Chapter Nine: The Private Tongue (The Darkness of Mere Being)

And what of Moore? Where was he as the company he forsook remade itself in what they imagined his image to be? How did the Prophet of Eternity respond to what he had wrought?

And what of Moore? Where was he as the company he forsook remade itself in what they imagined his image to be? How did the Prophet of Eternity respond to what he had wrought?

At first, retreat. As he told an interviewer around the time he was finishing the script for Watchmen #12, “I’m going to take a couple of months off and basically not have a single creative thought in my head for that entire period.” This was both unsurprising and necessary. By this point it would have been clear to him that Watchmen was going to leave him in a vastly changed financial situation (he suggested in 1991 that it had” made me hundreds of thousands of pounds” though noted “that’s not a fraction of what DC made out of it”). On top of that, he was understandably tired. Since his career had taken off in earnest in 1981, he’d been working at a staggering clip across multiple publishers. V for Vendetta, Miracleman, Watchmen, Swamp Thing, The Ballad of Halo Jones, The Killing Joke, and Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow had essentially all come in a five year frenzy of productivity with few analogues in the history of British art or literature.

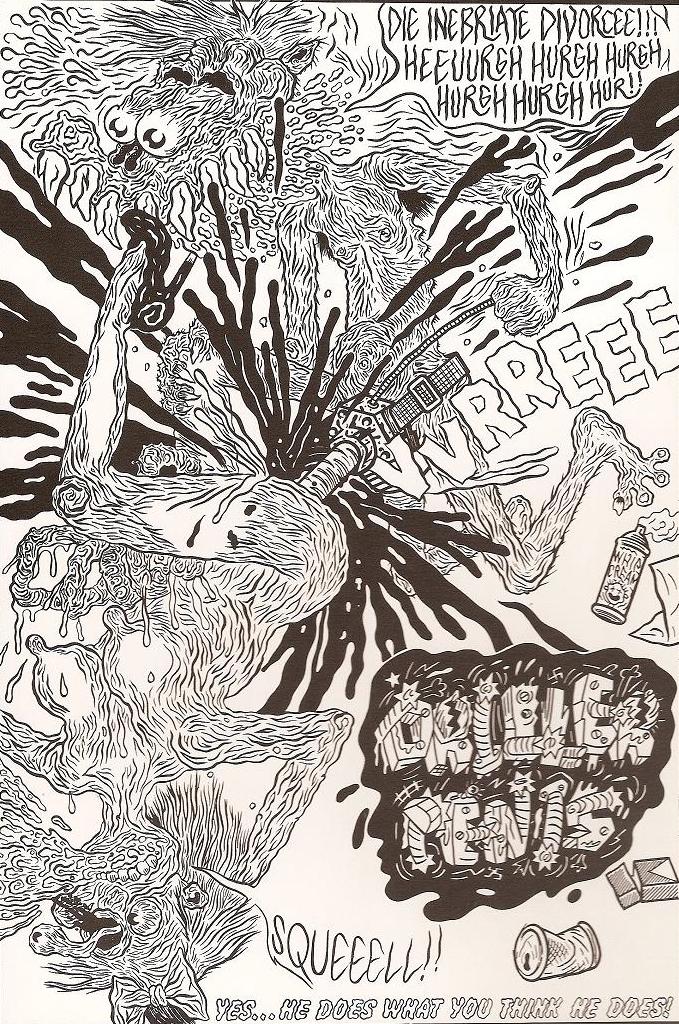

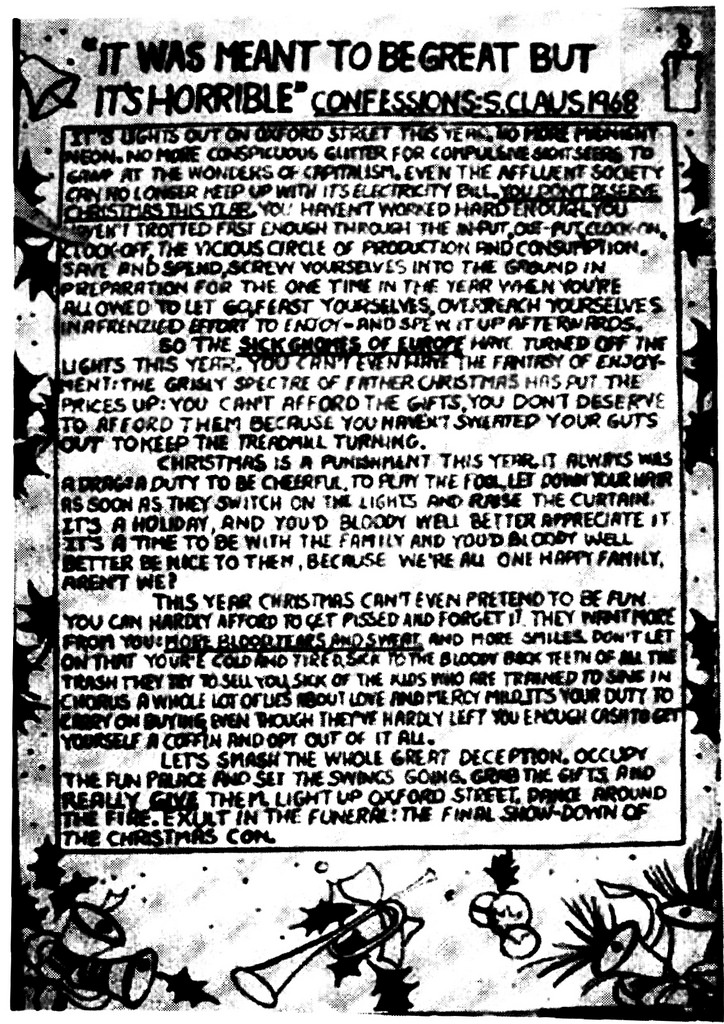

As he filtered back towards productivity, he began by completing his stray obligations to DC: writing the final book of V for Vendetta, and some UK promotional work for Watchmen, including the UK Comic Arts Convention in September, which would prove to be his last comics convention for decades after he found himself unable to move around for all the people mobbing him. And he closed out the decade working on a series of minor projects, many of them seemingly informed by little more than personal whimsy. In 1989, for instance, he dusted off his old Curt Vile pseudonym to indulge his longstanding love of the underground comix tradition of R. Crumb and S. Clay Wilson via a collaboration with Savage Pencil, with whom he’d formerly shared the comics page of Sounds. The result, published in a magazine called Corpsemeat Comix, is an eight-page gross-out epic in which what broadly appears to be a fire-breathing dragon takes up making his own pornography after discovering a new law forbids him from purchasing. The result, which gives the comic its memorable title, is “Driller Penis: Yes… He Does What You Think He Does.” And indeed, he does.

In a similar vein, he wrote a pair of stories for Knockabout Comics, a UK publisher of underground comics for which he’d previously written the autobiographical text piece “Brasso with Rosie,” also with art by Savage Pencil, for their 1984 Knockabout Trial Special, a benefit book for their defense against one of the obscenity trials they were frequently embroiled in. The first of these appeared in Outrageous Tales of the Old Testament, a deliberate provocation intended to show that the Christian morality under which they were prosecuted was full of stuff just as obscene as their usual offerings. Moore contributed an adaptation of Leviticus 20 with art by Hunt Emerson in which Moses’s proclamation of the laws surrounding sexuality cause the listeners to rip each other to pieces for perceived violations of this law. The second, a contribution to the Seven Deadly Sins volume, sees him pair with Mike Matthews for “Lust,” a narration of the Cold War as a sexual affair in which climax is nuclear war. (Punchline: “Afterwards, for a very long time, we just lay there silently, side by side, smoking.”)

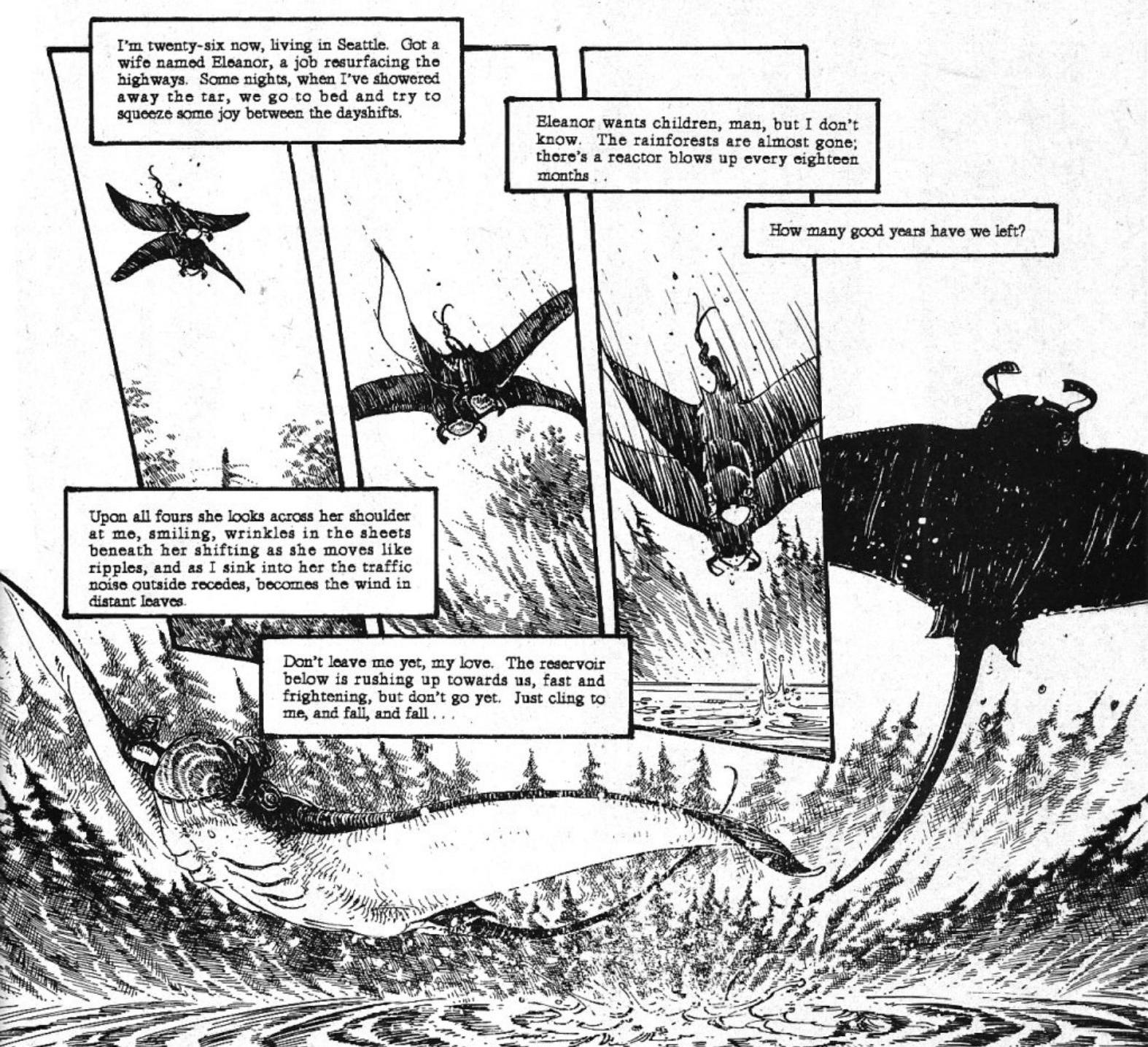

Elsewhere in the period he penned “Act of Faith,” a four page backup feature for Stephen Murphy and Michael Zulli’s indie classic The Puma Blues. This comic offered a dreamlike account of a game warden in a futuristic Massachusetts taking care of the often strange and mutated animals in a Massachusetts forest. Moore’s story takes the form of a brief narration by a man recalling adolescent masturbation while watching flying manta rays mate, which they do in a freefall, plummeting towards the acidic and poisoned water they evolved out of. (“Her rippled white; her underside revealed in maddening glimpses to the male behind, scarred where she forced an eagle from its nest last year, to raise her young. My cock lept with her lashing tail, as if attached by fishing line.”)

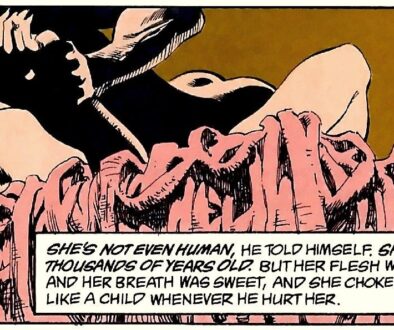

Moore also began to branch out beyond comics and try his hand at other media. He had, to be sure, written prose before, including some early text stories for the UK Superman Annual and Batman Annual in 1984, and a variety of essays, but in 1987 he contributed the story “A Hypothetical Lizard” to the third volume of Emma Bull and Will Shetterly’s Liavek shared world. This setting, which tells the stories of magician’s wield luck magic in the eponymous trade city of Liavek. Moore’s story tells of the workers at the House Without Clocks, magical sex workers such as “Khafi, a nineteen-year-old dislocationist who, lying upon his stomach, could curl his body backward until the buttocks were seated comfortably upon the top of his head while his face smiled out from behind the ankles. There was Delice, a woman in middle age who used fourteen needles to provoke inconceivable pleasures and torments, all without leaving the faintest mark. Mopetel, suspending her own heartbeat and breath, could approximate a corpse-like state for more than two hours.” The story’s viewpoint character is Som-Som, who has had the two hemispheres of her brain severed and a porcelain mask affixed over the right side of her head so that only her left eye and ear can hear, meaning that everything she learns will be forever trapped in the right side of her brain, away from the speech centers. The story is a tale of moody horror that does not quite come together (it is, to be fair, his first real experiment in long-form prose storytelling), but that flares into brilliance with casual ease throughout its length.

It will not escape observation that these stories all relate to sex in some fashion. This is certainly not true of everything he wrote in the period—he also did Brought to Light in the period, for instance, and wrote a seven-page story for Gary Leach’s new A1 anthology (later issues of which would feature his second run of Bojeffries Saga stories) in which they revisited the Warpsmiths characters from their early Marvelman work. Nevertheless, sex clearly formed a major component of Moore’s thought in this period. This connects sensibly enough to both his earlier and later work—consider “Rite of Spring” and “A Brother To Dragons” for DC, and his soon to commence Lost Girls project with Melinda Gebbie.

It will not escape observation that these stories all relate to sex in some fashion. This is certainly not true of everything he wrote in the period—he also did Brought to Light in the period, for instance, and wrote a seven-page story for Gary Leach’s new A1 anthology (later issues of which would feature his second run of Bojeffries Saga stories) in which they revisited the Warpsmiths characters from their early Marvelman work. Nevertheless, sex clearly formed a major component of Moore’s thought in this period. This connects sensibly enough to both his earlier and later work—consider “Rite of Spring” and “A Brother To Dragons” for DC, and his soon to commence Lost Girls project with Melinda Gebbie.

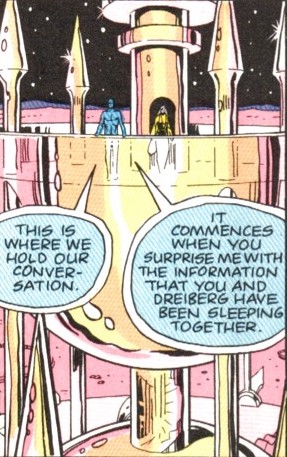

Nevertheless, without being unduly Freudian about it, there are reasons why this theme would have stood out to Moore in these specific years. During this period, Moore’s marriage to Phyllis expanded into a polyamorous triad. As Moore explains it, “There was me, there was my wife, and there was our girlfriend, and we were all living together quite openly in a different sort of relationship… We decided we wanted to experiment with a different way of living.. We did this very openly; we didn’t hide it.” Living in an unusual romantic situation such as this it is easy, without any prurience, to see how questions of sexual expression might interest Moore. This did not manifest in any sort of trying to tell the same tale over and over again—there are few similarities between “A Hypothetical Lizard” and “Driller Penis: Yes… He Does What You Think He Does” besides their author and their interest in sex. But it is clear that the nature of human desire and intimacy was large in Moore’s mind as he navigated his unusual relationship.

(1).jpg)

The girlfriend alluded to by Moore was a woman named Deborah Delano. Born in the summer of 1958, Delano was the fourth of four children, born after her mother went into premature labor upon seeing the badly broken arm of Delano’s older brother. (“Oooer, it were bent back like a banana,” Delano recalls her mother narrating the incident.) She grew up on the King’s Heath council estate, about three miles south-west of Moore’s beloved Spring Boroughs. (It was where his grandmother was forcibly relocated when the Boroughs were cleared out for development in 1970, and where she subsequently died three months later.) The estate had won an award for its construction the lesser part of a decade earlier, its incorporation of green spaces and a “village center” design praised as the model of future design in Britain (“which, unluckily, it proved to be,” Moore notes wryly in Voice of the Fire, referring to its eventual collapse along with the rest of the working class neighborhoods). Delano recalls “a butcher who made filthy jokes and gestures with sausages and slabs of liver for a receptive audience of housewives; a grocery store, where local news of illegitimate births, shotgun weddings and domestic beatings could be exchanged; a bakery, with its array of Eccles cakes, coconut Madeleines and individual fresh cream trifles served by a very dainty class of woman who forswore gossip of any kind; a post office, where people posted parcels to their more glamorous émigré relatives in Australia; a hairdresser who, it later transpired, was a closeted lesbian; and a hardware store with that smell now lost forever.”

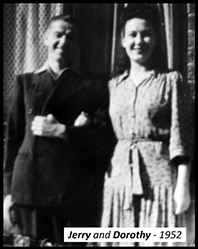

Comparisons with her future boyfriend are inevitable. Where he described a happy childhood, Delano’s was far more complicated. Her mother was a sexually adventurous woman—in 1937, at the age of fifteen, she’d paid her way down to London with sexual favors, while in 1940 she had a broken engagement with an soldier who disappeared a few weeks before their wedding with £10,000 of the army’s money. In 1941, she got pregnant, and with her mother’s deft intervention she married one of the possible fathers, a Scottish soldier named Jerry Gibbons. They were married in a brief and unceremonious service in the town hall, and went to the cinema to see How Green Was My Valley afterwards. Three days later, Jerry was deployed to Northern Africa.

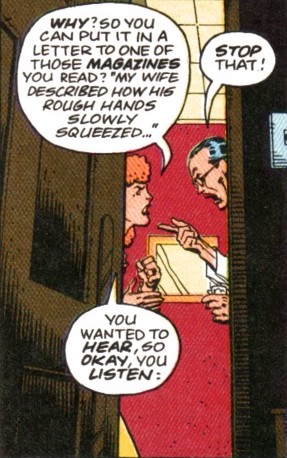

Upon his return, Dorothy’s parents offered to watch her daughter so they could enjoy their first evening together in four years. When Dorothy asked what he might want to do, however, his response was, as attested by Delano, “Ah’m awae fer a drink wi’ mah pals. Ye can fuck off an’ earn some money, I’ll meet ye beack here at hof pas’ eleven.” Upon his return (in reality at midnight), he proceeded to abuse her for not engaging in sex work. In practice, Dorothy skirted the edge of this designation—Delano describes her maintaining a stable of relationships with men who would offer her “gifts” of grocery money, which Jerry would promptly snatch up, giving his wife only a few pounds a week.

Unsurprisingly, Jerry was physically and verbally abusive to both his wife and children. Delano recounts that “he didn’t hit her often but when he did, it was to mark the end of their dialogue, a full stop to an outrageous sentence. Violence was Jerry’s dominant emotional response. He never beat her up. It was always a single punch and a black eye. This happened, probably, six times during my childhood.” In one particularly harrowing incident, Delano recounts Jerry coming home to find his middle daughter sitting at the kitchen table with her boyfriend. Several hours later, after the boyfriend had gone home, Jerry burst into his daughter’s room, threw a suitcase at her, and then violently dragged her out of bed demanding that she leave the house.

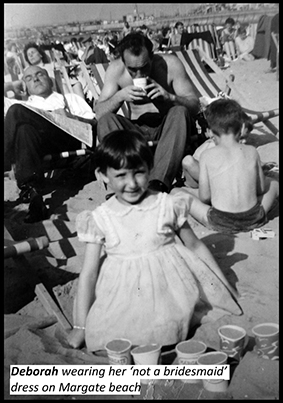

This is, of course, not to say that there weren’t happy memories. Delano recounts childhood trips to the beach in Margate during the factory fortnight (the two-week period at the end of July/beginning of August when manufacturing shut down across the country to allow workers to vacation with their schoolchildren), and, with more perversity, her mother’s fondness for true crime narratives. Indeed, Delano devotes several pages of her memoir to this subject, talking about hours spent offering Jack the Ripper theories, the brutally unjust execution of Edith Thompson, and her mother’s favorite, the “burning car murderer” Alfred Arthur Rouse, whose tale would later be recounted by Moore in the penultimate chapter of Voice of the Fire.

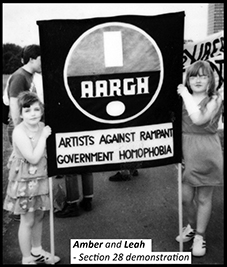

Delano’s childhood was further complicated by her sexuality. As she tells it, “when people ask me when I first knew I was a lesbian I’m never sure what to say. We are trapped in symbol and language, sot he answer would have to be that it was not until after I knew such a category existed. But I knew I loved women, and I knew I had sexual responses to other girls from the age of four.” She recounts a childhood sexual relationship with another girl on the Spencer estates (which she’d moved to as a young child) marked by trysts “in her garden shed, in the thicket of the trees near the bus stop and on the wasteland before they built the center for the disabled,” although as she grew older “the general ‘wrongness’ of our relationship had marred its simple delight.” Many years later, she recalls seeing her later while “walking hand-in-hand with my girlfriend and her two children” (this is almost certainly Phyllis, Leah, and Amber) and saying hello, only to be confronted by her palpable homophobia.

In the painfully familiar manner of queer adolescents, Delano attempted to cure her evident homosexuality, becoming sexually active at fourteen. She stresses that this was not “sensibly thought through as a plan of action to ‘prove’ my heterosexuality. Everything I did was an emotional train crash—a horrible M25 pile up of neediness, confusion, fear and destruction. I eventually walked away from the smouldering wreckage, but there were some casualties along the way.” She recalls trying LSD for the first time with a hippy friend Mark, and attempting to sleep with him only to be stopped when Mark noted, “you’re not here, with your mind,” and crying in response with the knowledge “that I could go on having sex with men but I was never going to be there.” Shortly before her eighteenth birthday, she confided her attraction to her doctor; he tried to cop a feel, and after she rejected him, had her institutionalized for a week.

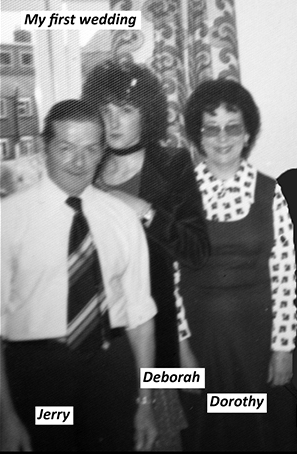

Turning eighteen, Delano became involved in radical leftist politics and moved out of the house following a bitter argument with Jerry (by now revealed as not actually being her biological father) following some typically racist remarks, which culminated in him hurling a flower pot at her as she slept. (“He was a creature of limited imagination when it came to alienating his daughters,” she notes with typical deadpan.) Not long after, she married her boyfriend of four years, more or less on a lark. Like her parents’ wedding thirty-six years earlier, it was a small and efficient civil affair followed by an impromptu party at the house Delano was living in with seven other people. Delano, still working through her sexuality, took to drugs, particularly amphetamines, keeping boyfriends on the side “who just happened to be dealers.”

In 1979, Delano attempted to come out to her husband. He concluded that she was actually just unhappy that she hadn’t been able to go on to her A levels, and offered to fund her going back to school. Delano had been an idiosyncratic student growing up, but found college altogether more satisfying, particularly thriving in her English classes. Eventually she came out to her sister in law, an open witch named Jackie who arranged to take her to The Princess Royal, the local gay pub. She went home with a woman, with whom her husband discovered her the next morning and promptly threw her out.

Having lost her husband’s support she had also to leave school and seek employment. She got an office job and a new place to live, and commenced throwing herself into the local lesbian scene. She made friends at work with a woman named Wendy, who she began dating and eventually moved in with. Eventually, having decided that she was for the first time properly in love, she decided it was time to tell her parents. Her mother’s reaction would eventually provide the title of her memoir: “oo, ere Deb. The things you do.”

Having lost her husband’s support she had also to leave school and seek employment. She got an office job and a new place to live, and commenced throwing herself into the local lesbian scene. She made friends at work with a woman named Wendy, who she began dating and eventually moved in with. Eventually, having decided that she was for the first time properly in love, she decided it was time to tell her parents. Her mother’s reaction would eventually provide the title of her memoir: “oo, ere Deb. The things you do.”

Does this story matter within the larger War? In one sense, perhaps not. Delano never tries to weave a spell to reshape the very fabric of reality to her liking. She does not try to reinvent the world anew. She is an ordinary woman who lives an ordinary life that, for a few admittedly key years in the development of the War, happened to intersect the life of one of its major combatants. She did not alter its course in any definable way—at best one minor, albeit beloved Alan Moore work can be said to exist largely because she did. In a world of vast and quantum uncertainties one can never say with confidence “everything would have gone exactly the same had she never existed“—had she overdosed and died during her period furiously suppressing knowledge of her sexuality with amphetamines, as she freely admits seemed the most likely outcome, noting that “if anyone had been taking bets, I reckon the clever money would’ve been on ‘junkie whore and dead before thirty.’” Perhaps they would have, and Moore would have written the same books with the same impact, almost every word in exactly the same place. Perhaps not. Either way, there is little to point at and called her impact.

Does this story matter within the larger War? In one sense, perhaps not. Delano never tries to weave a spell to reshape the very fabric of reality to her liking. She does not try to reinvent the world anew. She is an ordinary woman who lives an ordinary life that, for a few admittedly key years in the development of the War, happened to intersect the life of one of its major combatants. She did not alter its course in any definable way—at best one minor, albeit beloved Alan Moore work can be said to exist largely because she did. In a world of vast and quantum uncertainties one can never say with confidence “everything would have gone exactly the same had she never existed“—had she overdosed and died during her period furiously suppressing knowledge of her sexuality with amphetamines, as she freely admits seemed the most likely outcome, noting that “if anyone had been taking bets, I reckon the clever money would’ve been on ‘junkie whore and dead before thirty.’” Perhaps they would have, and Moore would have written the same books with the same impact, almost every word in exactly the same place. Perhaps not. Either way, there is little to point at and called her impact.

But it is a poor understanding of the War that treats it as existing entirely in the realm of its combatants and their plots and plans. Yes, Alan Moore and Grant Morrison stand atop the dying days of the 20th century, giants battling to define the world to come. And yes, their lives and the lives of those other men who were pulled into their feud are the easier things to document, their every move and scribbling an object of fascination, another repetition of the War’s fractal geometry. Any thorough telling will focus on these things. But Wars have consequences. There are civilians who get swept up into their narratives, and who come out the other side just as transformed as the protagonists, if not moreso. Without their presence and their witness, it would not be a War; just the bickering of arrogant men.

Delano was introduced to Moore through her girlfriend, Wendy, who was a friend of his and Phyllis’s. Delano recalls her talking about them at work (Wendy was helping them by buying baby clothes for the newborn Leah) and making vague plans to introduce her. The circumstances of this would ultimately be less than happy. The man Wendy left for Delano had grown jealous and increasingly dangerous, and still held a key to their flat, leading Moore to eventually insist that his friend and her new girlfriend pack a few things and come stay with him and Phyllis for a bit. This was in 1980, when Moore was at the earliest dawning of his career, penning backup features for Doctor Who Weekly and Future Shocks for 2000 AD in between writing and drawing Roscoe Moscow and The Stars My Degradation for Sounds and Maxwell the Magic Cat for the Northants Post.

Delano and Wendy settled into a new flat, lost their jobs for being lesbians, and so, as Delano puts it, “signed on the dole and spent the winter in love.” Towards the end of the winter, in February of 1981, Alan Moore came by in the middle of the night and commenced throwing his gloves at the window. (“This is the kind of thing people did before phones became a part of the human anatomy,” Delano notes.) Phyllis had just gone into labor, and Wendy and Delano were needed to watch Leah while they went to the hospital. Moore dropped back by a few hours later to announce, “it’s a girl and she’s called Amber.”

Delano remained extremely close with the Moores, recalling how their home “was a centre for Norhampton’s hipsters. Would-be artists, musicians, feminists and radical intellectuals hung out there,” a single-handed recreation of the Arts Lab culture out of which Moore had originated. After a disastrous and ultimately non-paying summer gig at a camp-shop on the Isle of Wight, she and Wendy moved into a room together in a house previously occupied by the Moores—one Delano recalls having known was haunted because “Phyllis had been awakened one night by Alan sitting up in bed saying ‘Please leave’ to the ether. He could see a little Victorian girl in the middle of the room who simply faded away,” which is presumably one of his first visionary experiences. Delano took a series of jobs: video shop, bar work, and a job driving a laundry van, including a pickup at Althorpe House, where Prince Charles and his new bride Diana Spencer stayed. It was in this period that she decided to change her name, dropping her ex-husband’s surname and, instead of returning to the name of her abusive father, sticking a pin in at atlas and hitting a town of 16,000 in southern California named Delano, a name she also offered to future Hellblazer writer Jamie, her friend through Moore, and the guy who comforted her after her breakup with Wendy.

In 1984, her mother was diagnosed with terminal cancer while Delano was away on holiday in Greece, and died eighteen months later. Around this time, Phyllis got her involved in local Green Party politics. The two joined the local party in 1985 and began spurring it to more action, beginning a series of benefit gigs, for which Alan Moore did the posters, hand-coloring them along with Leah and Amber. Delano recalls one, for a band called Big, which Moore illustrated “with a huge fat man literally tearing his heart out. We coloured the heart and blood that dripped from it in indelible red pen. It gave us no end of pleasure that the red heart adorned the nooks and crannies of Northampton for years after the posters had been ripped down.”

As mentioned, it is unclear exactly when in all of this Delano’s relationship with the Moores evolved into a polyamorous romantic one, nor even what the terms of that were. All three parties have remained largely silent about it—Delano declines to discuss it in much detail in her memoir, except to note that she was effectively parenting Leah and Amber, while Moore describes it simply as “sort of an experimental relationship, I suppose you’d call it,” which is perhaps overstressing the novelty of polyamory. Moore’s account of it as lasting “for two or three years” suggests that it began somewhere in the 1986-87 period, which is to say in that energetic haze of Green Party activism and the publishing of Watchmen.

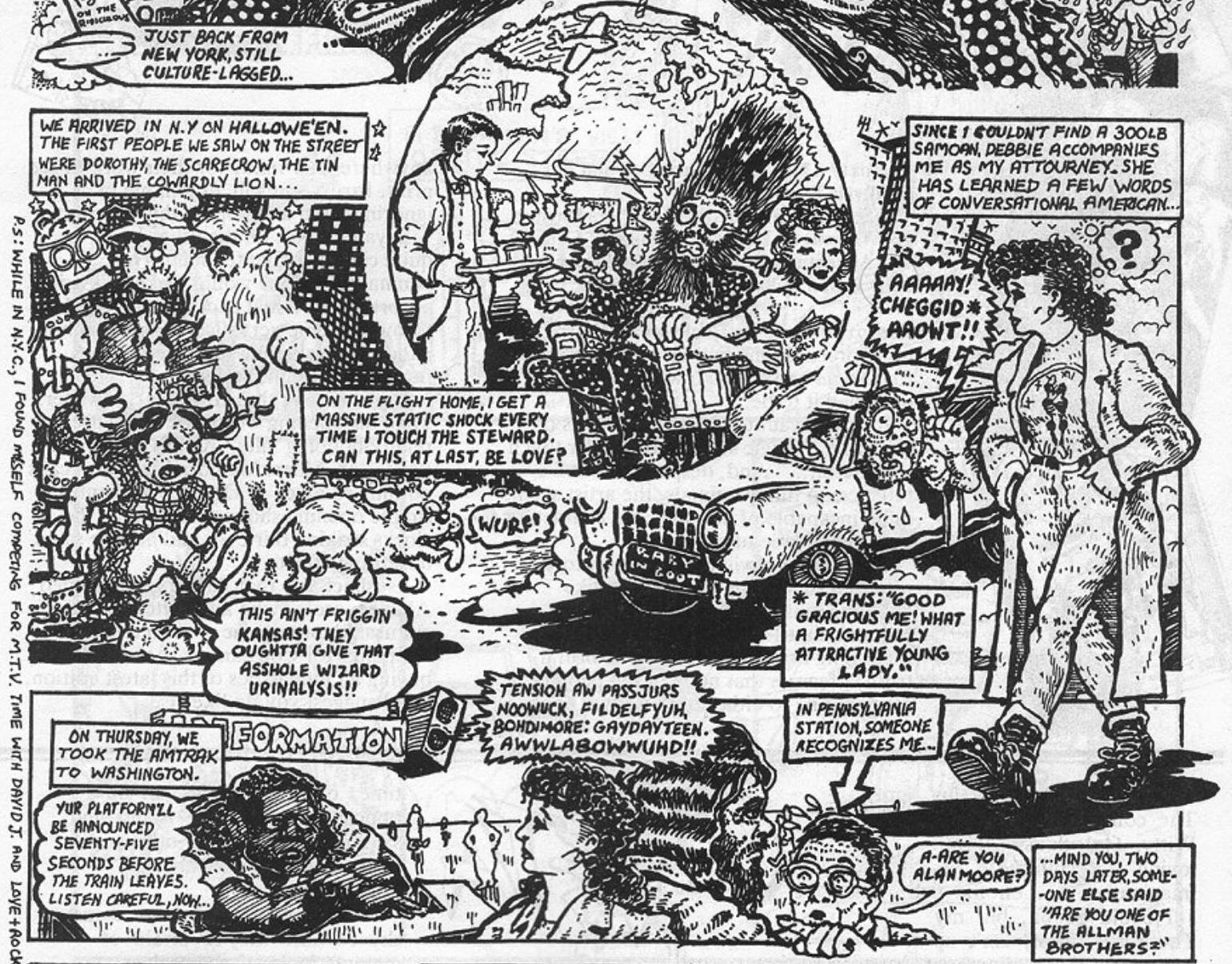

In October of 1987, Delano traveled with Moore for his last trip to the United States, a visit to the Christic Institute in preparation for what would become Brought to Light. Moore drew a one-page strip for Heartbreak Hotel entitled “A Letter From Northampton” humorously recounting the trip, and claiming that Delano accompanied him “since I couldn’t find a 300lb Samoan” in an homage to Hunter S. Thompson’s account of Oscar Acosta in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. (Acosta was in fact Chicano.) That same month, in her speech at the Conservative Party Conference, Margaret Thatcher included a line in her speech decrying how “Children who need to be taught to respect traditional moral values are being taught that they have an inalienable right to be gay.” Two months later, a Tory MP introduced an amendment to the pending Local Government Bill addressing the supposed issue. This amendment would become known as Clause 28.

Clause 28, more properly known as Section 28, proclaimed that local authorities were not to “intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality” or to “promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship.” The language was intentionally broad, designed to create a chilling effect—one oft-quoted comment made by Malcolm Sinclair, the 20th Earl of Caithness, noted that the target of Clause 28 was “the whole gamut of homosexuality, homosexual acts, homosexual relationships, even the abstract concept.”

This bill did not, of course, occur without a larger context. Back in 1967, Harold Wilson’s Labour government passed the Sexual Offenses Act 1967, which reversed the centuries-old prohibition on same sex relationships between consenting adults, although it established a higher age of consent than for heterosexual relations. (On the other hand, anal sex between heterosexual couples remained illegal until 1994, so it would be a mistake to treat this as some sort of coherent expression of sexual morals.) Following the rise of AIDS in the early 1980s, however, attitudes began to shift and homophobia became more rampant—in 1983, just after the disease was finally renamed from GRID or Gay-Related Immune Deficiency, 62% of the British population believed same-sex relationships to generally be wrong. By 1987, this had risen to 75%, and the Conservatives’ general election campaign began to run on the issue, attacking the Labour party with claims that it was teaching homosexuality in schools, while others such as Bill Brownhill, the leader of the South Staffordshire Council in Wolverhampton, proclaimed that “as a cure I would put 90% of queers in the ruddy gas chambers,” while Manchester Chief Constable described AIDS victims as “swirling around in a cesspit of their own making,” a viewpoint Thatcher publicly applauded.

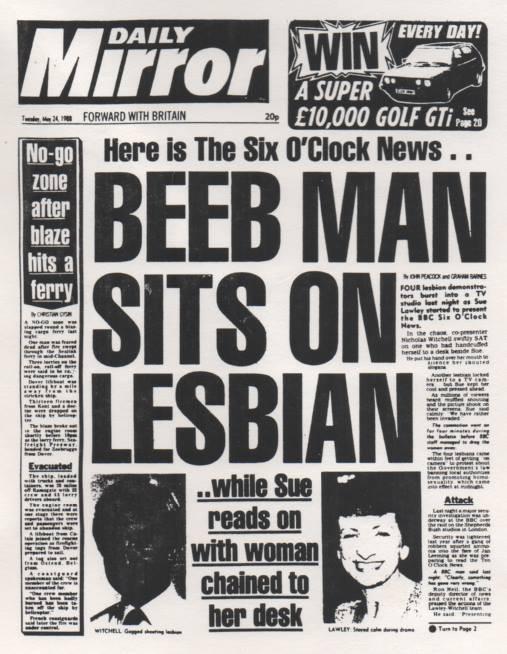

But since the Stonewall riots in the US in 1969, the gay community had begun organizing politically, a process that accelerated as the AIDS crisis ripped through it, creating an urgent need for public health measures. And in the face of such a brazenly hateful effort at suppression, this organization intensified. On February 20, 1988, organizers in Manchester staged a march that attracted 20,000 people, and after the bill’s passage through Parliament in March (with Labour, in what would be their standard strategy under Neil Kinnock, meekly supporting it to avoid being accused of radicalism) more than 30,000 attended a protest in London. Perhaps most memorably, On May 23rd, the day before the law took effect, a group of activists broke into the newsroom during transmission of the Six O’Clock News and disrupted the broadcast, with one of them successfully handcuffing herself to presenter Sue Lawley’s desk, while another was tackled by presenter Nicholas Witchell, leading to the infamous Daily Mirror headline “Beeb Man Sits on Lesbian.” These efforts all ultimately failed, and Clause 28 would remain law until 2003, but they provided the foundation for the larger gay rights movement in the UK.

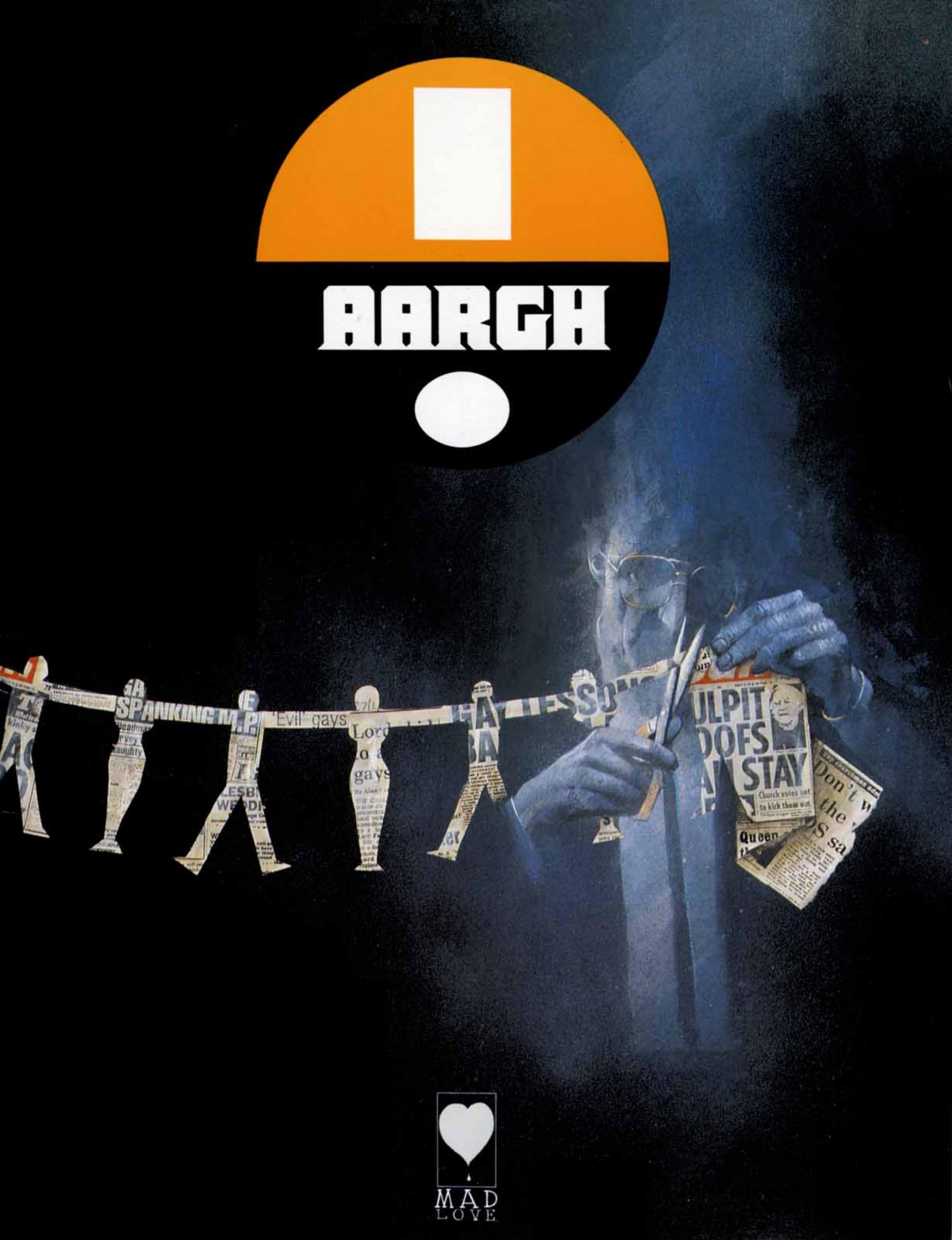

For Moore, Clause 28 was deeply chilling development. “It seemed that both my immediate family and a lot of our friends were being menaced.” Certainly the law was aimed more or less directly at people like them; as Delano puts it, “I was in fact ‘pretending’ to be a parent to Leah and Amber,” recounting how teachers at Amber’s school forbade her from attending parents’ evening. And it’s clear Moore was profoundly disturbed by the development; writing in March, the month the law passed through Parliament, Moore noted, “my youngest daughter is seven and the tabloid press are circulating the idea of concentration camps for persons with AIDS. The new riot police wear black visors, as do their horses, and their vans have rotating video cameras mounted on top. The government has expressed a desire to eradicate homosexuality, even as an abstract concept, and one can only speculate as to which minority will be the next legislated against. I’m thinking of taking my family and getting out of this country soon, sometime voer the next couple of years. It’s cold and it’s mean spirited and I don’t like it here anymore.” Instead of this departure, however, Moore, along with his partners, began organizing a benefit book for organizations protesting the legislation. Moore had by this time become friends with Dave Sim, the Canadian outsider comics artist who self-published his acclaimed comic Cerebus the Aardvark through his own company Aardvark-Vanaheim, and was broadly interested in self-publishing his own work. Sim encouraged him to make the benefit book his first project, and Moore, who reasoned that “we can’t see anyone else publishing it,” accepted his offer to guarantee the printing costs. The result, released in October of 1988 under the imprint Mad Love (with a logo designed by Sim), was AARGH!, or Artists Against Rampant Government Homophobia.

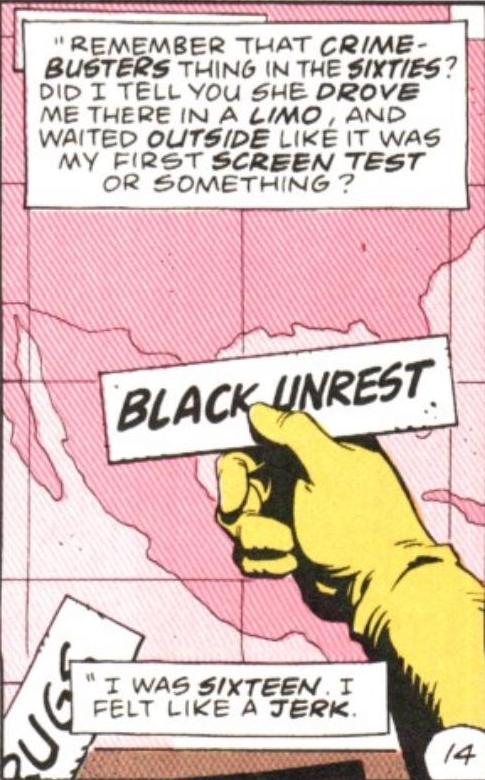

AARGH! is a strange book, defined in most regards by a fundamental disjunct between its nominal purpose and the people who made it. To be effective it had to sell, and its chief selling point was that It was spearheaded by the guy who wrote Watchmen, Batman: The Killing Joke, and V for Vendetta. Accordingly, Moore tapped his contents to bring in other heavy hitting names from the comics industry. His Swamp Thing art team of Steve Bissette and Rick Veitch contribute, as do the other artists of his major DC projects: Dave Gibbons, Brian Bolland, and David Lloyd. So do other hot commodities like Bill Sienkiewicz, who had worked with Moore on Brought to Light earlier in the year and would soon start work on Big Numbers, and Frank Miller. Elsewhere are prominent names in British comics that had not broken out in the US: Kevin O’Neil, Bryan Talbot, Mark Buckingham, and Neil Gaiman, whose DC debut would come the next month. And Moore used his increasing literary cache to lure other creators: Art Spiegelman and Robert Crumb both consented to have pieces reprinted in the volume, while Harvey Pekar did a two-pager and Joyce Brabner, with whom Moore had worked on Brought to Light and contributed to her groundbreaking Real War Stories project.

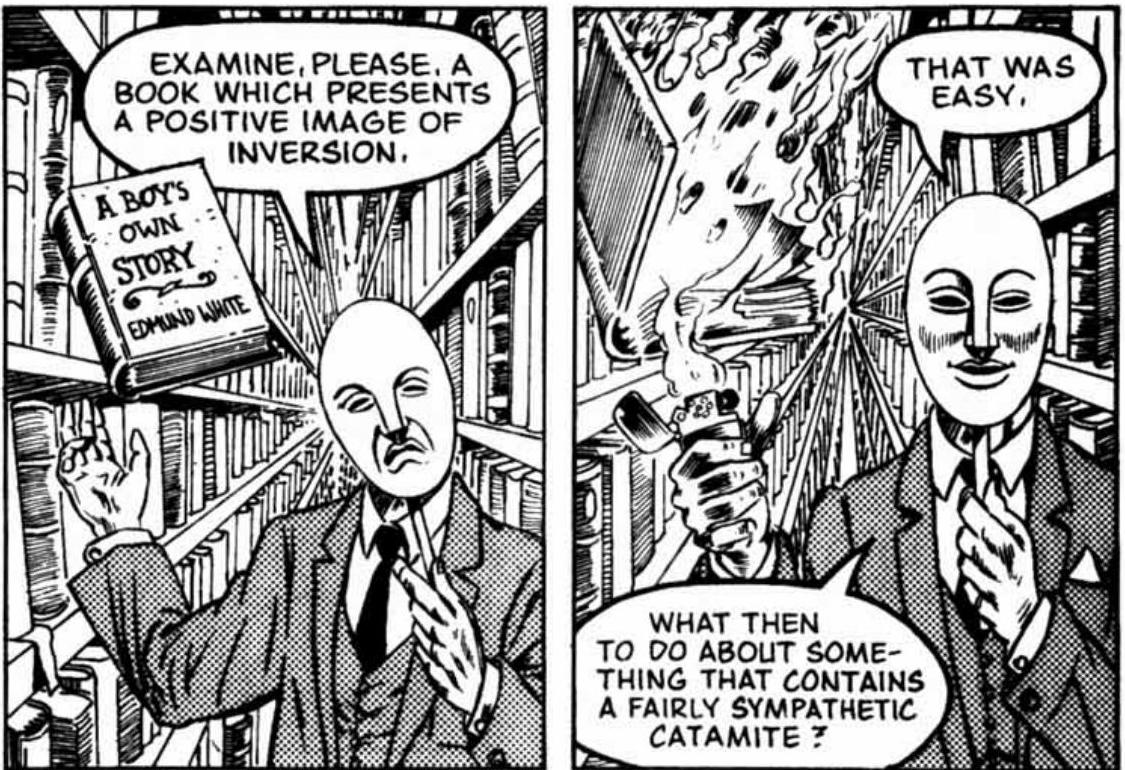

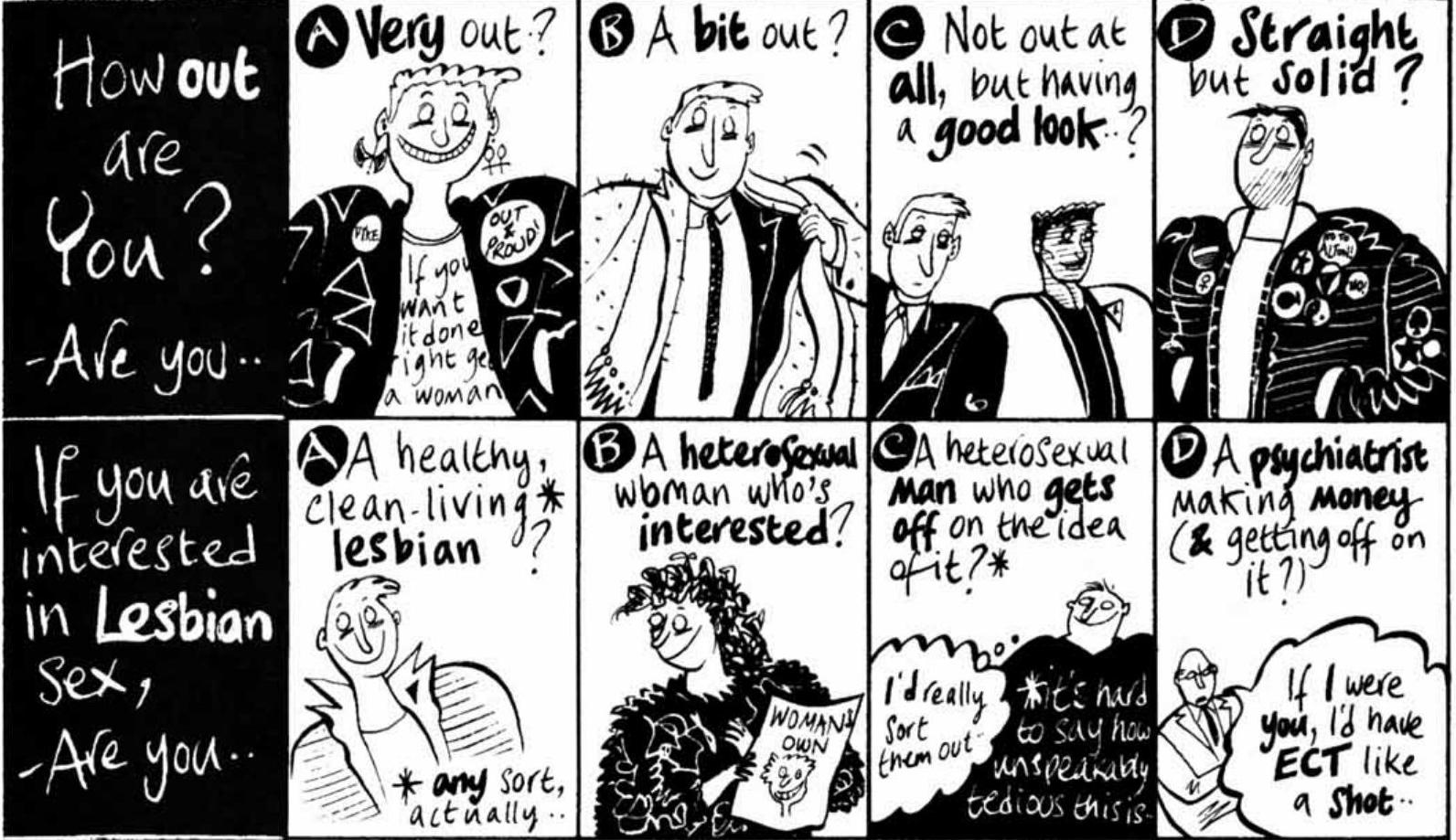

The problem is that none of these names are queer. That is not to say that their pieces are bad, nor that their outrage at Clause 28 is not genuine. But for the most part their investments in the issue are utterly unmoored from the lives and concerns of the queer community. Gaiman, Talbot, and Buckingham’s contribution is indicative, albeit on the better end of the spectrum. Entitled “From Homogenous to Honey,” the four-page strip features a character in a bland suit holding a mask reminiscent of the Greek Comedy and Tragedy masks, albeit, in the first panel, blank and expressionless. Periodically, it wil toggle into a smile or a sneering frown, but it remains fundamentally anonymizing. The man narrates, “good evening, and welcome to our new universe, As you can tell, we’ve made a number of improvements on the old one.” He goes on to explain how these changes were implemented, which is to say through massive censorship. “Examine, please, a book which presents a positive image of inversion,” he says, whilst pointing at a copy of A Boy’s Own Story, Edmund White’s autobiographical novel of adolescent grappling with his homosexuality. “That was easy,” he says in the next panel, flicking open a Zippo to leave the book ablaze.

The strip continues in this vein: the man tours cinema, television, radio, popular music, the theater, and history, alluding to the role of gay people in all of them and demonstrating their elimination and censorship. “The world today is a simpler place,” he concludes. “We’ve taken out all the complications. All the square pegs and the painful and strange. In our utopia, lacking cultural referent for deviancy, all are happy with their lot… everybody is exactly the same. Isn’t it sweet?” This last line is delivered with the man finally removing his mask, revealing an entirely blank white void where his face should be. It’s heavy-handed and didactic, which is of course not a problem in protest art. But it also fundamentally views Clause 28 as bad because it’s an act of censorship—the final panel pointedly quotes Sinclair’s “abstract concept” rhetoric. It is not that Gaiman is wrong to object to the censorship involved in Clause 28, but there’s a distinct sense that he finds the violence done to an abstract concept more urgent than that done to actual people.

The strip continues in this vein: the man tours cinema, television, radio, popular music, the theater, and history, alluding to the role of gay people in all of them and demonstrating their elimination and censorship. “The world today is a simpler place,” he concludes. “We’ve taken out all the complications. All the square pegs and the painful and strange. In our utopia, lacking cultural referent for deviancy, all are happy with their lot… everybody is exactly the same. Isn’t it sweet?” This last line is delivered with the man finally removing his mask, revealing an entirely blank white void where his face should be. It’s heavy-handed and didactic, which is of course not a problem in protest art. But it also fundamentally views Clause 28 as bad because it’s an act of censorship—the final panel pointedly quotes Sinclair’s “abstract concept” rhetoric. It is not that Gaiman is wrong to object to the censorship involved in Clause 28, but there’s a distinct sense that he finds the violence done to an abstract concept more urgent than that done to actual people.

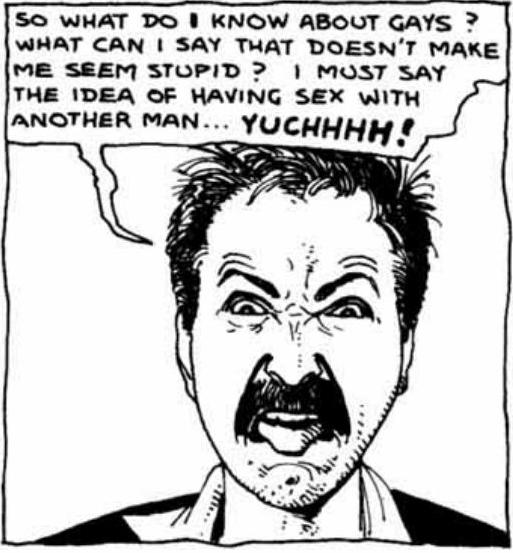

And of the contributors to AARGH! with this particular problem, Gaiman is probably the best of them. Brian Bolland’s contribution, for instance, is a one-page strip in which he states that the real issue is “censorship, loss of liberty, repression, an end to freedom of expression, and that kind of thing.” This assertion comes in between proclaiming, “I must say the idea of having sex with another man…. YUCHHHH!,” declaring that “there’s something about them that makes the short hairs stand up on the nape of the neck,” making clear that he has absolutely no intention of marching against Clause 28 and indeed that he’s opposed to marches in general because “I don’t like the sound of many voices raised in harmony. A harmonious atmosphere reeks of stupidity,” and bemoaning how he can’t draw naked women anymore “what with feminism and everything.” It is not merely disconnected from the gay community but hostile and contemptuous of it—a spiteful and narcissistic whine from a blatant homophobe that’s only concerned that his right to objectify women might be next.

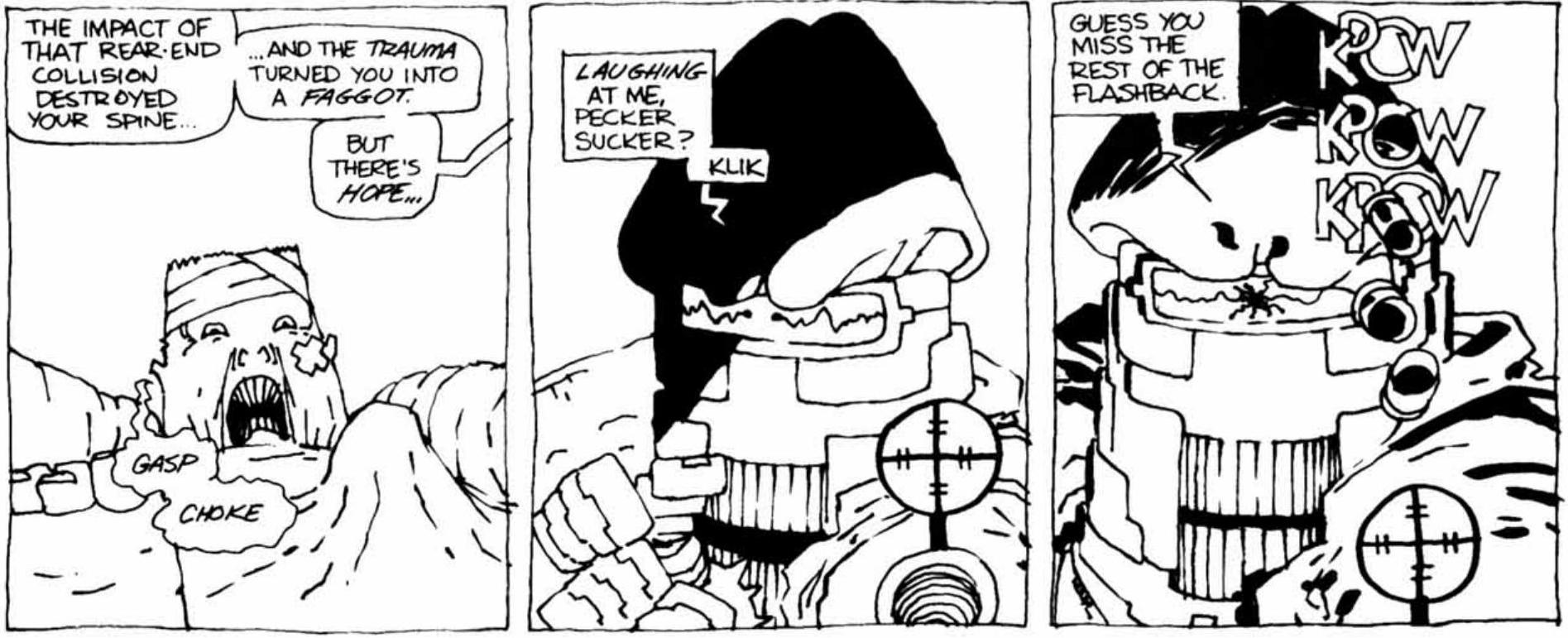

In many ways even worse is Frank Miller’s three-page contribution “The Future of Law Enforcement,” which tells the story of a guy who got into a car crash that turned him gay, resulting in doctors cybernetically rebuilding him into the homosexual hunting Robo-Homophobe. It’s an astonishingly nasty piece of work that manages to suggest that homosexuality is a disability or weakness, that homophobes are all just closeted gay people, and to derive much of its “humor” from the casual deployment of homophobic language. And it’s notable that Miller, like Dave Sim (who also contributes a piece mostly interested in criticizing censors) would eventually make extreme right-wing turns of their own, a well-documented risk of people whose investment in social justice extends only to some broad point that censorship is bad instead of to an actual concern for oppressed populations.

Such stories, to varying degrees, make up a majority of AARGH!, but they are mercifully not the whole of it. The Moores and Delano also tapped members of the queer community for strips. Dave Shenton, Kate Charlesworth, Roz Kaveney, and Kathy Acker all make contributions that are clearly rooted in the lived experience of gay lives, while Alan Moore’s predecessor on Captain Britain tells a story of his own experiences with homophobic bullying, while Jamie Delano turns in a stunning piece in which he puts his skills to adapting the narrative of a twenty-one year old gay man named Mark Vicars. And, of course, the collection ends with a short and angry text piece from Deborah Delano and Phyllis Moore. These pieces are outnumbered and in many ways overwhelmed by the pieces in which white men decry the possibility that homophobia might someday lead inexorably to them not being able to be the edgy provocateurs they dearly wish they were, but their presence makes all but the worst of those pieces feel merely like inept allyship instead of something worse.

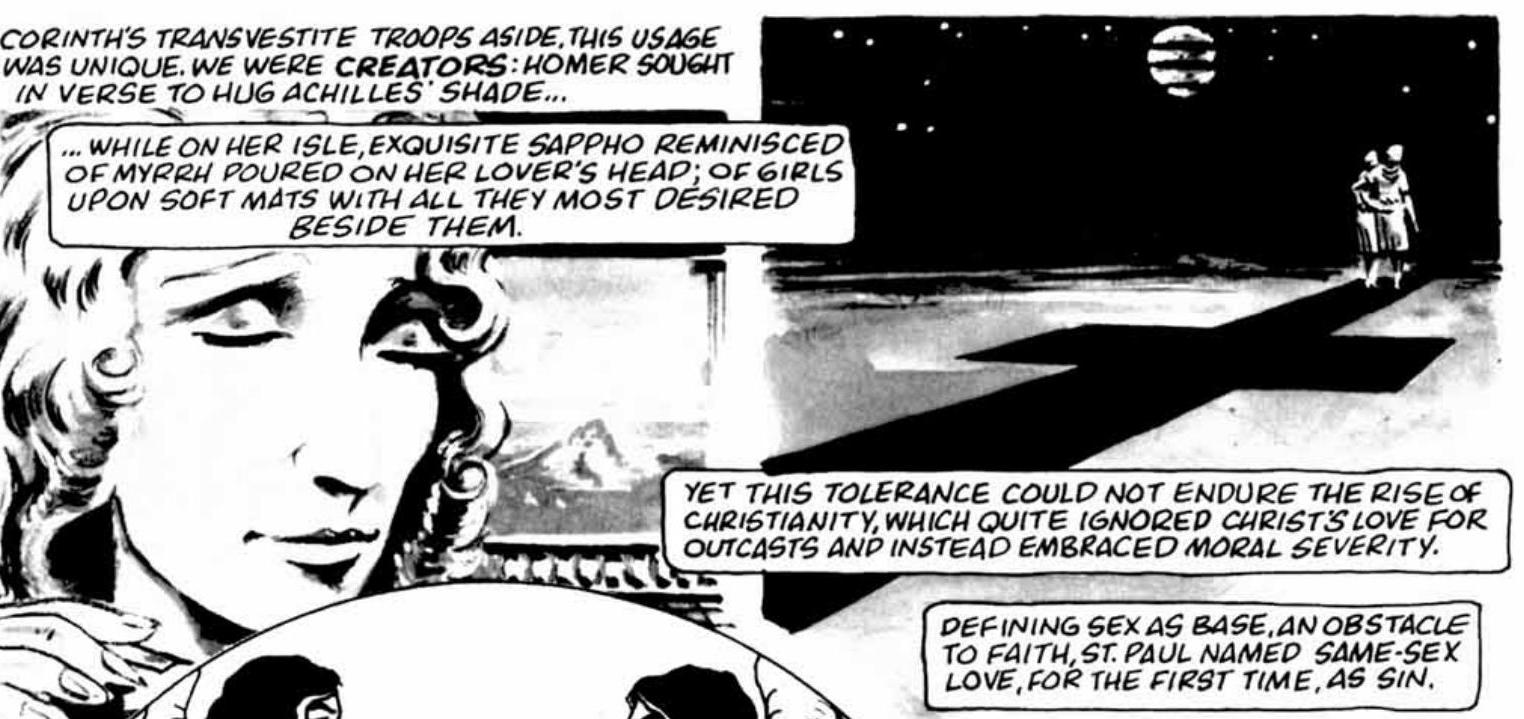

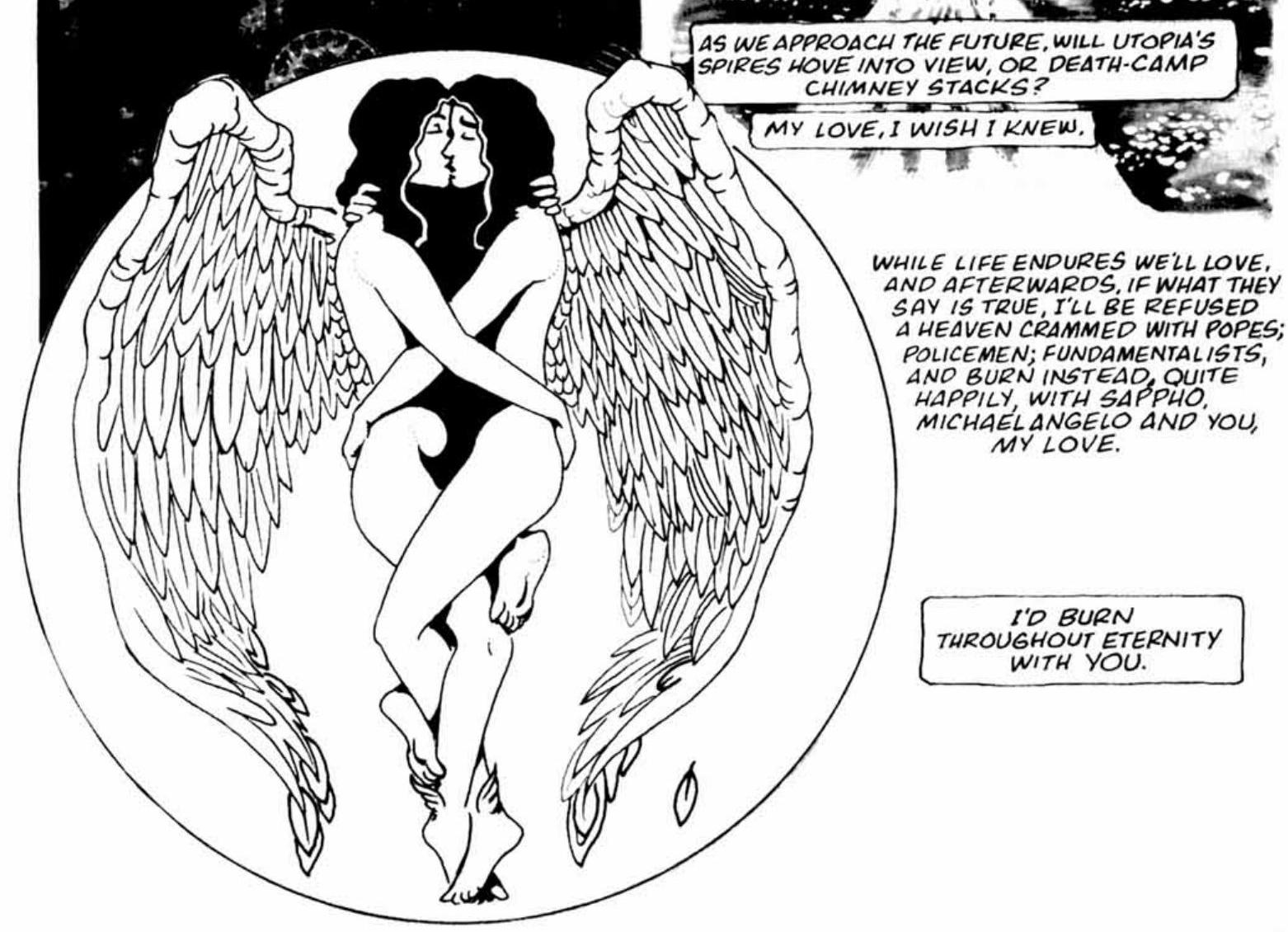

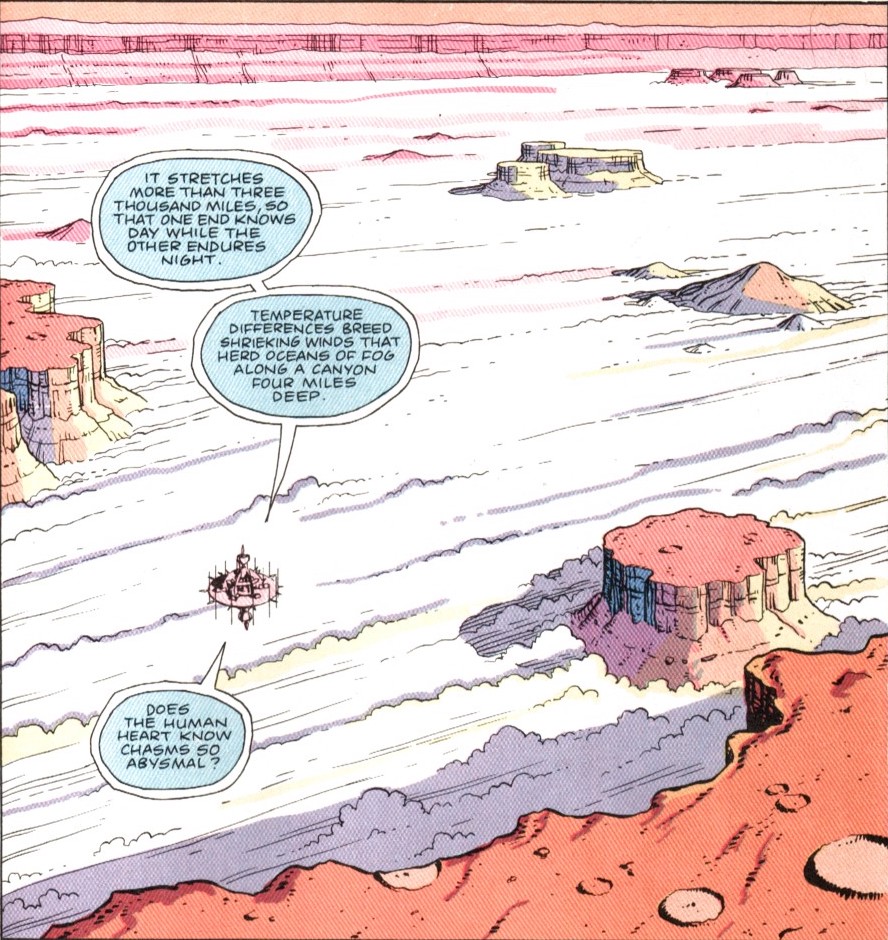

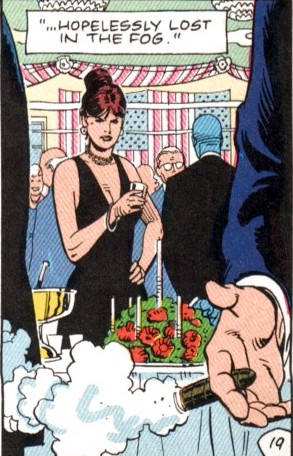

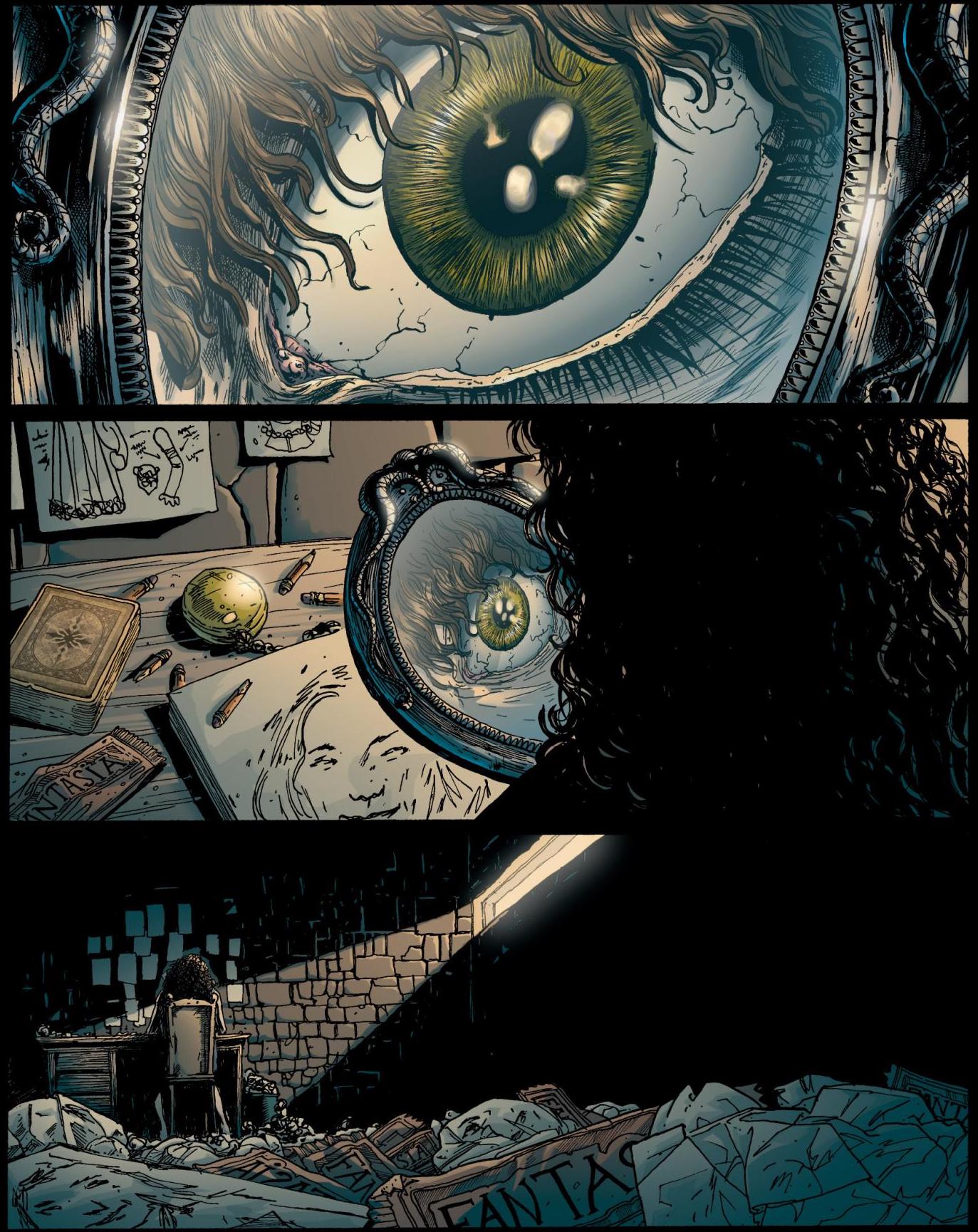

The most notable piece within AARGH! by far, however, is Alan Moore’s own contribution, the eight-page illustrated poem “The Mirror of Love.” The piece is, in effect, a brief history of homosexuality from primordial Earth through the present day. This contains no shortage of discussions of oppression—“In slaughter houses, labeled with pink triangles, our thousands died. The showers, they say, held bodies piled as if the strong and desperate climbed on lovers’ backs to flee the gas, betraying at the last our love, the thing we thought they couldn’t take. Can you imagine? Can you?” But it also contains moments of triumph and celebration of gay achievement: “Homer sought in verse to hug Achilles’ shade… while on her isle, exquisite Sappho reminisced of Myrrh poured on her lover’s head; of girls upon soft mats with all they most desired besides them” But more than the arcs and troughs of gay history, Moore sets out to document the act of queer love. The first page ends, “we gasped upon Devonian beaches, huddled under neolithic stars. Spat blood through powdered teeth, staining each other as we kissed. Always we loved. How could we otherwise, when you are so like me, my sweet, but in a different guise?”

It is not a surprising position for Moore to take. He had, after all, been writing about gay rights since 1984 when he penned the “Valerie” chapter of V for Vendetta, if at the time only as the concerned observer of people like his friend Deborah as opposed to as someone enmeshed in a polyamorous relationship whose own family was being threatened by his government. And the focus on sexual expression is a natural extension of the arguments he was making in “A Brother To Dragons.” Nevertheless, it is notable that Moore is the only person in AARGH! to offer any sense of the erotic. Where the other contributors seek to speak out against Clause 28, Moore is determined to defy it, depicting and promoting homosexuality and daring anyone to call it “pretended.” It is furious and beautiful all at once, its final proclamation that “I’d burn throughout eternity with you” feeling wholly and entirely earned and honest.

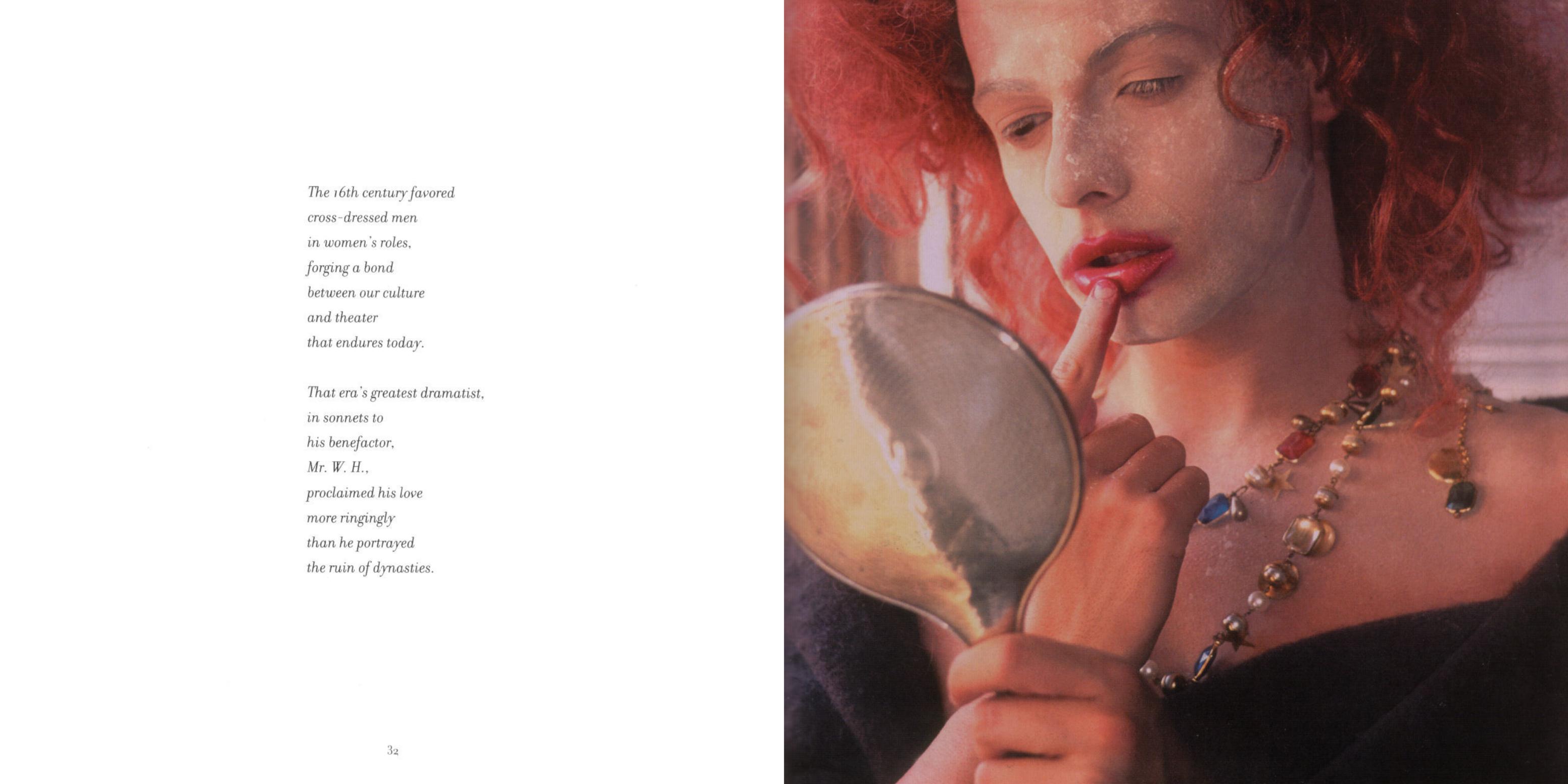

A decade later, artist José Villarubia discovered the piece in the British counterculture magazine Rapid Eye, where it was reprinted alongside an interview with Alan Moore (and an essay by Grant Morrison on avant garde filmmaker Maya Deren). Moved by it, Villarubia enlisted his friend, theater director David Drake, to direct him in a solo performance of the piece, which was performed as a monologue to a sleeping lover and delivered nude by Villarubia at the Baltimore Theater Project. (Upon watching a videotape of the performance with Melinda Gebbie, either Moore or Gebbie are reported to have noted, “nice ass,” although which depends on which time Moore is telling the story.) Villarubia, an accomplished comics artist himself who would go on to be the colorist on Promethea, was eventually inspired to do a second adaptation, this time as a book with forty photographs illustrating the poem.

The poem would also mark something of a turning point in Moore’s own style. As he notes, ““I had naively assumed that I’d be able to research this thing by going down to the local reference library and getting a good reference book on the history of gay culture. I was soon disabused of this notion, because I realized that there wasn’t an overall history that existed at that time.” This meant that he had to instead engage in detailed research and coordinate information from multiple sources. This was at the same time he was doing similar work for Brought to Light, where he had to try to synthesize the entire dirty history of the CIA. As he put it, “In the morning I’d be researching sodomy and heresy in early modern Switzerland, and in the afternoon I’d be researching heroin smuggling in Thailand during the 70s.” He discovered, however, that he found research satisfying, and began to imagine fundamentally different sorts of comics—ones that would not simply be illustrated primers on a subject like “The Mirror of Love” and Brought to Light, but that would nevertheless make use of similarly dense and expansive research. That, however, is a story for another time.

AARGH! was in practice a successful piece of fundraising—Gary Spencer Millidge’s Alan Moore: Storyteller says it raised around £17,000 for the Organization for Lesbian and Gay Action, while Delano pegs the figure at £10,000. Moore suggests the donation was not actually entirely well-received, noting that “they were militant, bigoted, half-arsed. When we actually met them they didn’t even like the fact that—I mean it was Phyllis and Debbie who went to deal with them—the fact that Phyllis and Debbie said that they were bisexual. This, you know, ‘Huh! Accepting money from bisexuals!’ I think one of them said ‘We’ll be allowing men in next!’” For a variety of reasons, this is probably an instance of Moore misremembering events. Two representatives of OLGA, Jennie Wilson and Lisa Power, contributed to AARGH! And at the organization’s general meeting in Edinburgh the month before AARGH! came out, Jennie Wilson introduced an explicit statement of bisexual inclusion which was adopted with only two opposing votes. A further perusal of the minutes for this meeting reveal that the leadership of OLGA consisted of both men and women. While it is likely that Moore or his family did encounter lesbian separatist attitudes in the general case—Delano has written witheringly about lesbian separatists in the 80s, although she doesn’t tell anything like this story when recounting her Clause 28 activism in The Things You Do—his suggestion that these attitudes were expressed on an institutional level in response to a substantial fundraising donation seems deeply implausible.

The timeline of Delano’s life grows fuzzier in the immediate aftermath of her Clause 28 activism. Some things are clear: she remained a presence in Leah and Amber’s life, including a spell in 2000 when, after a bad breakup, she went to live in Liverpool with Phyllis and slept in Amber’s bed, sharing it once Amber came home from university. In 1995, she moved to London and became a sociology teacher. Distressed by the casual homophobia shown by many of her students, she resolved to come out to her students when a reasonable opportunity presented itself, which it finally did in 1997. She recounted the experience in an article for Dodgem Logic in 2010, and recycled much of the recounting four years later in The Things You Do. After a few initial moments of shock, the students took it well and she proceeded to field questions. When, shortly before the bell, one of the boys asked for an account of lesbian sex, he was quickly shushed for “disrespecting Miss.” She got some harassment from students, and was called a pervert by the school’s head of religious education, which led to a meeting with her superiors in which the woman loudly lashed out at her. (Delano quietly left he meeting, and the woman subsequently approached her in tears begging forgiveness.) But for the most part it went well, and she commenced a policy of being fully and vocally out of the closet in all circumstances.

The timeline of Delano’s life grows fuzzier in the immediate aftermath of her Clause 28 activism. Some things are clear: she remained a presence in Leah and Amber’s life, including a spell in 2000 when, after a bad breakup, she went to live in Liverpool with Phyllis and slept in Amber’s bed, sharing it once Amber came home from university. In 1995, she moved to London and became a sociology teacher. Distressed by the casual homophobia shown by many of her students, she resolved to come out to her students when a reasonable opportunity presented itself, which it finally did in 1997. She recounted the experience in an article for Dodgem Logic in 2010, and recycled much of the recounting four years later in The Things You Do. After a few initial moments of shock, the students took it well and she proceeded to field questions. When, shortly before the bell, one of the boys asked for an account of lesbian sex, he was quickly shushed for “disrespecting Miss.” She got some harassment from students, and was called a pervert by the school’s head of religious education, which led to a meeting with her superiors in which the woman loudly lashed out at her. (Delano quietly left he meeting, and the woman subsequently approached her in tears begging forgiveness.) But for the most part it went well, and she commenced a policy of being fully and vocally out of the closet in all circumstances.

In the early aughts, she met a French accountant named Martine, entered a “civil partnership” in 2006, this being all that was permitted before 2014. (She notes that “marriage is a profoundly conservative institution anyway, and hopelessly embedded in patriarchy.” Some years after this (one expects before 2010), she slipped on a patch of ice while walking and badly broke her arm. While convalescing from this, she was inspired to begin writing a memoir on the logic that much of both the working class and lesbian histories she came out of were oral traditions that thus got erased or heavily mediated in the course of being recorded, noting that “This is a narrative that I thought worth telling about a people that I needed to immortalise because they’re brilliant. I wanted to put them up there in the collective conscience.” One can see echoes here of Moore’s logic in Jerusalem: “I’ve saved the Boroughs, Warry, but not how you save the whale or save the National Health Service. I’ve saved it the way you save ships in bottles. It’s the only plan that works. Sooner or later all the people and the places that we loved are finished, and the only way to keep them safe is art. That’s what art’s for. It rescues everything from time.” Or even in Watchmen, after Doctor Manhattan calls Laurie a thermodynamic miracle, and she objects that this is true of anybody: “Yes. Anybody in the world. But the world is so full of people, so crowded with these miracles that they become commonplace and we forget. I forget. We gaze continually at the world and it grows dull in our perceptions. Yet seen from another’s vantage point, as if new, it may still take the breath away.”

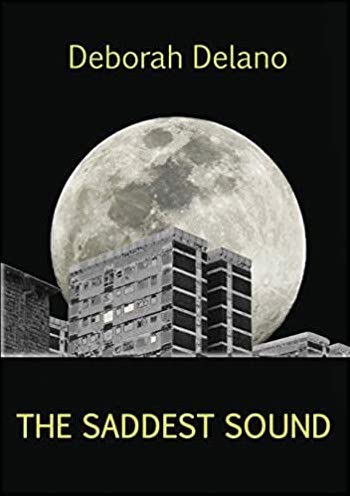

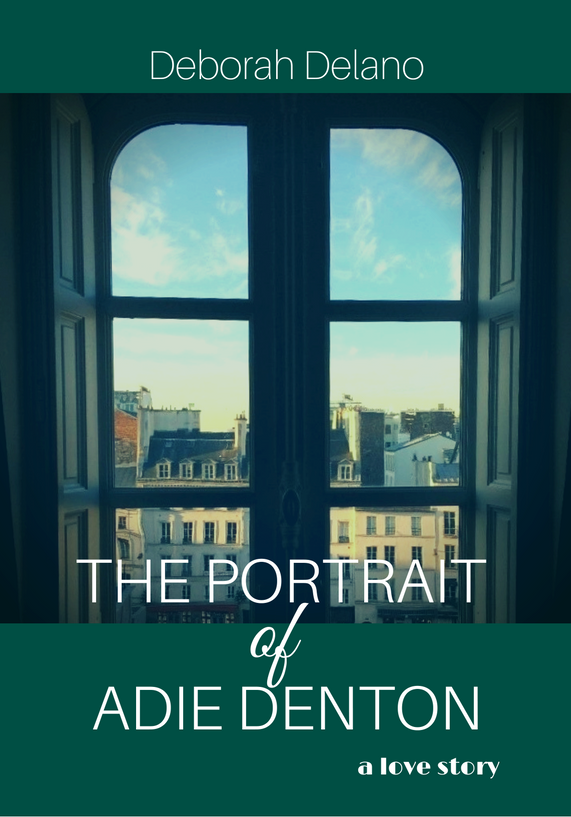

Delano originally intended to circulate the book among friends and family, but was urged by Leah Moore to publish it more wisely. Eventually Jamie Delano, by this point running a small press called Lepus Books through which he publishes a number of other writers from his and Alan Moore’s Northampton social circle including Alistair Fruish and Richard Foreman, offered to publish it, and Delano, by this point already working on her first novel, decided “what the hell.”

The resulting book is an odd document. Little to no effort is made to provide any sort of general interest hook for it. Delano simply presents an account of her life, starting from her family background and working forwards to about 1987 before fast-forwarding through the last couple decades and ending with an oblique coda in which she visits the widow of her biological father claiming to be researching “refugees who’d set up home in Northampton after the war” and getting a fuller story of his life. The book’s ambitions are as she describes: a simple documentation of the life of one working class British lesbian in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. This is, to be sure, tremendously interesting—Delano’s prose is lively and functional, and she does well at offering a sense of texture to the already lost world she conjures up. But its ambitions are pointedly modest, and all the better for it. The book’s origins as a document intended for friends and family give it a strange and pleasant confidence—it does not for a moment doubt that the story of Delano’s life is interesting, and justifies itself in the process.

The resulting book is an odd document. Little to no effort is made to provide any sort of general interest hook for it. Delano simply presents an account of her life, starting from her family background and working forwards to about 1987 before fast-forwarding through the last couple decades and ending with an oblique coda in which she visits the widow of her biological father claiming to be researching “refugees who’d set up home in Northampton after the war” and getting a fuller story of his life. The book’s ambitions are as she describes: a simple documentation of the life of one working class British lesbian in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. This is, to be sure, tremendously interesting—Delano’s prose is lively and functional, and she does well at offering a sense of texture to the already lost world she conjures up. But its ambitions are pointedly modest, and all the better for it. The book’s origins as a document intended for friends and family give it a strange and pleasant confidence—it does not for a moment doubt that the story of Delano’s life is interesting, and justifies itself in the process.

As for the book’s most obvious hook, it is carefully avoided—Phyllis and Alan Moore pop up regularly, but are referred to only by their first names, the details of their relationship kept oblique. Accounts of visiting Delano’s father with both Phyllis and the kids come up, and both AARGH! and Big Numbers are mentioned, but the fact that Delano is talking about one of the most famous writers in Britain is left obscure. To some extent this is a deliberate choice—Delano notes in the one interview she did for the book that “There were areas of my life that warranted a slightly more oblique approach—namely my relationship with Alan and Phyllis and their children, which is I suspect the people and events to which you refer. Given that anything pertaining to Alan’s private life might attract unwanted attention I included only such details that were relevant to describe the friendship we have (and still do enjoy) and the political work we were jointly involved in” before defending Moore against accusations of misogyny. But it also makes sense in terms of what the book is—a document of a life that is entirely fascinating on its own merits.

As for the book’s most obvious hook, it is carefully avoided—Phyllis and Alan Moore pop up regularly, but are referred to only by their first names, the details of their relationship kept oblique. Accounts of visiting Delano’s father with both Phyllis and the kids come up, and both AARGH! and Big Numbers are mentioned, but the fact that Delano is talking about one of the most famous writers in Britain is left obscure. To some extent this is a deliberate choice—Delano notes in the one interview she did for the book that “There were areas of my life that warranted a slightly more oblique approach—namely my relationship with Alan and Phyllis and their children, which is I suspect the people and events to which you refer. Given that anything pertaining to Alan’s private life might attract unwanted attention I included only such details that were relevant to describe the friendship we have (and still do enjoy) and the political work we were jointly involved in” before defending Moore against accusations of misogyny. But it also makes sense in terms of what the book is—a document of a life that is entirely fascinating on its own merits.

For Moore, of course, establishing the timeline is altogether simpler. Even in his most private and withdrawn periods, and the first couple years of the 1990s are certainly that, there exists a substantial record of works both major and minor, from the starts of his three intended magnum opuses, Big Numbers, From Hell, and Lost Girls, to a smattering of smaller pieces in various venues and, eventually, his public declaration that he was a snake puppet worshipping occultist, return to the mainstream comics scene, and involvement in what is the better part of an entire magical war for the soul of Albion.

He is, in other words, neither silent nor hidden, but rather a giant—a landscape unto himself, visible from vast distances, his contours defining their context as much as the other way around. His story is easy, in almost precise contrast to the history of working class lesbians, which vanishes almost as soon as it’s told. That he understands this and has sympathy for it—that he even has his own vanishing past that he’ll work to preserve—fundamentally does not change the fact that he is a creature of eternity and she is not, and that the most meticulous portrait of Deborah Delano that can be built out of the public record is still more full of gaps and silences than what can be discovered about even one of his minor works. (And consider for comparison Phyllis, who disappears from the narrative entirely after their split, becoming a wholly private figure. Is her story less interesting than Delano’s or Moore’s for its absence?)

He is, in other words, neither silent nor hidden, but rather a giant—a landscape unto himself, visible from vast distances, his contours defining their context as much as the other way around. His story is easy, in almost precise contrast to the history of working class lesbians, which vanishes almost as soon as it’s told. That he understands this and has sympathy for it—that he even has his own vanishing past that he’ll work to preserve—fundamentally does not change the fact that he is a creature of eternity and she is not, and that the most meticulous portrait of Deborah Delano that can be built out of the public record is still more full of gaps and silences than what can be discovered about even one of his minor works. (And consider for comparison Phyllis, who disappears from the narrative entirely after their split, becoming a wholly private figure. Is her story less interesting than Delano’s or Moore’s for its absence?)

Thankfully, once bitten by the writing bug, Delano found herself newly invigorated and determined to use her voice. (As she writes in an article for Singletrack, a British mountain biking magazine, about taking up mountain biking late in life at the behest of her wife, just as “I am ‘finding my lines’ between rocks and ridges, tree roots and solid earth, hairpins and stingers,” “I am finding my lines—the well-turned phrase, the perfect word, the beautifully constructed narrative.”) She quickly moved on to her first novel entitled The Saddest Sound. A crime novel set in 1979 and 1980 Liverpool, The Saddest Sound draws on her childhood knowledge of true crime to craft a tale based loosely on the murders of Peter Sutcliffe, popularized in tabloids as the Yorkshire Ripper.

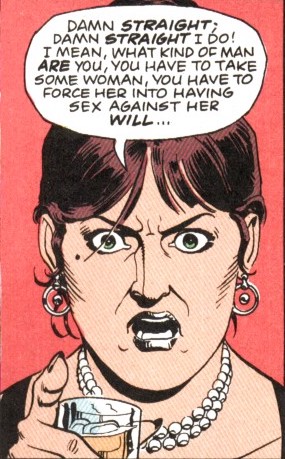

In practice, however, almost nothing of what is evoked by that description applies. Delano takes the refreshing spin of focusing on the women who make up the space around the killings. The killer himself—a violent misogynist who murders then rapes women—is characterized, but not with any of the perverse fascination of most serial killers. He is simply a thing that happens—an inevitable consequence of endemic toxic masculinity that is in no way interesting on his own merits. And so instead Delano sketches the space around him. This includes, obviously, pen portraits of his victims, a series of starkly tragic chapters in which a character is introduced only to meet a grisly end when she encounters the killer. But this is only the tip of the iceberg.

The primary characters in the novel are Sandra and Tracy, a pair of lesbian sex workers who open the book trying and failing to get custody of Sandra’s son away from his abusive father, and close it with custody and a degree of financial security from Tracy’s newly started hauling business. Close seconds are Irina, the serial killer’s abused and mentally fragile wife, and Selene, Irina’s sister, an academic sociologist living with a bunch of lesbian activists. (Her name is almost certainly an homage to Steve Moore, who Delano notes in the acknowledgments “sadly died just before I sent him the first draft of the manuscript.”) And there’s a wider galaxy of other sex workers and radical feminists circling around this core (including a deliciously savage portrayal of a TERF that drips with all the contempt of someone who has been rolling her eyes at them for forty years), all of them grappling with the reality that there’s a serial killer attacking their communities.

It would certainly not be wrong to point out the influence of Delano’s old friend on this. The basic method of The Saddest Sound would be recognizably drawn from From Hell even if you didn’t know their writers used to be romantically entangled. Just as From Hell uses the Ripper murders as a lens through which to see the whole of Victorian England and the closing of the 19th century, Delano is using a serial killer to understand a the lives of women, particularly working class women, at the dawn of Thatcher’s Britain. The plot of the novel, broadly speaking, consists of Selene, with the help of Tracy and Sandra (who narrowly survives one of the killer’s attacks), figuring out who the killer is and getting the police to believe them. (This latter step consumes the latter third of the book, a grim reality of how much credence is actually given to the voices of sex workers and queer people.) But just as From Hell is not about the unmasking of William Gull as Jack the Ripper, The Saddest Sound is not about solving the crime; it’s about the lives of the women, how they grow and change, and what the texture of their day to day existence is like.

But this also highlights the key differences between Delano’s work and her ex-boyfriend’s. Delano is not interested in grandiose metaphysical explanations of the world. It’s not that there’s no whiff of magic or the supernatural in The Saddest Sound—the book features a recurring motif of condors and clear credence is given to people’s sense of premonition and foreboding. But the murders depicted are ultimately just grubby acts of cruelty and violence perpetuated against marginalized people, not some secret key to the impending twenty-first century. There’s no sort of hyper-completionist mania running through the book in which Delano tries to track down every facet of Thatcher’s Britain to try to gesture at some complete picture of the thing. There’s just a story about people.

Indeed, Delano finds time within her book to poke fun at her former lover’s magnum opus. At one point she has Selene—whose background in sociology makes her the character through which Delano can most easily deliver authorial analysis on events—comment that “I did a fair bit of research on the Jack the Ripper thing. They tried to make him a character in a Victorian melodrama. He was a surgeon, an aristocrat, a prince, an evil Jew, a demented Pole. You know what, he was an ordinary bloke. He must have ben. He was invisible precisely because he was a nobody. He must have lived in the East End, he’d have had to have a place to clean up. How many aristocrats lived in Whitechapel?” Delano may borrow the mode of analysis, but she has no patience for or interest in the way From Hell centers its killer and fixates on the deep nuances of his pathology. Delano’s killer does what he does because he’s a fucked up misogynist within an intergenerational cycle of misogynistic abuse. He isn’t seeking some savage apotheosis to shatter the bonds of the fourth dimension; smashing women’s faces in with hammers just gets him hard. In this, he is deliberately, carefully the least interesting character in the story.

Indeed, Delano finds time within her book to poke fun at her former lover’s magnum opus. At one point she has Selene—whose background in sociology makes her the character through which Delano can most easily deliver authorial analysis on events—comment that “I did a fair bit of research on the Jack the Ripper thing. They tried to make him a character in a Victorian melodrama. He was a surgeon, an aristocrat, a prince, an evil Jew, a demented Pole. You know what, he was an ordinary bloke. He must have ben. He was invisible precisely because he was a nobody. He must have lived in the East End, he’d have had to have a place to clean up. How many aristocrats lived in Whitechapel?” Delano may borrow the mode of analysis, but she has no patience for or interest in the way From Hell centers its killer and fixates on the deep nuances of his pathology. Delano’s killer does what he does because he’s a fucked up misogynist within an intergenerational cycle of misogynistic abuse. He isn’t seeking some savage apotheosis to shatter the bonds of the fourth dimension; smashing women’s faces in with hammers just gets him hard. In this, he is deliberately, carefully the least interesting character in the story.

There is another comparison that is worth making here—to the handling of sexual violence and its effects on women in Watchmen. There is a well-intentioned camp of criticism that finds fault in the reveal that Sally Jupiter, after being raped by the Comedian, went on to have consensual sex with him, and even holds clear emotional affection for him at the end of the comic, tearfully kissing his photograph in her final scene. In many framings this criticism is deeply flawed, most obviously when it is phrased in such a way as to suggest that the comic forgives or excuses the Comedian’s actions. This is clearly unsupported by the text. Nor is it honest to suggest that the comic is presenting something unrealistic or exploitative. Indeed, given the degree to which rape victims are routinely dismissed because their subsequent emotional relationships with their attackers fail to fit the tidy narrative of a “perfect victim,” stories in which survivors display complicated emotions are good and important. Reading Watchmen, one gets the strong impression that this plot point is written by someone who has had experience with survivors of sexual assault, and who genuinely cares about capturing the complex realities of that experience. And yet for all of this, there is a tangible difference between Watchmen’s handling of sexual violence and The Saddest Sound’s. Watchmen feels like it is written by someone with knowledge of and real concern about sexual violence; The Saddest Sound feels like it is written by someone who has lived in communities where it is a routine reality of life. Watchmen deals with the subject in unusual nuance, especially for a cisgender and heterosexual male writer, but it cannot hold a candle to The Saddest Sound’s sense of the details and particular anguishes of it.

Delano cannot quite get the story to do all that she evidently wants it to. In its latter sections, the narrative becomes unduly focused on the police detective investigating the crimes, and most of the lengthy epilogue uses him as a viewpoint character to look in at the families of the killer’s various victims. It returns to Sandra and Tracy for the closing moments, as it has to for the book to have any integrity, but there’s still far more focus on a virtuous male cop in the book’s closing stages than its ambitions want. But then again, it’s a first novel, not the even more accomplished follow-up to an artistic masterpiece that shifted the course of history. Perhaps the level of artistic craft doesn’t quite match From Hell; it’s a damn sight more impressive than Skizz. (As for him? She notes that his “constant encouragement and support gave me confidence to write in the first place,” while he offered a blurb proclaiming that “compassionately observed characters, an insightful grasp of period and landscape, and a fine touch with the dreadful and unsettling conspire to make The Saddest Sound the most involving novel of its kind that you will read this year.”)

Delano cannot quite get the story to do all that she evidently wants it to. In its latter sections, the narrative becomes unduly focused on the police detective investigating the crimes, and most of the lengthy epilogue uses him as a viewpoint character to look in at the families of the killer’s various victims. It returns to Sandra and Tracy for the closing moments, as it has to for the book to have any integrity, but there’s still far more focus on a virtuous male cop in the book’s closing stages than its ambitions want. But then again, it’s a first novel, not the even more accomplished follow-up to an artistic masterpiece that shifted the course of history. Perhaps the level of artistic craft doesn’t quite match From Hell; it’s a damn sight more impressive than Skizz. (As for him? She notes that his “constant encouragement and support gave me confidence to write in the first place,” while he offered a blurb proclaiming that “compassionately observed characters, an insightful grasp of period and landscape, and a fine touch with the dreadful and unsettling conspire to make The Saddest Sound the most involving novel of its kind that you will read this year.”)

For now, at least, this marks the whole of what is visible about Deborah Delano’s life. Her second novel, The Portrait of Adie Denton, remains unpublished. (She describes it as “an inter-class, queer love story set largely in Paris, against the backdrop of the fabulously wealthy lesbian demi-monde. To place the work within a canon, it is Sarah Waters meets Armistead Maupin on the set of Upstairs Downstairs.”) Beyond that, nothing is knowable within the confines of good taste and respect for privacy.

How then, is this to be understood? On the one hand, Delano is eclipsed by Moore, a secondary character in her own story, like some third string comics character in an issue guest-starring Superman or Batman. Even the most focused recounting of her life eventually must concede the point and gesture out at the towering vista that is her one-time boyfriend. On the other, what visibility her life has extends from him. Her two books exist within the public sphere because Jamie Delano, a friend she met through Moore, has a publishing company; that company exists because he had a moderately successful comics career that was spurred largely by Moore’s endorsement. Take him out of the equation and the whole structure that grants insight into Delano’s life crumbles. As, perhaps, does her life, ended in 1981 with a single flash of misogynistic violence by her girlfriend’s jealous ex. The paradox is unresolvable. Moore both eclipses and illuminates. He is responsible for why it is possible to discover the rich, lush tapestry of working class queer life in the 1980s, but he also establishes the limits of that perception—the point in the image where it gives way to frame. Quite literally, in fact: Delano’s biggest elisions in The Things You Do are made in deference to his privacy.

How then, is this to be understood? On the one hand, Delano is eclipsed by Moore, a secondary character in her own story, like some third string comics character in an issue guest-starring Superman or Batman. Even the most focused recounting of her life eventually must concede the point and gesture out at the towering vista that is her one-time boyfriend. On the other, what visibility her life has extends from him. Her two books exist within the public sphere because Jamie Delano, a friend she met through Moore, has a publishing company; that company exists because he had a moderately successful comics career that was spurred largely by Moore’s endorsement. Take him out of the equation and the whole structure that grants insight into Delano’s life crumbles. As, perhaps, does her life, ended in 1981 with a single flash of misogynistic violence by her girlfriend’s jealous ex. The paradox is unresolvable. Moore both eclipses and illuminates. He is responsible for why it is possible to discover the rich, lush tapestry of working class queer life in the 1980s, but he also establishes the limits of that perception—the point in the image where it gives way to frame. Quite literally, in fact: Delano’s biggest elisions in The Things You Do are made in deference to his privacy.

Some time not long after AARGH! was published, the relationship fell apart. Delano, Phyllis, and the kids left and moved to Liveprool. Moore stayed behind in Northampton. Dating the event is difficult. Moore has said that it lasted “two or three years,” but with no start date this is not helpful. Lance Parkin compiles contradictory dates from a number of sources: Moore saying “about 1989,” Moore dating the length of his marriage at thirteen years, Moore saying he moved house in 1988, Moore saying the split happened “some short time after” the V for Vendetta introduction, and Leah Moore recalling it when she was 12, which would have been 1990. The particulars of what happened are entirely obscure; speculation is possible, but becomes ghoulish with such rapidity as to be worthless. Even in the most comprehensive of histories, some details are best left quiet.

Some time not long after AARGH! was published, the relationship fell apart. Delano, Phyllis, and the kids left and moved to Liveprool. Moore stayed behind in Northampton. Dating the event is difficult. Moore has said that it lasted “two or three years,” but with no start date this is not helpful. Lance Parkin compiles contradictory dates from a number of sources: Moore saying “about 1989,” Moore dating the length of his marriage at thirteen years, Moore saying he moved house in 1988, Moore saying the split happened “some short time after” the V for Vendetta introduction, and Leah Moore recalling it when she was 12, which would have been 1990. The particulars of what happened are entirely obscure; speculation is possible, but becomes ghoulish with such rapidity as to be worthless. Even in the most comprehensive of histories, some details are best left quiet.

As Moore would say a few years later, describing a different upheaval in his life, “within a fortnight, it can all fall down.” The breakup presaged what, as mentioned, was a particularly sparse few years from him. Perhaps the most immediate casualty was Moore’s in progress comics project, Big Numbers, which he put out via Mad Love and had Delano and Phyllis editing, although what happened there went well beyond the collapse of Moore’s marriage and is a story for another time. Moore’s other projects of the period faltered as well, again for reasons that cannot simply be traced to his state of mind after the divorce, but which also wouldn’t need additional reasons to be understandable.

As Moore would say a few years later, describing a different upheaval in his life, “within a fortnight, it can all fall down.” The breakup presaged what, as mentioned, was a particularly sparse few years from him. Perhaps the most immediate casualty was Moore’s in progress comics project, Big Numbers, which he put out via Mad Love and had Delano and Phyllis editing, although what happened there went well beyond the collapse of Moore’s marriage and is a story for another time. Moore’s other projects of the period faltered as well, again for reasons that cannot simply be traced to his state of mind after the divorce, but which also wouldn’t need additional reasons to be understandable.

Moore is a creature of Eternity. But even his constancy has its gaps—moments in which he changes. The nature of these changes is complicated, relating not so much to his fundamental nature as to what that nature means in a larger context. A decade earlier, he transformed from a disaffected ex-hippy slowly anesthetizing his creative spirit into a giant of the comics landscape, a change that was not affected by becoming a different sort of person, but rather through a titanic shift of perspective, organizing his life around his love of the counterculture instead of the expectations laid upon a working class dropout.

Now the direction of his life shifts again. Caught up in a disorienting combination of emotional upheaval, celebrity, creative ambition, amidst the burnt bridges of his four years at DC and the larger fallout of being the man who wrote Watchmen, it was time for what it meant to be Alan Moore to change once more. And this would be the most tectonic shift yet.

Now the direction of his life shifts again. Caught up in a disorienting combination of emotional upheaval, celebrity, creative ambition, amidst the burnt bridges of his four years at DC and the larger fallout of being the man who wrote Watchmen, it was time for what it meant to be Alan Moore to change once more. And this would be the most tectonic shift yet.

“There are the tales the women tell, in the private tongue men-children are never taught and older men are too wise to learn. And these tales are not told to men.” – Neil Gaiman, Sandman #9

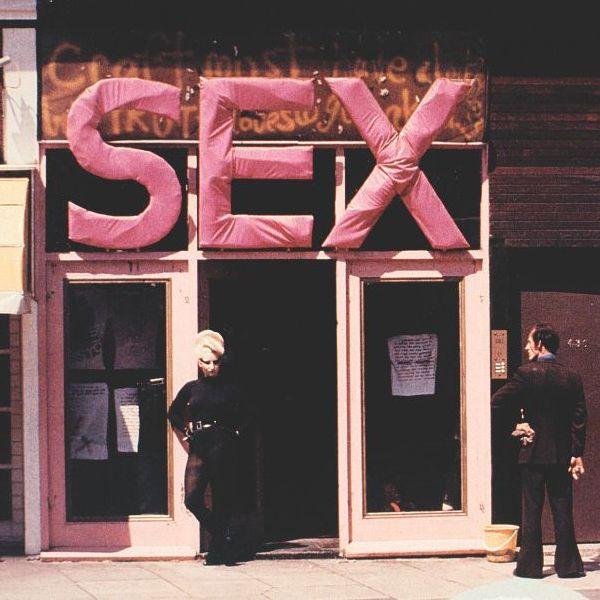

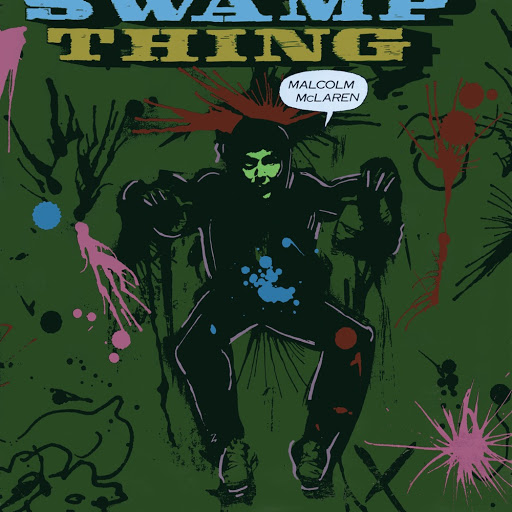

{In the summer of 1985, a few months after he’d written the script for Watchmen #1, Alan Moore was visited in Northampton by a man seeking to commission him to write a screenplay. This was not intrinsically work that interested Moore, who had little interest in getting sucked into the quagmire of Hollywood, but he was sufficiently intrigued by the opportunity to meet and work with the man that he accepted. The screenplay would be called Fashion Beast, and would never get made, although Avatar published a comics adaptation in 2012. The man was Malcolm McLaren.

{In the summer of 1985, a few months after he’d written the script for Watchmen #1, Alan Moore was visited in Northampton by a man seeking to commission him to write a screenplay. This was not intrinsically work that interested Moore, who had little interest in getting sucked into the quagmire of Hollywood, but he was sufficiently intrigued by the opportunity to meet and work with the man that he accepted. The screenplay would be called Fashion Beast, and would never get made, although Avatar published a comics adaptation in 2012. The man was Malcolm McLaren.

That Moore would be so eager to meet with McLaren is in some regards ironic, given that at first glance McLaren would seem to serve as a mirror image of the man who would soon proclaim himself Moore’s nemesis—a shadow Morrison, transplanted from a magical war into a different sort of effort to dragoon the world’s culture down a particular path, the Peter Cannon to his Ozymandias. (The simpler explanation, of course, would be that McLaren was a direct inspiration for Morrison, but this has surprisingly scant evidence in support of it; Morrison cites the Sex Pistols as a favorite band in several interviews and talks about the overall influence of punk on him, but has never spoken about McLaren in any depth.) In truth, the relationship is more complex, and a survey of McLaren’s upbringing reveals strange parallels across the War.

Born in the aftermath of the more grimly prosaic Second World War, Malcolm McLaren was the son of Peter McLaren, a Scottish car mechanic and Emily Isaacs, a young woman from one of North London’s Jewish neighborhoods. The couple married after Isaacs, in a panic having convinced herself that she was pregnant, implored her occasional boyfriend to marry her despite the fact that they’d not actually had a physical relationship. A year later, they had their first child; three years after that, in 1946, Malcolm. Not long after that the marriage disintegrated, in part due to the extended manipulation of Emily’s mother Rose, who was always dead set against the relationship; Peter left on the understanding that he would have no contact with his children as long as Emily was alive, an agreement which he honored, only meeting his son in 1989.

McLaren’s childhood was tumultuous despite the relative privilege of his upbringing. His mother and Rose got along poorly, and Emily was largely absent, leaving him to be raised by his stunningly eccentric grandmother, a theatrical raconteur who grew up helping her father sell off flawed diamonds by making up a variety of outlandish stories, and who claimed close friendship with Agatha Christie and to know the sexual secrets of tea magnate Sir Thomas Lipton. (This latter boast turned out to be broadly correct when, decades later, Lipton’s homosexuality was revealed, although Rose’s specific claim of procuring young men to masturbate Lipton during lunch breaks is rather less verifiable.)

After a string of odd jobs, McLaren found his way into the art school ecosystem during an unusual period in British life in which art schools outnumbered traditional universities by more than six to one. There, he was struck by his first lecture who extolled the virtues of William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement, and stressed the artistic value of failure. Here, at least, McLaren seems a middle class echo mirror of Moore, who absorbed a similar ethos from the Northampton Arts Lab, Art School having been precluded by his expulsion from school. (A stranger echo: McLaren recounts a powerful experience at the British Museum, sketching the stolen Parthenon statues, writing “for the first time I drew someone else’s art. I didn’t know who the artist was nor how this head came to be, but the life that poured ou tof it seemed to be something I could worship.” The subject: a horse pulling the chariot of Selene.)