Chapter Four: Time as a Record Player (Watchmaker)

It is January, 1988. Alan Moore is thirty-three, and writing the introduction to the collected edition of Watchmen. His relationship with the publisher is in tatters, a fact he alludes to only vaguely when he notes that it is “the very last work that I expect to be doing upon Watchmen for the foreseeable future.” He looks back to 1984, when the idea originated, and the giddy enthusiasm of it all. And yet there is something he cannot quite locate in this. He notes that at the start “we wanted to do a novel and unusual super-hero comic that allowed us the opportunity to try out a few new storytelling ideas along the way. What we ended up with was substantially more than that.” But he cannot pin down the transition. Instead he describes a growing realization of the story’s complexity and scale, but without a sense that the realization had an end point. Instead, “there was the mounting suspicion (at least on my part) that we might have bitten off more than we could chew, that we might not be able to resolve all these momentous strands of narrative and meaning that seemed to be springing up wherever we looked, that we might be left at the end of the day with a big, messy, steaming bowl of semiotic spaghetti.” But even now, in 1988, Moore is lost in the process, saying that it is only now, in writing the introduction, that he realizes “how dazed a state I’d spent that year in, as if I’d been slam dancing with a bunch of rhinos and the concussion was only just starting to clear up,” a claim that oddly undercuts itself; the daze clearly extending beyond the year, simultaneously located “now, twelve months after” he finished the final script and in the past, as indicated by the past tense in the concussion metaphor.

It is January, 1988. Alan Moore is thirty-three, and writing the introduction to the collected edition of Watchmen. His relationship with the publisher is in tatters, a fact he alludes to only vaguely when he notes that it is “the very last work that I expect to be doing upon Watchmen for the foreseeable future.” He looks back to 1984, when the idea originated, and the giddy enthusiasm of it all. And yet there is something he cannot quite locate in this. He notes that at the start “we wanted to do a novel and unusual super-hero comic that allowed us the opportunity to try out a few new storytelling ideas along the way. What we ended up with was substantially more than that.” But he cannot pin down the transition. Instead he describes a growing realization of the story’s complexity and scale, but without a sense that the realization had an end point. Instead, “there was the mounting suspicion (at least on my part) that we might have bitten off more than we could chew, that we might not be able to resolve all these momentous strands of narrative and meaning that seemed to be springing up wherever we looked, that we might be left at the end of the day with a big, messy, steaming bowl of semiotic spaghetti.” But even now, in 1988, Moore is lost in the process, saying that it is only now, in writing the introduction, that he realizes “how dazed a state I’d spent that year in, as if I’d been slam dancing with a bunch of rhinos and the concussion was only just starting to clear up,” a claim that oddly undercuts itself; the daze clearly extending beyond the year, simultaneously located “now, twelve months after” he finished the final script and in the past, as indicated by the past tense in the concussion metaphor.

A similar temporal ambivalence exists in the previously discussed description of how his “nostalgia for the [superhero] genre cracked and shattered somewhere along the way and all the sweet old musk inside just leaked out and evaporated,” a statement in which Moore is clearly lying, albeit as much to himself as the reader, the description of the “sweet old musk” evoking precisely what he says he has lost, so that the sentence offers the very experience it exists to reject. Moore casts superheroes away, but in doing so only draws them back in, a tension implicit in the very idea of nostalgia, which is of course an intense feeling for a thing that one is not actually experiencing at the time. He is nostalgic for his nostalgia, relishing in the scent of its memory even as he pushes the genre away, grimly certain in the necessity of all his burnt bridges. The “disappointment when I learned that we couldn’t use the Charlton characters after all” mixes in his prose with the bitter taste of his falling out with DC.

A similar temporal ambivalence exists in the previously discussed description of how his “nostalgia for the [superhero] genre cracked and shattered somewhere along the way and all the sweet old musk inside just leaked out and evaporated,” a statement in which Moore is clearly lying, albeit as much to himself as the reader, the description of the “sweet old musk” evoking precisely what he says he has lost, so that the sentence offers the very experience it exists to reject. Moore casts superheroes away, but in doing so only draws them back in, a tension implicit in the very idea of nostalgia, which is of course an intense feeling for a thing that one is not actually experiencing at the time. He is nostalgic for his nostalgia, relishing in the scent of its memory even as he pushes the genre away, grimly certain in the necessity of all his burnt bridges. The “disappointment when I learned that we couldn’t use the Charlton characters after all” mixes in his prose with the bitter taste of his falling out with DC.

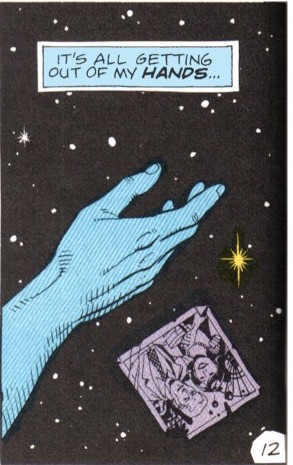

But more important than the way these things slide away from him is what he is looking for in amidst the rubble: “any sort of perspective upon what it was we actually did.” He does not find it in the essay. In some ways he never finds it anywhere. Watchmen simply proves to be the exact sort of semiotic spaghetti he feared, slithering through his fingers whenever he tried to grasp at it. Certainly his subsequent accounts of it only become more tinged by his deepening antipathy towards the work’s publisher. And it is hardly surprising that his memory does not improve with time; they generally don’t, after all. But all the same, he is perpetually unable to ever quite answer the question “what were you trying to do with Watchmen” in a definite way. For all that the trajectories of influence and thought that shape Watchmen can be traced and understood, it remains strangely difficult to articulate a statement of intent.

But more important than the way these things slide away from him is what he is looking for in amidst the rubble: “any sort of perspective upon what it was we actually did.” He does not find it in the essay. In some ways he never finds it anywhere. Watchmen simply proves to be the exact sort of semiotic spaghetti he feared, slithering through his fingers whenever he tried to grasp at it. Certainly his subsequent accounts of it only become more tinged by his deepening antipathy towards the work’s publisher. And it is hardly surprising that his memory does not improve with time; they generally don’t, after all. But all the same, he is perpetually unable to ever quite answer the question “what were you trying to do with Watchmen” in a definite way. For all that the trajectories of influence and thought that shape Watchmen can be traced and understood, it remains strangely difficult to articulate a statement of intent.

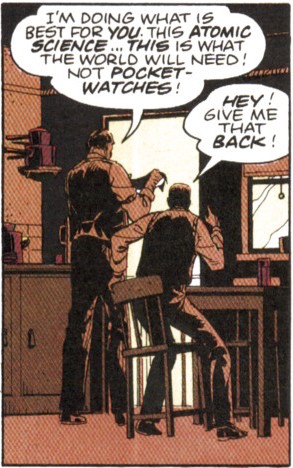

It is the summer of 1966. Alan Moore is twelve, and trawling the seaside bookstores in Yarmouth in search of comics he has not read. His day’s haul brings back two – an anthology of Mad comics that includes Wally Wood and Harvey Kurtzman’s “Superduperman,” and a collection of Mick Anglo’s Marvelman comics. That night, back in his caravan, he reads one, then the other. The ideas blur in his head. Kurtzman’s humor works, he reasons, because he applies real-world logic to the superhero genre. But the process doesn’t just have to work for humor, he realizes. “You could also, with a turn of the screw, make something that was quite startling, sort of dramatic and powerful.” He imagines doing so with Mick Anglo’s simple and innocent character, imagining Marvelman having forgotten his magic word.

It is the summer of 1966. Alan Moore is twelve, and trawling the seaside bookstores in Yarmouth in search of comics he has not read. His day’s haul brings back two – an anthology of Mad comics that includes Wally Wood and Harvey Kurtzman’s “Superduperman,” and a collection of Mick Anglo’s Marvelman comics. That night, back in his caravan, he reads one, then the other. The ideas blur in his head. Kurtzman’s humor works, he reasons, because he applies real-world logic to the superhero genre. But the process doesn’t just have to work for humor, he realizes. “You could also, with a turn of the screw, make something that was quite startling, sort of dramatic and powerful.” He imagines doing so with Mick Anglo’s simple and innocent character, imagining Marvelman having forgotten his magic word.

It is 1980 and Moore is reworking his childhood idea into a pitch for Dez Skinn.

It is late 1986 and Moore, his relationship with DC fraying rapidly, is on the phone with Neil Gaiman offering him the opportunity to take over the comic, now called Miracleman and published by Eclipse.

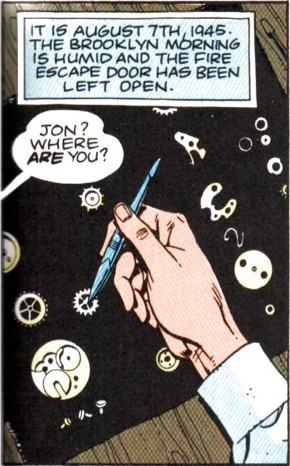

The gears turn in his mind. He wakes up the next day and steps outside. He does not realize that the world has changed forever. No one does. Twenty years later, the first issue of Watchmen is released. Twelve years before, the legal dispute between DC and Fawcett satirized by Kurtzman and Wood forces Len Miller to have Mick Anglo create a replacement character for the Captain Marvel comics he had been publishing. Moore breathes in the salty air, and goes about his annual family vacation.

The gears turn in his mind. He wakes up the next day and steps outside. He does not realize that the world has changed forever. No one does. Twenty years later, the first issue of Watchmen is released. Twelve years before, the legal dispute between DC and Fawcett satirized by Kurtzman and Wood forces Len Miller to have Mick Anglo create a replacement character for the Captain Marvel comics he had been publishing. Moore breathes in the salty air, and goes about his annual family vacation.

It’s May of 1983. Alan Moore is almost thirty. He is sitting down to dinner with Phyllis, Leah, and Amber when the phone rings. Len Wein, an ocean away, is offering him the opportunity to write Swamp Thing. Moore assumes that David Lloyd is playing a practical joke on him. Persuaded otherwise, he starts work as per what is, by this point, his tried and true method, examining the character’s origin and premise for roads not taken that he can explore for stories, eventually settling on a quirk of the character’s origin. The result is an unexpected hit, with the comic quickly going from the lowest performer in DC’s stable to a widely-acclaimed hit, and generating even more work for Moore. The result is life-changing, with each issue he does for DC earning him as much as all his monthly commitments in the UK market combined. It is a level of financial security he has never imagined before, and scarcely could have. Gradually, he readjusts his output, winding down his UK commitments and working almost entirely in the American market.

It’s May of 1983. Alan Moore is almost thirty. He is sitting down to dinner with Phyllis, Leah, and Amber when the phone rings. Len Wein, an ocean away, is offering him the opportunity to write Swamp Thing. Moore assumes that David Lloyd is playing a practical joke on him. Persuaded otherwise, he starts work as per what is, by this point, his tried and true method, examining the character’s origin and premise for roads not taken that he can explore for stories, eventually settling on a quirk of the character’s origin. The result is an unexpected hit, with the comic quickly going from the lowest performer in DC’s stable to a widely-acclaimed hit, and generating even more work for Moore. The result is life-changing, with each issue he does for DC earning him as much as all his monthly commitments in the UK market combined. It is a level of financial security he has never imagined before, and scarcely could have. Gradually, he readjusts his output, winding down his UK commitments and working almost entirely in the American market.

It’s July of 2012, and Len Wein is calling Alan Moore selfish for his stance on Before Watchmen, claiming that if he’d viewed Swamp Thing that way Moore would never have had a career.

It’s spring of 1978. Alan Moore is twenty-four. His attempt at a comics career, encapsulated in the doomed and over-baroque Sun-Dodgers, has gone nowhere. He is a new father, living on the dole, trying to figure out how to write comics. Running out of tightrope to walk, he asks his best friend, Steve Moore, for help. He is told to scale down his ambition, advised that publications like 2000 AD (to which he had imagined pitching Sun-Dodgers) would not take pitches for ongoing series from writers who had not previously proven themselves with short work first. Moore refocuses, sending a series of pitches for the magazine’s Future Shocks feature, consisting of short sci-fi stories with generally humorous twist endings (the first, in fact, having been written by Steve Moore). This too proves slow, and for months Moore is left writing and drawing comic strips for Sounds and a local paper, at times hunching over an old Ottoman trunk because the heating had gone off, but eventually he finally breaks through. Moore eventually credits the discipline acquired doing short comics as key to his writing, advising it as the starting point for any aspiring comics writer.

It’s spring of 1978. Alan Moore is twenty-four. His attempt at a comics career, encapsulated in the doomed and over-baroque Sun-Dodgers, has gone nowhere. He is a new father, living on the dole, trying to figure out how to write comics. Running out of tightrope to walk, he asks his best friend, Steve Moore, for help. He is told to scale down his ambition, advised that publications like 2000 AD (to which he had imagined pitching Sun-Dodgers) would not take pitches for ongoing series from writers who had not previously proven themselves with short work first. Moore refocuses, sending a series of pitches for the magazine’s Future Shocks feature, consisting of short sci-fi stories with generally humorous twist endings (the first, in fact, having been written by Steve Moore). This too proves slow, and for months Moore is left writing and drawing comic strips for Sounds and a local paper, at times hunching over an old Ottoman trunk because the heating had gone off, but eventually he finally breaks through. Moore eventually credits the discipline acquired doing short comics as key to his writing, advising it as the starting point for any aspiring comics writer.

It’s January 7th, 1994. Alan Moore is forty, not two months past impulsively declaring himself to be a magician. He is in London, on Shooter’s Hill, visiting Steve Moore. A psilocybin-infused conversation about the Burroughs/Glysin cut-up method as alchemical process gives way abruptly to spiritual vision. The room itself opens and unfolds into some higher space, the chain of conversation – “an idea that turns out to be connected to another, then another, and the discourse makes its labouring progress upward from one concept to the next” until it reaches some divinity that reveals itself in spite of its unknowability. The city of London opens up to him, its psychogeographic resonances becoming visible, all its ideas and history a tangible, real part of it. Through all of it, there is one strange certainty – the sense that the godhead he has inadvertently scraped against is serpentine in form, “dream-spine, knobbly with conceptuual vertebrae but smooth as viscous liquid in its movement, living chain of muscular and dangerous notion, looping and recursive thought-meat winding, coiling back and forth upon itself, a current dragging helpless consciousness along its length in rippling peristalsis.”

It’s January 7th, 1994. Alan Moore is forty, not two months past impulsively declaring himself to be a magician. He is in London, on Shooter’s Hill, visiting Steve Moore. A psilocybin-infused conversation about the Burroughs/Glysin cut-up method as alchemical process gives way abruptly to spiritual vision. The room itself opens and unfolds into some higher space, the chain of conversation – “an idea that turns out to be connected to another, then another, and the discourse makes its labouring progress upward from one concept to the next” until it reaches some divinity that reveals itself in spite of its unknowability. The city of London opens up to him, its psychogeographic resonances becoming visible, all its ideas and history a tangible, real part of it. Through all of it, there is one strange certainty – the sense that the godhead he has inadvertently scraped against is serpentine in form, “dream-spine, knobbly with conceptuual vertebrae but smooth as viscous liquid in its movement, living chain of muscular and dangerous notion, looping and recursive thought-meat winding, coiling back and forth upon itself, a current dragging helpless consciousness along its length in rippling peristalsis.”

It’s July 16th, 1994. Alan Moore is on stage at the St. Bride Foundation Institute and Library alongside David J, performing as part of a three-night event organized by Iain Sinclair. It is his first public magical working, eventually released on CD as The Moon and Serpent Grand Egyptian Theatre of Marvels. He speaks of Glycon, the serpent he encountered on Shooter’s Hill just 190 days earlier, describing “the parched air oiled with myrrh, a depthless, lidless dark before awakening, but pin lit, scented, pearled in thousands, naked brainstem, arid spine of lightning, fossil stripes the white dunes outside time, his belly filled with understanding, jewel, and poison.”

It’s July 16th, 1994. Alan Moore is on stage at the St. Bride Foundation Institute and Library alongside David J, performing as part of a three-night event organized by Iain Sinclair. It is his first public magical working, eventually released on CD as The Moon and Serpent Grand Egyptian Theatre of Marvels. He speaks of Glycon, the serpent he encountered on Shooter’s Hill just 190 days earlier, describing “the parched air oiled with myrrh, a depthless, lidless dark before awakening, but pin lit, scented, pearled in thousands, naked brainstem, arid spine of lightning, fossil stripes the white dunes outside time, his belly filled with understanding, jewel, and poison.”

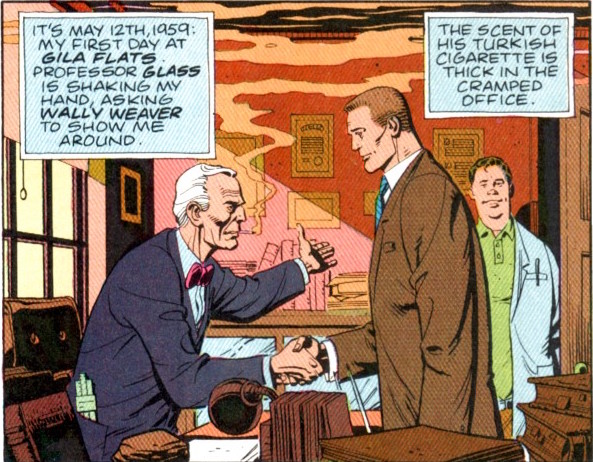

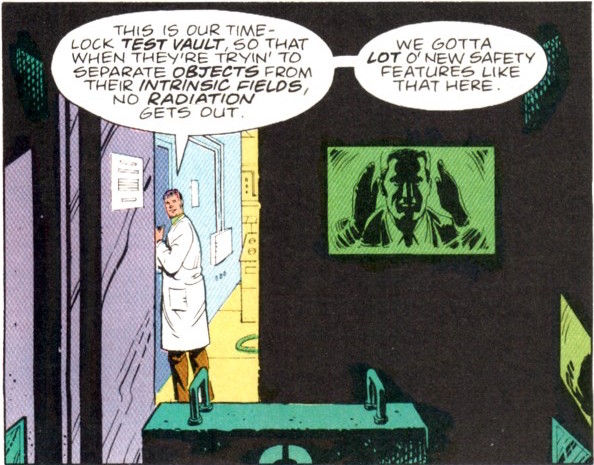

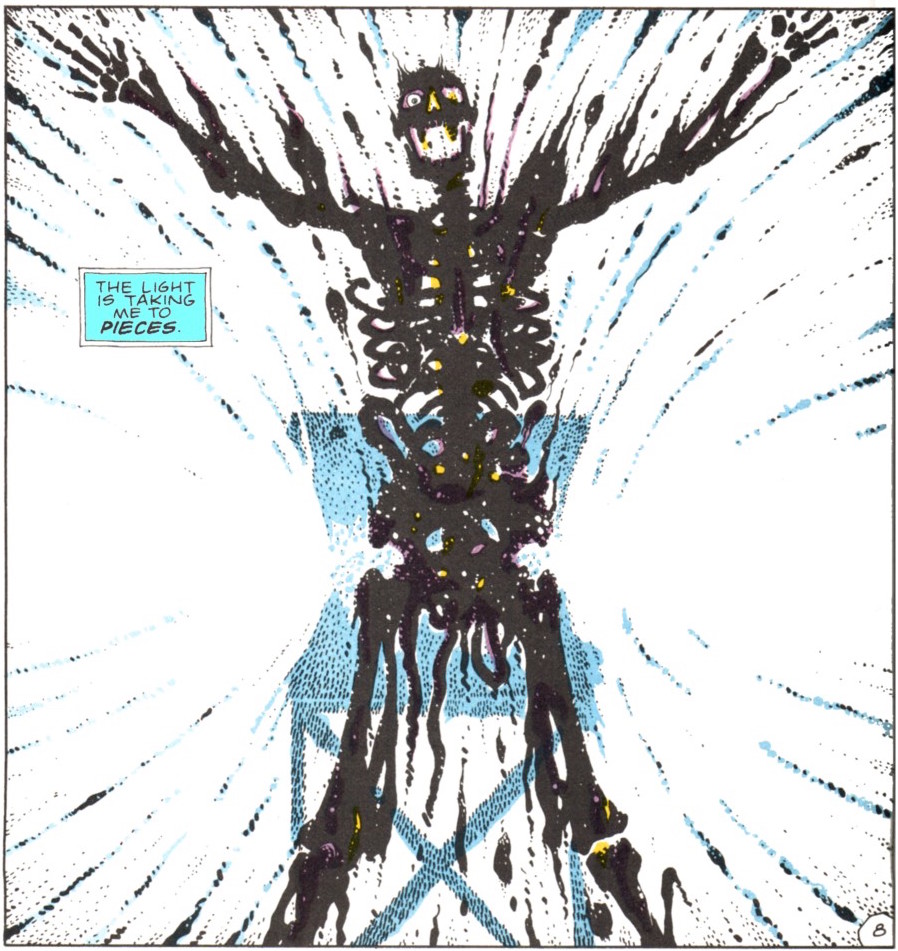

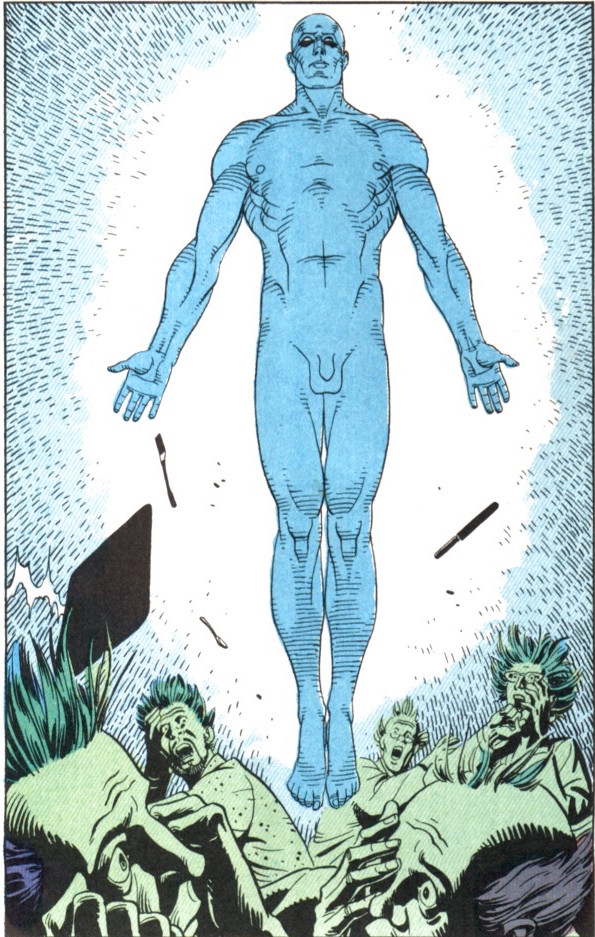

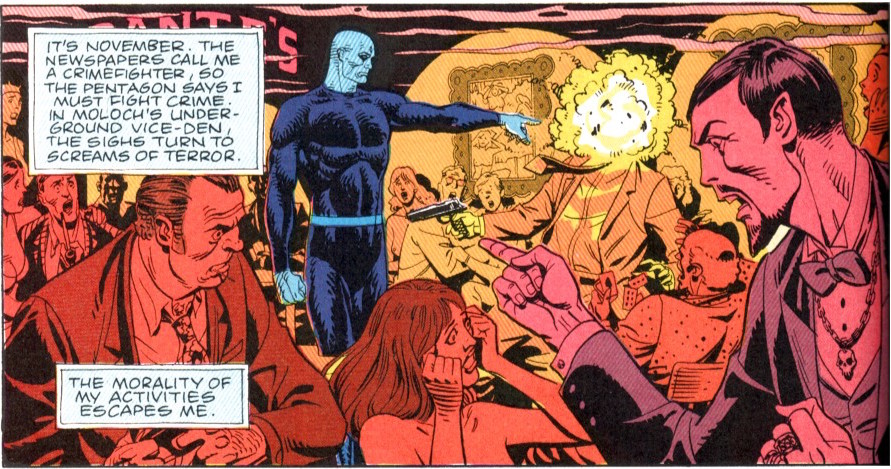

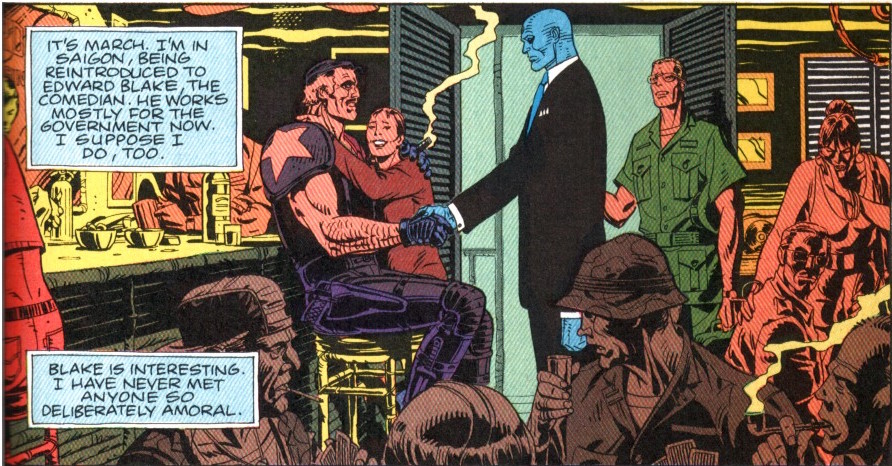

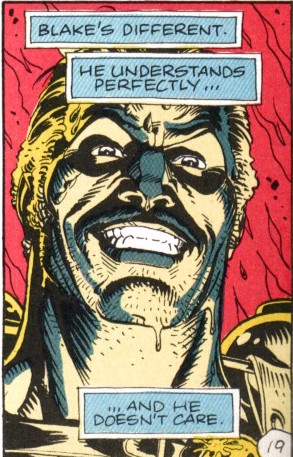

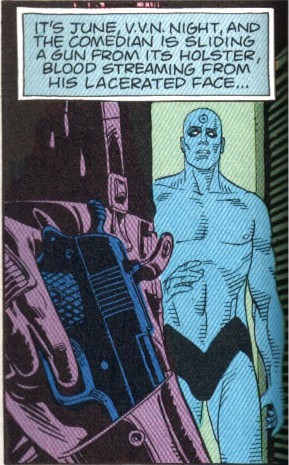

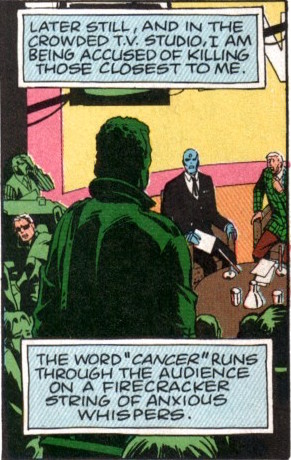

It’s late spring, 1984. Alan Moore is thirty-one, and starting work on Who Killed the Peacemaker, studiously dismantling the Charlton heroes and reassembling them to see what emerges. It’s a process he’s done many times before, creating “serious” or “realistic” takes on superheroes by picking at stray details of them, but here his aim is wider, based around the idea of a longstanding superhero continuity. One idea begins to lead to another, his old familiar process slowly approaching some larger revelation – some truth about the superhero fantasy and its relationship to history and power that can only fit into the specific narrative devices he is imagining. He does not know what he is doing; merely how to do it. There is no way to know what he is doing. There is only the work.

It’s late spring, 1984. Alan Moore is thirty-one, and starting work on Who Killed the Peacemaker, studiously dismantling the Charlton heroes and reassembling them to see what emerges. It’s a process he’s done many times before, creating “serious” or “realistic” takes on superheroes by picking at stray details of them, but here his aim is wider, based around the idea of a longstanding superhero continuity. One idea begins to lead to another, his old familiar process slowly approaching some larger revelation – some truth about the superhero fantasy and its relationship to history and power that can only fit into the specific narrative devices he is imagining. He does not know what he is doing; merely how to do it. There is no way to know what he is doing. There is only the work.

It’s 1980, and he is taking apart Marvelman.

It’s May of 1983, and he is contemplating Swamp Thing’s origin.

It’s summer, 1992. Alan Moore is thirty-eight. Just a few years out from the twin smoldering wreckages of Big Numbers and his first marriage, he takes a call from Jim Valentino at Image Comics. Moore is unimpressed with the Image output, thinking, “I’ve been away for five years, and comics have turned into some bizarre super-steroid-mutant hybrid that I’ve got no familiarity with at all,” but the business model of Image appeals to him, and the failure of Big Numbers along with a relatively fallow period in Moore’s output means he needs the money, and so he throws himself into “teaching myself this new language and trying to understand this new audience.” He ends up creating 1963 with Steve Bissette and Rick Veitch, a colorful pastiche of vintage Marvel comics written in explicit contrast to the post-Watchmen style (largely embodied by Image itself) of violent and cynical comics.

It’s summer, 1992. Alan Moore is thirty-eight. Just a few years out from the twin smoldering wreckages of Big Numbers and his first marriage, he takes a call from Jim Valentino at Image Comics. Moore is unimpressed with the Image output, thinking, “I’ve been away for five years, and comics have turned into some bizarre super-steroid-mutant hybrid that I’ve got no familiarity with at all,” but the business model of Image appeals to him, and the failure of Big Numbers along with a relatively fallow period in Moore’s output means he needs the money, and so he throws himself into “teaching myself this new language and trying to understand this new audience.” He ends up creating 1963 with Steve Bissette and Rick Veitch, a colorful pastiche of vintage Marvel comics written in explicit contrast to the post-Watchmen style (largely embodied by Image itself) of violent and cynical comics.

It’s 1996, and Alan Moore is calling Steve Bissette to end their friendship over comments Bissette made in an interview with The Comics Journal, including some suggesting Moore had lost interest in 1963.

It’s 2010, and the last hope that the final installment of the project, an intended crossover between the 1963 characters and the rest of the Image line will ever come out finally sputters out.

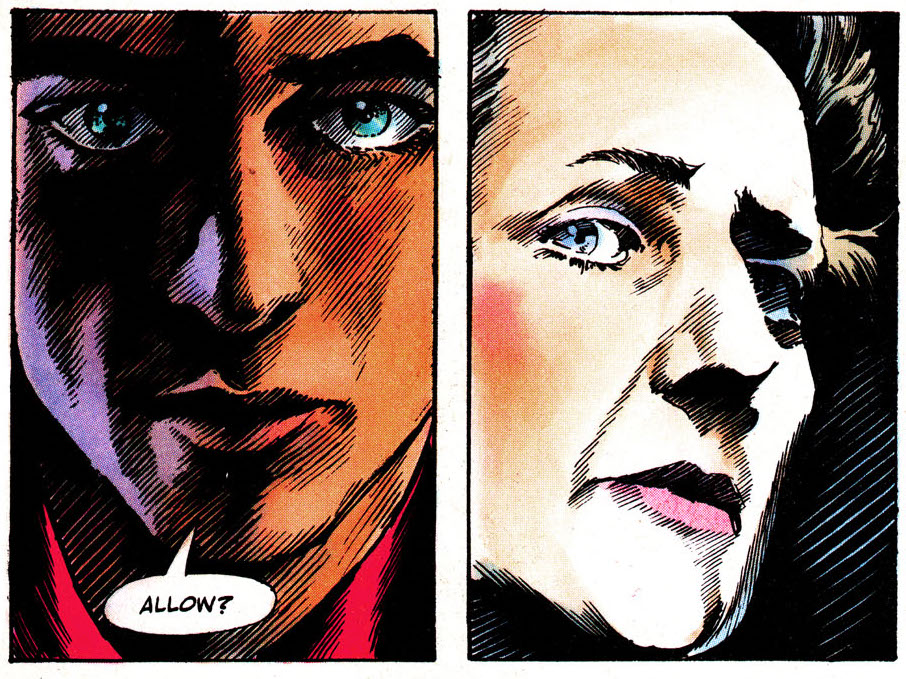

It’s June of 2010. Alan Moore is fifty-six, and having his last conversation with Dave Gibbons. Their relationship had already been strained after Gibbons had conveyed a message from DC suggesting that Moore would be “quietly compliant” about the Tales of the Black Freighter motion comic, a phrase Moore took in the context of him having previously asked DC not to play games with Steve Moore (who had previously novelized the V for Vendetta film) as his brother was dying, especially after DC spiked Steve Moore’s planned Watchmen novelization when Moore was less quiet and compliant than assumed. Following this Moore had asked Gibbons to not talk to him about Watchmen anymore for the sake of their friendship. “Alan, got a few minutes? I just want to talk to you about Watchmen,” Gibbons said, before presenting a series of offers from DC regarding either returning the rights to Watchmen or officially buying Moore out in exchange for his sanction of Before Watchmen.

It’s June of 2010. Alan Moore is fifty-six, and having his last conversation with Dave Gibbons. Their relationship had already been strained after Gibbons had conveyed a message from DC suggesting that Moore would be “quietly compliant” about the Tales of the Black Freighter motion comic, a phrase Moore took in the context of him having previously asked DC not to play games with Steve Moore (who had previously novelized the V for Vendetta film) as his brother was dying, especially after DC spiked Steve Moore’s planned Watchmen novelization when Moore was less quiet and compliant than assumed. Following this Moore had asked Gibbons to not talk to him about Watchmen anymore for the sake of their friendship. “Alan, got a few minutes? I just want to talk to you about Watchmen,” Gibbons said, before presenting a series of offers from DC regarding either returning the rights to Watchmen or officially buying Moore out in exchange for his sanction of Before Watchmen.

It’s Late 2001. Alan Moore is forty-eight, and being visited in Northampton by Steve Moore. He has come in order to seek clarity regarding his ongoing sexual relationship with the moon goddess Selene, attempting to discern whether she is a sign of his own madness or not by asking his friend whether he can see her too. He sits on his friends sofa and begins to chant. Moore describes the experience: “oh fuck she’s blue, electric ultra-violet blue on her illuminated contours, see-through in the shadows like a special-effects hologram. She’s riding him, she’s straddling his lap, her narrow back is turned towards me and she’s nothing like her picture, nothing like the way he sees her and describes her.” The existence of his lover verified, Moore returns home to Shooter’s Hill the next morning.

It’s Late 2001. Alan Moore is forty-eight, and being visited in Northampton by Steve Moore. He has come in order to seek clarity regarding his ongoing sexual relationship with the moon goddess Selene, attempting to discern whether she is a sign of his own madness or not by asking his friend whether he can see her too. He sits on his friends sofa and begins to chant. Moore describes the experience: “oh fuck she’s blue, electric ultra-violet blue on her illuminated contours, see-through in the shadows like a special-effects hologram. She’s riding him, she’s straddling his lap, her narrow back is turned towards me and she’s nothing like her picture, nothing like the way he sees her and describes her.” The existence of his lover verified, Moore returns home to Shooter’s Hill the next morning.

It’s March 16th, 2014. Steve Moore passes away in the same house in which he was born.

It’s March 17th, 2014. Steve Moore is seen alive by his neighbors. Alan Moore describes this as “kind of annoying, as neither Steve nor myself had any axe to grind for ghosts,” although he appreciates the Algernon Blackwood nature of the tale.

It’s August 1st, 1985. Alan Moore is thirty-two, and on his second trip to the United States to attend San Diego Comic-Con, where he meets his Miracleman editor cat yronwode for the first and only time, as well as appearing on a panel with Jack Kirby and Frank Miller – his second meeting with the latter and his first and only meeting with the former. (It is an awkward, tense panel, with Kirby’s argument with Marvel over getting his original art back hanging over proceedings. he only gets to speak to his childhood idol briefly, describing him later as “this sort of walnut colored little guy with a shackle of white hair and these craggy Kirby drawn features” who nevertheless has an “aura” around him. Kirby praises his two panel-mates, telling them, “you kids, I think you’re great. You kids, what you’ve done is terrific. I really want to thank you.”) It looks for all the world like a meeting of the greatest visionaries in comics; an all-time legend and two of the brightest talents of the future.

It’s August 1st, 1985. Alan Moore is thirty-two, and on his second trip to the United States to attend San Diego Comic-Con, where he meets his Miracleman editor cat yronwode for the first and only time, as well as appearing on a panel with Jack Kirby and Frank Miller – his second meeting with the latter and his first and only meeting with the former. (It is an awkward, tense panel, with Kirby’s argument with Marvel over getting his original art back hanging over proceedings. he only gets to speak to his childhood idol briefly, describing him later as “this sort of walnut colored little guy with a shackle of white hair and these craggy Kirby drawn features” who nevertheless has an “aura” around him. Kirby praises his two panel-mates, telling them, “you kids, I think you’re great. You kids, what you’ve done is terrific. I really want to thank you.”) It looks for all the world like a meeting of the greatest visionaries in comics; an all-time legend and two of the brightest talents of the future.

It’s October 1987. Alan Moore is thirty-three, and taking his third and final trip to the United States, accompanied by Debbie Delano. He is a guest of the Christic Institute, a Washington DC law firm that has asked him to compile the extensive research they’ve done into the unsavory history of the CIA into a comic book. It is an appalling history; Moore eventually ends up describing various CIA operations in terms of the number of swimming pools that could have been filled with the blood of the deceased. Moore sifts through the evidence, tracing conspiracy after conspiracy, watching the way they trip over each other and stack upon each other. He will later describe his realization in blunt and chilling terms: “the world is rudderless.”

It’s October 1987. Alan Moore is thirty-three, and taking his third and final trip to the United States, accompanied by Debbie Delano. He is a guest of the Christic Institute, a Washington DC law firm that has asked him to compile the extensive research they’ve done into the unsavory history of the CIA into a comic book. It is an appalling history; Moore eventually ends up describing various CIA operations in terms of the number of swimming pools that could have been filled with the blood of the deceased. Moore sifts through the evidence, tracing conspiracy after conspiracy, watching the way they trip over each other and stack upon each other. He will later describe his realization in blunt and chilling terms: “the world is rudderless.”

It’s December 2nd, 2011. Alan Moore is fifty-eight, and speaking to Honest Publishing. He is asked about Frank Miller’s then-recent comments calling the Occupy movement “spoiled brats who should stop getting in the way of working people and find jobs for themselves” who “can do nothing but harm America.” Moore decries his apparently former friend, complaining that “there has probably been a rather unpleasant sensibility apparent in Frank Miller’s work for quite a long time,” complaining of the overall right-wing slant of the comics industry and stressing that “me and Frank Miller have diametrically opposing views upon all sorts of things.”

It’s December 2nd, 2011. Alan Moore is fifty-eight, and speaking to Honest Publishing. He is asked about Frank Miller’s then-recent comments calling the Occupy movement “spoiled brats who should stop getting in the way of working people and find jobs for themselves” who “can do nothing but harm America.” Moore decries his apparently former friend, complaining that “there has probably been a rather unpleasant sensibility apparent in Frank Miller’s work for quite a long time,” complaining of the overall right-wing slant of the comics industry and stressing that “me and Frank Miller have diametrically opposing views upon all sorts of things.”

It’s 1986, and Alan Moore is taking a phone call from Frank Miller about DC’s planned ratings system.

It’s early 1987, and Moore is deciding to walk away from the company for good.

It’s October 1987 Moore is sitting down to dinner after a Glasgow signing to promote Watchmen. At the table is Grant Morrison, a neophyte comics writer. It is the only meeting between them that Moore recalls, although he had given Morrison advice at a 1983 Glasgow comic mart when Morrison was on the cusp of transitioning from a failed rock star to a successful comics writer. Moore will eventually, to Morrison’s chagrin, describe him as an “aspiring” comics writer at the time of this meeting, one of many swipes he will take at Morrison over the years. They talk about vegetarianism. (“Sometimes you can’t live with the contradictions, Grant,” Morrison recalls him saying.)

It’s October 1987 Moore is sitting down to dinner after a Glasgow signing to promote Watchmen. At the table is Grant Morrison, a neophyte comics writer. It is the only meeting between them that Moore recalls, although he had given Morrison advice at a 1983 Glasgow comic mart when Morrison was on the cusp of transitioning from a failed rock star to a successful comics writer. Moore will eventually, to Morrison’s chagrin, describe him as an “aspiring” comics writer at the time of this meeting, one of many swipes he will take at Morrison over the years. They talk about vegetarianism. (“Sometimes you can’t live with the contradictions, Grant,” Morrison recalls him saying.)

It’s Christmas 2013. Alan Moore, in the course of an interview, offers the stunning transition, “this, I think, leaves us only with the herpes-like persistence of Grant Morrison” before launching into a four-thousand word account of his history with Morrison and concluding that he would prefer if “admirers of Grant Morrison’s work would please stop reading mine, as I don’t think it fair that my respect and affection for my own readership should be compromised in any way by people that I largely believe to be shallow and undiscriminating.”

It’s August, 1998. Alan Moore is forty-four, and on holiday in Wales, having just signed the contracts to create a new line of superheroes for Jim Lee and Scott Dunbier’s Wildstorm imprint. Dunbier and Lee fly out on short notice to do Moore the courtesy of telling him in person that the company has just been sold to DC. Moore, noting that the deal was struck almost immediately after the contracts were signed, and that DC had previously tried to buy Rob Liefeld’s Awesome Comics in order to re-acquire Moore. Despite his intense misgivings (Moore described DC as “a really weird, rich stalker girlfriend”), Moore was unwilling to take the contracted work away from his artistic collaborators, and so agreed to continue producing the comics, albeit with a firm editorial firewall between himself and DC; indeed, a company called Firewall was created to serve as the nominal entity cutting Moore’s checks so that DC’s name wouldn’t even appear on them.

It’s August, 1998. Alan Moore is forty-four, and on holiday in Wales, having just signed the contracts to create a new line of superheroes for Jim Lee and Scott Dunbier’s Wildstorm imprint. Dunbier and Lee fly out on short notice to do Moore the courtesy of telling him in person that the company has just been sold to DC. Moore, noting that the deal was struck almost immediately after the contracts were signed, and that DC had previously tried to buy Rob Liefeld’s Awesome Comics in order to re-acquire Moore. Despite his intense misgivings (Moore described DC as “a really weird, rich stalker girlfriend”), Moore was unwilling to take the contracted work away from his artistic collaborators, and so agreed to continue producing the comics, albeit with a firm editorial firewall between himself and DC; indeed, a company called Firewall was created to serve as the nominal entity cutting Moore’s checks so that DC’s name wouldn’t even appear on them.

It’s April 2000 and Paul Levitz, by now publisher at DC Comics, is breaking the agreement, stepping in and ordering the entire print run of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen #5 pulped and blocking a story in Tomorrow Stories #8 over what Moore viewed as minor concerns.

It’s August 1984 and Paul Levitz is calling Moore his “greatest mistake.”

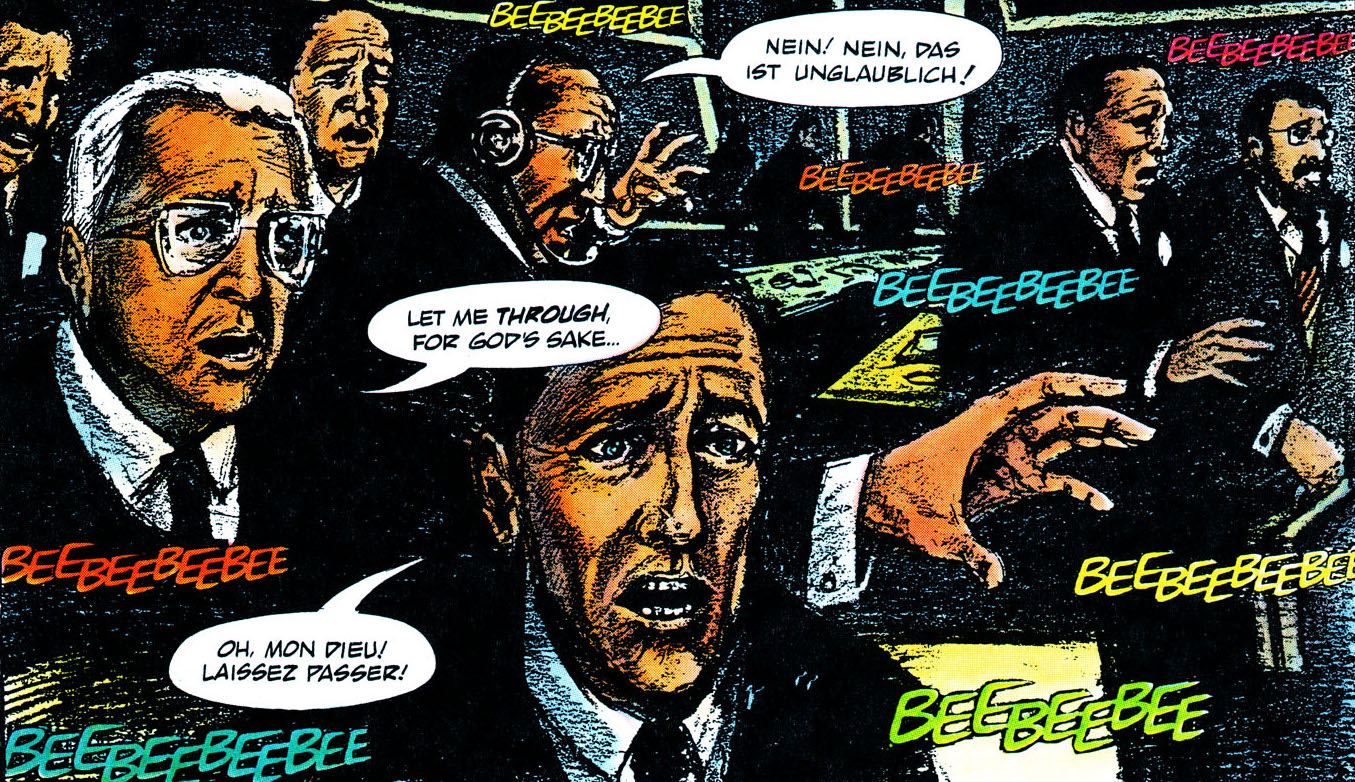

It’s November 29th, 1986. Alan Moore is thirty-three, and deep in the writing of Watchmen. He takes a phone call from Frank Miller, who informs him of a planned ratings system to be imposed by DC. Moore is incensed, not least because he’s aware that his work on Miracleman for Eclipse was one of the main things cited in the debates that led to this decision. His relationship with DC already fraying due to issues surrounding the Watchmen contract, Moore quickly signs on to a letter vowing to do no more work for DC over the issue. When DC backs down a few months later, Moore is perplexed to discover that he is the only creator who actually meant this in general, as opposed to as a negotiating tactic, and finds himself in the odd position of being one of the most bankable names in comics and no longer having a publisher.

It’s November 29th, 1986. Alan Moore is thirty-three, and deep in the writing of Watchmen. He takes a phone call from Frank Miller, who informs him of a planned ratings system to be imposed by DC. Moore is incensed, not least because he’s aware that his work on Miracleman for Eclipse was one of the main things cited in the debates that led to this decision. His relationship with DC already fraying due to issues surrounding the Watchmen contract, Moore quickly signs on to a letter vowing to do no more work for DC over the issue. When DC backs down a few months later, Moore is perplexed to discover that he is the only creator who actually meant this in general, as opposed to as a negotiating tactic, and finds himself in the odd position of being one of the most bankable names in comics and no longer having a publisher.

It is January, 1988, and Alan Moore done; all the Watchmen press tours and signings are completed. He finishes the introduction to the collected edition, another for the completed V for Vendetta a few months later. He is finished, free of whatever conceptual prison or labyrinth he had been walking in these past five years. He can choose his next project. He can choose not to have a next project. He can do whatever he wants, if only he can discern what that is.

It is January, 1988, and Alan Moore done; all the Watchmen press tours and signings are completed. He finishes the introduction to the collected edition, another for the completed V for Vendetta a few months later. He is finished, free of whatever conceptual prison or labyrinth he had been walking in these past five years. He can choose his next project. He can choose not to have a next project. He can do whatever he wants, if only he can discern what that is.

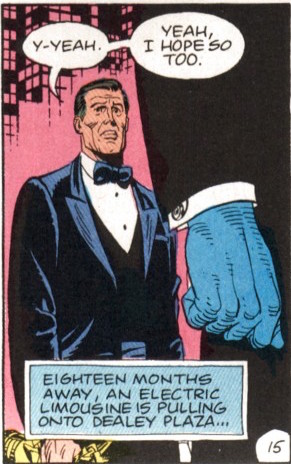

Had he been spoiling for a fight? Trying to prove a point? Was he just a chancing freelance chasing whatever muse flickered before him? What had his ideas meant? Where did they lead? How long had he been climbing the tail of the serpent before he realized it? And where was he actually going? Perhaps there are not answers to these questions. Perhaps Watchmen is less a thing that was done than a thing that happened; less a creation than an event. Perhaps, like the stroke of midnight on the clock printed on the back cover of every issue, it was simply a thing that history approached inexorably. A certainty that could no more have been engineered than it could have been prevented.

Had he been spoiling for a fight? Trying to prove a point? Was he just a chancing freelance chasing whatever muse flickered before him? What had his ideas meant? Where did they lead? How long had he been climbing the tail of the serpent before he realized it? And where was he actually going? Perhaps there are not answers to these questions. Perhaps Watchmen is less a thing that was done than a thing that happened; less a creation than an event. Perhaps, like the stroke of midnight on the clock printed on the back cover of every issue, it was simply a thing that history approached inexorably. A certainty that could no more have been engineered than it could have been prevented.

Alan Moore writes the sentence “Human or otherwise,” and signs his name. The collected edition of Watchmen comes into being, and exists immediately within Eternity. The clock ticks, then ticks again, and again, and again, and again.

Alan Moore writes the sentence “Human or otherwise,” and signs his name. The collected edition of Watchmen comes into being, and exists immediately within Eternity. The clock ticks, then ticks again, and again, and again, and again.

“I can’t fight, for god’s sake. I can’t fight anymore. Marcos told me to think of time as a record player, with the stylus tracing the present, while the past and future exist simultaneously… Neat little analogy, huh? I asked him what record it was, but he didn’t know… Hey, did you hear the one about the nuns?” – Grant Morrison, “The Checkmate Man”

{Impressively, Alan Moore’s second publisher for Marvelman/Miracleman was an even bigger trainwreck than his first. It is perhaps unsurprising, given this, to find out that Dez Skinn negotiated the bulk of the deal. The financial plan for Warrior had always involved selling the strips to foreign markets, and Skinn was determined to sell them as a package, reasoning that “strips like Spiral Path – which I put into an anthology alongside Shandor and Bojeffries Saga – were not the stars of the show,” but that Warrior would never have happened without them and that they deserved the same shot at foreign publication as the heavy-hitters like V for Vendetta and Laser Eraser and Pressbutton. But ironically, it wasn’t the lesser Warrior material that made selling the strips abroad a challenge, but the nominal crown jewel, Marvelman, as neither of the two biggest comics publishers would touch it. DC was the obvious first choice, since they were already having considerable success publishing Alan Moore in the US market, and were indeed interested, but Dick Giordano pointed out that there was simply no way that they could publish a comic called Marvelman, citing the number of problems they were already having with Captain Marvel, which they’d bought from the smoldering ruins of Fawcett and started publishing under the name Shazam! But the obvious second choice proved no better; Marvel wouldn’t touch it either, pointing out that if they were to publish a strip called Marvelman it would be read as representing the entire company, which was perhaps not quite what they wanted Moore’s psychologically damaged take on superheroes to do.

{Impressively, Alan Moore’s second publisher for Marvelman/Miracleman was an even bigger trainwreck than his first. It is perhaps unsurprising, given this, to find out that Dez Skinn negotiated the bulk of the deal. The financial plan for Warrior had always involved selling the strips to foreign markets, and Skinn was determined to sell them as a package, reasoning that “strips like Spiral Path – which I put into an anthology alongside Shandor and Bojeffries Saga – were not the stars of the show,” but that Warrior would never have happened without them and that they deserved the same shot at foreign publication as the heavy-hitters like V for Vendetta and Laser Eraser and Pressbutton. But ironically, it wasn’t the lesser Warrior material that made selling the strips abroad a challenge, but the nominal crown jewel, Marvelman, as neither of the two biggest comics publishers would touch it. DC was the obvious first choice, since they were already having considerable success publishing Alan Moore in the US market, and were indeed interested, but Dick Giordano pointed out that there was simply no way that they could publish a comic called Marvelman, citing the number of problems they were already having with Captain Marvel, which they’d bought from the smoldering ruins of Fawcett and started publishing under the name Shazam! But the obvious second choice proved no better; Marvel wouldn’t touch it either, pointing out that if they were to publish a strip called Marvelman it would be read as representing the entire company, which was perhaps not quite what they wanted Moore’s psychologically damaged take on superheroes to do.

That left smaller companies. Initially the plan was a company called Pacific Comics, but after contracts were signed and the first issue of Challenger, headlined by V for Vendetta, advertised Pacific abruptly went belly up in August of 1984, leaving all of the Warrior properties homeless once again. Ultimately they were acquired, alongside some other remnants of Pacific, by Eclipse Comics, created by siblings Jan and Dean Mullaney, but edited by cat yronwode (lack of capitalization per her wishes), a small publisher originally out of New York, but by this point run out of Guerneville California. But there were still other problems. Not only was Marvel uninterested in publishing Marvelman, they were uninterested in the idea of anyone else publishing him. This started with Marvel UK’s dispute with Skinn over the latter’s decision to break the informal truce they had by actually publishing a comic called Marvelman on the cover instead of featuring him inside Warrior, but rapidly spread to the US branch of the company.

In Moore’s telling, the figure at the heart of the dispute was Jim Shooter, who he characterizes as “one of these comic book industry führers,” which doesn’t actually rate very highly in the list of awful things Jim Shooter has been called by his fellow professionals. Moore was, to say the least, unhappy about this; in his view, Marvelman’s publication history extended further back than Timely/Atlas Comics’s renaming to Marvel, and there was no reason why he should have to change the name of an iconic British superhero to appease a company that had nothing to do with it. Still, he offered a compromise, proposing calling the book Kimota! in the same way that DC was calling their Captain Marvel book Shazam!, but was told by, as he puts it, “people who once meant something at Marvel Comics, and were all-powerful and supreme, and are now probably working in Blockbusters” that this was unacceptable as well. And so he pushed back, declaring that he would forbid reprints of any of his Captain Britain work if Marvel persisted, . As Moore recounts it, at this point industry legend Archie Goodwin stepped in, penning a letter to Shooter in which he appealed for him to “ease up” on Marvelman, which Shooter responded to by crumpling the letter up and tossing in a desk drawer, where it was allegedly found by his successor.

As with many stories recounted by Alan Moore, the details have the distinct sense of having been fiddled by one of the greatest storytellers of his generation. But regardless of whether Jim Shooter didn’t understand how to operate a trash can or not, the conflict with Marvel over the character’s name would have consequences above and beyond the inevitable capitulation and agreement to rename the character Miracleman (a name first proposed by Moore in his initial pitch to Dez Skinn as a suggestion in the event that the Marvelman rights proved troublesome, but ironically first publicly used as a blatant stand-in for Marvelman in the pages of Moore’s Captain Britain run, which means that technically they changed the character to one Marvel had a nominally stronger legal claim about, though nothing came of this detail). But it also led to the breakdown of Alan Moore and Alan Davis’s friendship when Moore carried through on his threat to block Captain Britain reprints. In Davis’s telling, “Alan hadn’t bothered telling me that he’d refused to allow Captain Britain to be reprinted. I found out, sort of like, five months after.” Incensed, Davis decided to retaliate by vetoing reprints of his work on Marvelman.

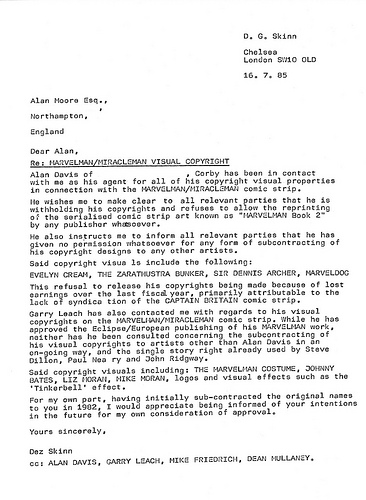

Faced with the withdrawal of the artist on what was to be issues #2-6 of their reprints, yronwode did what any responsible editor at a comics company firmly committed to creators’ rights would do in this situation, namely illegally reprint the work anyway. In Davis’s blunt account, “Eclipse, Dez, and Alan all ignored my protests/refusals and my work was stolen,” although the matter is at least somewhat more complex than that; in fact Dez Skinn acted as Davis’s agent in this dispute, penning a letter to Moore and cc:ed to Davis, Leach, Skinn’s American agent Mike Friedrich, and Dean Mullaney in July of 1985, around the time that Miracleman #1 was released in which he bluntly proclaimed that Davis “is withholding his copyrights and refuses to allow the reprinting of the serialised comic strip art known as ‘MARVELMAN Book 2’ by any publisher whatsoever,” and further clarifying that Davis was refusing to allow “any form of subcontracting of his copyright designs to any other artists,” specifically citing Evelyn Cream, the Zarathustra Bunker, Dennis Archer, and Marveldog as designs he was unwilling to let other artists use, and notes that Garry Leach has similarly not approved the use of his designs by other artists. (The letter also cites “lost earnings over the last fiscal year, primarily attributable to the lack of syndication of the CAPTAIN BRITAIN comic strip” as Davis’s reason for refusal, hence its pointedly being addressed to Moore.) yronwode (and presumably Mullaney) were unmoved by this, with yronwode proclaiming shortly thereafter that “Dez Skinn signed a contract with Eclipse allowing us to reprint material from Warrior, and we intend to reprint that material. If Alan Davis granted Dez Skinn the power to make that contract, and has since changed his mind, that is unfortunate for Alan but he is legally bound to that contract. If Dez Skinn represented himself to Eclipse as having the power to represent Alan Davis when in fact he did not, that is a matter for Alan Davis to settle with Dez Skinn. In any event Eclipse will be reprinting the material,” demonstrating Eclipse’s characteristically idiosyncratic understanding of how contracts work.

Skinn, for his part, was already souring rapidly on Eclipse, who had never been the company he wanted to work with anyway. In Skinn’s telling – and note that between Skinn and yronwode this is a story that is long on fabulists – Eclipse immediately became late on payments, and so Skinn began withholding the high quality prints, which Eclipse dealt with by simply making low quality copies from Warrior. (Perversely, Skinn notes, “that made Alan Davis crazy because all the details dropped out.”) Given that Skinn was already (and with good reason) dismayed by the low quality of the first issue, where despite having the high quality artwork they managed to, in the iconic panel of Miracleman proclaiming his return, color his face purple, this was hardly a promising development, and Skinn was surely eager to look for a new publisher that might actually succeed in giving him money.

Eclipse, meanwhile, had moved on to other problems: the material previously published in Warrior ran out midway through Miracleman #6. This posed a problem – as Skinn put it (in the same issue of Speakeasy where yronwode suggested not actually having the rights to Alan Davis’s art was not strictly speaking a problem), “according to our contract, Quality has to supply material to Eclipse up to issue #12.” The problem is that Eclipse’s interest in the new material was predicated on it being written by Alan Moore, who was under no circumstances going to be working with or for Skinn. Skinn, for his part, grumps that this was “something which is not expressly stated in the contract,” but his use of “expressly” highlights the degree to which this is a feeble objection: nobody seriously thought Miracleman (Or, as Moore, dripping with irritation, called him in an essay at the back of Miracleman #2, “M*****man”) was a valuable property except inasmuch as the red-hot writer of Swamp Thing and the forthcoming Watchmen had written for the character. In 1985, at least, Miracleman not written by Alan Moore was essentially worthless.

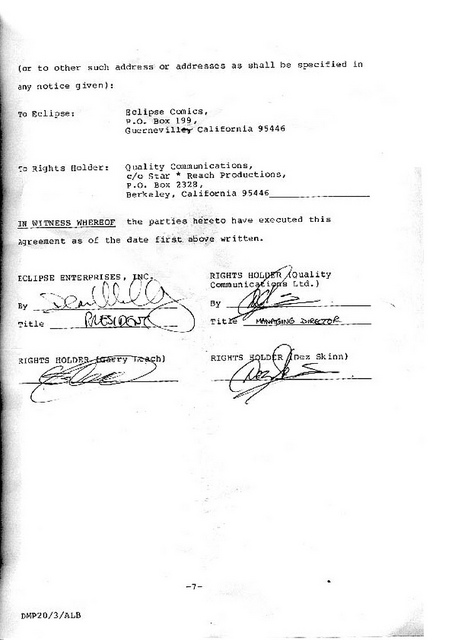

Eclipse’s solution, ratified in a new contract dated February 1986 (the same month that Miracleman #6 is dated), was to buy the right to produce new Miracleman material from Skinn for a further $8000, payable in three installments, one of which Skinn recounts was given to him at a meeting “with Jan Mullaney – Dean’s brother – in New York, in some really seedy bar. He turned up looking like a real hippie with a couple thousand dollars in cash in a brown envelope. And I’m sitting there, this sort of funny Englishman in this really scary place and he comes in and this is like some dodgy transaction taking place as he slides the envelope over to me with a couple thousand dollars or more in cash and he says, ‘you will count it, won’t you?’” This contract also seemingly marks the point where Skinn abandoned his support for Alan Davis’s objections to having his work reprinted, noting simply that “Eclipse also assumes the sole responsibility of payment to and for the creative talent on all issues of Miracleman or any such other titles featuring “Miracleman” and the Characters, including payment of artistic royalties to Alan Moore and Gary Leach representing Alan Davis on the stories reprinted from Warrior Magazine,” and transferring all of the design copyrights Skinn had previously asserted that Davis held to Eclipse.

This is perhaps unsurprising – the fact that Skinn had chosen to direct his letter regarding Davis’s objections to Moore suggests that the position was more about trying to force Moore back into playing ball with Dez Skinn than about concern for Alan Davis. Whereas the entire point of this agreement was to clear the way for Eclipse to hire Moore directly (as opposed to the obviously unworkable plan of having Skinn/Quality employ him). For the purposes of filling out Miracleman #6 and publishing #7, Moore’s involvement was minimal – he’d been ahead in scripting for Warrior, and had three installments written but not drawn. But the problem of getting them drawn was more substantial, since it’s not as though Alan Davis was going to be returning to the gig. Unfortunately, Eclipse’s stable of available artists did not come close to matching that of the major companies. They presented Moore with a few options, and of them he picked an neophyte named Chuck Austen on the grounds, as Austen put it, that he “didn’t draw everybody so that they looked like they were superheroes in street clothes.”

It’s an accurate enough description, but the truth is that Austen’s blocky art style and relatively static faces are a rough transition from the famous fluidity of Alan Davis’s work, especially coming as they do on a page turn from an exquisite splash page of Miracledog (although actually, Austen handles Miracledog pretty well). And the biggest sequence that Austen drew, Miracleman flying into space with Gargunza, kissing him, and then hurling him at the planet in issue #7, is a desperately unsatisfying one. Austen has talked about how he struggled to give the scene the correct emotional content as requested by Moore in his typically detailed script, saying how “you want Gargunza to look dazed and totally lost and realizing that it’s all over and there ain’t shit that he can do about it. And at the same time you want this almost tender, totally controlling happening in the panel where Miracleman looks like he’s absolutely in control and Gargunza is resigned to the fact. That’s the hardest part to me, and the part that’s also fun. That energizes me, working on that emotional level trying to get the character to express that inner thing that’s going on.” Which is all well and good, although Moore’s captions, which clarify that Gargunza, in the vacuum of space, is “barely conscious” rather cuts against them, but there’s simply no way to avoid the fact that Austen’s static and slightly cartoonish art ends up looking more like Miracleman is throwing a mannequin at the planet. Still, after eighteen months, the cliffhanger was resolved, and audiences at last found out how a depowered Mike Moran escaped the jaws of the mutant canine formerly known as Marveldog.

At this point, however, things really started to go wrong. Some of this was entirely understandable; in February of 1986 heavy rainfall flooded the Russian River, resulting in a fifty foot flood through Guerneville California, where Eclipse was headquartered. Unsurprisingly, this resulted in delays, with Miracleman #8 being published as a set of Mick Anglo reprints with a Chuck Austen-illustrated framing sequence in which cat yronwode explained the situation while decrying the usual practices of desperate comics publishers where they try to shoehorn reprints into the ongoing narrative. The only direct effect of this was the month delay to Miracleman #9, but it did considerable damage to Eclipse’s finances, exacerbating almost all of the existing issues with the company.

This was also roughly the point where Eclipse lost the services of Chuck Austen after yronwode called Austen at home and screamed down the line at his grandmother because some pages were late, resulting in Austen refusing to work for Eclipse anymore. That meant finding a new artist. But Eclipse very nearly faced an even bigger problem when yronwode attempted the same basic approach with Moore himself, calling him to demand the scripts for forthcoming issues, which Moore had not yet started work on because he was waiting for the issue with Alan Davis’s rights to be settled. As Moore recounts it, “she was being very blustery, and trying to make out that I’d done something wrong, while not answering my questions about this paperwork. She said something else that sounded offensive and I said, ‘Well, perhaps we could just stop the entire project right here,’” resulting in Dean Mullaney, who had apparently been listening in on the call, cutting in to promise that the paperwork was forthcoming, but asking if Moore would start work while waiting for it, which Moore agreed to.

(Moore apparently forgot about the paperwork after this point, or at least did not pursue it further, since, as Davis points out, no such paperwork existed and Eclipse’s reprints of his material were entirely unauthorized. Davis, for his part, is absolutely withering about this anecdote, noting that he “felt really sad that Alan’s work had been so badly impaired by deep concern over the legality of Eclipse publishing MY art. He was so distraught in fact, that he must have forgotten he had my address and telephone number, or if he was too nervous to call, could have contacted me via a mutual acquaintance like Jaime Delano.”)

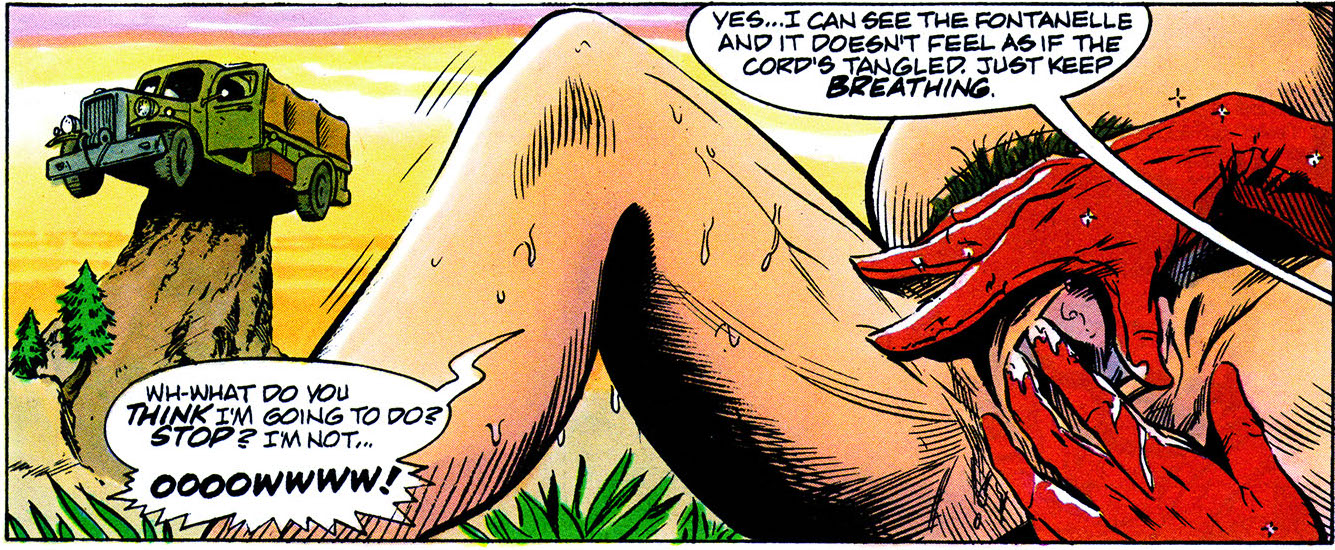

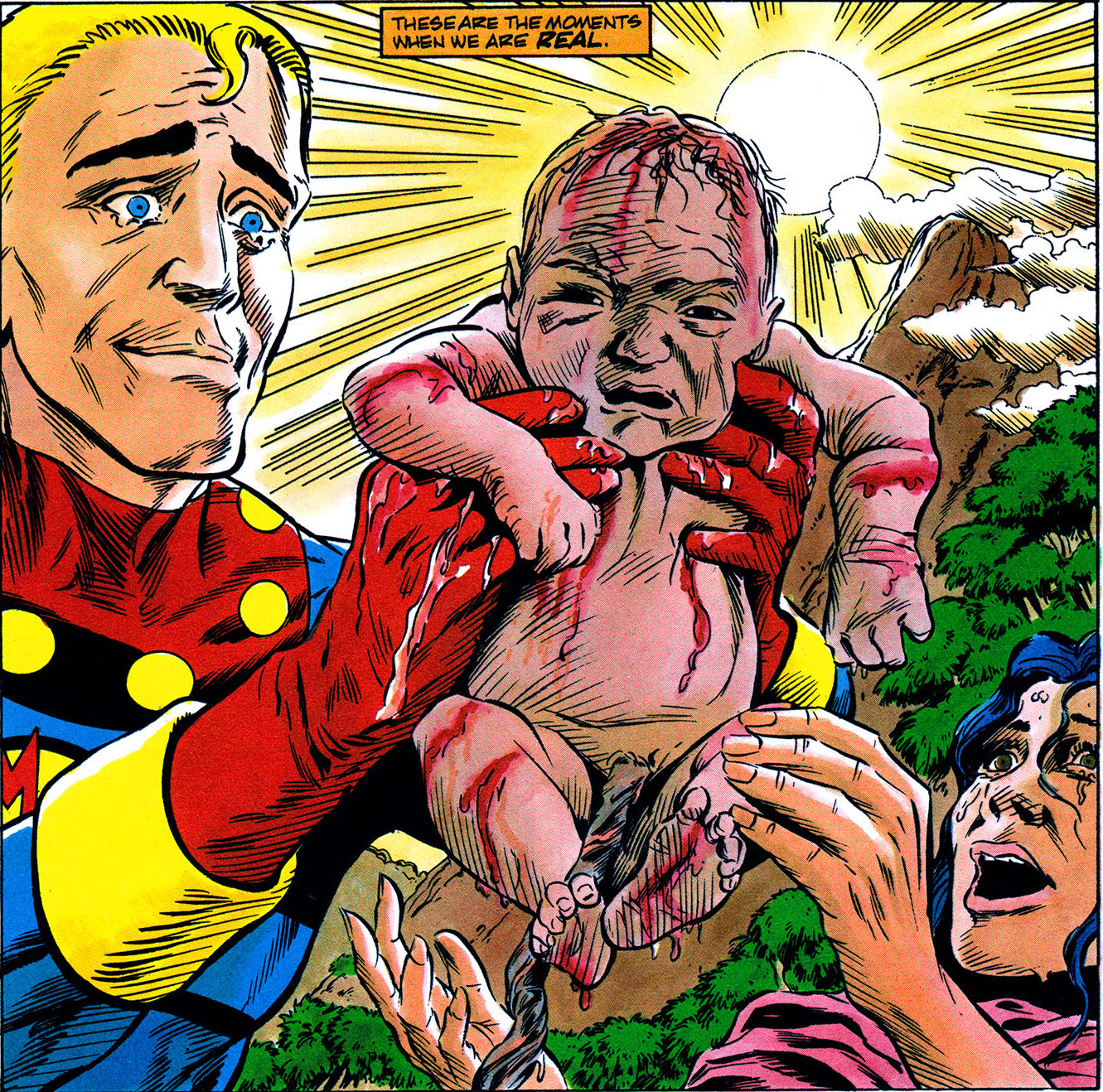

With Moore mollified, work could begin on what would end up being one of the most famous issues of Miracleman, and indeed of Moore’s career – one that would, indirectly, lead to the fracturing of his relationship with his other major American publisher, DC Comics: “Scenes From the Nativity.” On art chores for it was Moore’s frequent Swamp Thing collaborator Rick Veitch (explaining, perhaps, why John Totleben stepped in to do the conclusion of the “Greening of Gotham” arc at around the same time). And what a job Moore gave him; the issue featured, as the warning label on the cover put it, “graphic scenes of childbirth,” which is to say five detailed panels over the course of the issue of Liz and Miracleman’s child emerging from the birth canal. The story had been one Moore had been planning for some time; Moore recalls a conversation with Dez Skinn in the latter days of Warrior where he noted that, with Liz pregnant, they were going to have to tackle the birth of her child at some point. “I suppose it depends what kind of angle you take upon it,” Skinn replied, to which Moore said, “well, how about from the front?”

This is difficult to quite believe, at least as a sincere suggestion to Skinn who, by that point, had already had a small freakout over Moore’s use of the word “period” in an earlier installment, although given how fraught Moore and Skinn’s relationship was by the end of the comic’s Warrior run it’s certainly possible that Moore was simply seeking to wind him up as opposed to making a proposal he actually thought was likely to make it into the comic. But either way, now that he was free of Skinn and clearly at a publisher that needed him more than he needed them he decided to go with it. This was, by all appearances, the plan from the start of the Eclipse iteration of the story – Austen recalls talking to yronwode about the forthcoming issue, saying that she “was not really happy about the idea. ‘You’re taking a super-hero book and you’re putting a birth scene in the middle of it.’” yronwode, for her part, vigorously disagrees with this account, noting that Eclipse had previously published Sabre, which had a depiction of childbirth “although after the art was drawn, a word balloon was put over the woman’s vagina and it was covered up,” and that an earlier issue “was, as far as I know, the first American four-color comic that showed a girl getting her first menstrual period.” In her telling, she firmly “didn’t think there was going to be any problem,” and indeed claimed to have obtained the photo reference used by Veitch by photocopying pages of Lennart Nilsson’s A Child is Born, saying that “if you compare the book – which is available in almost every public library – with the pictures in Miracleman you’ll see that they are copies from that,” presumably assuming nobody would bother to do so, as it’s not even remotely true.

For Moore’s part, the point was straightforward. “I’ve seen some birth scenes in comics where it seems that the artist has probably taken the woman’s poses from a porn magazine. Just change the expression on the faces slightly and everything was posed so that you can’t actually see the genital area. And it struck me, having seen a couple of childbirths m’self – I mean, I find them quite magnificent. Stunning. Both occasions were stunning occasions; it was an incredible kinda powerful moment. I thought, well, this was something sacred I’m talking about. I really shouldn’t have to be bothered with the self-imposed problems and laws or whatever of the American comics industry.” And indeed, the issue fits smoothly into the larger pattern of Moore challenging the censorship of the American comics industry, first with getting DC to publish Swamp Thing without the approval of the Comics Code, then subsequently in his decision to do issues about menstruation and psychedelic vegetable sex. And, of course, it was Miracleman #9 that provoked Steve Geppi into launching a moral crusade to clean up comics, resulting in DC’s proposed ratings system and Moore’s schism with the company.

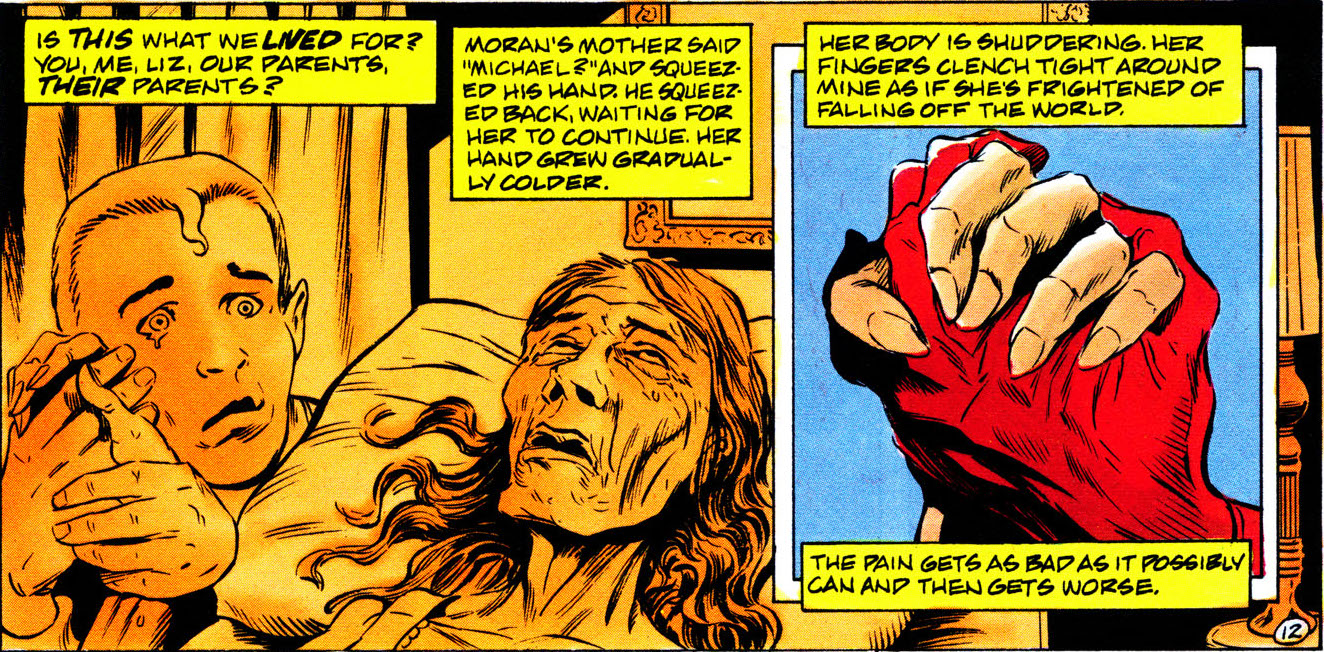

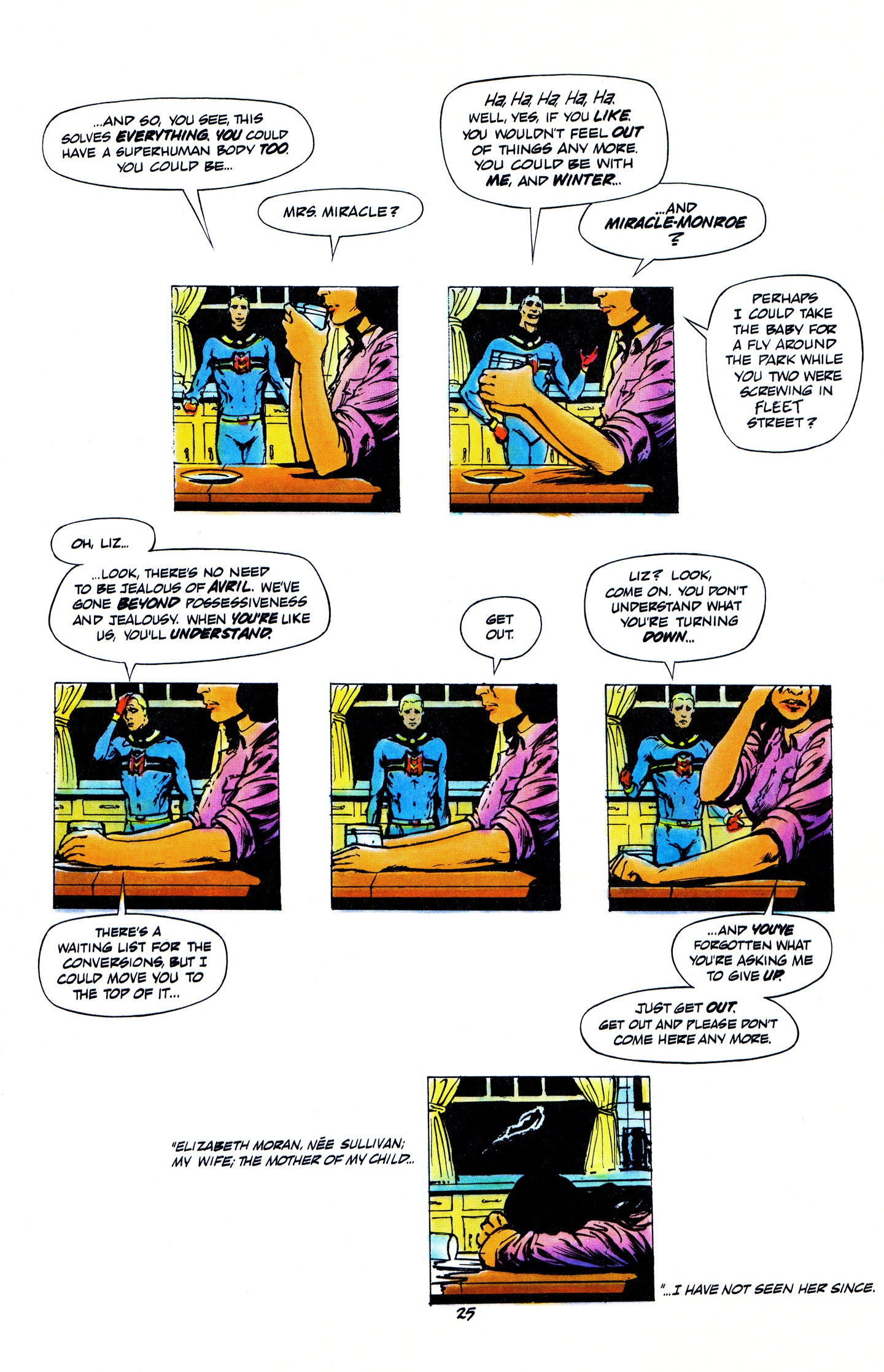

While the five panels explicitly depicting Liz Moran’s dilated vagina caused the lion’s share of reaction to Miracleman #9, they were far from the whole of the issue. Miracleman #9 marks the first time Moore wrote an installment of Miracleman as a single issue, although notably he still structures it as two short scenes (an eight-pager and a six-pager) separated by a two page interlude focusing on Johnny Bates. The first section deals fairly straightforwardly with Miracleman and Liz’s reunion and exit from the Zarathustra complex, depicting it straightforwardly and without captions. The second section, on the other hand – the one actually depicting the birth – runs alongside narration from Miracleman addressed at the late Emil Gargunza, with full color panels of Liz giving birth juxtaposed with sepia-toned flashbacks of major events in the character’s mythos. So, for instance, as Miracleman asks “is this what we lived for? You, me, Liz, our parents, their parents? Moran’s mother said ‘Michael?’ and squeezed his hand. He squeezed back, waiting for her to continue. Her hand grew gradually colder. Her body is shuddering. Her fingers clench tight around mine as if she’s frightened of falling off the world. The pain gets as bad as it possibly can and then gets worse,” the art first features a young Michael Moran crying by his mother’s deathbed, and then, with the switch to “her body is shuddering,” a close-up of Liz and Miracleman’s hands entwined.

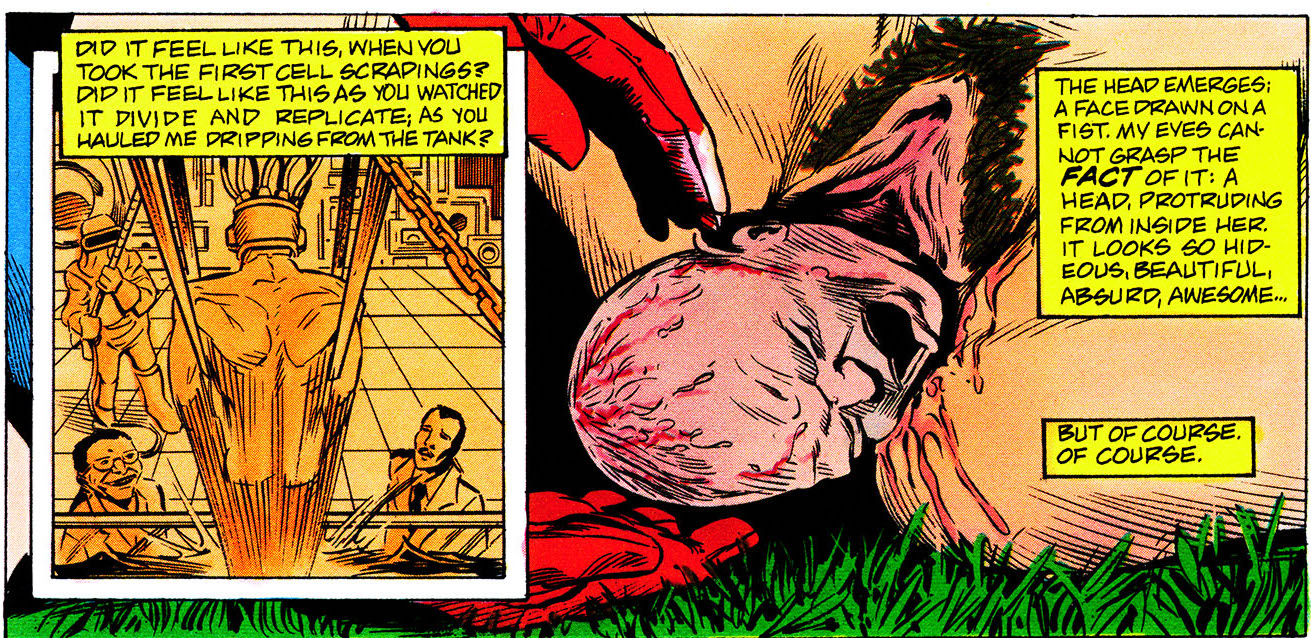

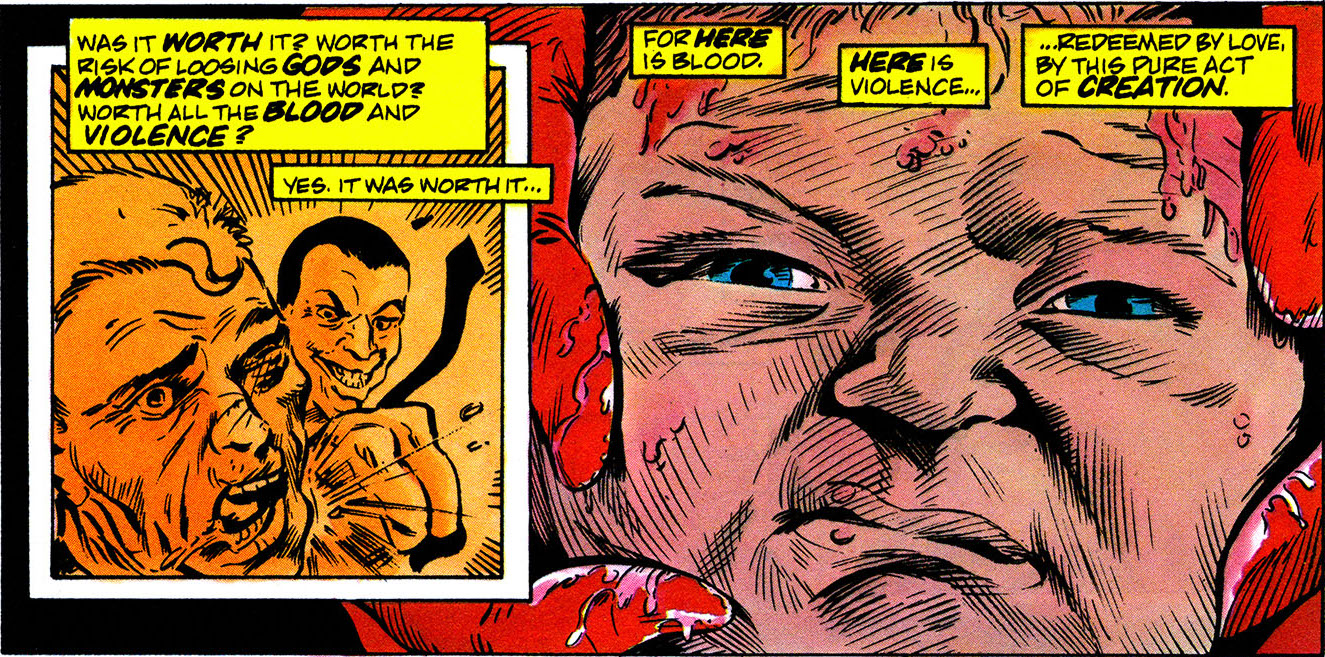

As the sequence reaches its most famous page, it switches structure, the sepia-toned panels becoming insets on the full-color ones instead of the other way around as the baby’s head emerges. “Did it feel like this, when you took the first cell scrapings,” Miracleman asks the absent Gargunza. “Did it feel like this as you watched it divide and replicate; as you hauled me dripping from the tank? The head emerges; a face drawn on a fist. My eyes cannot grasp the fact of it: a head protruding from inside her. It looks so hideous, beautiful, absurd, awesome. But of course. Of course.” And finally, as Miracleman grasps his daughter’s head to finish delivering her, he asks, “was it worth it? Worth the risk of loosing gods and monsters on the world? Worth all the blood and violence?

It is, of course, a standard technique for Moore, right down to the heavily iambic flow of the narration. But the content is remarkable. It’s not that Moore hasn’t blended imagery of sex and death before, most obviously in “Rite of Spring,” where the orgasmic unity of all things includes a description of how “my enemy’s blood erupts to fill my mouth with molten copper,” but notes that “there is no contradiction” between this and sexual passion. Or, for that matter, in the description of the “almost sexual hatred” between Miracleman and Kid Miracleman in their early confrontation. But, of course, “Scenes from the Nativity” is not about sex, even though it contains the most detailed depiction of female genitalia to grace Moore’s work prior to Lost Girls. “Rite of Spring” stretched the definition of sex to its widest point, but stayed firmly within the realm of the erotic; “Scenes from the Nativity,” on the other hand, retains all the sense of taboo and sacredness, but strips it down to the most elemental binary, proclaiming that “in the careless and foggy continuum of our lives, these precious moments burn like suns: birth, death… these are the moments when we are real,” the final phrase coinciding with a 2/3 page panel of Miracleman and Liz crying as they hold the just-delivered Winter up to the gleaming sun. And in turn all of this is presented as the true and inevitable teleology of superheroes, with all of the ornately rewritten mythology of Miracleman being framed explicitly as something existing only to lead to this moment. It is, in short, a tour de force.

Veitch stayed for one further issue, rounding out Book Two of Miracleman (which had begun back in Warrior #13) with a story alternating between showing Mike and Liz’s new domestic life with their slightly unsettling new child and two mysterious figures speaking a strange alien language looking for the “cuckoos,” who are clearly the subjects of Gargunza’s experiements (including a previously unseen woman who flees before they can find her, marking the introduction of Miraclewoman). But whereas first nine issues had come out more or less monthly, with no more than a two month gap between them, Miracleman #10 came out in December of 1986, five months after “Scenes from the Nativity.” Gaps of this size would remain the norm for the remainder of Moore’s run on the title, as well as for Neil Gaiman’s follow-up, with more than a year separating Moore’s last two issues.

Part of the reason for these delays was that the artist on the final six-issue stretch of Moore’s run, John Totleben (who, like Veitch, came over from Moore’s Swamp Thing work), was diagnosed with a degenerative eye condition shortly before he began work on the series, which slowed his work considerably. But given that the scheduling difficulties continued even after Gaiman and Buckingham took over the title, it is difficult not to assume that Gaiman’s explanation of the delays applied to his predecessors as well. As Gaiman puts it, “the bit nobody ever knew was that we wouldn’t start writing until we got paid for the last episode. I would stop writing and Mark wouldn’t start drawing. It wasn’t that we were a year late. It was like one day our checks would turn up and then we start working on it because the checks were so amazingly unpredictable from these guys. We didn’t realize at the time that they were being creative with the royalties, all the stuff that wound up[ sending them into bankruptcy.”

Adding to the frustration for readers was the rapidly increasing price of the issues. When the Eclipse series had launched in 1985 it had been priced at ¢75, the industry standard price shared by Swamp Thing. With issue #5 it jumped to ¢95, a modest increase, especially given that as of issue #9 the actual Miracleman material was reduced to a mere sixteen pages per issue, with a Laser Eraser & Pressbutton strip usually making up the rest of the issue. But with the start of the John Totleben issues the price jumped again to $1.25, and, two issues later, to $1.75. Both of these increases coincided with larger jumps in the industry, but it was difficult not to feel that $1.75 was rather a lot to spend for Miracleman #13, which didn’t even feature new material in its backup strips, instead reprinting a pair of Mick Anglo stories on top of its meager sixteen pages of new content. (Although the all-time record for appalling pricing is held by Marvel’s 2014 reprint of issue #14, which cost $4.99, padded the sixteen page story out with reproductions of Totleben’s pencilled art, some figure studies, and a Mick Anglo reprint, and managed to misprint the issue so that one of its most famous scenes lacked any dialogue, then declined to offer a reprint.)

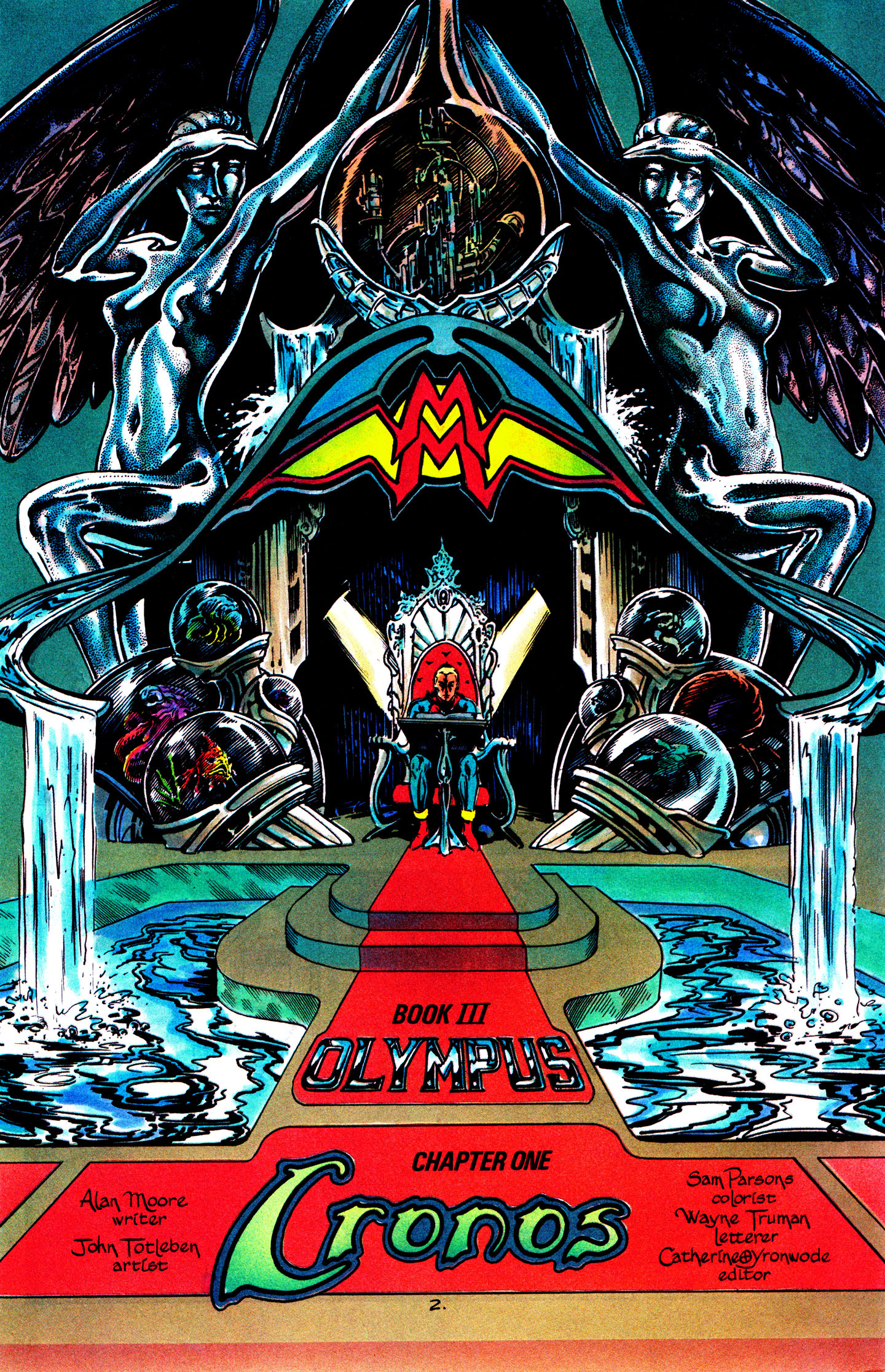

Given all of this, it’s hardly surprising that when Moore called Neil Gaiman around the time of Miracleman #10’s publication to offer him the opportunity to continue the series Moore described it as a “poisoned chalice.” But in some ways his more interesting warning came after Gaiman expressed interest when, in Gaiman’s telling, he said “now I should warn you by the end of Miracleman #16 I will have solved all crimes, ended all war, and created an absolutely perfect world in which no further stories can occur. Do you want to back out now? Please feel free.” Indeed, although the means by which this happens are not fully revealed until Moore’s final issue, this radical state of affairs is introduced at the start of Miracleman #11, which jumps five years forward from the 1982 setting of the main story to 1987. This is a sly move on Moore’s part; 1982, of course, had been the present day when the series debuted in Warrior, and the five year time jump brought it to the present day. But whereas “A Dream of Flying” took place in a 1982 that was, at first glance, the same as one it was published into, “Cronos,” the first part of Book III, also titled Olympus, opens with Miracleman in a vast palace of crystal inscribing “tales of how it feels to live in a mythology” into a book made of steel while sitting upon a throne adorned with beautiful metal statues and strange alien flora and fauna. All but three of the sixteen pages consist of his tales, a flashback to 1982 that picks up where Miracleman #10 left off, but over the course of those three pages it becomes increasingly clear that Miracleman is in fact ruling the entire planet. Instead of starting from the world of the reader and slowly twisting it into something new, Moore was now presenting a world that was radically unlike that of the present day, even as he asserted that it took place there, twisting the premise so that it began from the alien instead of from the human.

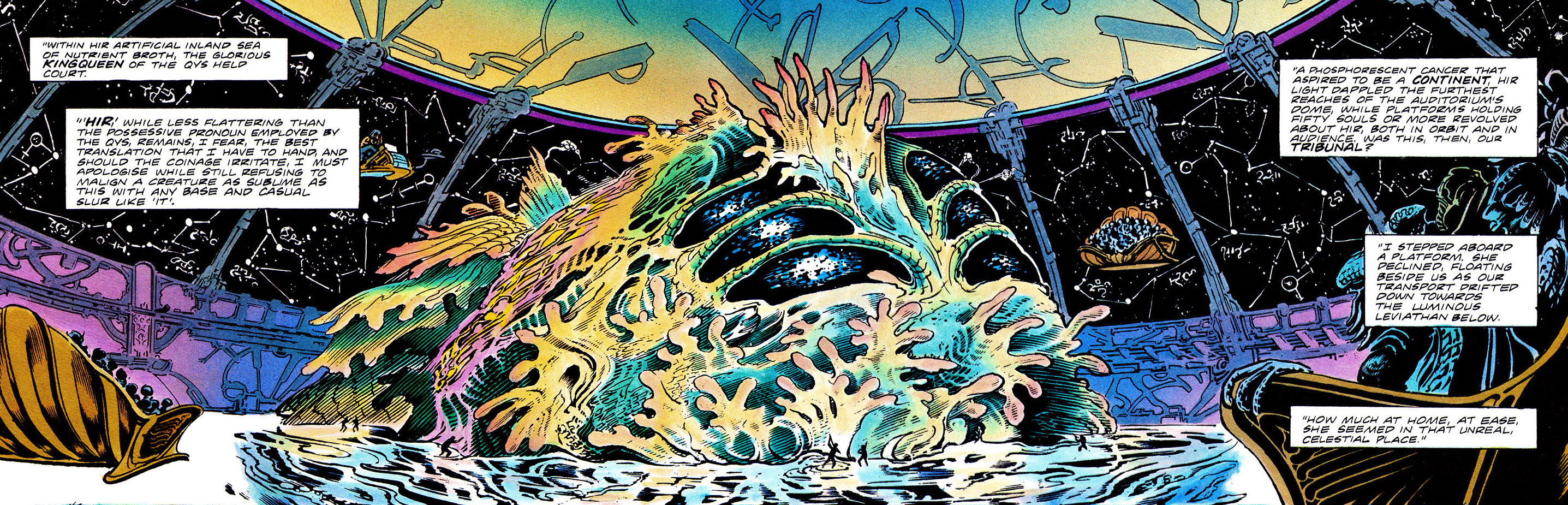

This is reflected throughout the Olympus arc, which uses the 1987 frame story for each of its first four installments. But more broadly, it is reflected in the focus of the arc, which moves from untangling Moore’s reimagining of Mick Anglo’s original mythology to exploring the worlds of the alien races that Moore established as the true origins of the character. In some ways this is a mixed bag; the space-bending Warpsmiths and body-swapping Qys are interesting concepts, and Totleben’s depiction of them, heavily indebted to classic pulp illustrator Virgil Finlay, is at once lush and unsettling, living up to Moore’s description of “a phosphorescent cancer that aspired to be a continent, hir light dappled the furthest reaches of the auditorium’s dome, while platforms holding fifty souls or more revolved around hir, both in orbit and in audience,” as he has Miracleman describe the Kingqueen of the Qys. But with as many other plot threads as Moore is juggling through the four sixteen-page installments leading up to his denouement, their development is scant, and they never really progress beyond being interesting ideas, a tendency exemplified when a discussion of whether the Warpsmiths and Qys are necessarily locked into an endless cycle of war is resolved by Miraclewoman casually suggesting “couldn’t you have sex instead” and explaining that “if two organisms or two cultures are forced into contact it can be thanatic and destructive, or erotic and creative,” an observation that basically fixes everything.

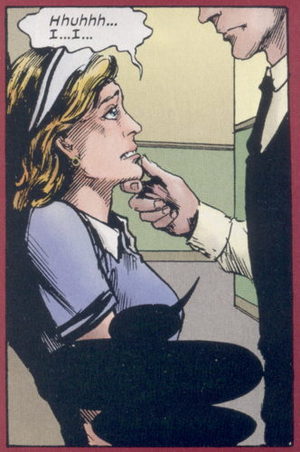

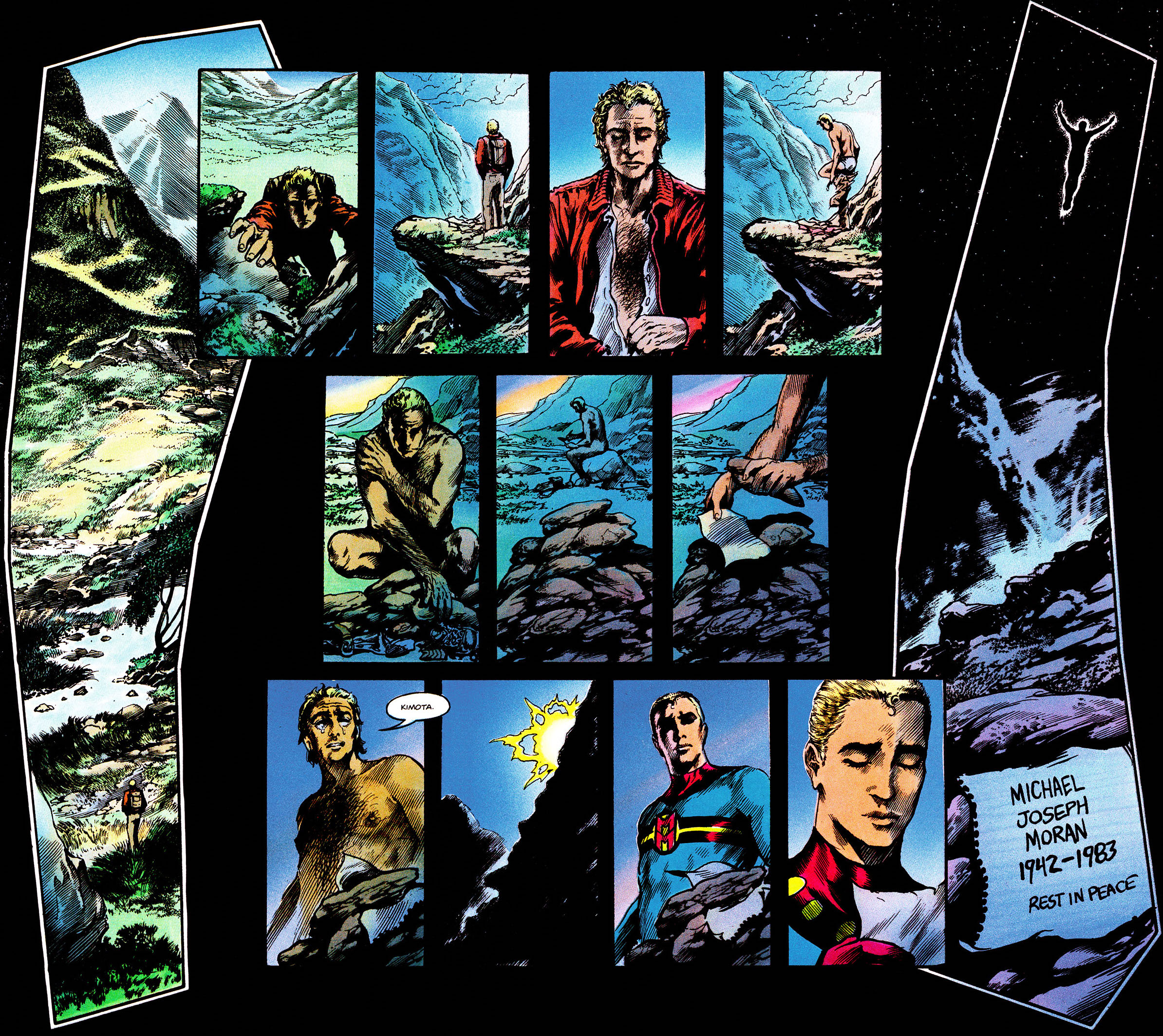

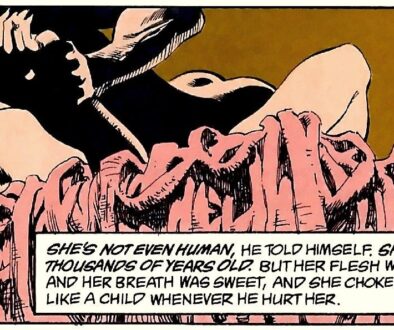

That is not to say there are not impressive moments in these issues, most obviously a two-page sequence in Miracleman #14 in which Mike Moran travels to Scotland, climbs a mountain, strips, buries his clothes beneath a small cairn, and then places a scrap of paper atop it before saying his magic word for the last time. Miracleman picks up the scrap of paper and reads it before flying away, with the final panel revealing its contents to the reader: “Michael Joseph Moran 1942-1983.” And the stories of behind-the-scenes drama pile up as well, most notably a panel in issue #12 in which Young Nastyman commits necrophilia, a moment that’s relatively subtle in the issue itself, but that in the script was, as Totleben fondly recalls, “a real howl. It was incredibly graphic and excessively lurid. I think maybe he was going a bit over the top just to antagonize them or something,” leading to a lengthy conference call with Totleben over it in which he shocked Dean Mullaney by declaring that he was not particularly bothered by drawing the panel, pointing out that Moore had called for a very large panel of Miraclewoman in classic William Moulton Marston-style bondage and that very little of Moore’s detail would actually be able to make it into the panel.

But for the most part these four issues are mere preludes to Miracleman #15, which rivals issue #9 in terms of its impact and infamy for reasons that are at once similar and radically different. The issue deals with the return of Kid Miracleman, who finally escaped the prison of Johnny Bates’s mind at the end of the previous issue when Bates was sexually assaulted by other children at the hospital and tearfully and desperately used his word. (This results in the iconic scene in issue #14 that Marvel subsequently misprinted the dialogue of in which Kid Miracleman informs a nurse, “you were the only one who was kind to me” and declares that he’ll let her live, walking off, then doubling back and saying, “I’m sorry. They’d say I was going soft, wouldn’t they” and vaporizing her skull, a scene notably ripped off almost note for note a quarter-century later by television writer Toby Whithouse in Being Human.) It is an interesting question exactly when Moore decided on this resolution and its consequential establishment of a utopian society under Miracleman’s authority. His original outline pitching his ideas to Dez Skinn had left off with the Gargunza storyline that made up Book Two and a vague description of “an encounter with the alien race whose starship fell to Earth in Wiltshire all those decades ago.” But he clearly had some idea along these lines by the time of 1982’s Warrior #4, for which he penned “The Yesterday Gambit,” which presented itself as a flash forward in Miracleman’s timeline and included the Warpsmiths, the return of Kid Miracleman, and Miracleman’s underwater fortress Silence, all of which feature in Miracleman #15, although in forms that are not entirely compatible with “The Yesterday Gambit,” which was the one Marveleman story from Warrior that Eclipse declined to reprint. (Despite this, Moore references its events directly in issue #15, positioning them as one of the many apocryphal legends of the fight, “each with its own adherents; as valid, if not more so, as the truth.”)

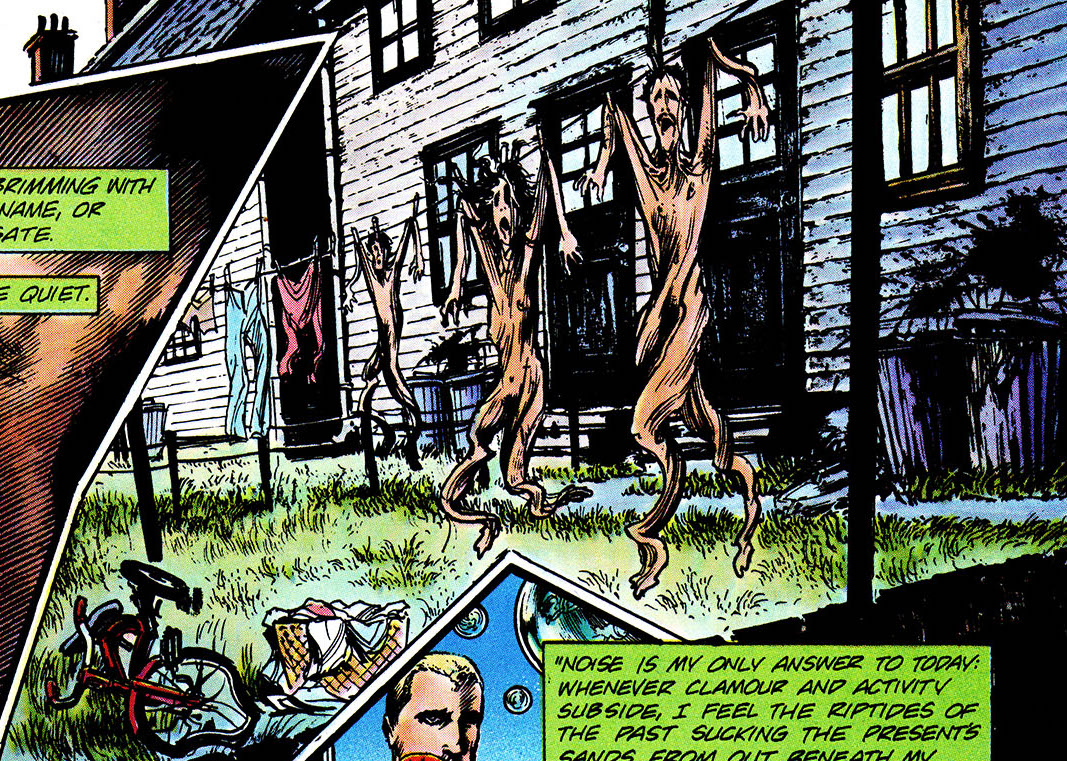

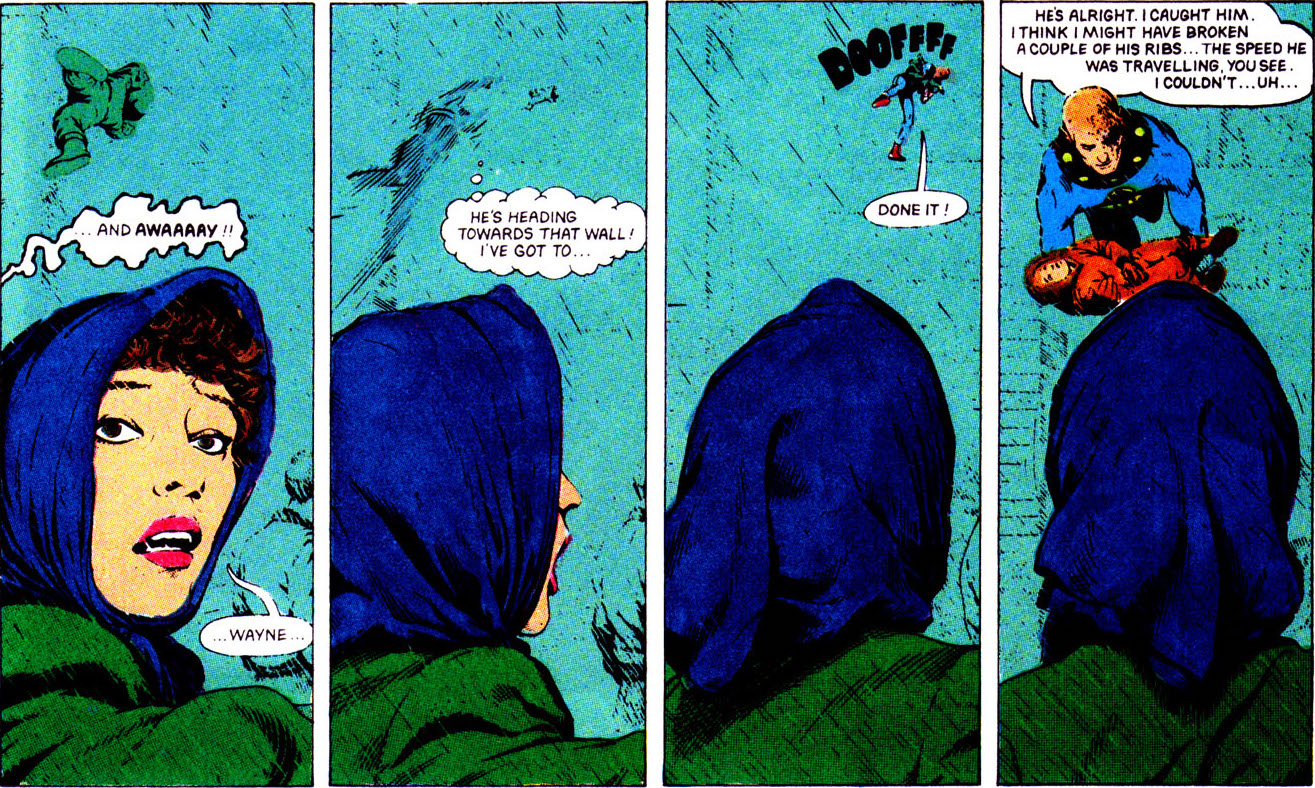

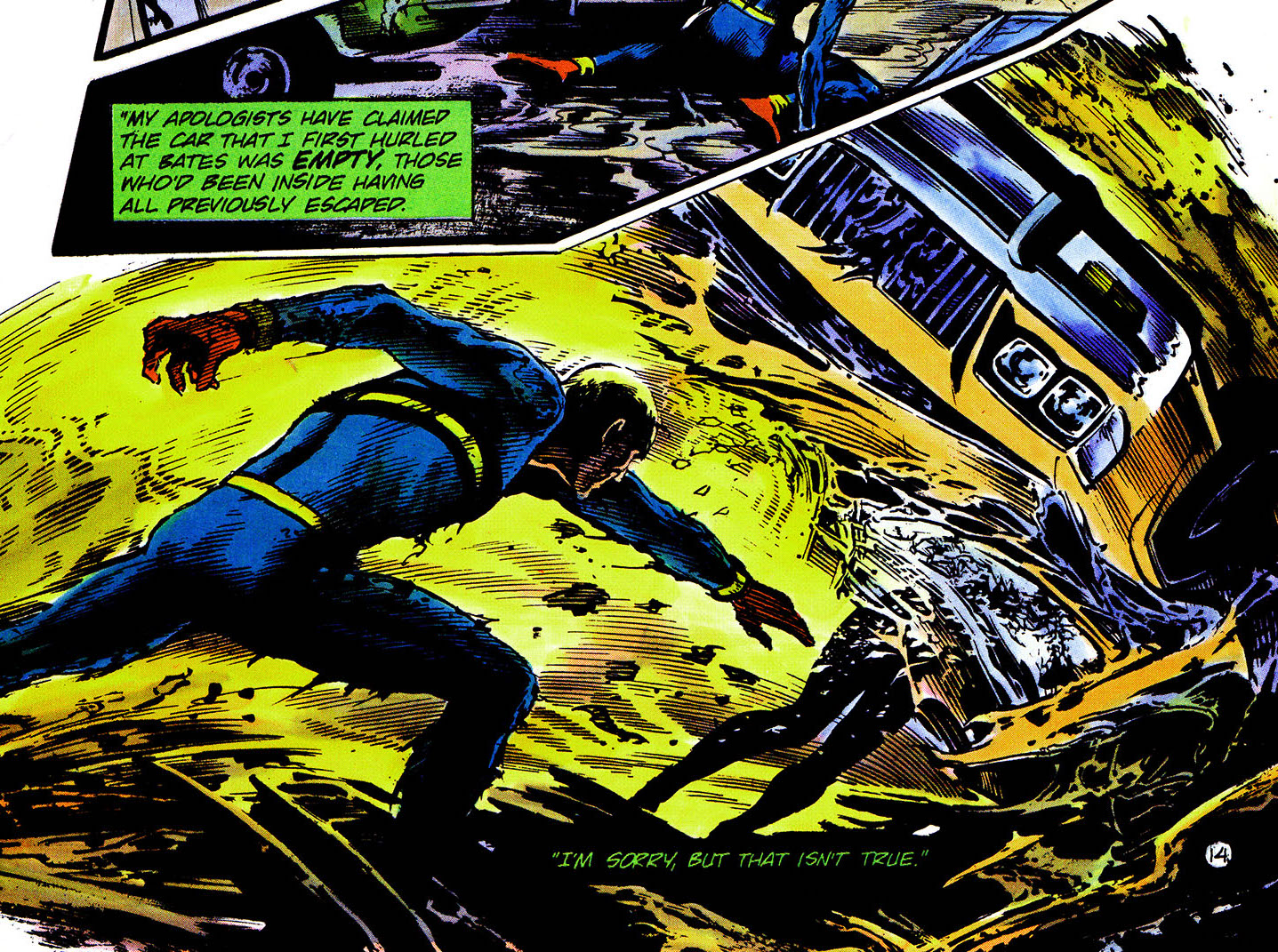

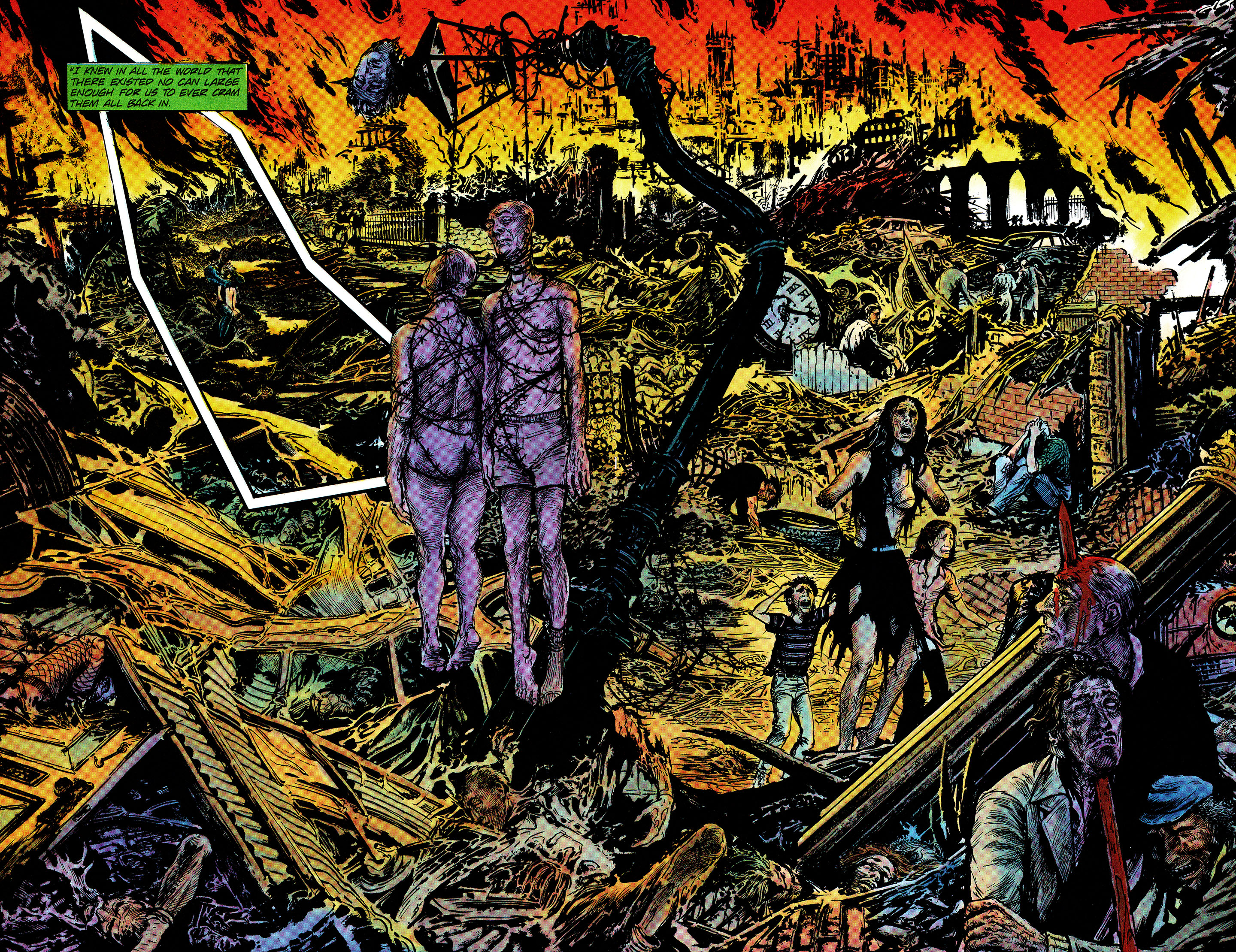

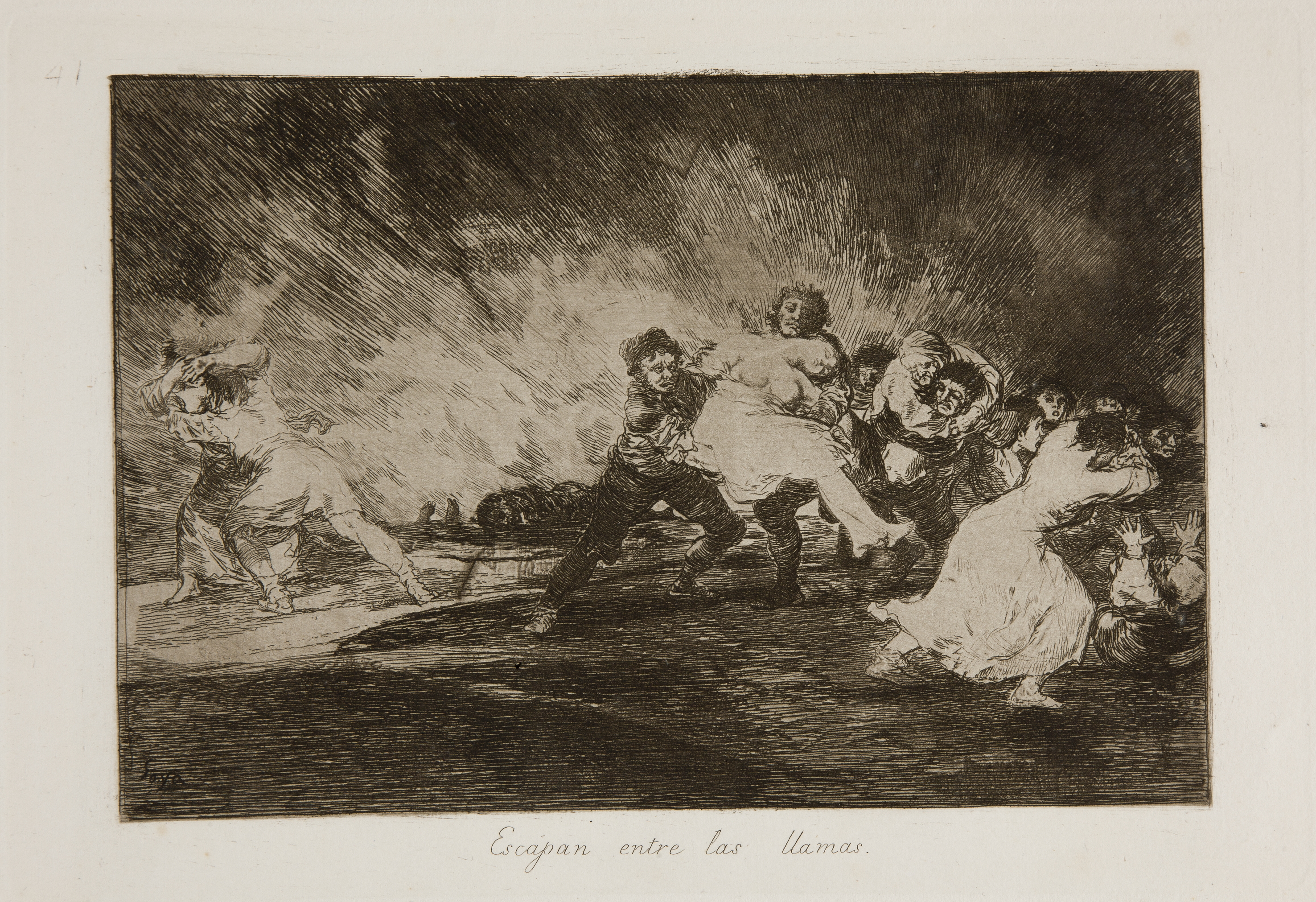

But nothing in “The Yesterday Gambit” hints at the shocking brutality of Miracleman #15. Moore’s explanation for the issue was wanting to “show a superhero fight as it really might be. Let’s just show how bad it might really get if you had Superman and Bizarro punching out in downtown Metropolis.” Moore had grappled with some of this in the first Miracleman/Kid Miracleman fight when, for instance, Kid Miracleman hurls a baby through the air in the middle of the fight, distracting Miracleman by throwing a baby at a nearby building, which Miracleman of course saves, but with the note that he’s broken a couple of the baby’s ribs because of the speed he was traveling, a grimly funny note of realism in a standard superhero trope. There’s a not entirely dissimilar moment in Miracleman #15 when Miracleman, in another fairly standard superhero punch-up moment, picks up a car and throws it at Kid Miracleman. “My apologists have claimed the car that I first hurled at Bates was empty, those who’d been inside having all previously escaped,” he narrates. “I’m sorry, but that isn’t true,” the final caption box changing color to be yellow on black – Bates’s colors. The shift in tone – from a winking subversion of the “superheroes save everybody” to a stark-faced refusal to offer any sort of salvation at all – is stunning.

And this is hardly the only such moment in Miracleman #15, an issue that returns over and over again to images of stark brutality. Kid Miracleman, under Moore, had always been portrayed as a brutally sadistic figure, whether in his mocking murder of his secretary in his first appearance “just to show you that I don’t mind doing that sort of thing. In fact, I quite enjoy it” or in his dispatching of the nurse in Miracleman #14. But what is striking – especially for Moore – is that the issue contains almost no textual descriptions of what Kid Miracleman does to London. Early on the narration establishes that Bates spends hours in London before Miracleman and company realize he’s back, and talks about “those hours that he had crammed with centuries of human suffering; those narrow side-streets filled with miles of pain. Having exhausted all the humdrum cruelties known to man quite early in the afternoon he had progressed to innovations unmistakably his own,” and the end narration makes a fleeting and bleak mention of “coral reefs of baby skulls, and worse,” but this is the extent to which Moore uses the written word to frame these depravities into the sort of classic and endlessly quotable lines that had characterized, for instance, Rorschach’s famously bleak narration in Watchmen. There are neither “abattoirs of retarded children” nor “gutters full of blood” to drown the vermin in.