collaboration on the grounds that “what he was saying in his words had to do with what I was saying in pictures. The starting point was something on London. We’d both moved here 16 years ago, Alexei from Liverpool.”

The plot, s

uch as it was, concerned Alexei Sayle’s struggles after being slapped with an injunction by an unscrupulous manager that prevented him from doing comedy. This is, it’s clear, a fictionalized and comedic version of Sayle—he gets his arm bitten off by a fish on the second page, and makes tongue in cheek observations like “My motto in show business had always been ‘never be nice to anybody on the way up because I’m not coming down again.’” Without comedy, Sayle settles on doing a children’s book, Geoffrey the Tube Train, which eventually begins to blur with his life as he gets dragged into a series of bizarre Tube murders, eventually concluding that Geoffrey and Driver Bob, his divorced conductor, are murdering “complete wankers,” leading Sayle to team up with them to continue the work.

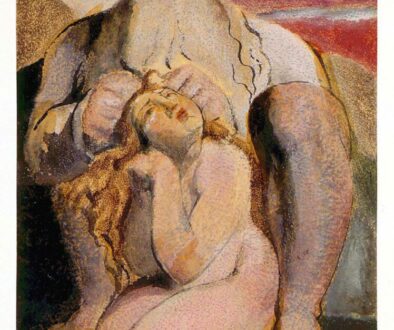

The resulting book was a broad satire, freely mixing Sayle’s over the top descriptions of his every day life (an extended section explains how because “the majority of architects are dedicated anarchists” the tower block in which he lived, Bluebird Farm was designed “in such a way that violent social upheaval was a certainty. Miles of piss-stained corridors, tunnels and gantries. Over the years Bluebird Farm had come to resemble a battlefield—specifically the Ypres Salient in the summer of 1916.”) with pastiches of Wilbert Awdry’s politely fascist Railway Series, adapted to television as Thomas the Tank Engine around the same time as Sayle was doing The Young Ones and more outright esoteric sections—there’s a lengthy riff on a prehistoric enclave of the UK full of dinosaurs. All of this is accompanied by elaborate panoramas by Zarate, whose style veered merrily from a S. Clay Wilson-inflected underground to photorealism to Murnau-esque expressionist horror to a more orthodox sort of cartooning, always managing to harmonize these influences into a luminous, painterly style. In spite of the absurdity, Zarate argued that the comic “tackles serious issues. It’s not fatalistic, it’s pointing out what is going on. It’s more like a mental state than any specific topical satire.”

Sayle became a friend of Moore’s—he’s quoted in Jerusalem describing Moore’s stand-in character Alma Warren’s oversized spliffs as “nine inch Gauloise dick-compensators,” and contributed, with Zarate, a page to AARGH, which had the effect of introducing Zarate to Moore. As with Sayle, Zarate pitched Moore on working together, which Moore, who quickly accepted, having enjoyed Geoffrey the Tube Train and the Fat Comedian and, more to the point, being intrigued by Zarate’s pitch, which, as Moore recounts it, was simply “I want to do a book with you. I’ve got an idea. There is a man walking down the street and following him is a little boy. That’s my idea.” Moore was intrigued, and began thinking about the image. He was reminded of an old nightmare he’d had “when I was a teenager or in my early 20s of meeting myself as a child and realizing that the ten-year old was horrified by what I’d turned into, what I’d ended up as. I kind of thought that that would be an interesting thing, if this child that is following this man in Oscar’s image was him or some ghost or phantasm of him as a child, and that you could make this story say something about the gap that exists between our childhood dreams or ambitions or ideals and some of the people we end up being.”

The broad strokes of the comic extended rapidly from that. As Moore recounts it, “We were talking about the culture of the 1980s of Margaret Thatcher’s Britain, we were talking about the way that that culture had changed, and we were talking about the moral changes that had been made by people immersed in that culture.” This, obviously, was similar territory to what he was already exploring with Big Numbers, but where that was necessarily a book about huge ideas, Zarate’s central image and Moore’s idea of someone being haunted by his own childhood self’s disgust with how his life turned out necessitated a different approach, one that was literalized in the title. Where Big Numbers was, well, big, A Small Killing was a more intimate, personal take on its themes. Ultimately Moore and Zarate settled on a character named Timothy Hole, an advertising executive working in New York who returns home to the UK, pursued by a mysterious child he grows to recognize as himself.

Moore and Zarate’s collaboration was an unusual one for Moore, with Zarate proving a more active partner than most of Moore’s artistic collaborators. Moore’s scripts are, of course, famously hyper-detailed things. As Moore, tongue only slightly in cheek, notes, “Everyone thinks I’m such an intellectual, so I do these scripts that are about that thick, and no-one’s going to argue with that much script are they? They’re going to think, ‘Gosh, this guy knows what he’s doing.’ Despite the fact that I make a big show of being very fair to artists and accepting their ideas, what I really do, if I’m being totally honest, is completely cow them and frighten them by doing these huge scripts, so that they’ll do exactly what I want. Y’know, I’m a bit of a Nazi when it comes down to it.” And his scripts did, in practice, have that effect—Sienkiewicz has noted that “with Alan it felt like, he’d say ‘look, here’s my ideas, go ahead,’ and I felt like I couldn’t really do that. Even though he may have said it was okay, I think it would have upset the flow or the rhythm. It’s like locking somebody into a closet and saying ‘if you want to play football, go right ahead.’ I’m not saying he locked me into anything, but I felt so much respect for what he was trying to do that, for me a big leap was to give a character a beard.” But this process simply failed to work with Zarate, who, “being a feisty Argentinean lad-or as he puts it, ‘I am a poor Gaucho boy who misses ze pampas.’ I expected him to have a certain amount of godlike reverence for me, basically. And I feel disappointed if that isn’t observed. But Oscar, he was brutal with me, he treated me like I was just some sort of ordinary human being!”

(It is necessary here to pause and briefly acknowledge an aspect of Moore’s relationship with Zarate. it is an unavoidable fact that when Moore talks about Zarate, he has a habit of adopting a comically exaggerated Argentinian accent that can only be described as “fucking racist.” There is context here that ought to be acknowledged—it is clear that the two are in fact good friends. They’ve worked together multiple times, usually on smaller work—Zarate contributed some art to Dodgem Logic, Moore did a few pieces for Zarate’s It’s Dark in London collection—and there are multiple mooted projects that the two have talked about. Zarate has never publicly commented on Moore’s impressions of him, which may well be part of a good natured and mutually appreciated running joke between two friends. This possibility does not, however, lessen the degree to which it is, as the idiom goes, not a great look.)

Zarate’s engagement with the comic was substantive. Moore recounts one time in which Zarate objected to a page, saying, “‘No, this is a seduction; you ‘ave seduced the reader. I do not like this, that you have seduced them.’ And I’d think, what’s he talking about? But generally he’d be right.” Zarate, meanwhile, explicitly takes credit for a narrative thread running through the entire graphic novel. “The narrative timing is mine,” he says. “I told Alan, ‘[Timothy] has to work back through different means of locomotion: a plane, a train, a car, a bicycle and two legs.’ I was very involved in the fact that each chapter should be presented in this way.” The resulting collaboration was significant and satisfying to both men. For Zarate’s part, he notes that “Alan is a great listener. With him, you get to a point in which you don’t know where one person’s ideas start and the other’s finish,” while Moore notes that Zarate “was getting me to change things, and eventually I was so nervous about whether I was going to please Oscar or not, I started writing in a whole different way! It was good for me, I deserved to be taken down a peg or two, else I’d just get unbearable wouldn’t I?”

As befit the concept, A Small Killing proved to be a small and intimate comic. Moore recounts that Zarate “said, for example, that he’d like me to use captions in A Small Killing, which is something that I’ve largely given up in most of my other work.” Moore’s bombastic and poetic captions had been a key part of his breakout work, giving books like Marvelman and Swamp Thing a sense of immediate heft and weight. Here, however, he offers something more personal. The narration in A Small Killing is all first person narration from Timothy Hole. Sometimes this consists of observations on the world that let Moore make larger claims about late 80s Britain and Thatcherite culture. When Timothy arrives in London, for instance, he muses about how “Nobody’s buying these offices then. Nursery architecture like those wooden bricks they used to make, columns, blocks, triangles. No nightlife. Come five o’clock it must look like after the neutron bob. Nothing but clean buildings.” But it also gives Moore the occasion to focus tightly on a couple of key images that Moore uses to structure Hole’s internal landscape: the hollowed out robins’ eggs that he collected as a child and that were broken at a party shortly before he left to fly back to England, the jar full of insects he collected and buried as a child, and the failure of his marriage.

Hole is quickly painted as an unsympathetic character. From the first panel he’s established as a neurotic, faintly unpleasant person, with the narrative joining him on an airplane, looking at a bathroom, mid thought at “…occupied. Still occupied. Bang the door, then. See who answers… no,. God, no, don’t, not after customs. Everybody things I’m perverted already, if I start knocking toilet doors, no, definitely not… customs… bastard American fucking ignorant… it was Nabokov! I mean, Nabokov! And he sys… oh, forget it. Forget it. It’s in the past now.” His monologue continues in tis vein, with casual and low grade homophobia and blandly judgmental phrases like “some old woman suffering from Boeing Bladder.” The picture only deepens as the comic goes on and Moore depicts Hole’s sexist mutterings like “When I think, how she treated me, that thing with the baby, I mean, what did she want me to say? They go on and on about women’s right to choose, then want you to choose for them. It’s…,” and deepens further when flashbacks actually depict the selfish way in which he ended the marriage, after having an affair, or his self-justifying description of it as “just something left over from when we were kids. It wasn’t real. Luckily, I was mature enough to realize that.” But there is also something faintly and clearly pathetic in Hole’s wretchedness. The breaking of the robin’s eggs is indicative, with Hole first, before they break, writing them off as “not anything, I just used to collect them when I was at school. I… they’re nothing, really,” and then, when they break, idly saying “Don’t worry, I was going to throw it out before I went on holiday anyway. It’s nothing. Really.” The overall portrait is of a bland coward—a man who sold his soul and, worse, didn’t even get a very good price.

“Our nameless, nebulous micromovement championed the band as lifestyle, as brand, anticipating Facebook and the spread of this variety of self-mythologizing into every corner of the networked life. The music was just part of the show, along with the clothes, the homemade zines, and the photo sessions: a cargo cult re-creation of an imagined life where we were headlining stadia, not local cafés, with ten million screaming fans instead of no girlfriends and no money.” – Grant Morrison, Supergods

Moore esconces this portrait in a larger structure of regression. The graphic novel is divided into four chapters, titled New York, London, Sheffield, and the Old Buildings, each introduced on a splash page of Hole traveling in one of Zarate’s prescribed vehicles with a range of dates indicating when Hole lived there. And, of course, as he moves backwards over his own life and history Hole finds himself pursued by a young boy, his own younger self, who calmly admits that, yes, he does in fact want to kill his older self for having betrayed him so.

This small, tight focus on one man’s psychological landscape and its bleed into the space around him—a sense that is heightened by Zarate’s flexible expressionism—allows Moore to paint the pressures and degradations of Thatcher’s England not in the broad and systemic ways he tried to in Big Numbers, but in terms of how one idealistic man became a cynical advertising executive who did terrible, cruel, and, worst of all, banal things to the people he loved.

In this regard, Moore is mining similar conceptual territory to what the American novelist Bret Easton Ellis was exploring in American Psycho, which also saw publication in 1991. That novel was a first person narration from Patrick Bateman, a rich banker in New York City who describes his life of vapid luxury. As with A Small Killing, all of this is painted as deeply unpleasant and unsympathetic from the start. The book’s opening scene sees a character who remarks, upon seeing a homeless person, “‘That’s the twenty-fourth one I’ve seen today. I’ve kept count;’ Then asks without looking over, “Why aren’t you wearing the worsted navy blue blazer with the gray pants?’”, and the picture only darkens from there as the arrogant and casually abusive group of bankers swear at taxi drivers, mockingly ask panhandlers if they take American Express, and generally act like a bunch of entitled pricks. But the novel hints at further depths towards the end of the chapter, when a character asserts that Bateman is “not a cynic… He’s the boy next door, aren’t you honey?” and Bateman quietly asserts to himself, “No I’m not, I’m a fucking evil psychopath.” As the book goes on, it becomes clear what Bateman means—at around a third of the way into the book Bateman describes brutally and more or less arbitrarily disfiguring a homeless person, and before long he’s narrating, at great and sickening length, a series of brutal murders, rapes, mutilations, and other general depravities.

Ellis is a mainstream literary author—asked in 2016 for his ten favorite books he gave a list populated by classic writers like Joyce, Fitzgerald, and Tolstoy along with more contemporary greats like Philip Roth and Jonathan Franzen. And yet reading American Psycho one is left with the distinct impression that its primary influence is J.G. Ballard’s The Atrocity Exhibition, with Ellis freely pilfering Ballard’s list-based approach. The book’s third chapter opens with a two thousand word unbroken paragraph in which Bateman describes his apartment, luxuriating over details like his “thirty-inch digital TV set from Toshiba; it’s a high-contrast highly defined model plus it has a four-corner video stand with a high-tech tube combination from NEC with a picture-in-picture digital effects system (plus freeze-frame); the audio includes built-in MTS and a five-watt-per-channel on-board amp. A Toshiba VCR sits in a glass case beneath the TV set; it’s a super-high-band Beta unit and has built-in editing function including a character generator with eight-page memory, a high-band record and playback, and three-week, eight-event timer.” He also finds time to describe how “On weekends or before a date I prefer to use the Greune Natural Revitalizing Shampoo, the conditioner and the Nutrient Complex. These are formulas that contain D-panthenol, a vitamin-B-complex factor; polysorbate 80, a cleansing agent for the scalp; and natural herbs. Over the weekend I plan to go to Bloomingdale’s or Bergdorf’s and on Evelyn’s advice pick up a Foltene European Supplement and Shampoo for thinning hair which contains complex carbohydrates that penetrate the hair shafts for improved strength and shine. Also the Vivagen Hair Enrichment Treatment, a new Redken product that prevents mineral deposits and prolongs the life cycle of hair. Luis Carruthers recommended the Aramis Nutriplexx system, a nutrient complex that helps increase circulation,” and details a kitchen setup where “Next to the Panasonic bread baker and the Salton Pop-Up coffee maker is the Cremina sterling silver espresso maker (which is, oddly, still warm) that I got at Hammacher Schlemmer (the thermal-insulated stainless-steel espresso cup and the saucer and spoon are sitting by the sink, stained) and the Sharp Model R-1810A Carousel II microwave oven with revolving turntable which I use when I heat up the other half of the bran muffin. Next to the Salton Sonata toaster and the Cuisinart Little Pro food processor and the Acme Supreme Juicerator and the Cordially Yours liqueur maker stands the heavy-gauge stainless-steel two-and-one-half-quart teakettle, which whistles “Tea for Two” when the water is boiling, and with it I make another small cup of the decaffeinated apple-cinnamon tea. For what seems like a long time I stare at the Black & Decker Handy Knife that lies on the counter next to the sink, plugged into the wall: it’s a slicer/peeler with several attachments, a serrated blade, a scalloped blade and a rechargeable handle.” This is recognizable as producing the same sort of alienation as the hyper-detailed catalogs of Ballard’s work, the endless brand names and intimate details of shampoo ingredients and VCR components serving not to give the reader more insight into the details but to ensure that all the description of casual wealth blurs together into a sort of hostile white noise. (The section ends, interestingly, with Bateman watching a TV talk show about a woman with multiple personalities who says that at the moment she’s “Lambchop,” a name Ellis surely got out of Truddi Chase’s When Rabbit Howls.)

As the novel takes its turn into brutal murder, Ellis maintains the dispassionate, list-based style. A description of a particularly awful murder includes the note that “Her breasts have been chopped off and they look blue and deflated, the nipples a disconcerting shade of brown. Surrounded by dried black blood, they lie, rather delicately, on a china plate I bought at the Pottery Barn on top of the Wurlitzer jukebox in the corner, though I don’t remember doing this. I have also shaved all the skin and most of the muscle off her face so that it resembles a skull with a long, flowing mane of blond hair falling from it, which is connected to a full, cold corpse; its eyes are open, the actual eyeballs hanging out of their sockets by their stalks. Most of her chest is indistinguishable from her neck, which looks like ground-up meat, her stomach resembles the eggplant and goat cheese lasagna at Il Marlibro or some other kind of dog food, the dominant colors red and white and brown. A few of her intestines are smeared across one wall and others are mashed up into balls that lie strewn across the glass-top coffee table like long blue snakes, mutant worms. The patches of skin left on her body are blue-gray, the color of tinfoil. Her vagina has discharged a brownish syrupy fluid that smells like a sick animal, as if that rat had been forced back up in there, had been digested or something.” The entire point here—as the references to the Pottery Barn and Il Marlibro make clear—is to erase the distinction between this sort of list and the earlier descriptions of tedious luxury.

The comparison to Ballard is also apt in terms of the reception to Ellis’s book, which got a helpful publicity boost when its original publisher, Simon & Schuster, abruptly terminated the book contract following a small media storma about what the book would contain, resulting in the book migrating to Alfred A. Knopf, who published it as a paperback that got widely pilloried in the press (the New York Times described it as “the journal Dorian Gray would have written had he been a high school sophomore. But that is unfair to sophomores. So pointless, so themeless, so everythingless is this novel, except in stupefying details about expensive clothing, food and bath products, that were it not the most loathsome offering of the season, it certainly would be the funniest.”) before going on to be widely recognized as a literary masterpiece and one of the major books of its era, perfectly encapsulating the awful spirit of the times.

Put another way, American Psycho is a classic of the sort of willfully puerile edgelord aesthetic embodied by Garth Ennis or Mark Millar—essentially the Summer Offensive only with fewer editorial restrictions and more literary respectability. But among the things it shares with Mark Millar is its pervasive sense of nihilism. As the book goes on, it becomes increasingly clear that Bateman’s atrocities are simply his own pathetic fantasies, that he is not some brutal serial killer awash with seedy glamor but simply an asshole imprisoned by his meaningless luxury life who imagines raping and murdering a woman and trying to cook her corpse because nothing else lends his existence anything approaching meaning, so that at the end of his fantasized murder he’s “unable to find solace in any of this, crying out, sobbing “I just want to be loved,” cursing the earth and everything I have been taught: principles, distinctions, choices, morals, compromises, knowledge, unity, prayer—all of it was wrong, without any final purpose. All it came down to was: die or adapt. I imagine my own vacant face, the disembodied voice coming from its mouth: These are terrible times. Maggots already writhe across the human sausage, the drool pouring from my lips dribbles over them, and still I can’t tell if I’m cooking any of this correctly, because I’m crying too hard and I have never really cooked anything before.” For Ellis, the yuppie lifestyle is a prison, and indeed a hell—the book starts and ends with Bateman reading a bit of signage, the first “Abandon all hope ye who enter here,” the last “this is not an exit.”

This is very much not the direction that Moore and Zarate go in with A Small Killing. In some ways this is surprising, or at least was surprising in 1991. It is easy, with hindsight, to forget that in the wake of his DC career, Moore was very much associated with this aesthetic. He’d come up being mentioned in the same breath as Frank Miller, and a casual glance at his work that noticed the “superheroes grow up” themes of Marvelman and Watchmen, the general prevalence of rape, and perhaps a few details like defying the Comics Code Authority over zombie incest rape in Swamp Thing or the whole “cripple the bitch” incident could easily leave someone with the impression that Moore was, at his heart, an edgelord. Even a deeper investigation at the time could have led to this belief. He is, after all, a writer with a deep affection for the Underground Comix scene of R. Crumb and S. Clay Wilson, and the man who wrote “Driller Penis: Yes… He Does What You Think He Does.” To assume, in 1991, that Moore and Bret Easton Ellis were fellow travelers would not have been beyond justification.

But this was the very part of Moore’s career that he was seeking most adamantly to escape. And A Small Killing, like Big Numbers’s almost petulant refusal to be about anything superhero fans would call conventionally interesting. As Zarate put it, Moore “wanted to move in some other way. After that enormous thing he did, Watchmen, he wanted to talk about other things, and it seems our encounter happened at the right time.” To this end, Moore insisted early on that the comic would have a happy ending, which suited Zarate “because I haven’t thought about how I wanted it to end. I suppose that had much to do with him, because he was coming from a very apocalyptic thing like Watchmen.” And so A Small Killing ends with the inevitable confrontation. By this point in the story Timothy has returned to where he grew up, to tiny hole in the ground where he did what he earlier in the comic described as the worst thing he’d ever done in his life, gathering up a bunch of insects in a jar and burying them alive. To his horror and astonishment, he finds a jar buried in the ground, though it’s too big, impossibly big. He pries the lid off, and a torrent of giant, bizarre insects pours out, rendered in a full splash by Zarate, who makes them look like some sort of Lovecraftian representation of absolute alienness. Timothy vomits, terrified, and at that moment his younger self appears at the top of the hole. Flummoxed and confused, Timothy asks why the child wants to kill him, and the child offers a simple, brutal reason: “You killed me first.”

And so begins a battle every bit as apocalyptic as the rain-drenched fisticuffs of Moore’s by this point decade old battle between Marvelman and Kid Marvelman—in its own way, perhaps, every bit as apocalyptic as the rapidly expanding War that Moore is still not quite aware he’s engulfed himself within. They fight, brutally, fully intent on killing each other, as Zarate pulls the perspective backwards, the hole disappearing into the middle distance, and beyond. Over this is narration: “The way to handle the Russian campaign is like this,” Hole explains, addressing one of the thematic elements that Moore has been weaving through the comic, namely Timothy’s flailing efforts to figure out how to market a brand of soda in the newly post-Soviet Russia. His explanation—a scene about generational transition between the generation that grew up in the USSR and younger children who have only ever known western consumerism—plays out as he fights to the death with himself.

And then he wakes up, alone in the hole, rubs his head, and walks away, conspicuously leaving his glasses behind. He walks into a small shop, and buys a can of soda—consciously and deliberately not the brand he’s just solved an advertising campaign for. The camera pulls back again, and a final bit of narration explains that “there’s a new yolk in the blown egg. There’s a new pulse in the scraped womb. Everything is pregnant. Into the morning, unnoticed, I slip from the scene of the crime,” this final sentence delivered over a wide shot in which a bicycle, car, train, and airplane are all visible.

As Moore explains it, “at the end of this battle he a different person. He has fused these two parts of himself into a whole, integrated person. Consequently, he no longer cares about the advertising for Flite… he has solved the problem that tortured him all through the book, but he has done it in such a way that the original problem turned into something totally irrelevant to the new person he’d become.” Moore offers this as part of a sprawling and lengthy commentary on the book—Moore suggests that Timothy Hole’s conflict is analogous to nations like the US and UK confronting the crimes of empire, which he sees as fundamental to dismantling empire because “Empires may only survive if they forget. They can only live with themselves if, concerning the moment when they committed the massacre or invaded another country and suppressed its citizen’s rights, they decide to forget all that, rewrite the history and say ’This never happened, it was a long time ago, and it doesn’t matter now, because things wer different and people didn’t know the things they know now.’ Bullshit. Be it as individuals or as a culture, we cannot make a step forward into a viable future as long as we are not capable of bearing the overwhelming weight of the dark side of our past.”

With hindsight, one can clearly see what Moore was doing here—the way in which, across his post-Watchmen projects, with Evey’s rain soaked apotheosis, the clarifying insight of the Mandelbrot set, and now this murder-suicide-ascension, Moore was meticulously summoning the magical insight that would strike him just two years after the publication of A Small Killing, a five year chrysalis he was rapidly preparing to break free of.

November 19, 2023 @ 5:21 pm

“The Tide Comes Crashing In” and “Cargo-Cult Recreation of an Imagined Life”