Chapter Eleven: By Another Mans (Look Upon My Works Ye Mighty)

And so at last the story returns to where it began. Grant Morrison has, of course, been ever-present. As already discussed at length, his first professional credit predated Moore by five months. But he has been a shadow presence in the narrative, lurking at the edges, occasionally contriving to intersect it, waiting for his moment to take the stage in earnest. And now at last he arrives having always been here, and it becomes necessary to trace the story backwards, figuring out who he has been all this time.

And so at last the story returns to where it began. Grant Morrison has, of course, been ever-present. As already discussed at length, his first professional credit predated Moore by five months. But he has been a shadow presence in the narrative, lurking at the edges, occasionally contriving to intersect it, waiting for his moment to take the stage in earnest. And now at last he arrives having always been here, and it becomes necessary to trace the story backwards, figuring out who he has been all this time.

This is, of course, a strange moment in which to observe Morrison, as he remains resolutely unspectacular. The work through which he will define himself is still ahead, the earliest plausible instances of it not emerging until two months after Watchmen finishes, his American debut still almost a full year away. At this point his greatest accomplishment is Zoids, where he surely acquitted himself well, but where he no more established himself as an impending major talent than Alan Moore established himself as the man about to revolutionize comics with Skizz or Captain Britain. His career at this point has no V for Vendetta or Marvelman, nor even a Ballad of Halo Jones. To read the future out of this moment is to work in implication, finding patterns in the negative space. Getting it right is more about knowing the answer ahead of time than insight.

As a result, it is easy to overreach—to confuse historical event and inevitability. On a very basic level, whatever larger conclusions and patterns are inferred, the answer to how Grant Morrison achieved what he did and how he took up his role in the War is simple: he put a lot of work into writing comics that changed the world. This work did not exist in a vacuum; plenty of extremely talented people have worked just has hard to have an insignificant fraction of the insight. Nevertheless, to treat Morrison’s career as some historically deterministic phenomenon that extended out of Alan Moore’s actions would be an egregious error.

As a result, it is easy to overreach—to confuse historical event and inevitability. On a very basic level, whatever larger conclusions and patterns are inferred, the answer to how Grant Morrison achieved what he did and how he took up his role in the War is simple: he put a lot of work into writing comics that changed the world. This work did not exist in a vacuum; plenty of extremely talented people have worked just has hard to have an insignificant fraction of the insight. Nevertheless, to treat Morrison’s career as some historically deterministic phenomenon that extended out of Alan Moore’s actions would be an egregious error.

So too would it be to suggest, as Morrison repeatedly does, that his career could have happened without Moore. Did Morrison come to writing comics on his own? Yes. Did he have his own interests and influences that, while certainly overlapping with Moore, were nevertheless his, interpreted and responded in ways utterly and necessarily unique to him? Yes. But none of that changes the fact that the career Grant Morrison had existed in a large part because Alan Moore did it first. The wave of Karen Berger edited books that started with Animal Man happened because Alan Moore did Swamp Thing. The genre of literate, politically invested superhero comics for adults that Morrison made his name in originated with Marvelman and V for Vendetta. Morrison admits as much, both in 1985 when he acknowledges that “only the advent of Warrior convinced me that writing comics was a worthwhile occupation for a young man” and much later in Supergods when he describes how he and the rest of his generation hit the American superhero scene in the wake of Moore: “And so we arrived in our teens and twenties, in our leather jackets and Chelsea boots, with our crepesoled brothel creepers and skinhead Ben Shermans, metal tattoos, and infected piercings. We brought to bear on the ongoing American superhero discourse the invigorating influence of alternative lifestyles, punk rock, fringe theater, and tight black jeans. We rolled up in anarchist hordes, in rowdy busloads, drinking the bars dry, munching our hosts’ buttocks (artist Glenn Fabry drunkenly assaulted editor Karen Berger’s glutes with his molars), and swearing in a dozen or more baffling regional accents. The Americans expected us to be brilliant punks and, eager to please our masters, we sensitive, artistic boys did our best to live up to our hype.”

The truth is that it was never Moore’s work that Morrison was imitating, but his career. There are similarities in their works, yes, but the truth is that there are even more similarities between Moore’s work and that of Neil Gaiman, whose early DC comics are much more faithful in their imitations of Swamp Thing than Morrison’s. So why is Gaiman the acknowledged protege and Morrison the despised rival? Again, one answer to this question extends out of specific decisions and choices—specific actions Morrison took in crafting his public persona that alienated Moore, and specific decisions both men made in the face of that antipathy. Another answer, however, is more esoteric, extending less out of decisions anybody made than out of the fundamental cultural relationships in play—a necessary consequence of the particular streams of influence and iconography that both men brought to the precise historical moment they did.

In this regard, contributing factors. First of all, Morrison was always more straightforwardly rooted in superheroes and genre fiction than Moore. He writes of this love with vivid and tangible passion throughout Supergods, making it clear that superheroes were not merely a genre he enjoyed, but something deep and central to who he was in a way that none of Moore’s comments on childhood love of the genre ever suggested. For Morrison, superheroes were an object of almost religious importance, the “Faster, Stronger, Better Idea” that could fight “the Idea of the Bomb that ravaged my dreams.” As he puts it bluntly in Talking With Gods, during a period in which he didn’t go out or do anything, “I really felt like they’d saved my life in a way.” Even his wider interests tended to circle back to this—a 1977 article for the fantasy fanzine White Tree, to which Morrison also contributed the an ongoing serial entitled Armageddon and Red Wine, tackled the genre of sword and sorcery literature through the lens of Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian comics. And indeed, the fact that his 1970s zine work was on fantasy in the general case, in contrast with, say, Alan Moore, who was bouncing around the Northampton Arts Lab dabbling in a broader spectrum of avant garde and performance art.

Even when Morrison, in his account, fell out of love with superhero comics for a couple of years following his disappointment at the 1978 Superman vs. Muhammad Ali (a period, notably, that overlapped precisely with Captain Clyde), his interests stayed broadly in the sci-fi/fantasy niche. Where Moore had roots in the avant garde and the underground comix scene as well, Morrison had more of a singular tap root into the sci-fi/fantasy genre in general, and superheroes in particular. This is not to suggest that Morrison’s roots were comparatively impoverished, although Moore would surely draw that conclusion, nor that Moore’s roots did not also contain deep affection for and knowledge of superheroes. Simply that at the end of the day, Morrison had a loyalty to the specific genre of superhero comics that Moore did not.

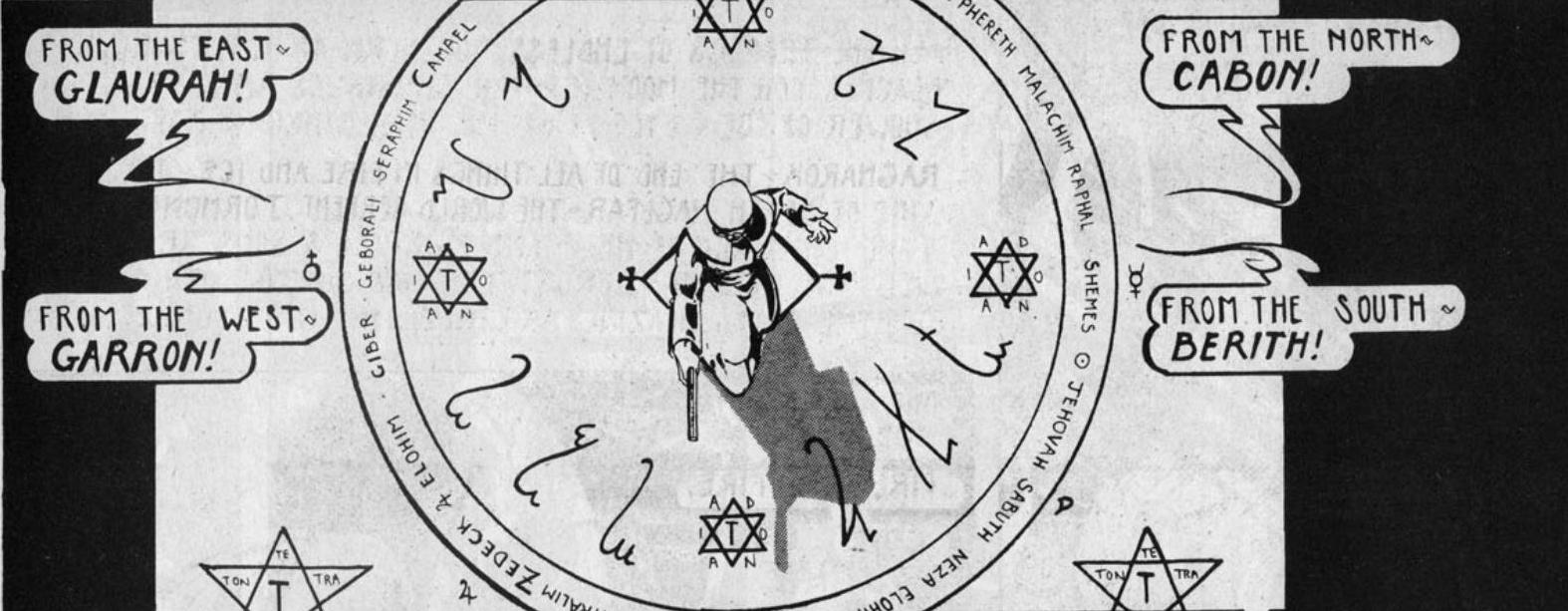

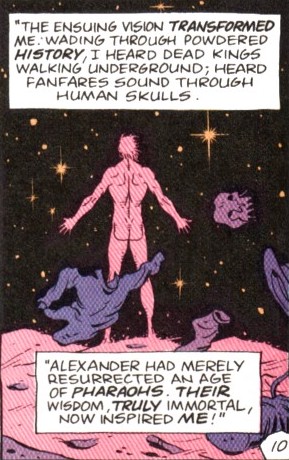

A second factor: Morrison was, from the start of his career, also overtly working with magic. This commenced somewhere around the beginning of 1979 when Morrison’s uncle gave him Frieda Harris and Aleister Crowley’s Tarot deck along with a copy of Crowley’s The Book of Thoth. Intrigued, he sent away for The Lamp of Thoth, a British occult magazine of the 80s. He was quickly drawn to the then emerging chaos magic scene, which had largely been kickstarted by the publication of Peter Carroll’s Liber Null the year before. Describing his first ritual, he recounts performing an “invitation to magic,” asking it to let him in. “I got the candles out, I did the magic words, I did the circle, I did the banishing and all that stuff,” he explains. Laying down after, “there was a kind of gravitational point in the air int he room which was drawing all the perspectives towards it as if there was a hole there or a crack. And there was the sense of black oil filling up the folds between the brain.” Scared, he appealed to Jesus, at which point an angelic lion’s head manifested, proclaiming “I am neither north nor south.”

Lest one believe that this is post facto justification contrived as part of his rivalry with Alan Moore—an accusation Moore leveled in his incendiary “last” interview, where he claims that “several months after I’d announced my own entry into occultism and the visionary episode which I believed Steve Moore and myself to have experienced in January, 1994, Grant Morrison apparently had his own mystical vision and decided that he too would become a magician”—Morrison’s early career work entirely supports his account of things. The Vatican Conspiracy contains a panel in which someone conducts a ritual to consecrate a circle taken from Reginald Scot’s 1584 The Discoverie of Witchcraft, conducted in what is recognizably a Circle of Solomon as described in The Lesser Key of Solomomn. And his 1983 zine Bombs Away Batman contains a page of book recommendations including the Illuminatus! Trilogy, Michael Talbot’s Mysticism and the New Physics, and Aleister Crowley’s Magick. (“Learn to manipulate reality with Old Uncle Aleister. If you’re sceptical it’s your duty to try it out for yourself.”) It’s not even possible to argue that Moore was instrumental in Morrison’s decision to be open about his occult interests: he talks about it in multiple interviews going as far back as 1988, where he talked to Arkensword about his “forays into the occult, specifically into Chaos Magick, the current that’s revolutionised the occult world during the last 6 or 7 years.”

And so all of Morrison’s actions, from his juvenilia through to his calculated and efficient post-Moore assault on the now crumbling gates of the mainstream comics industry, It is true that Morrison’s conception of magic differs from Moore’s; he’s less focused on art as the specific vehicle for magic and more focused on the traditional notion of directly affecting reality—Morrison and his friend Gordon Goudie both recall Morrison magically locating Goudie’s missing guitar in the early 80s. That is not to say that Morrison’s art is not at times overtly magical—he’s been unambiguous about viewing The Invisibles that way—but it means that he does not necessarily view every Zoids script and every Future Shock as a magical spell in the same way that Moore would eventually come to. Nevertheless, he was magically aware, and was viewing the world in a magical way for more than a decade before Moore did.

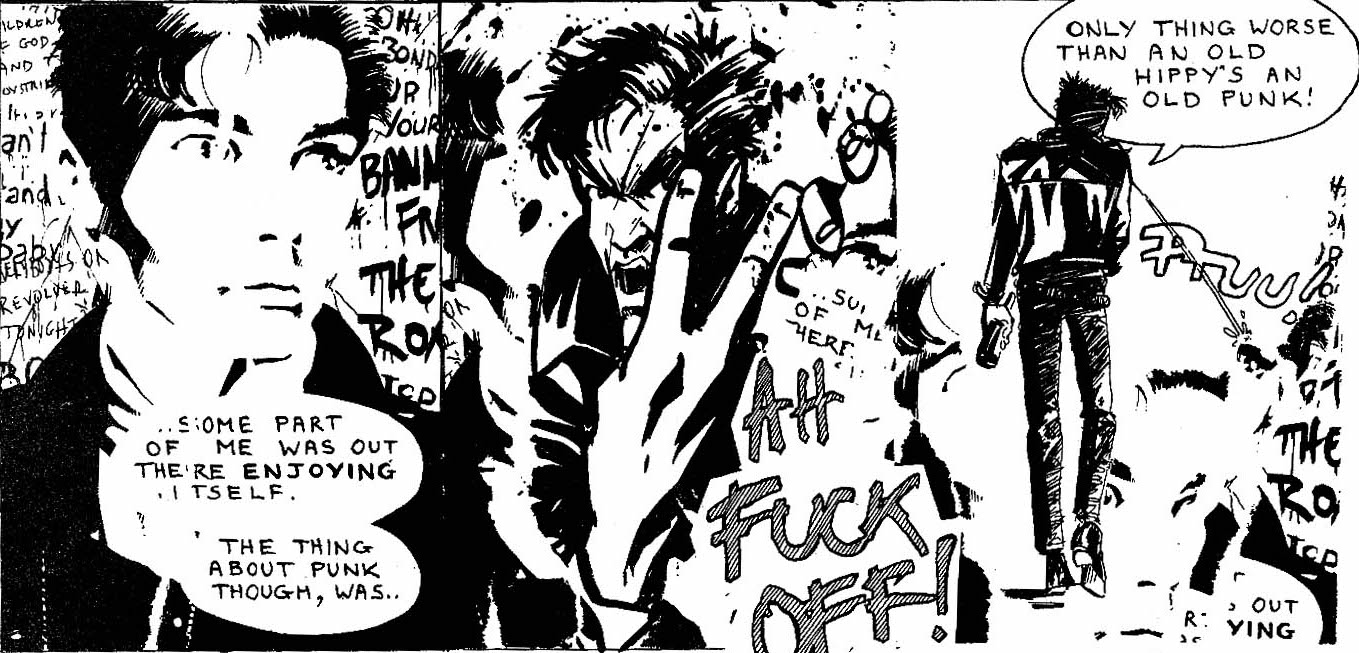

Third: he was a punk. Morrison has told the story of becoming a punk in multiple ways; in a 1988 one-pager called “Born Again Punk” for Heartbreak Hotel he said that “1977 was almost a religious thing—a conversion I suppose,” but in Supergods he dates it to 1978, saying that he’d initially dismissed punk “as some kind of Nazi thing after seeing a photograph of Sid Vicious sporting a swastika armband,” only coming around when seeing X-Ray Spex perform “The Day The World Turned Day-Glo” on Top of the Pops in 1978. In either account, however, the vigor of his newfound passion is clear. Writing in Supergods, he explains that “the world started to make sense for the first time since Mosspark Primary. New and glorious constellations aligned in my inner firmament. I felt born again.”

Morrison was, however, a curious sort of punk. As he admits in “Born Again Punk,” he did not actually dress the part, wryly joking, “I know people who claim to have seen me with spiky hair, a leather jacket and drainies in 1978… maybe while I sat in my bedroom, listening to Peel and ‘Streetsounds’.” And this is backed up—a common refrain of anybody telling early 80s Grant Morrison stories is the extent to which he was a shy and awkward sort of geek. This is not, of course, incompatible with being a punk, but it reflects a sort of aspirational relationship with the brash disruptiveness of punk—one captured in Supergods when he describes how “this, for me, was the real punk, the genuine anticool, and I felt empowered. The losers, the rejected, and the formerly voiceless were being offered an opportunity to show what they could do to enliven a stagnant culture. History was on our side, and I had nothing to lise. I was eighteen and still hadn’t kissed a girl, but perhaps I had potential. I knew I had a lot to say, and punk threw me the lifeline of a creed and a vocabulary—a soundtrack to my mission as a comic artist, a rough validation.”

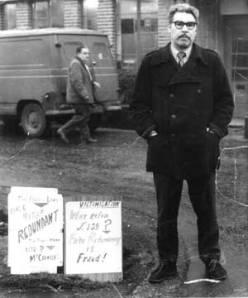

These factors in mind, turn to how he got to this point. His upbringing as the child of an antinuclear activist has come up before, but it’s worth pausing to look more at his father, who was an extraordinary figure in his own right. Walter Morrison volunteered for the army in World War II out of a hatred of fascism, but quickly came to find that, as he put it, “So I go into the military thinking we’ve got a crusading crowd of people here, who are even more aware than the civilian – that he’s prepared to get a gun and go and fight for that guy. And then to find in that situation that this guy knows less about freedom than what I’d come from, and what I’d been taught. And that everything I had been taught about the baddie, the Nazi and the fascists was plonk there in front of me, in this crowd of people who were supposed to be enlightened, informed and geared up to fight it. So how the hell do you move from that square to the enemy? When you find the enemy’s in your midst?”

These factors in mind, turn to how he got to this point. His upbringing as the child of an antinuclear activist has come up before, but it’s worth pausing to look more at his father, who was an extraordinary figure in his own right. Walter Morrison volunteered for the army in World War II out of a hatred of fascism, but quickly came to find that, as he put it, “So I go into the military thinking we’ve got a crusading crowd of people here, who are even more aware than the civilian – that he’s prepared to get a gun and go and fight for that guy. And then to find in that situation that this guy knows less about freedom than what I’d come from, and what I’d been taught. And that everything I had been taught about the baddie, the Nazi and the fascists was plonk there in front of me, in this crowd of people who were supposed to be enlightened, informed and geared up to fight it. So how the hell do you move from that square to the enemy? When you find the enemy’s in your midst?”

As one might expect from this, Walter Morrison had a difficult time in the army. In one of his most entertaining anecdotes, King George VI came to inspect his unit, and asked him how he liked the Army. As he tells it, “Without much hesitation I told him I didnae like it.” In another instance, after being sent to India, he was informed that his unit would be facing women and child protesters, and given the order to shoot the protesters if they advanced; his response was that he would be the first to open fire, first shooting any soldier that turned his gun on a woman or child and then shooting the officer who gave the order. The result was one of his several stints in the Glasshouse.

After the war, Morrison retired to a life of activism. The bomb was his most frequent target, but he was an unrepentant radical, pacifist, and anarcho-socialist. On one instance, after his friend Stuart Christie was arrested in Spain for trying to assassinate Franco, Morrison went to picket the Spanish embassy, where he was promptly arrested and subjected to a lengthy interrogation over his political affiliations. (Christie also largely corroborates Grant Morrison’s story of his father being threatened by men in black, although Christie sets the incident at a protest near the pier at which the nuclear submarines were serviced as opposed to a nighttime visit to the home.)

The influence Morrison’s father upon him is clear enough in his sense of radicalism and the iconoclastic. But their relationship was complicated; it was through his father’s activism that Morrison’s deep fear of the bomb arose, after all. And when he describes his parents’ divorce in Supergods the sense of blame is clear: “Dad’s marital betrayals were more than Mum could handle. Like the cvracked vases that she chucked in the bin for any sign of imperfection, Dad was irreparably fractured. He’d always dug the broken pieces out of the trash and painstakingly Scotch-taped them back together, but in his case the damage was irreversible.”

In decades to come, Morrison would mine his sense of confusion and pain over the divorce for his Batman run. All of this, however, lay far in the future; in his early career, his only opportunity on the character came in the UK 1986 Batman Annual, in which he published a three-page illustrated prose story alongside one in the equivalent Superman Annual. In this he was once again following in the footsteps of Moore, who’d published a similar diptych the previous year. These pieces are, to be sure, mediocre—particularly the Batman one, entitled “The Stalking,” which is a bland piece about Catwoman breaking into the Batcave marred by a clumsiness of prose. The Superman piece, “Osgood Peabody’s Big Green Dream Machine,” is better, with a sense of endearing absurdity—at one point Peabody, who has invented a machine that can see into people’s dreams and proposes to use it to find Superman’s weakness, is asked whether he sleeps in his labcoat, and offendedly insists that of course he does, and the story ends with the reveal that everyone has actually been looking at Krypto’s dreams, and that the frequent images of bones were not, in fact, symbols of Superman’s underlying fear of death. It’s witty, but clearly juvenile—the work of a writer at the beginning of his career. (Moore, meanwhile, published “For The Man Who Has Everything” the same month.)

That this would still be true in 1985 when Morrison’s career had begun in 1978 is striking. By 1985 Moore was a titan. Not yet thirty-three, he’d hit it big at DC after revolutionizing the British comics industry, and was preparing to write the work that would end the Cold War. Morrison, meanwhile, had not meaningfully advanced from the upstart teenager who’d landed a comic in Near Myths seven years previous. That magazine had folded, he’d been sacked from the Govan Press, and his comics career consisted of a few Starblazer comics knocked off for spare cash. His career floundered, looking like it would be over in a flash, unnoticed by essentially everyone. And then, in 1985, he returned to the industry to try again. What had happened in the meantime?

That this would still be true in 1985 when Morrison’s career had begun in 1978 is striking. By 1985 Moore was a titan. Not yet thirty-three, he’d hit it big at DC after revolutionizing the British comics industry, and was preparing to write the work that would end the Cold War. Morrison, meanwhile, had not meaningfully advanced from the upstart teenager who’d landed a comic in Near Myths seven years previous. That magazine had folded, he’d been sacked from the Govan Press, and his comics career consisted of a few Starblazer comics knocked off for spare cash. His career floundered, looking like it would be over in a flash, unnoticed by essentially everyone. And then, in 1985, he returned to the industry to try again. What had happened in the meantime?

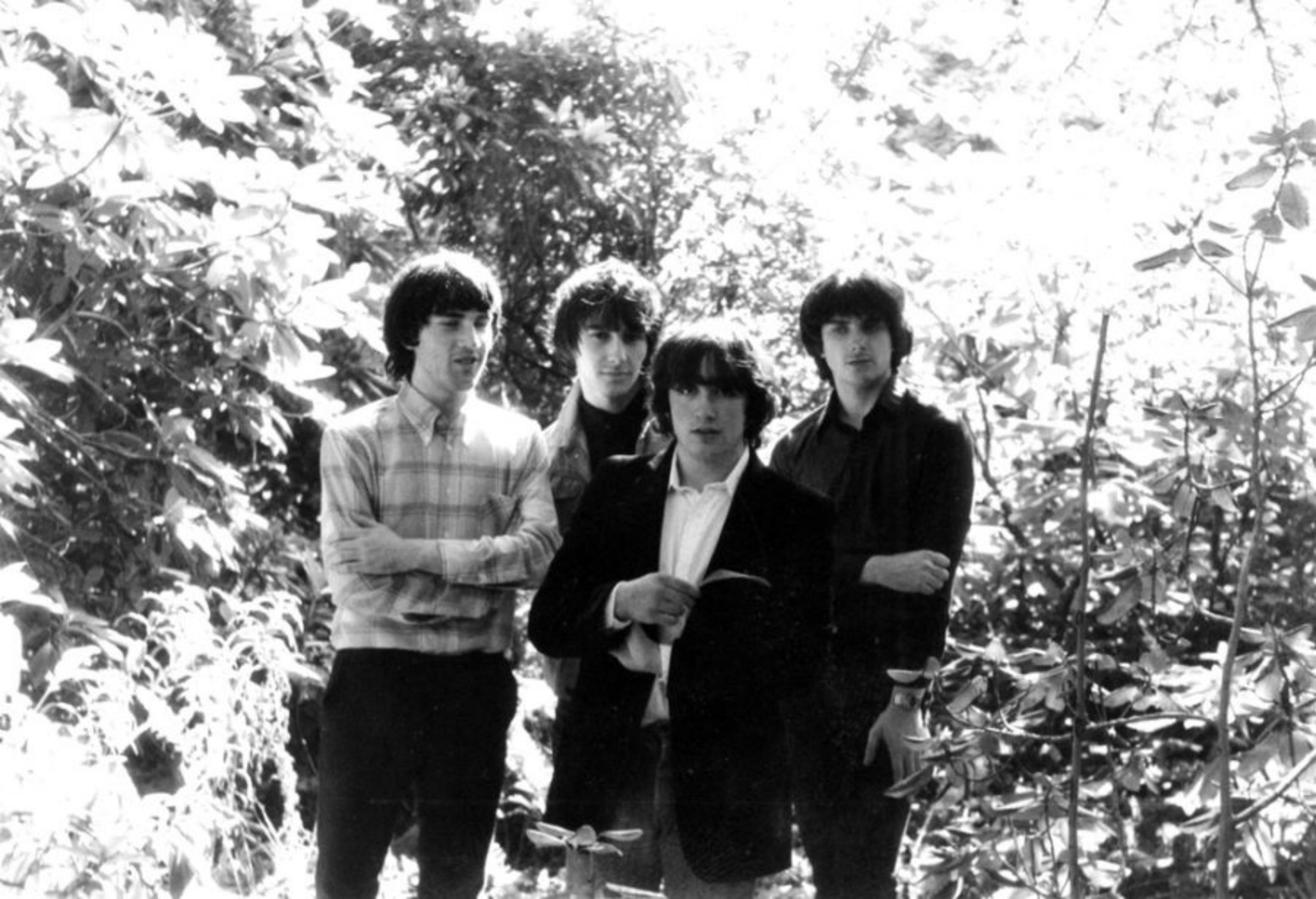

For the most part, Morrison tried to become a rock star. The main vehicle for this was the Mixers, a band spearheaded by Dannie Vallely and Ulric Kennedy in which Morrison played rhythm guitar. The band, named for a throwoaway line in A Clockwork Orange, split the difference between Morrison’s newfound punk interests and the 60s mod aesthetic Morrison was otherwise drawn to—“the Hollies on speed,” as one review apparently described them. Morrison’s account of the band is modest—as he puts it, “We weren’t great musicians, but we had a lot of enthusiasm. The trouble is, everyone was coming from a similar place of damage. We weren’t very good at being a band… we were a kind of crappy band, but we looked beautiful and we sounded really great.”

Given that virtually all that survives of the band are CD-Rs of their 1984 album Speed, Madness, Flying Saucers, which was in turn copied from a cassette tape, Morrison’s boast of quality is difficult to evaluate. Comparing the Mixers straightforwardly to contemporaneous bands like the Smiths or Echo and the Bunnymen runs aground against the fact that those bands had professional studio recordings The Smiths eponymous first album cost six thousand pounds and involved ditching the entire first studio session and starting over; even the handful of Mixers tracks to emerge on CD-released compilations are clearly hastily produced efforts by a bunch of kids on the dole.

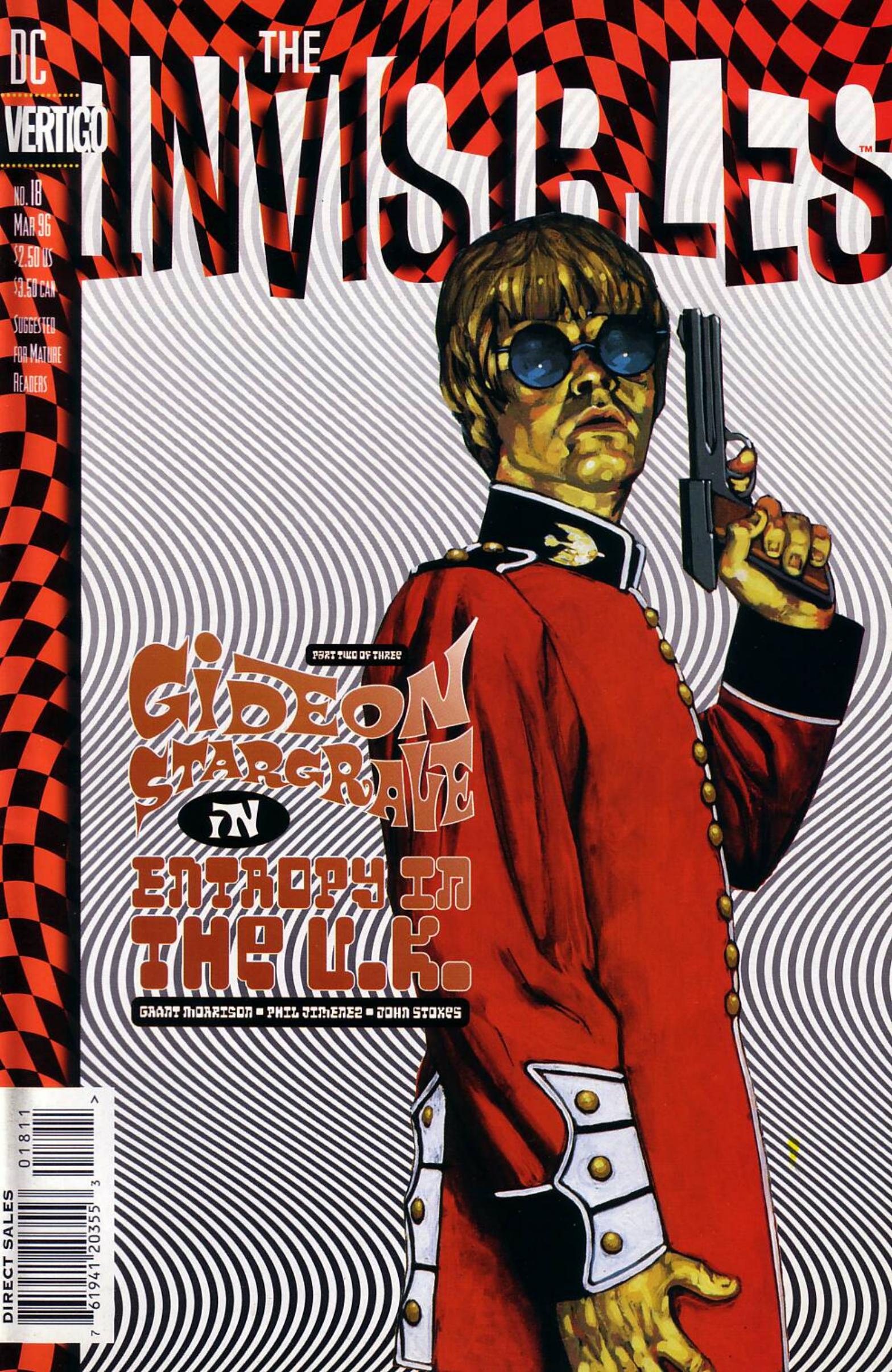

Nevertheless, even the most charitable reading of the Mixers would conclude that they were simply the wrong band for the time. Morrison cultivated a flamboyantly retro mod aesthetic, dressing much like Gideon Stargrave eventually would in The Invisibles—his first real effort at the ostentatious public personality he sought—but in doing so he just missed the New Romantic scene. Similarly, the band’s 60s retro sound might have fit well in glam, which was fundamentally a classic rock revivalism with more flamboyance, but again, was far too late to catch this wave. Instead, as pop music made the swing towards the postpunk influenced second British invasion, the Mixers attempted to jump ahead straight to Britpop and fell into the decade-wide chasm between them, never to be seen again.

But while the Mixers may not have been successful musically, they provided an important stepping stone between the nineteen year-old Morrison—a shy geek drawing comics—and the persona he would eventually craft for himself. As mentioned, his Mixers-era persona was a flamboyant mod—outlandish and brightly colored jackets—Frank Quitely describes it as “dandyish in a kind of very skinny Oscar Wilde kind of way.” As he put it, “I formed a band, and just started to live, and get out, and dress up and be the person I’d always wanted to be.” He’d hang around Glasgow, a “mod shaman” going to pubs like the Rock Garden and reading Tarot for anyone seeking advice.

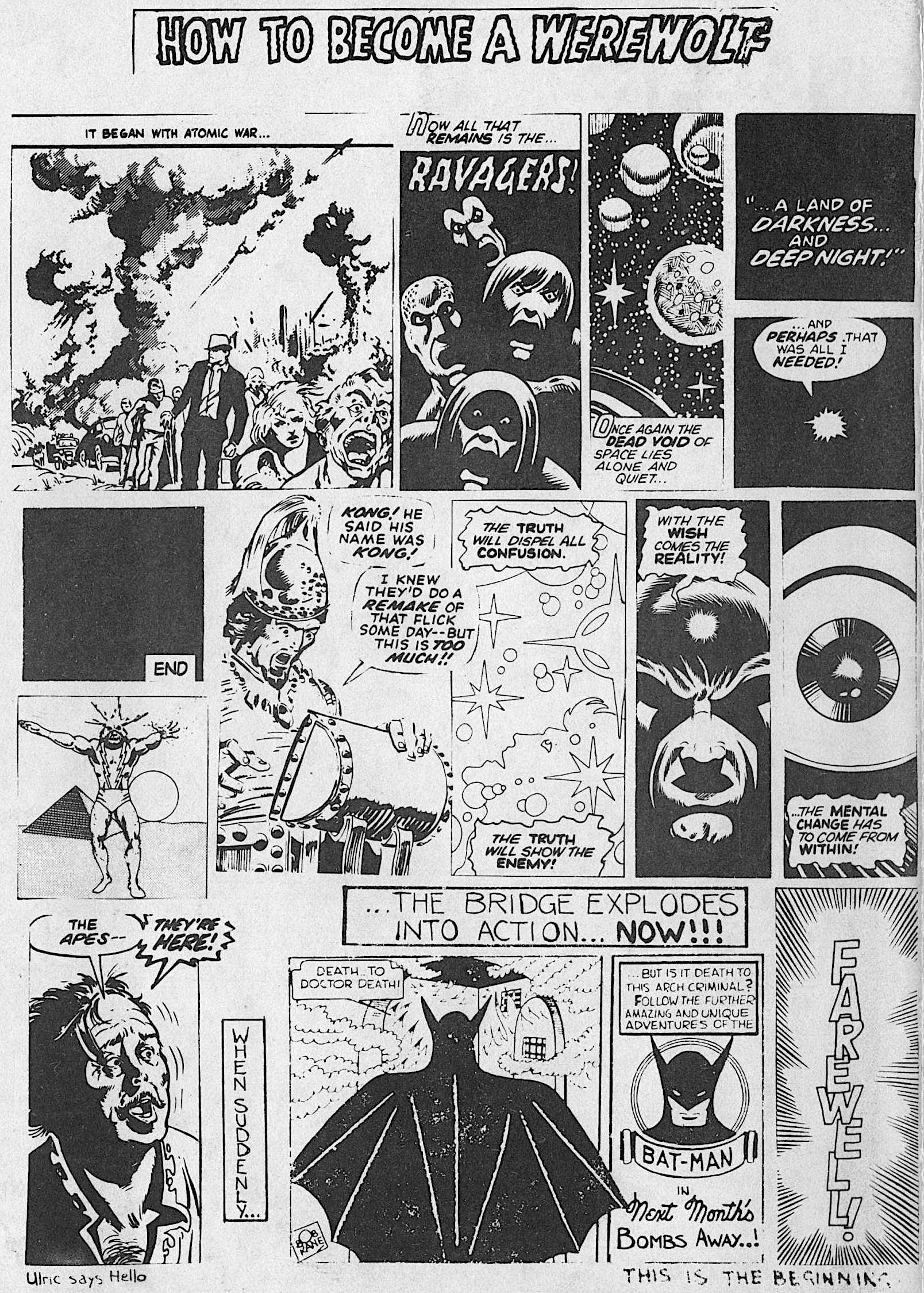

The band as a whole cultivated a similarly brash attitude. In Bombs Away Batman, Morrison cheekily presents an interview with the band in which they affect a posture of brash arrogance. At one point, Morrison proclaims “the charts are full of dross. I don’t believe there are more than a handful of bands on the whole planet who really care about what’s going on and want to change it. And the so-called ‘subversive’ bands like Crass wouldn’t know subversion if they fell over it, that’s why they never achieve anything.” But the ambition for overall fame was clear—at one point, discussing their hatred of how the musical landscape had fragmented into endless subcultures, Ulric Kennedy proclaims that “we just want there to be a mainstream so everyone likes us.” Within the braggadocio, however, Morrison repeatedly outs himself as someone with more intellectual goals—at one point he muses about how “in all the magazines it’s ‘fun fassions of the ‘50s’ and all the crap. And everyone’s falling for it. It shows you how easy it is to rope the kids in on a general shift towards a puritanical right wing value system—Thatcher and Reagan trying to create the old world again.” Or, at one point, the genuinely amazing exchange in which Morrison and the interviewer, who is, recall, Morrison proceed to finish each other’s sentences in the course of a lengthy reverie on Von Neumann, quantum physics, and the UK music press.

The band as a whole cultivated a similarly brash attitude. In Bombs Away Batman, Morrison cheekily presents an interview with the band in which they affect a posture of brash arrogance. At one point, Morrison proclaims “the charts are full of dross. I don’t believe there are more than a handful of bands on the whole planet who really care about what’s going on and want to change it. And the so-called ‘subversive’ bands like Crass wouldn’t know subversion if they fell over it, that’s why they never achieve anything.” But the ambition for overall fame was clear—at one point, discussing their hatred of how the musical landscape had fragmented into endless subcultures, Ulric Kennedy proclaims that “we just want there to be a mainstream so everyone likes us.” Within the braggadocio, however, Morrison repeatedly outs himself as someone with more intellectual goals—at one point he muses about how “in all the magazines it’s ‘fun fassions of the ‘50s’ and all the crap. And everyone’s falling for it. It shows you how easy it is to rope the kids in on a general shift towards a puritanical right wing value system—Thatcher and Reagan trying to create the old world again.” Or, at one point, the genuinely amazing exchange in which Morrison and the interviewer, who is, recall, Morrison proceed to finish each other’s sentences in the course of a lengthy reverie on Von Neumann, quantum physics, and the UK music press.

The ambitious arrogance of this interview is of a piece with Bombs Away Batman, which is probably the best single encapsulation of Morrison’s early 80s obsessions. In addition to a punk collage aesthetic, Morrison finds time to offer book recommendations (in addition to those already mentioned, A Clockwork Orange, High Windows by Philip Larkin, Red Shift by Alan Garner [who he interviewed for an issue of White Tree a half-decade earlier], The Stand, Richmal Crompton’s Wlliam books, Charles Berlitz’s Doomsday 1999, and, inevitably, the Jerry Cornelius books), a page on comics that consists purely of praise for Alan Moore (who “has singlehandedly lifted comics into a realm only partly glimpsed by previous writers,” although even here Morrison can’t resist complaining that he’s unimpressed with the “Warpsmiths” strip), a page of poetry that ends with the encouragement to send in “more of these great poems, especially one about God, the army, and nuclear war. If you can’t write them yourselves try looking through old school magazines or poetry fanzines and copy the best ones—participate!”, and a cutup comic entitled “How to Become a Werewolf.” It’s everything one wants from a young Grant Morrison—a burst of snarky, presumptuous, and intellectualized DIY punk.

The only thing it isn’t, unfortunately, is very much like the Mixers, whose retro songs about the trials and tribulations of love feel nothing like the iconoclastic “I’ll fight the whole damn world” zeal of their rhythm guitarist’s fanzine. And so it is perhaps unsurprising that the band steadily sputtered to a halt. As Morrison tells it, they were “spinning in multicolored circles, devolving to nothing more than posters, threats, and endless vague rehearsals.” Until eventually they’d stopped. Various combinations would try a few side projects over the next few years—the Favues, Ochre 5, and Jenny & The Cat Club, all with basically the same sound, but none left any mark, and by 1985 Morrison’s music career was dead and buried.

The only thing it isn’t, unfortunately, is very much like the Mixers, whose retro songs about the trials and tribulations of love feel nothing like the iconoclastic “I’ll fight the whole damn world” zeal of their rhythm guitarist’s fanzine. And so it is perhaps unsurprising that the band steadily sputtered to a halt. As Morrison tells it, they were “spinning in multicolored circles, devolving to nothing more than posters, threats, and endless vague rehearsals.” Until eventually they’d stopped. Various combinations would try a few side projects over the next few years—the Favues, Ochre 5, and Jenny & The Cat Club, all with basically the same sound, but none left any mark, and by 1985 Morrison’s music career was dead and buried.

And so Morrison retreated back to comics. This was a slow process, to be sure. He started with “The Liberators” in Warrior, where he had the misfortune of arriving precisely as the magazine folded in February of 1985. A few months later he landed “The Stalking” and “Osgood Peabody’s Big Green Dream Machine,” and at the start of 1986 landed another text piece in Captain Britain and his first Future Shock in 2000 AD. Along the way, he also tried to reactivate various older projects—Gideon Stargrave made a two-page reappearance in the Food for Thought anthology, which also featured the Alan Moore/Bryan Talbot collaboration “Cold Snap” and an extremely early work of Warren Ellis’s from long before he was famous enough to get away with sexually abusing dozens of women. And, of course, he did the series of Zoids strips for Marvel UK, his first work to really catch eyes and turn heads.

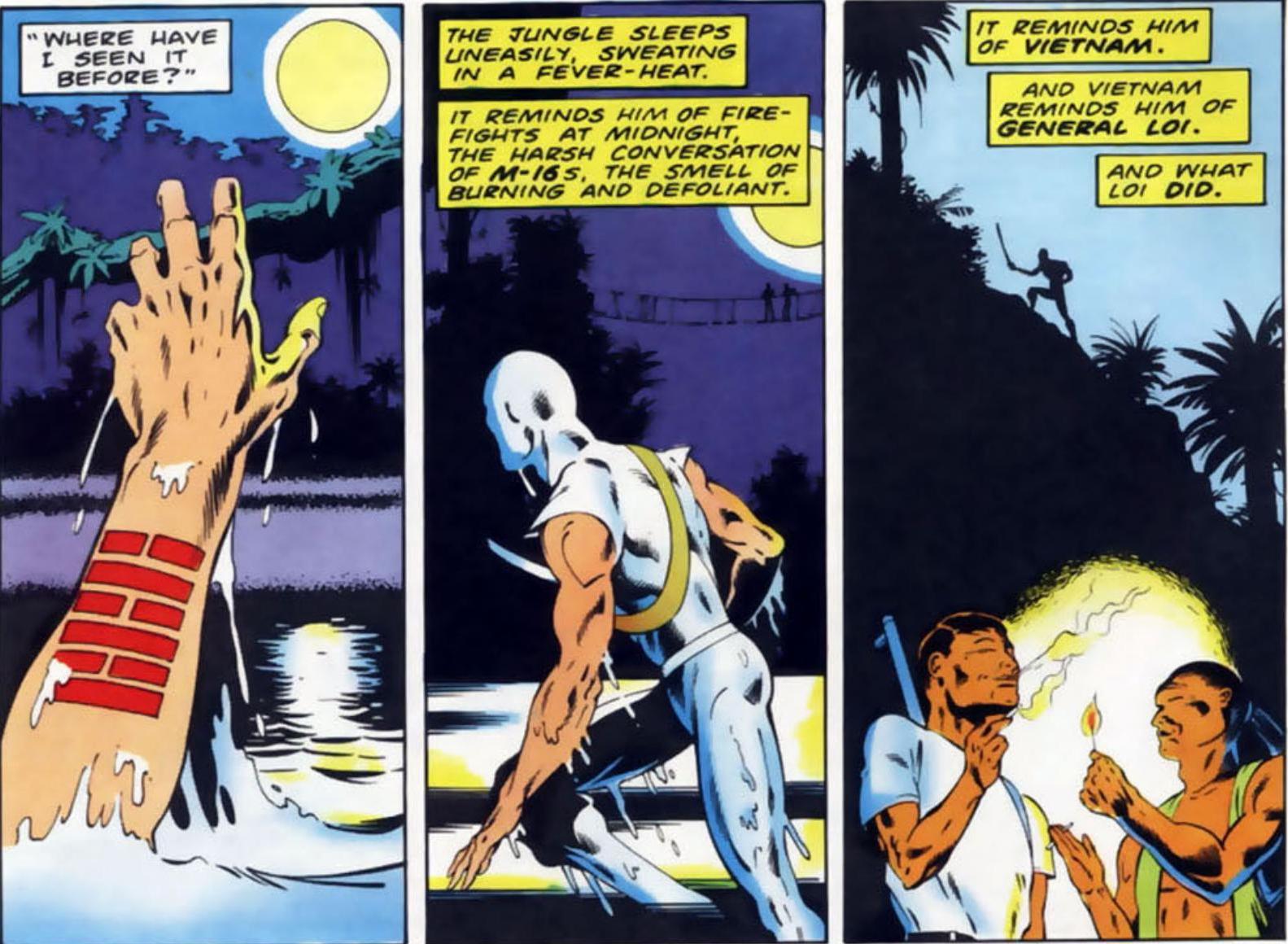

Success breeds success, and Morrison soon found other work at Marvel UK. In June of 1987, the same month that Watchmen and Moore’s Swamp Thing run wrapped, Morrison penned a short five-page piece entitled “Meditations in Red” for Action Force Weekly. This mostly served as an introduction to Marvel’s Shang-Chi to set up a run of Master of Kung Fu reprints that would begin the next week, and is basically an infodump with no narrative ideas of Morrison’s own. But what this lacks in cleverness it makes up for in a sort of professional efficiency. Morrison is given a resolutely unglamorous job to do, and he does it. It’s not a job that can be done spectacularly—this is leading into reprints, after all, not some brand new Morrison-penned take on Shang-Chi where he can dramatically recontextualize his origin. But he does it well, clearly, and with at least a few moments of wit.

A year later, once the magazine had converted to a monthly publication (and one that got simultaneously published in the US as G.I. Joe European Missions), Morrison penned a longer piece entitled “Old Scores.” This one followed the G.I. Joe character Storm Shadow, a ninja notable for swinging back and forth between Cobra and G.I. Joe, as he executes a revenge mission on a man named General Loi. It’s clever, efficient, and once again clearly Morrison doing a job—blood-soaked vengeance in the context of military adventure is far from the sort of thing he naturally gravitates to. Morrison fits more of hisself into it than one might expect, and certainly more than he does into “Meditations in Red”—he unsurprisingly makes a lot of the detail that Storm Shadow has a tattoo of hexagram 63 of the I Ching, and a clever ending in which Storm Shadow makes it into the general’s inner sanctum and then proclaims that he’s not going to kill him yet, he just wants him to know that he’ll never be safe, to which the general replies by shooting himself in horror at the prospect of living in fear like that. But for the most part, like “Meditations in Red,” it’s a piece that demonstrates Morrison’s professionalism.

Of course, professionalism was ultimately the key to breaking into American comics. DC had learned their lesson when it came to visionary geniuses; what they wanted were company men. If they were company geniuses, all the better, but what was most necessary were writers who would do as they were told. It is not that similarly utilitarian works are absent from Moore’s early ouvre, but as always, Moore cannot keep from showing off, and gravitated constantly towards over-delivering. Morrison, meanwhile, was just as willing to turn in a few pages of crap and get a paycheck as he was to boldly question the basic premises of a series, modulating what he offered based on what the people paying him actually wanted. “Clever and challenging” comics were just one arrow in his quiver.

Of course, professionalism was ultimately the key to breaking into American comics. DC had learned their lesson when it came to visionary geniuses; what they wanted were company men. If they were company geniuses, all the better, but what was most necessary were writers who would do as they were told. It is not that similarly utilitarian works are absent from Moore’s early ouvre, but as always, Moore cannot keep from showing off, and gravitated constantly towards over-delivering. Morrison, meanwhile, was just as willing to turn in a few pages of crap and get a paycheck as he was to boldly question the basic premises of a series, modulating what he offered based on what the people paying him actually wanted. “Clever and challenging” comics were just one arrow in his quiver.

But what, in all of this, did he want? What sort of writer did Morrison desire to be? The answer is clearly not that he wanted to be a docile company man turning out an endless series of made to order pieces without fuss. He was, after all, following in Moore’s footsteps. But it is worth being clear on exactly what that means. Alan Moore is unique among combatants in the War in that when he began in comics, there was no precedent for what he was doing. Alan Moore was the only one who could not look to his own career for guidance and inspiration. For all his ferocious ambition and desire to impress, he could not have imagined that he would become the sort of star that he did for the simple reason that the sort of star he became didn’t exist before him.

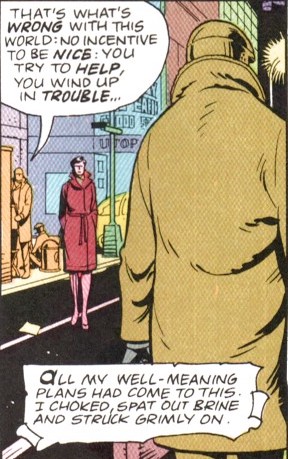

Morrison, meanwhile, knew exactly where this road could lead him. And yet it would also be a mistake to treat Morrison’s career as a series of ruthlessly selected choices aimed at supplanting Moore as the luminary of the British comics scene. At the end of the day, Morrison’s early moves were motivated by far more prosaic concerns. Having, during his Mixers days, tried to hold down a civil service job, he had by this point “decided that I would never, ever, ever work again.” Much as Moore decided that with a kid on the way he faced his last chance to try to be a writer, Morrison wanted to not be broke. He was on the dole and living with his mother, and wanted not to be. So he took the jobs that existed. If Marvel would give him some money for retelling Shang-Chi’s origin story or doing a quick G.I. Joe story then he would do it.

Morrison, meanwhile, knew exactly where this road could lead him. And yet it would also be a mistake to treat Morrison’s career as a series of ruthlessly selected choices aimed at supplanting Moore as the luminary of the British comics scene. At the end of the day, Morrison’s early moves were motivated by far more prosaic concerns. Having, during his Mixers days, tried to hold down a civil service job, he had by this point “decided that I would never, ever, ever work again.” Much as Moore decided that with a kid on the way he faced his last chance to try to be a writer, Morrison wanted to not be broke. He was on the dole and living with his mother, and wanted not to be. So he took the jobs that existed. If Marvel would give him some money for retelling Shang-Chi’s origin story or doing a quick G.I. Joe story then he would do it.

On the other hand, for all that he wanted to get off the dole, he didn’t want to do it enough to get a proper job. He wanted to be an artist. As he notes moments after repeating his determination not to have a proper job again, he turned to comics as “the only hope I had of doing anything meaningful.” Talking about his decision to focus on writing instead of drawing, he notes that “I wanted to just tell stories, and I didn’t want to draw other people’s stuff,” whereas writing “allowed me to tell more stories and get more work done and get more out of my head on to the page.” The balance here is, of course, no contradiction—it’s the rock and hard place that every freelancer is caught between, looking for paying work and for the opportunities to do something with the head full of ideas that’s driving them.

But for Morrison, all of this was balanced against another concern. He didn’t just want to make art; he wanted to be an artist. This was at the heart of his time in the Mixers, using rock, fashion, and magic to craft a new public persona, replacing the shy and unconfident geek he was with the a glamorous and ostentatious star. It wasn’t just Alan Moore’s critical success or fame he wanted, but the specific public persona that Moore crafted—the instantly recognizable man dressed in a stylish suit (in the 80s, famously a white one with short-cut sleeves) who proclaimed himself “a comic book messiah for the 1990s.” Morrison didn’t stop wanting to be a rock star; he just decided to do it in comics instead

But this isn’t the sort of goal you achieve doing one-shots in Action Force Weekly. The sort of writers who become iconic stars in their own right aren’t just the ones who do competent work on a number of books. They aren’t even ones who get ideas out of their heads. Becoming a rock star of comics requires a measure of greatness—requires creating something that inspires love and devotion, and that sells well doing it. Morrison took his task seriously, which in turn meant taking the need for a great work seriously. Not as an all-consuming desire, or a dream to be forever chased as he meticulously honed his craft, but as another assignment to execute with professional competence.

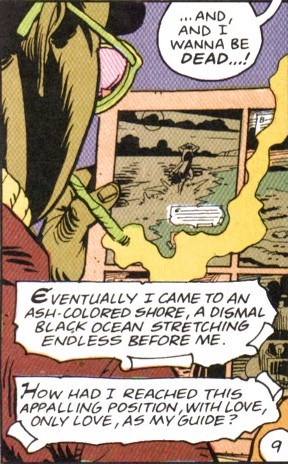

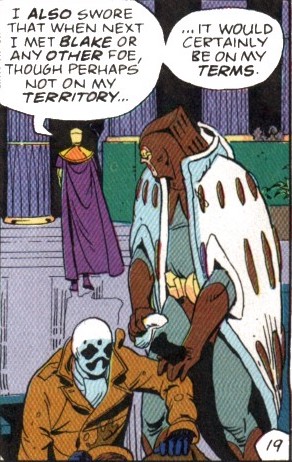

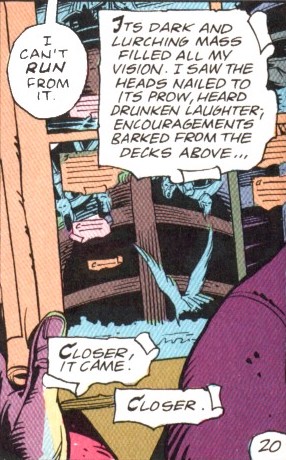

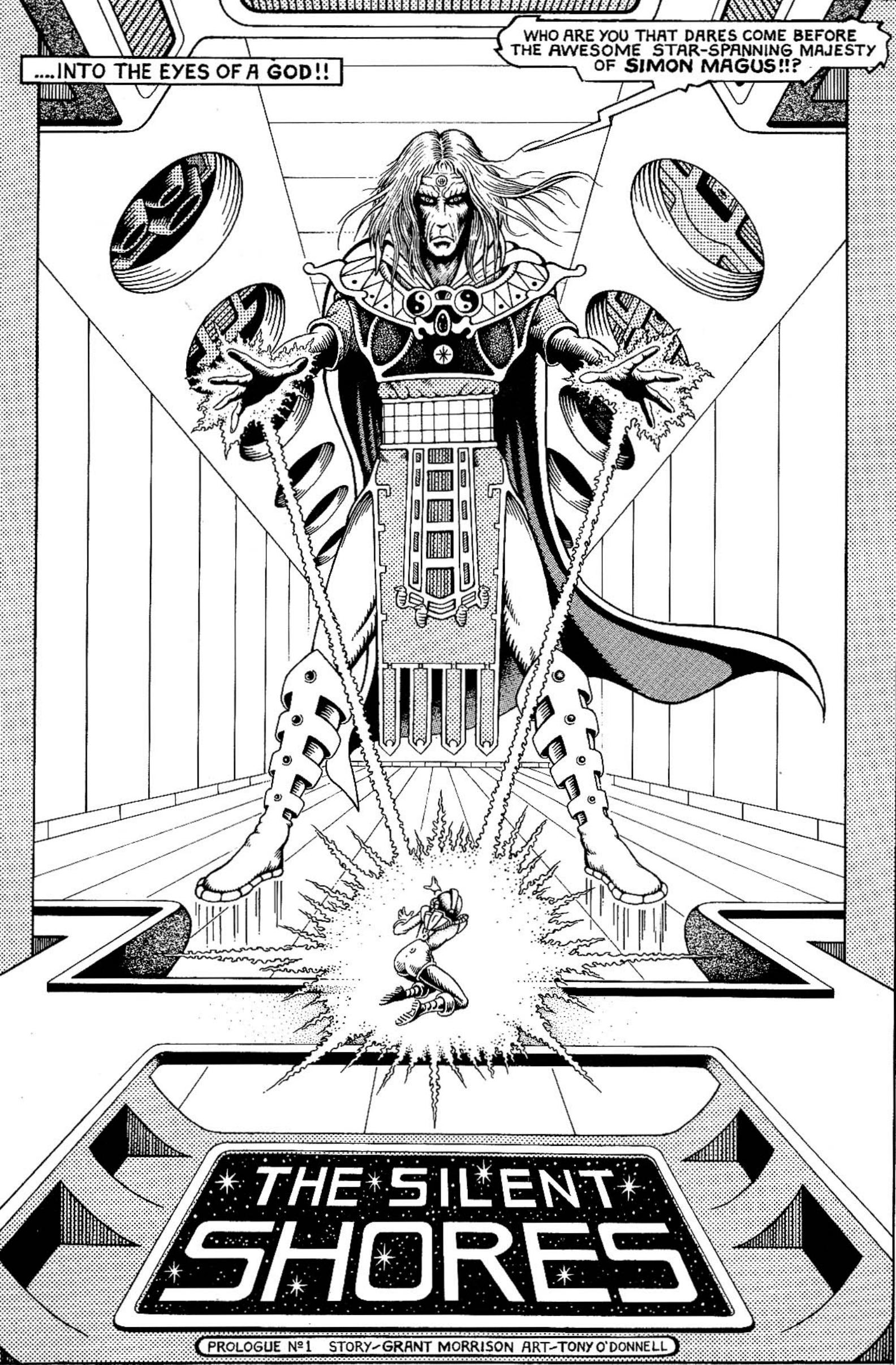

His first real effort at this was longstanding—a pitch dating back to his days at Near Myths, where he befriended another local comics artist, Tony O’Donnell, and with him pitched a sci-fi epic called Abraxas. As Morrison imagined it, this would be a hundred page sci-fi epic “involving aliens, gnosticism, Celtic mythology, the End of the Universe, and girls in leather underwear.” The project fell through when Near Myths folded, but Morrison kept the project alive, eventually resurrecting it for a short-lived imprint called Harrier Comics that produced black and white originals. There it ran as the backup feature for a 1987 comic entitled Sunrise, but this wound up being a short-lived arrangement. For one thing, O’Donnell was painfully slow with the art, later admitting that “Whenever I worked on the project I became so obsessed with trying to produce my very best work that I spent ages on each page.” For another, Harrier quickly went out of business after Sunrise’s second issue in May of 1987 (the same month as Watchmen #11) and as a result all that exists of this would-be great work is sixteen pages of prologue material.

His first real effort at this was longstanding—a pitch dating back to his days at Near Myths, where he befriended another local comics artist, Tony O’Donnell, and with him pitched a sci-fi epic called Abraxas. As Morrison imagined it, this would be a hundred page sci-fi epic “involving aliens, gnosticism, Celtic mythology, the End of the Universe, and girls in leather underwear.” The project fell through when Near Myths folded, but Morrison kept the project alive, eventually resurrecting it for a short-lived imprint called Harrier Comics that produced black and white originals. There it ran as the backup feature for a 1987 comic entitled Sunrise, but this wound up being a short-lived arrangement. For one thing, O’Donnell was painfully slow with the art, later admitting that “Whenever I worked on the project I became so obsessed with trying to produce my very best work that I spent ages on each page.” For another, Harrier quickly went out of business after Sunrise’s second issue in May of 1987 (the same month as Watchmen #11) and as a result all that exists of this would-be great work is sixteen pages of prologue material.

Still, what exists speaks to Morrison’s ambition. The first prologue is unrepentant space opera in which a woman, Gendrill, is trying to convey a tape when her spaceship is set upon by aliens (Morrison developed this in 1979, two years after Star Wars). She is ultimately rescued by the imposing Simon Magus (Jim Starlin’s Adam Warlock run had been in 1975), where she meets the eponymous Abraxas and they work together to recover the tape. The installment ends with a shadowy figure in a helmet arriving to see that they’ve missed the tape and Abraxas and Simon Magus musing that “it’s started.” Intriguingly, the next part then cuts to an ordinary woman named Shirley living in a borrowed house where she’s menaced by UFOs and, on the final page, the same shadowy figure from the previous prologue, who captures her for some unknown purpose. It’s scraps, and derivative scraps at that, but there are enough moving parts that it’s clear the comic was aiming high.

Twice, then, Morrison had grabbed at the brass ring only to see it slip from grasp: the failure to launch Zoids Monthly and the failure to get Abraxas anywhere near completion. On the one hand this was undoubtedly frustrating. On the other, two opportunities so soon after returning to the comics industry was a sign that things were working—that patience would eventually be rewarded. And so Morrison kept at it, working closely to the career path prescribed by Moore, penning short pieces, honing his skill, looking to impress the companies at which he could make the mark he so craved.

In all of this, what is perhaps most notable is what is absent: any idiosyncratic or personal work. The closest thing is Abraxas, which was Morrison trying to wrap up an old project. Otherwise, from 1985 to 1988 his only two such works are the Gideon Stargrave strip in Food for Thought and “Born Again Punk.” Everything else was penned for a mainstream publication, a plausible audition piece. In contrast, Moore all over the map, continuing Maxwell the Magic Cat and Sounds long after he’d secured better gigs, creating things like The Bojeffries Saga that existed for Moore’s own interests, as opposed to out of any ambition to impress a publisher, and still creating goofy stuff with his Art Lab pals like “March of the Sinister Ducks.” Morrison, meanwhile, maintained a laser focus on what he wanted: a big, high profile project, working the smaller pieces to try to find the one that would crack the lock, impress the right editor, and get him through the door.

In all of this, what is perhaps most notable is what is absent: any idiosyncratic or personal work. The closest thing is Abraxas, which was Morrison trying to wrap up an old project. Otherwise, from 1985 to 1988 his only two such works are the Gideon Stargrave strip in Food for Thought and “Born Again Punk.” Everything else was penned for a mainstream publication, a plausible audition piece. In contrast, Moore all over the map, continuing Maxwell the Magic Cat and Sounds long after he’d secured better gigs, creating things like The Bojeffries Saga that existed for Moore’s own interests, as opposed to out of any ambition to impress a publisher, and still creating goofy stuff with his Art Lab pals like “March of the Sinister Ducks.” Morrison, meanwhile, maintained a laser focus on what he wanted: a big, high profile project, working the smaller pieces to try to find the one that would crack the lock, impress the right editor, and get him through the door.

Slowly but surely over this process, he became recognizably Grant Morrison. Perhaps the clearest example of this, more even than Zoids, are a trio of stories he wrote for Doctor Who Magazine. By this time the publication was not the comics-centric one in which Alan Moore got his first publication as a writer, but rather a publicity piece for the television show running reviews, episode previews, and historical features about the show’s nearly twenty-five year long history. It still ran a monthly comic strip adventure for Doctor Who, however. In 1986 this strip was generally drawn by John Ridgway, with a rotating set of writers including Alan McKenzie, Simon Furman, Jamie Delano, and, at the end of the year, Morrison.

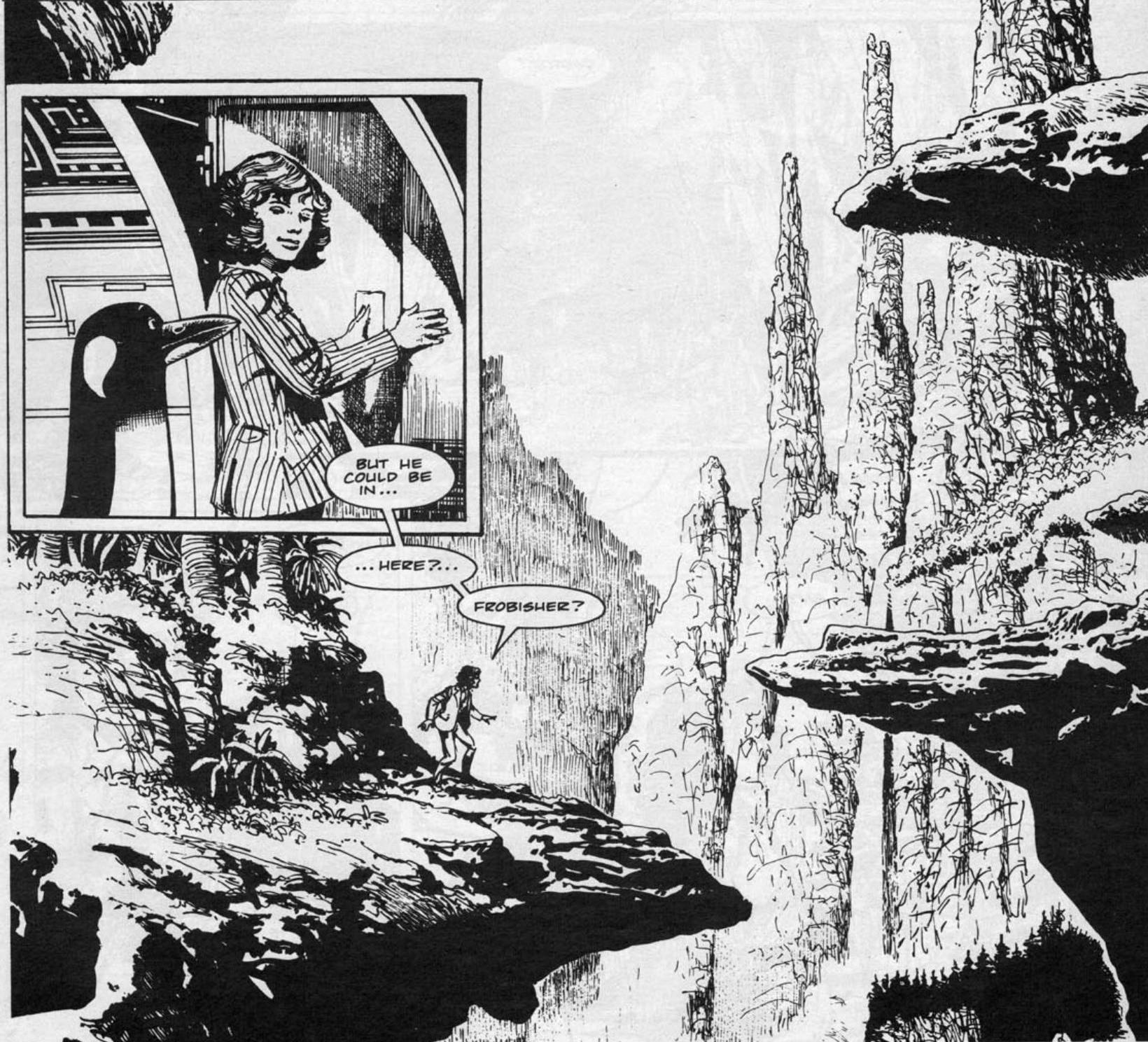

Morrison’s first piece for the magazine was called “Changes,” and starred Colin Baker’s iteration of Doctor Who along with his television companion Peri and a comics-exclusive character, a shapeshifting penguin named Frobisher. Its setup is simple enough: a shapeshifting alien called a Kimbra Chimera makes it onto the TARDIS, and Doctor Who and his friends must stop it. In terms of its basic plot, there’s a degree of sloppiness to it—the climax seems to arrive mostly because Morrison is running out of pages, and is not so much a payoff as the Doctor fiddling with a machine and expelling the monster into the time vortex. But the comic is not so much notable for its plot as for its sense of ideas and scale. Morrison picks up on the long tradition within the show of suggesting an infinite depth to the TARDIS, revealing that it contains, among other things, “dimensional simulations” of everywhere it has ever been along with a storage facility for various endangered species Doctor Who picks up with the intention of rehoming them on hospitable planets—all ideas that were simply unrealizable on the show’s infamously scant BBC budget. The story’s opening also sees Peri rummaging through the TARDIS’s storage, finding a previously unknown Shakespeare play along with paintings of Doctor Who by Van Gogh and Michaelangelo. The overall effect is to widen the sense of what is possible in Doctor Who, viewing its setting as far vaster than the confine of the television show.

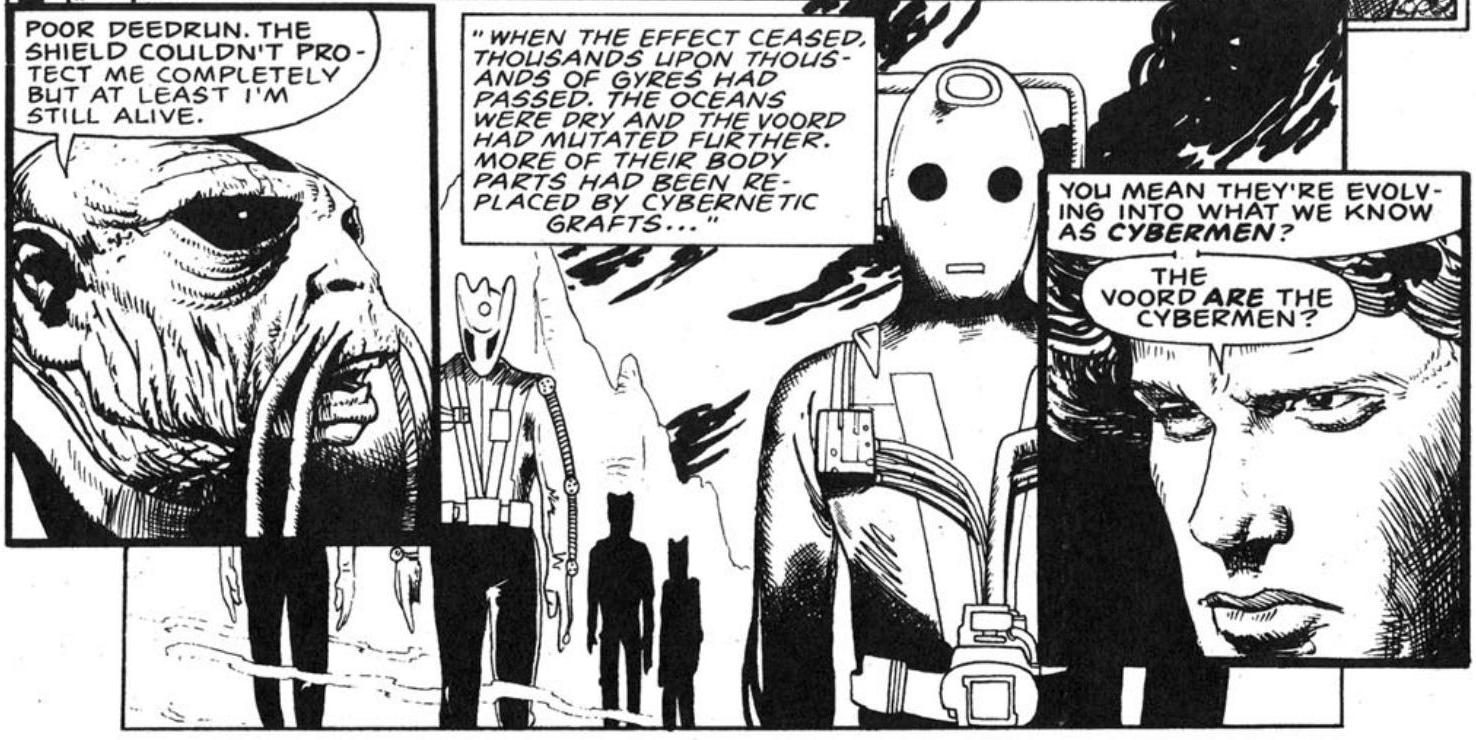

Morrison’s second Doctor Who Magazine piece came a few months later, in August of 1987, and is by some margin Morrison’s magnum opus with the character. Over three parts, The World Shapers cobbles together an idiosyncratic tapestry of Doctor Who history, with references to stories as far back as 1964’s The Keys of Marinus along with a reference to “The Fishmen of Kandalinga,” a prose story from the 1966 Doctor Who Annual in which the villains of The Keys of Marinus, the Voord, menace the eponymous fishmen. The story purports to explain a throwaway bit of continuity in the 1968 story The Invasion, in which the Cybermen claim to have met Doctor Who on something called “Planet 14,” and brings back the Patrick Troughton-era companion Jamie McCrimmon, now an old man called “Mad Jamie” for his fantastic tales of his time on the TARDIS. All of this is in service of a story that proposes an origin story for the Cybermen, who Morrison reveals are an evolution of the Voord provoked by the eponymous worldshapers, time-warping terraforming devices that are only supposed to be used on uninhabited planets.

It’s a stunningly ambitious story, providing in addition a heroic death for Jamie and a final page reveal that “within five million years, the Cybermen will have evolved again. Beyond the need for bodies. They will become pure thought… The most peace-loving and advanced race in the universe,” eventually providing “the ultimate salvation of sentient life.” The details don’t quite all work with the show’s continuity (although Morrison puts a lot of effort into trying, going out of his way to explain and head off some of the possible complications), but its effort to reinvent the series’ mythos goes well beyond anything else the Doctor Who Magazine comic had ever tried, and indeed found itself broadly legitimized in a 2017 episode where Doctor Who off-handedly mentions Marinus as one of the planets on which the Cybermen arose. Although only twenty-four pages long, it’s by some margin the most epic thing Morrison had done to date, eclipsing even the Black Zoid arc in its willingness to rearrange and expand the mythology of its subject matter. It is the first time Morrison arrives like thunder, penning a story that knocks over tables and brashly proclaims itself to be a big deal, doubly so given that it ran concurrently with Zenith Phase I.

It’s a stunningly ambitious story, providing in addition a heroic death for Jamie and a final page reveal that “within five million years, the Cybermen will have evolved again. Beyond the need for bodies. They will become pure thought… The most peace-loving and advanced race in the universe,” eventually providing “the ultimate salvation of sentient life.” The details don’t quite all work with the show’s continuity (although Morrison puts a lot of effort into trying, going out of his way to explain and head off some of the possible complications), but its effort to reinvent the series’ mythos goes well beyond anything else the Doctor Who Magazine comic had ever tried, and indeed found itself broadly legitimized in a 2017 episode where Doctor Who off-handedly mentions Marinus as one of the planets on which the Cybermen arose. Although only twenty-four pages long, it’s by some margin the most epic thing Morrison had done to date, eclipsing even the Black Zoid arc in its willingness to rearrange and expand the mythology of its subject matter. It is the first time Morrison arrives like thunder, penning a story that knocks over tables and brashly proclaims itself to be a big deal, doubly so given that it ran concurrently with Zenith Phase I.

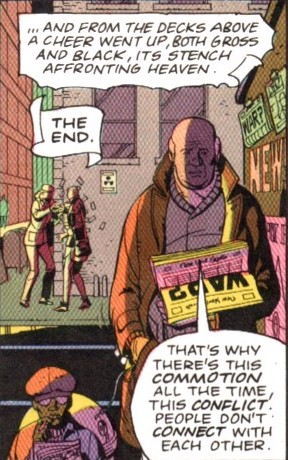

Morrison would pen one more Doctor Who comic in August of 1988, a single-installment piece called “Culture Shock” featuring ex-Ken Campbell Roadshow performer Sylvester McCoy’s version of Doctor Who with art by Bryan Hitch. This is unmistakably a minor work, although Morrison has some fun sketching the culture of a sentient hive mind of bacteria. But by this point, Morrison had hit it big, wrapping his first arc of Animal Man up and commencing with Phase II of Zenith, and throwaway British works such as “Culture Shock” and “Old Scores” (published the same month) were rapidly disappearing from his ouvre.

How had Morrison finally secured this breakthrough? In one sense the answer is easy—he was one of the writers to pitch at Karen Berger’s February 1987 trip to the UK with Dick Giordano. The body of work this could have been secured on the basis of is narrow—his Future Shocks for 2000 AD and Zoids are the two most obvious candidates. One possibility—asserted by Moore, at least—is that he passed Morrison’s name to Berger, although Moore’s recollection of the chronology on this is difficult to reconcile with other evidence even by the standards of Moore’s dubious recollections of linear time. In both of the interviews where Moore discusses this event, he suggests very clearly that he recommended Morrison on the back of Zenith, but that was still six months in the future when Morrison met Berger. It would be tempting, on these grounds, to dismiss the story as Moore cynically attempting to take credit for Morrison’s career, except that Karen Berger has also confirmed that Morrison came to her recommended by Moore, recalling that “I reached out to Alan and I said, ‘Alan, who else do you see out there that’s really talented?’ And he goes, ‘oh, you really should meet this guy Grant Morrison, he’s got something. He’s only done a few things but, you know.’” Between Moore and Berger’s accounts, the recommendation clearly happened, and was surely why Morrison got the meeting, just as Moore’s recommendation explained why Neil Gaiman, who hadn’t even published Violent Cases yet, met with her the same day.

How had Morrison finally secured this breakthrough? In one sense the answer is easy—he was one of the writers to pitch at Karen Berger’s February 1987 trip to the UK with Dick Giordano. The body of work this could have been secured on the basis of is narrow—his Future Shocks for 2000 AD and Zoids are the two most obvious candidates. One possibility—asserted by Moore, at least—is that he passed Morrison’s name to Berger, although Moore’s recollection of the chronology on this is difficult to reconcile with other evidence even by the standards of Moore’s dubious recollections of linear time. In both of the interviews where Moore discusses this event, he suggests very clearly that he recommended Morrison on the back of Zenith, but that was still six months in the future when Morrison met Berger. It would be tempting, on these grounds, to dismiss the story as Moore cynically attempting to take credit for Morrison’s career, except that Karen Berger has also confirmed that Morrison came to her recommended by Moore, recalling that “I reached out to Alan and I said, ‘Alan, who else do you see out there that’s really talented?’ And he goes, ‘oh, you really should meet this guy Grant Morrison, he’s got something. He’s only done a few things but, you know.’” Between Moore and Berger’s accounts, the recommendation clearly happened, and was surely why Morrison got the meeting, just as Moore’s recommendation explained why Neil Gaiman, who hadn’t even published Violent Cases yet, met with her the same day.

The question—one of the most puzzling mysteries of the War—is why. What had Morrison done to impress Moore enough to forward his name along to Karen Berger? Was Moore a surprisingly big Zoids fan? Did one of Morrison’s early Future Shocks catch his eye? Did he have fonder memories of Morrison’s unused Kid Marvelman script than he has let on? None of these feel especially likely, and yet one of them must be true: Morrison simply hadn’t written much else by February of 1987 that could have earned him that kind of recommendation.

Perhaps, then, Morrison’s breakthrough is not best explained through mere causality. The nature of Watchmen was that a rival to Moore had to emerge. And Morrison was the most obviously qualified figure. His mixture of a deep and genuine love for superheroes and a brashly punk sensibility combined to make him a figure who could both be an enfant terrible and a loyal company man. More to the point, he was a magician, devoting his Will to becoming a rock star of comics at the precise moment that Moore’s magic required such a figure to set him against.

Perhaps, then, the reason that Moore recommended Grant Morrison to Karen Berger was simply that he had to, just as Berger had to hire him. There were forces in play far beyond mere choice and decision—vast systems of magic and fate that had to be satisfied. Even if the works with which Morrison would prove himself good enough to do the job lay in the future, he already was good enough. If Moore sits in Eternity, after all, than so must Morrison, always his rival, even before the conditions that made it necessary arose. Moore recommended Morrison because he had always recommended Morrison—because putting his rival in place was simply something that had to happen.

Perhaps, then, the reason that Moore recommended Grant Morrison to Karen Berger was simply that he had to, just as Berger had to hire him. There were forces in play far beyond mere choice and decision—vast systems of magic and fate that had to be satisfied. Even if the works with which Morrison would prove himself good enough to do the job lay in the future, he already was good enough. If Moore sits in Eternity, after all, than so must Morrison, always his rival, even before the conditions that made it necessary arose. Moore recommended Morrison because he had always recommended Morrison—because putting his rival in place was simply something that had to happen.

And with that, they stood opposed to each other. The implacable magus, methodical and grandiose, crafting his vast edifices of meticulous grandeur. And the impertinent warlock, brash and iconoclastic, cutting his path through the world spraying peals of stardust and dazzle. Two men left with no choice but antipathy, no choice but to clash, their visions for the dawning century at inevitable loggerheads. These were the only things either of them could allow themselves to be. This was simply how it was, how it always had to be. Alan Moore and Grant Morrison, the greatest magicians of their age, staring across the psychic landscape of the late 1980s, and realizing their enmity.

And with that, they stood opposed to each other. The implacable magus, methodical and grandiose, crafting his vast edifices of meticulous grandeur. And the impertinent warlock, brash and iconoclastic, cutting his path through the world spraying peals of stardust and dazzle. Two men left with no choice but antipathy, no choice but to clash, their visions for the dawning century at inevitable loggerheads. These were the only things either of them could allow themselves to be. This was simply how it was, how it always had to be. Alan Moore and Grant Morrison, the greatest magicians of their age, staring across the psychic landscape of the late 1980s, and realizing their enmity.

“I must Create a System, or be enslav’d by another Mans

I will not Reason & Compare: my business is to Create” – William Blake, Jerusalem The Emanation of the Giant Albion

{In 1985, David Lloyd, seeing a gap in the comics market that the now defunct Warrior had filled, pitched a new anthology to IPC to be called Fantastic Adventure. His idea was in many ways to follow the classic Pat Mills structure that IPC had not really launched anything new within in some time—take a bunch of concepts recognizable from popular culture and do smart, innovative, and edgy comic takes on them. Lloyd was at the time chairman of the Society of Strip Illustration, and so had an extensive network both of old pros and up and comers who could be tapped. Among these was Grant Morrison, who was in the earliest stages of his music-to-comics transition, and who ended up being the primary creative force within the proposed magazine, penning three of this six strips in its intended initial lineup, with the rest being a Dungeons and Dragons knockoff from Steve Moore and John Ridgway, a James Bond knockoff called Mirror Man, and a futuristic Batman riff called Brother Bones from Jamie Delano and John Higgins that would later become World Without End at DC Comics.

Morrison, meanwhile, was set to handle The California Crew, an A-Team clone featuring a ragtag group of soldiers of fortune in interstellar space, Johnny O’Hara, an Indiana Jones riff, and a less-comedic Ghostbusters to be called Nightwalkers. But Morrison also pitched a fourth idea—a superhero strip based on the idea of a generational history of superheroes, with World War II-era ones fighting for the UK and Germany, a team of government-sponsored ones in the 1960s, and a lone 1980s one who was the child of two of the 1960s one. Morrison’s take was rooted in period pastiches—as he explained it, ”we had characters in the ’40s who were very like the early Superman. We had the Maximan character, who was very primitive. We had the ’60s characters who were very Marvel pop arty. Then we brought it up to date with the realistic ’80s characters.” This superhero strip failed to make it into the Fantastic Adventure dummy, which in turn failed to get approved by IPC, who decided to go with M.A.S.K., a riff on the Kenner-produced toy/TV series that would be cheaper to produce as Kenner would front the startup costs.

Two years later, however, under the editorships of Steve MacManus and Richard Burton, 2000 AD decided to make a bid for renewed relevance by giving a wealth of new talent an opportunity. Applying the time-honored method, they reasoned that their most notable alumn had just had quite a bit of success with a superhero property, and so they would launch one of their own. And with the new policy of giving opportunities to newer talent, Grant Morrison, despite having only spent a year or so penning Future Shocks (compared to Moore’s four year apprenticeship), was given a chance at the strip for the simple reason that he was wildly more enthusiastic about the genre (which, after all, had a meager history in the UK) than anyone else coming up at the time.

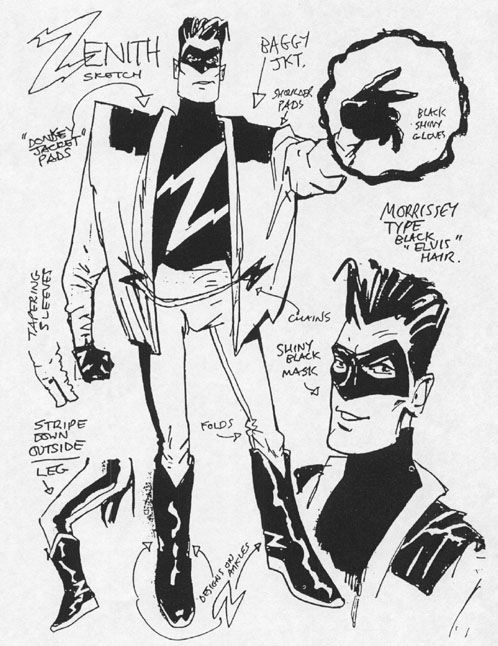

And so Morrison got back to work on his old proposal, which he substantially rethought. Instead of making the 1980s main character a grim and gritty character in the vein of Frank Miller, Morrison decided to make his strip an conscious reaction against that approach to the genre. As he put it, “I wanted to do something a little less self conscious perhaps, or to align myself with a different current of thinking.” To this end, he turned to the work of Brendan McCarthy, an artist who had split his career between short jobs at IPC and other publishers, often working with his friend Brett Ewins or his art school colleague Peter Milligan. In 1984, the trio worked together on three issues of an anthology entitled Strange Days for Eclipse, which contained a running feature entitled Paradax.

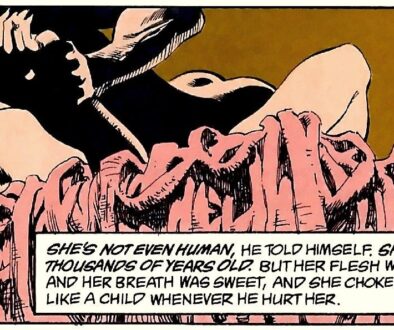

Paradax was in many ways an exemplar of McCarthy’s style—an explosion of color and grotesquery that did not so much embrace punk and psychedelia as seem to burst out of them in some sort of feverish explosion. As Morrison put it, “McCarthy was a styled and prickly genius whose hand had and still has a direct line to his unconscious mind. Imagine that you could take photographs of your dreams, and you will have some idea what McCarthy is able to do with his art.” With Paradax, McCarthy was making his own reaction against Moore, this time against Marvelman, which he accused of being “a continuation of the wordy, purple ‘Don McGregor’ school of writing.” And so he created Paradax, a cab driver who found a magical supersuit that let him walk through walls, and who used this to be a complete and utter asshole. As McCarthy put it, “He would drink, smoke pot, fuck girls, watch himself being interviewed on TV, be an annoying self-infatuated asshole obsessed with stardom, have a manager, and take the money and run.” The result was a raucous and cynical comedy of a strip that skewered the genre conventions of superheroes and looked gorgeous doing it.

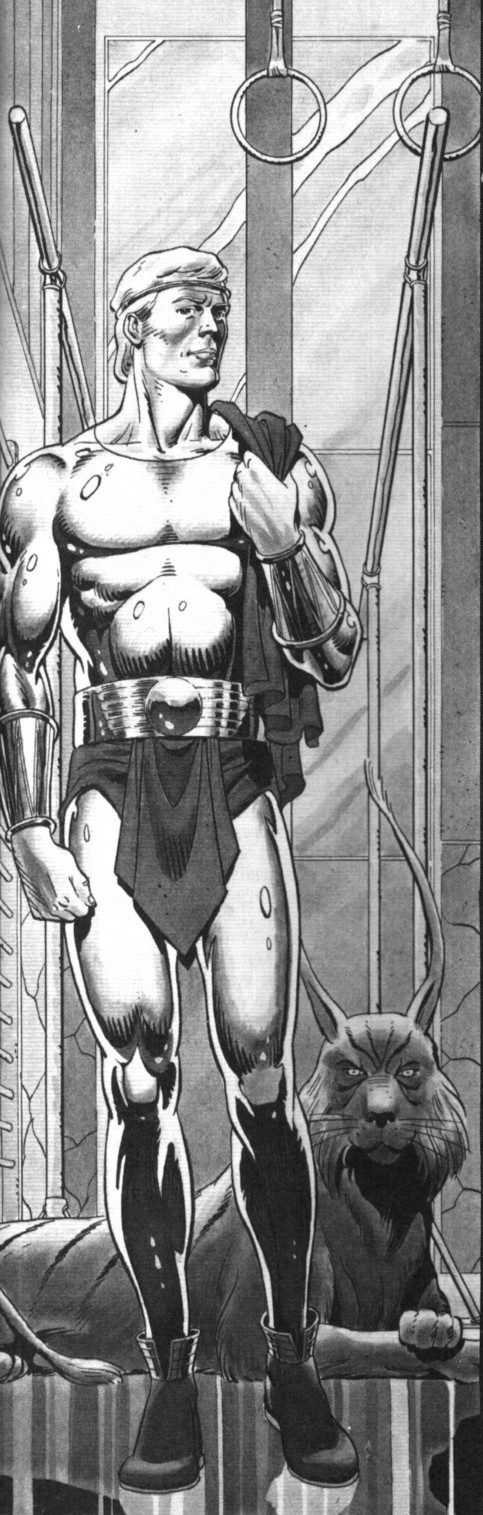

Morrison saw the possibility of a “middle ground between the extremes of Gibbons and Moore’s serious formality and Milligcan-McCarthy’s visionary remixes of modern culture,” combining the detailed alternate universe backstory of Watchmen with a brasher and more emphatically Gen X sensibility that treated superheroes as both very cool and very goofy. His main character, Zenith, was now envisioned as a vapid and amoral mediocrity of a pop star trading on his celebrity status as the sole remaining superhero for chart success. Morrison initially gave the concept to McCarthy, who created a set of design sketches, but declined to draw the book. In Morrison’s telling. “He’d never have done it—the story as it unfolded would have been too ponderous and long-winded for him. I don’t think he ever seriously considered drawing Zenith.”

McCarthy’s take is more complicated. As he puts it, “initially I was quite interested. I designed a bunch of characters from his pitch, but as I read the full scripts later on, I saw that he was lifting quite a lot from Paradax!. The other story elements in Zenith, apart from the Paradax-inspired ‘media superbrat’ stuff seemed like the usual comics fare – ‘super soldiers’ and all that magick/Dr Who stuff he was into. That bored me, as I’d heard it all before… I couldn’t see the upside of illustrating a strip that was essentially ripping off my own original thought, so I passed on drawing it.” This account, made in 2013 as a comment on a Thal Fox article about the copyright situation around Zenith, is blatantly self-serving. While Zenith owes a clear debt to Paradax, this debt exists entirely around the notion of a selfish slacker superhero and in the fact that McCarthy’s designs for the two characters have some broad similarities. The actual plot of Zenith is miles from Paradax, and while it’s certainly riffing on traditional superhero concepts, it’s hardly fair to call it completely derivative, and the attempt has to be taken in the context of McCarthy’s larger later career transition into being an embittered asshole that yells about “the left” and “pc brownshirts”

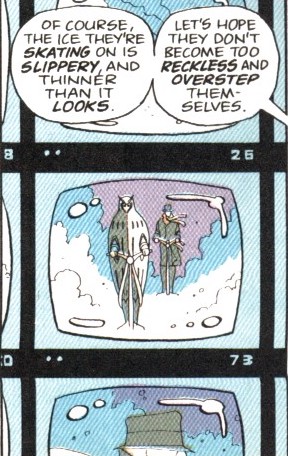

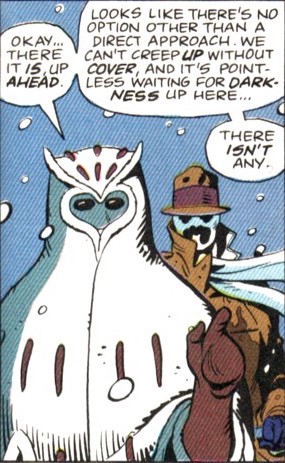

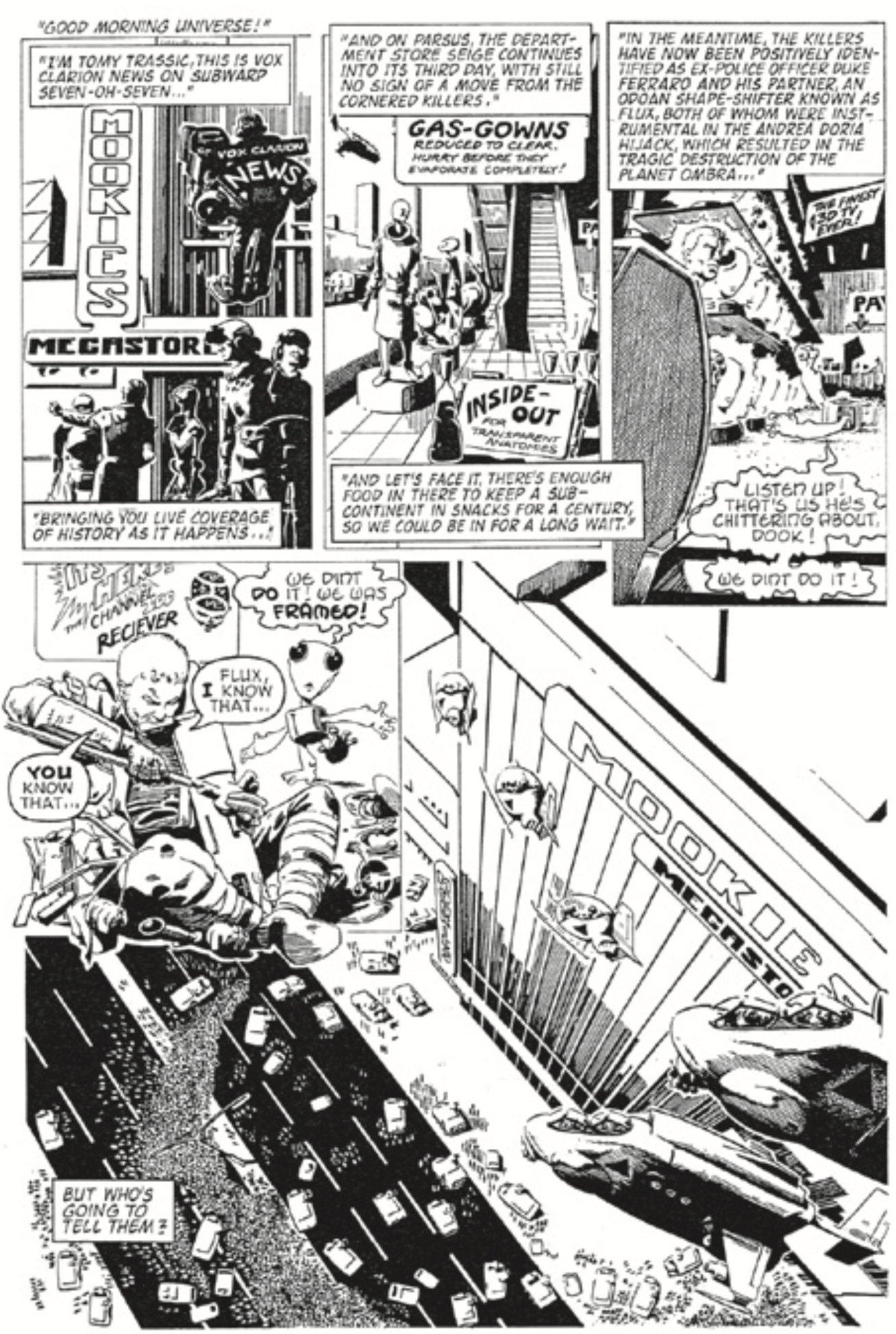

Instead, Morrison turned to Steve Yeowell, with whom he’d already worked on several of his Zoids strips. The resulting serial made its debut in Prog 335 of 2000 AD, two months after the final issue of Watchmen and nine months before Morrison’s US debut with Animal Man. For its first two runs (stylized as Phases), Zenith could fairly be accused of wearing its influences on its sleeve. Phase I in particular makes its debt to Marvelman clear, particularly in its dark and apocalyptic denouement, while Phase II (published in 1988) dive into the secret history of superheroes as government experiments is the same move Moore made in the transition from A Dream of Flying to The Red King Syndrome. And both of these owe a clear debt to Paradax, especially the early installments of each, before the plot really starts up, which allow Morrison to have lots of fun with superhero celebrity culture.

But this framing reveals its own absurdity. All art is the sum of influences, and if Zenith’s are easy to detect, they’re still a remarkable and original set of influences to choose in the first place. Morrison identifies two approaches to superheroes that are diametrically opposed—deliberately so, as McCarthy notes. One is born out of taking their premise very seriously and asking what it would actually be like, the other out of a lacerating satire about exactly what assholes human beings really are and how little superpowers would change that fact. These aren’t just a pair of influences, but two that are diametrically opposed—and that Morrison finds a way to synthesize into a single approach. To claim it as derivative, as both McCarthy and Moore (who describes it as “a bit of a cross between Captain Britain and Marvelman,” a description that suggests Moore had read more of the strip than he let on, since the Captain Britain riff really doesn’t begin until Phase III in 1989/90) do is profoundly misleading, obscuring the fact that Morrison is building something genuinely new out of the parts he’s chosen.

And there are significant components of Zenith that are intensely original. The villains, for instance—extradimensional horrors called the Lloigor and known as “the Many Angled Ones,” are a Lovecraft riff with no obvious precedents in Moore or McCarthy. They’re still not entirely original ideas, of course, but they exist within the long tradition of writers treating the Cthulhu mythos as a shared setting. (Indeed, the name “Lloigor” emerged out of that tradition, first appearing in August Derleth and Mark Schorer’s 1932 story “The Lair of the Star Spawn” and later used by British writer Colin Wilson in a story called “The Return of the Lloigor” published in the seminal 1969 anthology Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos.) The idea as Morrison uses it—extradimensional horrors that can only manifest in the universe by possessing the body of a superhuman (as ordinary humans are too weak to contain them) is an effective note of horror that adds depths to the comic that do not have any roots in its superhero-based sources.

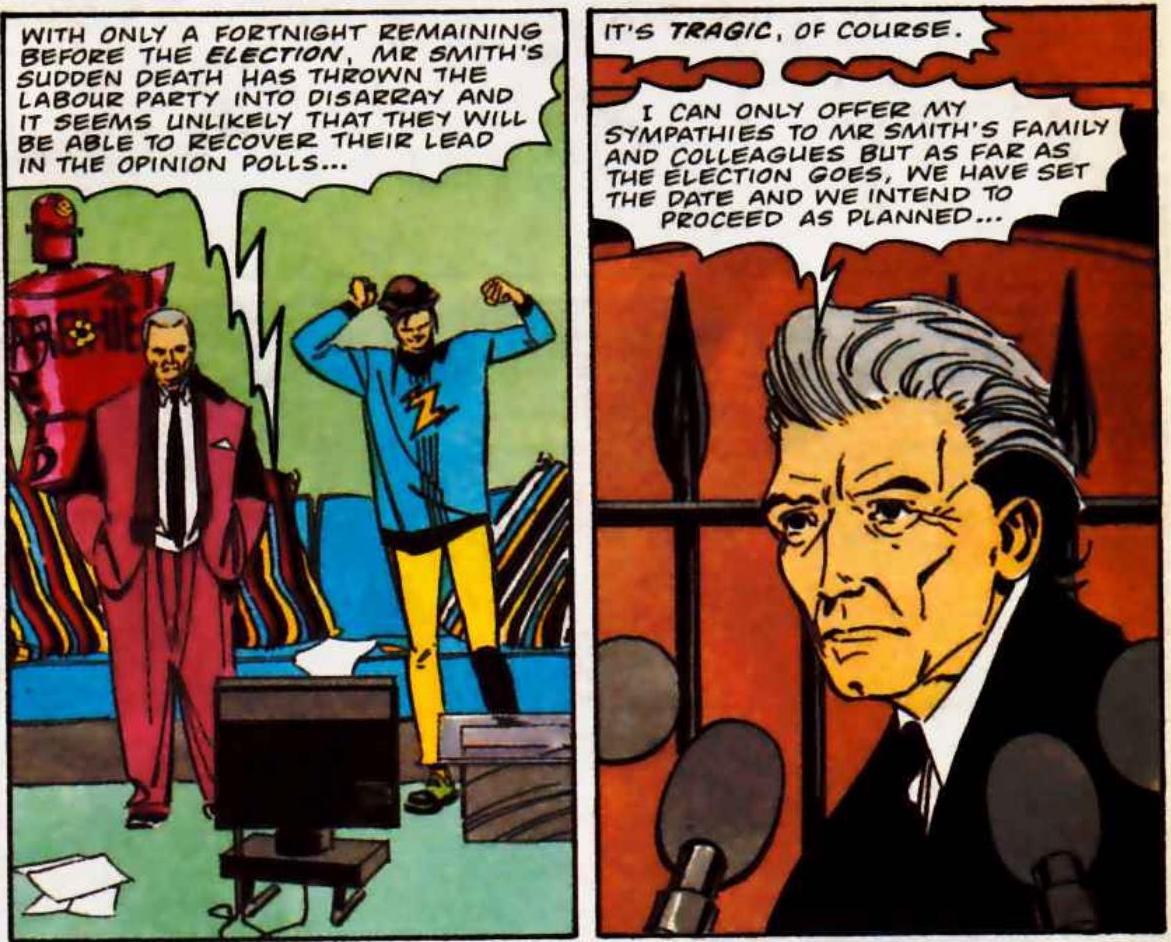

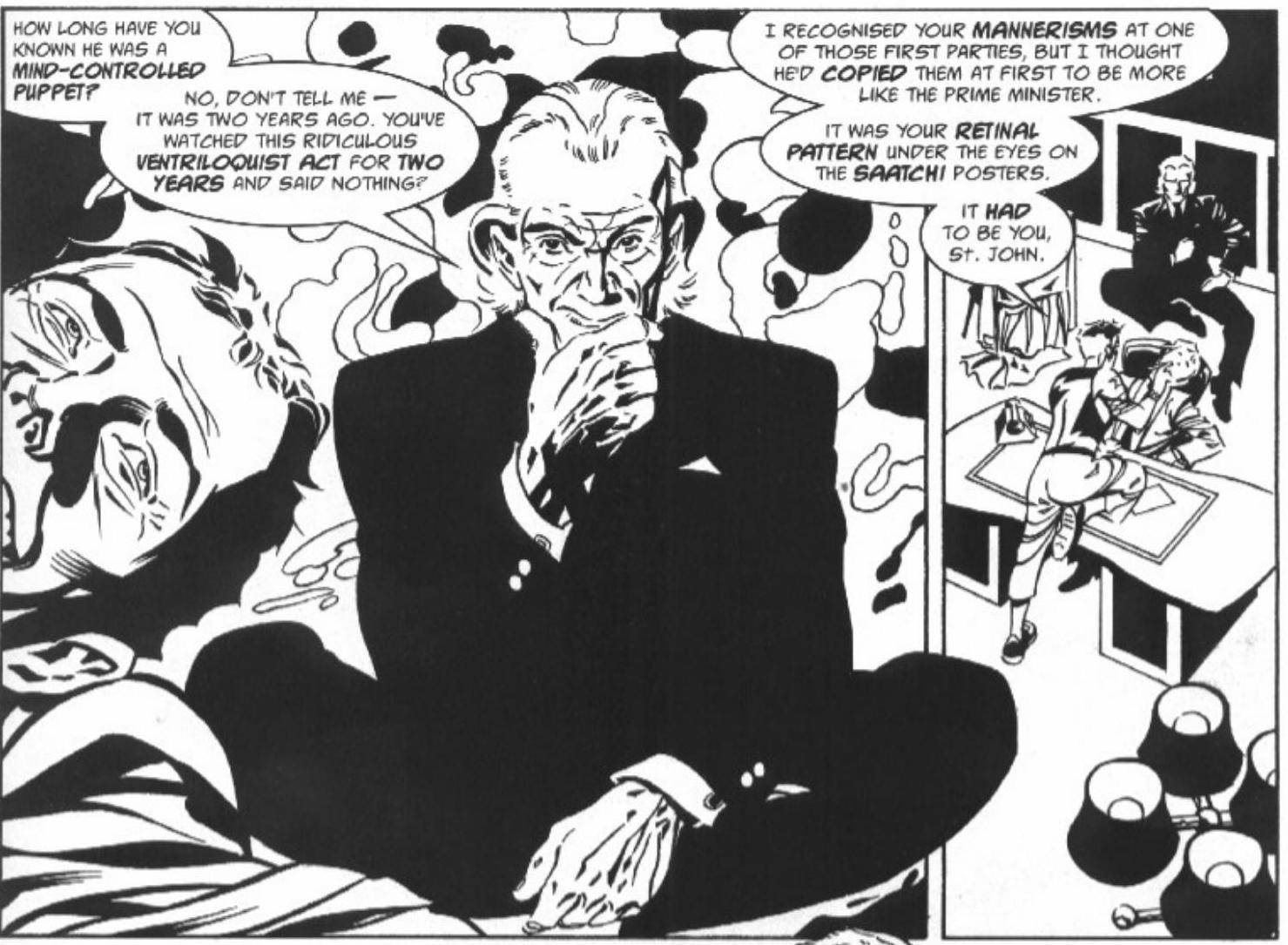

Perhaps the most bracingly original element of Zenith, however, is Peter St. John, a powerful telepath who in the 1960s was the hippy superhero Mandala, but by 1987 has become a Tory MP. The underlying sentiment—that the idealistic youth of the 1960s had by the 1980s sold out and elected a bunch of conservatives into power—was common enough by this point, but Morrison’s spin on it is uniquely barbed, with the character being particularly loathsome, most obviously when he only participates in the final battle against the Lloigor-possessed Nazi supervillain Masterman (the twin of the World War II-era Masterman) to aid his reelection campaign, a sly and grimly funny parallel to the fame-obsessed Zenith. It’s a bitter satire of Thatcher’s own cynical electioneering via the Falklands War, and of the media’s complicity with conservative politics—a genuinely, properly brilliant idea that Morrison executes with deft acuity.

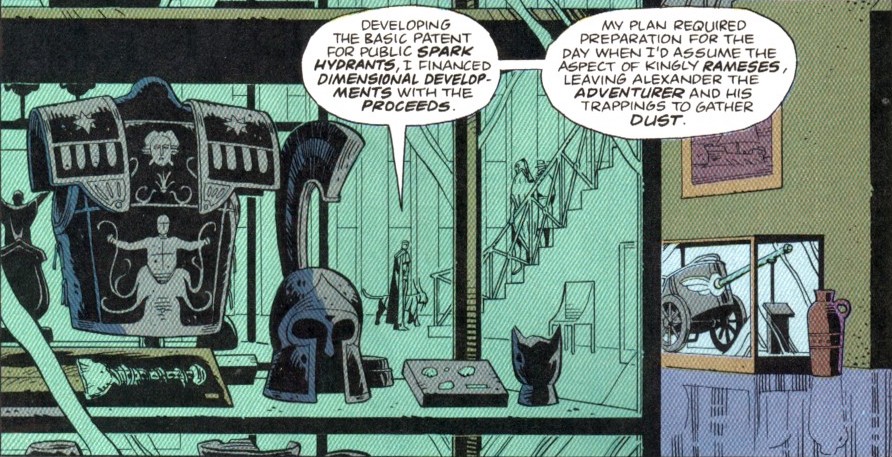

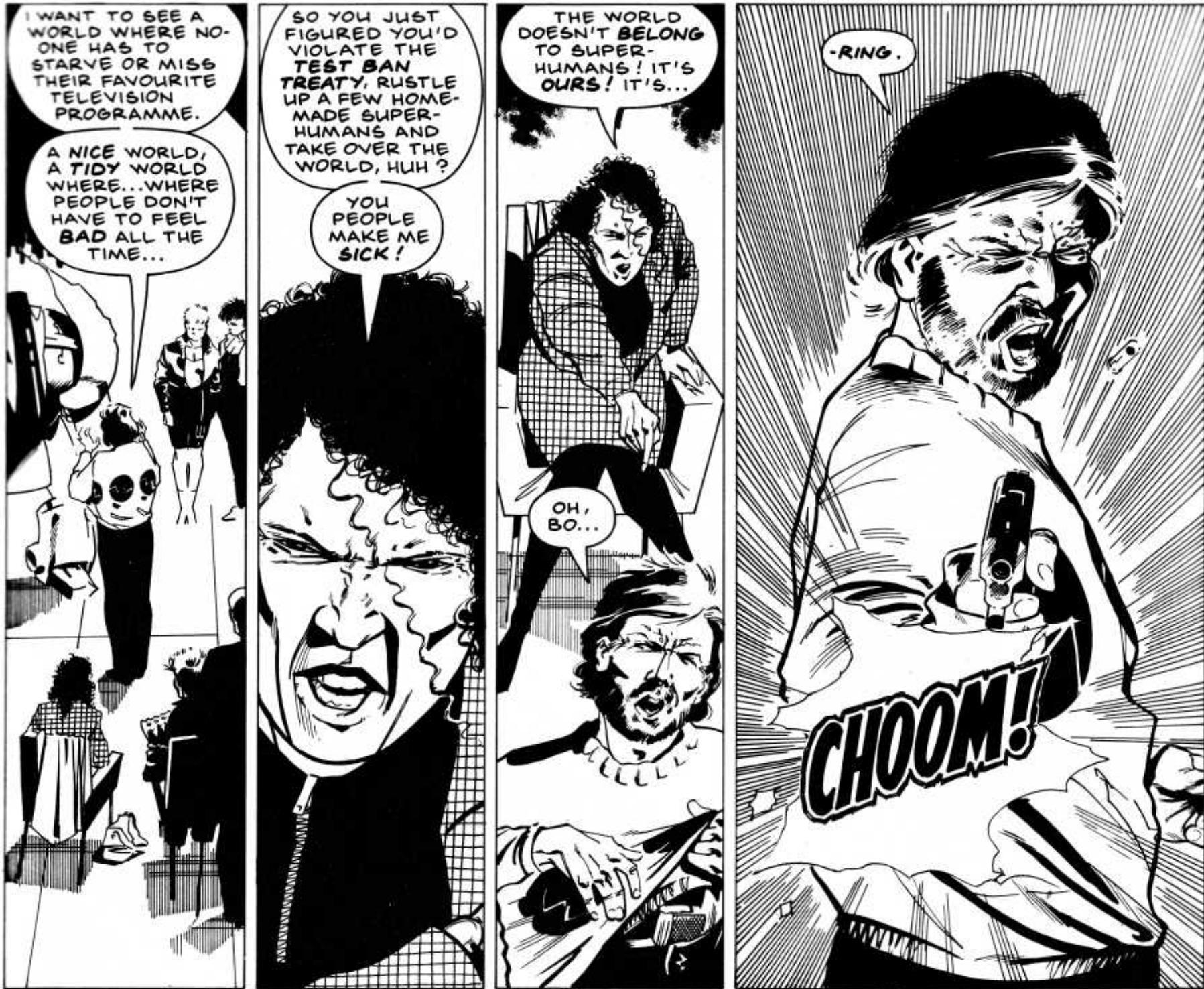

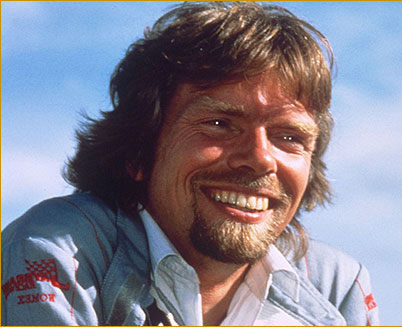

With Phase II, Morrison and Yeowell began to move more decisively beyond their influences. Yeowell redesigned the title character, replacing his McCarthy-designed costume with a studded leather jacket, while Morrison began to cut loose. As mentioned, his plot still owed a clear debt to Marvelman, making the same Act II move towards exploring the character’s origin story. But the vehicle Morrison chooses to do that via—a Richard Branson pastiche named Scott Wallace who plans to nuke London on the grounds that “I’m just sick of the way the world’s going and I think I could do a better job, build a better world. That’s all. I want to see a world where no one has to starve or miss their favorite television programme. A nice world. A tidy world where… where people don’t have to feel bad all the time.” (Shortly after this monologue, he guns down a CIA agent for “being such a moan.”)

All of this fit into Morrison’s stated goals for the project, creating a world of superheroes that was resolutely consumerist. Branson had begun his career as a record store owner, expanding this in 1972 to a record label, initially breaking out with Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells, and later signing the Sex Pistols after they’d been fired from two previous record labels. In the 1980s, however, he largely became the smiling and photogenic face of Margaret Thatcher’s drive towards privatization, establishing an airline business off the back of the government;’s decision to end British Airways’ monopoly over the US-UK route. (Musing on Thatcher, Branson noted, “”On social matters, she was not necessarily my cup of tea, but she realised that you can’t deal with social problems if the economic side is not working. Getting the economy going was the first step to getting the social side sorted.”) So Morrison was picking a particularly astute target for what he was doing with Zenith, in many ways setting up a solid counterweight to Peter St. John (who was by this point Defense Secretary), who ultimately stops him by telepathically manipulating him to abort the launch after Zenith distracts him by pointing out how much of a bother it will be ruling the world.

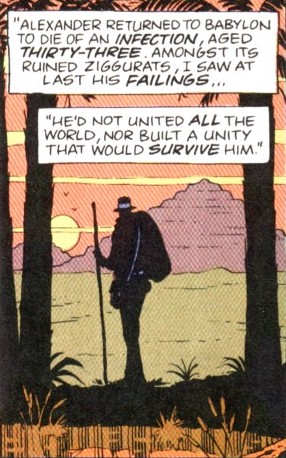

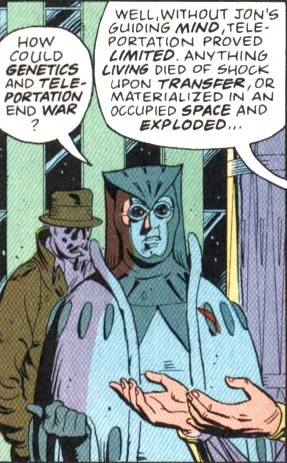

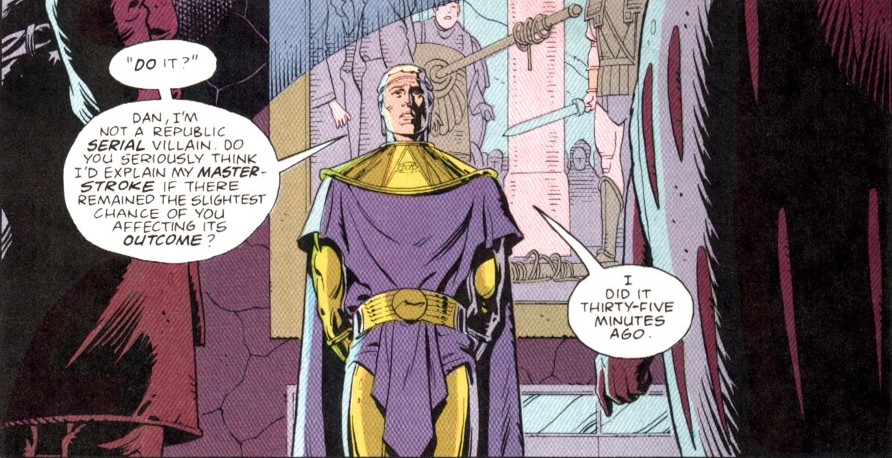

More to the point, however, Morrison is clearly taking aim at Watchmen here—Wallace’s scheme to take over the world by staging a nuclear attack on a major city has obvious similarities to Ozymandias’s, and Morrison even has Wallace compare himself to Alexander the Great to hammer the point home. But instead of being a horrifying yet effective plan by the smartest man in the world, it’s the scheme of an obviously deluded madman who talks about wanting to be “a nice sort of Hitler” and fretting about how nobody likes him. It’s a biting parody, giving voice to Morrison’s criticism that “in order for Watchmen’s plot to ring true, we were required to entertain the belief that the world’s smartest man would do the world’s stupidest thing after thinking about it all his life. It’s there where Watchmen’s rigorous logic gives out, where its irony is drawn so tight that the bowstring gives. Its road ends. As the apotheosis of the relevant, realistic superhero stories, it had come face-to-face with the bursting walls of its own fictional bubble, its fundamental lack of likelihood.” And in fairness, it has to be said that Morrison’s imagined apocalypse of idiot child capitalist entrepreneurs has come far closer to realism than anything in Watchmen itself.

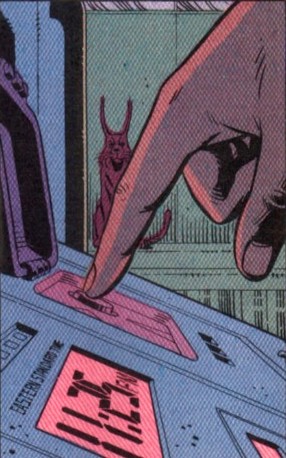

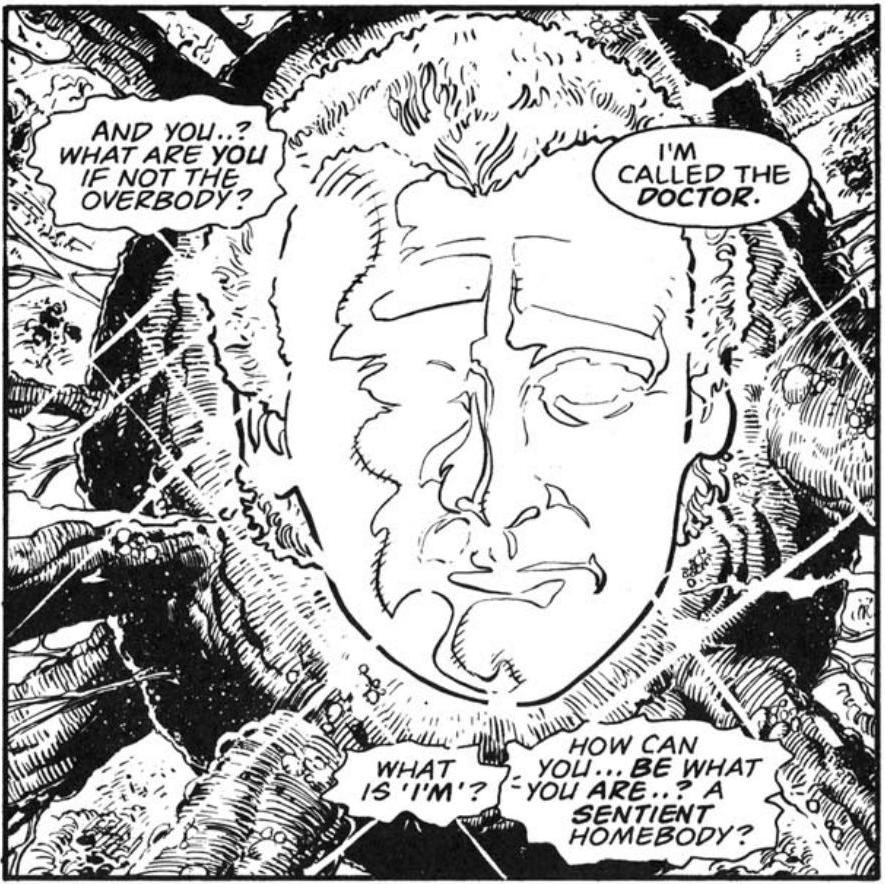

Phase II also saw Morrison introducing Chimera, one of the superhuman children bred to create the 1960s generation of heroes. Initially appearing in an interlude between Phases I and II, Chimera is described as having “rose up in a storm of shapes, speaking in tongues.” Initially trapped inside an electromagnetic field, Chimera is freed when Zenith damages the equipment containing them during a fight with Warhead, the cybernetically animated remains of his own father, and confronts Zenith at the end of the Phase, appearing to him as a multifaceted explosion of images quoting William Blake’s The Book of Urizen, a rare instance of anybody in the War actually bothering to read Blake’s prophetic works, then decides to take the form of a crystalline pyramid with an entire universe inside. As with the Lloigor, it’s a concept of startling weirdness, extravagant in its sheer size as a concept. It exemplifies what would become Morrison’s trademark approach, as distinctive and iconic as Moore’s formalism or poetic cadence—comics constructed not out of the meticulous deployment and exploration of ideas, but out of the sheer excess of them—an overwhelming and decadent flood of ideas.

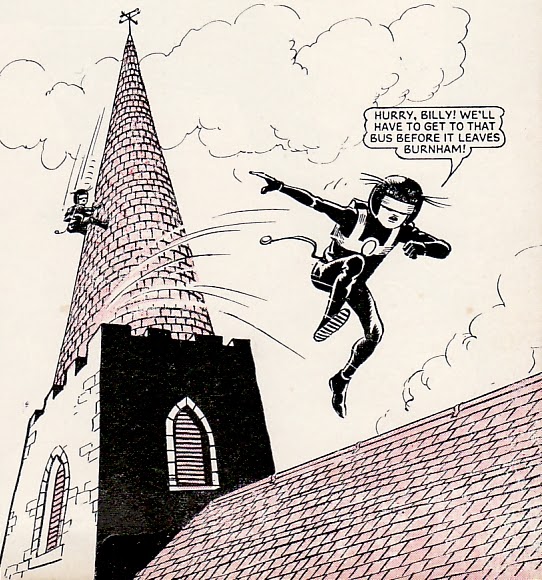

This approach only intensified in Phase III, for which Morrison introduced an elaborate multiverse concept, then had the Lloigor attacking realities in an attempt to take over the entirety of creation. Within this setup he conducts a Crisis on Infinite Earths pastiche, with an alternate version of World War II-era British superhero Maximan playing the role of the Monitor. Told over twenty-five parts, it is the longest Zenith story and, more to the point, the most aggressively high concept. Morrison employs the multiverse not just to introduce alternate versions of existing characters such as Mantra, the anarchist Alternative 88 counterpart to Peter St. John, or Vertex, the heroic and virtuous counterpart of Zenith from Alternative 300, but to bring in the entire history of British superhero comics. Many of the characters were used directly, but where he couldn’t Morrison made near-mixx analogues, so, for instance, the Beano characters Billy the Cat and Katie become Tiger Tom and Katie, while Starr of Wonderland, who appeared for a few years in D.C. Thompson’s 1960s Diana, became Miss Wonderstar.

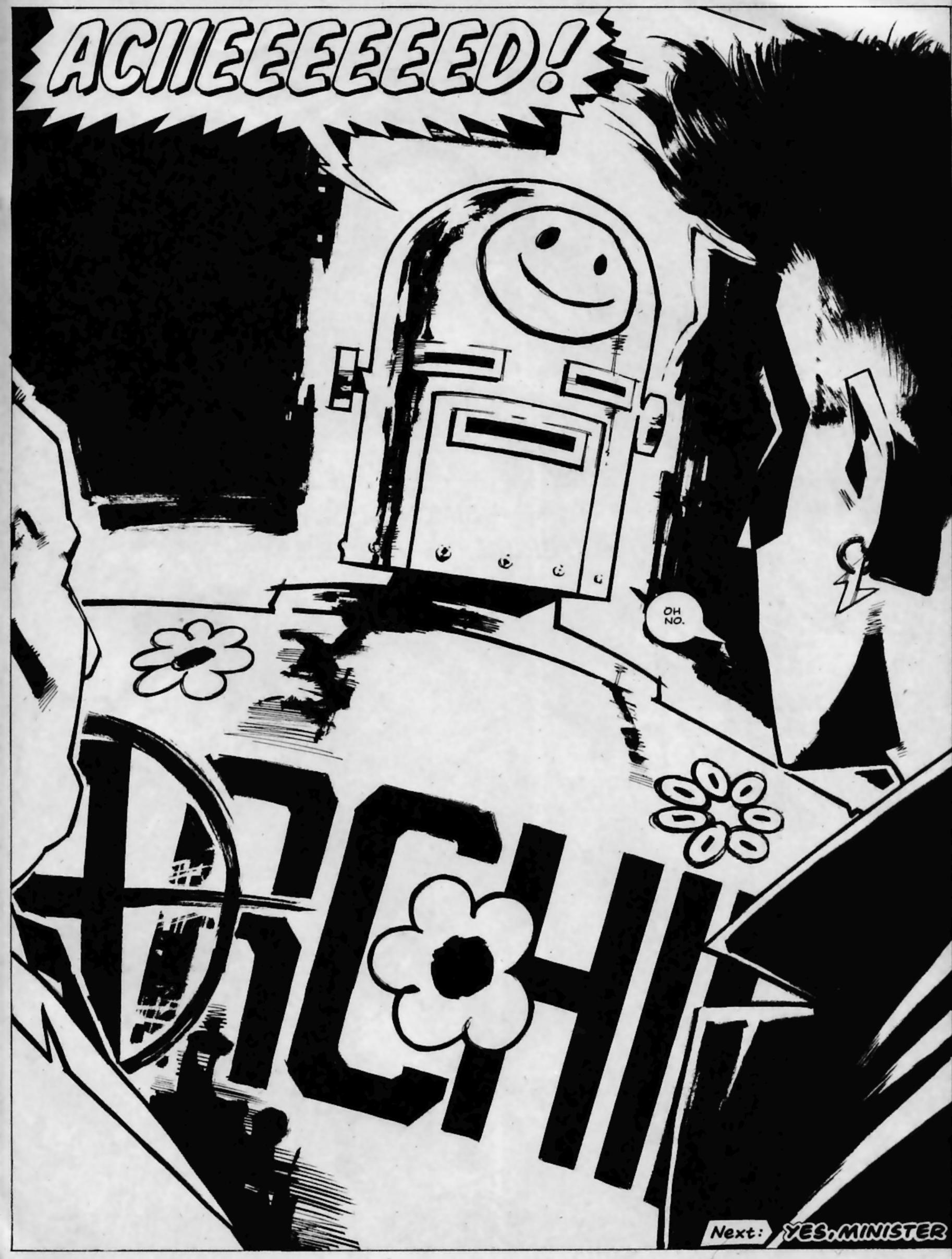

But elsewhere, particularly with titles published by IPC, Morrison was able to use the real things, and so the storyline becomes a cavalcade of classic British comics characters: the Steel Claw, Leopard, Black Archer, Cat Girl, Tri-Man, Thunderbolt Jackson, Ace Hart, and, most famously, Robot Archie, the classic heroic robot from the 1950s Lion comic (IPC’s answer to Eagle), who Morrison brought back as an acid house fan who appears at Zenith’s door, decked out in flower and smiley face stickers, screaming “ACIIEEEEEED!” While a few of these, like Steel Claw and Robot Archie, are at least somewhat well known, the bulk are obscurities and deep cuts (to date nobody has actually managed to identify everyone Morrison and Yeowell throw in) that Morrison is pillaging with an enthusiastic thoroughness that would not be seen again until Moore used a similar approach in League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Morrison once again has a mocking finger pointed at Alan Moore, this time taking his approach to Marvelman, not just bringing a single obscure superhero into the present day but dozens of them, all in a chaotic motley that Morrison laughingly called “one of the greatest superhero crossover events ever; they all just argue and fuck up constantly.”

Phase III, however, also provides a glimpse of what would become one of Morrison’s primary failure modes. In his dizzying blitz of concepts and impudent provocation he can too often fall into the trap of transgression for its own sake. Towards the end of Phase III, Morrison does a joke reveal that one of the heroes, Meta Maid, is transgender, playing the reveal as a trans panic joke based around repeatedly misgendering her and stressing that “it’s all just makeup and hormone treatments. [S]he’s saving up for the op.” It’s gross, transphobic, and, given Morrison’s grinning description of Zenith’s “supermen, superwomen, and supertrannies” in 2011, something he remains depressingly unrepentant about.

The most unfortunate consequence of this tendency within Morrison’s career also intersected with Zenith in the 2000 AD Winter Special for 1990, where his protege Mark Millar did a text story under the banner Zenith: Tales of the Alternative Earths. Millar was at this point at the absolute dawn of his career, having written a pair of Future Shocks along with a satirical “second coming of Christ” book called Saviour for the short-lived Trident Comics, and his fleeting contribution to Zenith marked the first but by no means last time he would get an early career boost from his fellow Glaswegian, whom he met when he interviewed him for Fantasy Advertiser at the beginning of 1989. Millar’s story is not itself objectionable—he follows in the basic pattern of Morrison’s Zenith, this time taking aim at Moore’s third Miracleman arc and the beginnings of Neil Gaiman’s run, depicting a world in which superheroes have taken over and built a utopia, eliminating all but one human, the narrator, a man named Arthur Montgomery. The piece does not display what would eventually become Millar’s worst instincts, and is indeed largely unobjectionable, if also unremarkable. But knowledge of who Millar would become puts an unsettling pall over the work. It opens with a lengthy oration in which Montgomery establishes himself as a resolutely small-minded Little Englander who complains about everything and responds to the sudden disappearance of the rest of humanity by saying, “’Blinkin’ LABOUR council.’ Bleedin;’ papers were right about them. ‘Blinkin’ Labour Council.’” In his loneliness as the last human he resolves to kill himself, but is saved by the superheroes, who bring his dead wife back to life to keep him company and (it’s implied through the unreliable narration) manipulate his mind to ensure he’s happier. Its cynicism is cold, clinical, and misanthropic, a spine of cold ugliness animating its basic technical competence; comparisons to the Lloigor are tempting.

By the time Phase III of Zenith had been published, meanwhile, Morrison, as he put it, “rich” off the back of Arkham Asylum, which netted him a royalty on an order of magnitude with few comparisons beyond Watchmen itself. By the time he returned for Phase IV two years later, as Morrison put it, “I’d moved on and was more excited by the possibilities of working with American superheroes,. By 1992, Zenith seemed like something dragged up from my past.” By this point 2000 AD itself was radically changed as well, running as a full color magazine since Prog 723, just three weeks after the end of Phase III.

With Phase IV, Morrison takes up what would become one of his classic themes: the “evil wins” outcome, in which he depicts at length a world in which the villains win and impose a horrifying dystopian order upon the world. In it, the Lloigor possess all remaining members of the 1960s generation save for Peter St. John, and commence a systematic take over of the world in a frame narration by the 1940s superhero creator Michael Peyne via his unpublished book Seizing the Fire. For sixteen installments of Lovecraftian V for Vendetta pastiche, Morrison wheeled out his bag of tricks one last time, producing a work that in his view transcends the influence-bound Phase I. And he’s not wrong. For all that Morrison’s influences are never far away, the latter Phases of Zenith crackle with a confident excess, the work of someone who has figured out a style and is now thrilling to push at the edges of it, figuring out the full scope of what’s possible within it.