Chapter Seven: Stomped Into Paste (A Brother To Dragons)

CW: rape, sexual assault, violence against women, transphobia, and homophobia. This chapter contains multiple NSFW images.

There is, however, another important sense in which Rorschach represents a myopia within Watchmen and, more broadly, Moore’s larger artistic vision. As mentioned, a crucial part of Rorschach’s psychology is his tortured relationship with sexuality. Sex is a major theme of both Watchmen and Moore’s career, and one that he has much of value to say about, but there is something unseemly about the directness with which Rorschach’s disgust with sex is pathologized, not least because it’s a character trait inherited from his underlying relationship with the apparently asexual Steve Ditko. More broadly, there is something oversimplified and unsatisfying in Moore’s approach to sexuality—a flaw intimately connected to his persistent inadequacy on the subject of sexual assault. This would be a relatively minor issue were it not for the awkward fact that the relationship between superheroes and sexuality is one of the comic’s major themes.

There is, however, another important sense in which Rorschach represents a myopia within Watchmen and, more broadly, Moore’s larger artistic vision. As mentioned, a crucial part of Rorschach’s psychology is his tortured relationship with sexuality. Sex is a major theme of both Watchmen and Moore’s career, and one that he has much of value to say about, but there is something unseemly about the directness with which Rorschach’s disgust with sex is pathologized, not least because it’s a character trait inherited from his underlying relationship with the apparently asexual Steve Ditko. More broadly, there is something oversimplified and unsatisfying in Moore’s approach to sexuality—a flaw intimately connected to his persistent inadequacy on the subject of sexual assault. This would be a relatively minor issue were it not for the awkward fact that the relationship between superheroes and sexuality is one of the comic’s major themes.

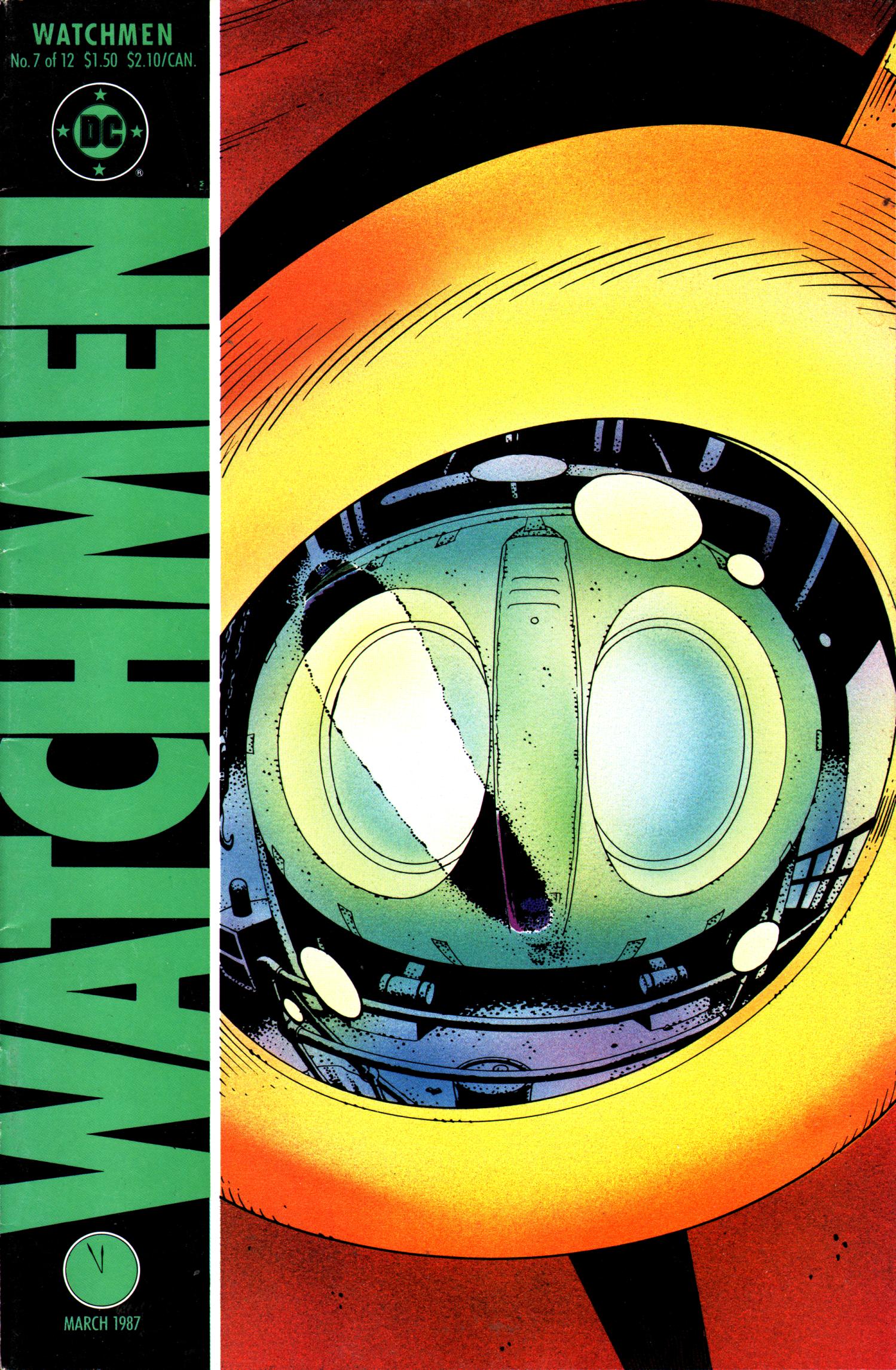

The theme of sex within Watchmen ignites in the seventh issue, “A Brother to Dragons,” which forms, along with “The Abyss Gazes Also,” a symmetrical axis at the center of the series. Watchmen can be divided into two types of issues: ensemble pieces that feature a large cross-section of the cast, and character-focused issues that provide backgrounds and meditations on individual heroes. The first half of the book alternates between these two types, with “At Midnight, All the Agents,” “The Judge of All the Earth,” and “Fearful Symmetry” jumping among multiple points of view while “Absent Friends,” “Watchmaker,” and “The Abyss Gazes Also” focus on the Comedian, Dr. Manhattan, and Rorschach respectively. The second half also alternates back and forth, but here it is the odd-numbered issues that are character-focused, looking at Ozymandias, Silk Spectre, and, in “A Brother To Dragons,” Night Owl.

The theme of sex within Watchmen ignites in the seventh issue, “A Brother to Dragons,” which forms, along with “The Abyss Gazes Also,” a symmetrical axis at the center of the series. Watchmen can be divided into two types of issues: ensemble pieces that feature a large cross-section of the cast, and character-focused issues that provide backgrounds and meditations on individual heroes. The first half of the book alternates between these two types, with “At Midnight, All the Agents,” “The Judge of All the Earth,” and “Fearful Symmetry” jumping among multiple points of view while “Absent Friends,” “Watchmaker,” and “The Abyss Gazes Also” focus on the Comedian, Dr. Manhattan, and Rorschach respectively. The second half also alternates back and forth, but here it is the odd-numbered issues that are character-focused, looking at Ozymandias, Silk Spectre, and, in “A Brother To Dragons,” Night Owl.

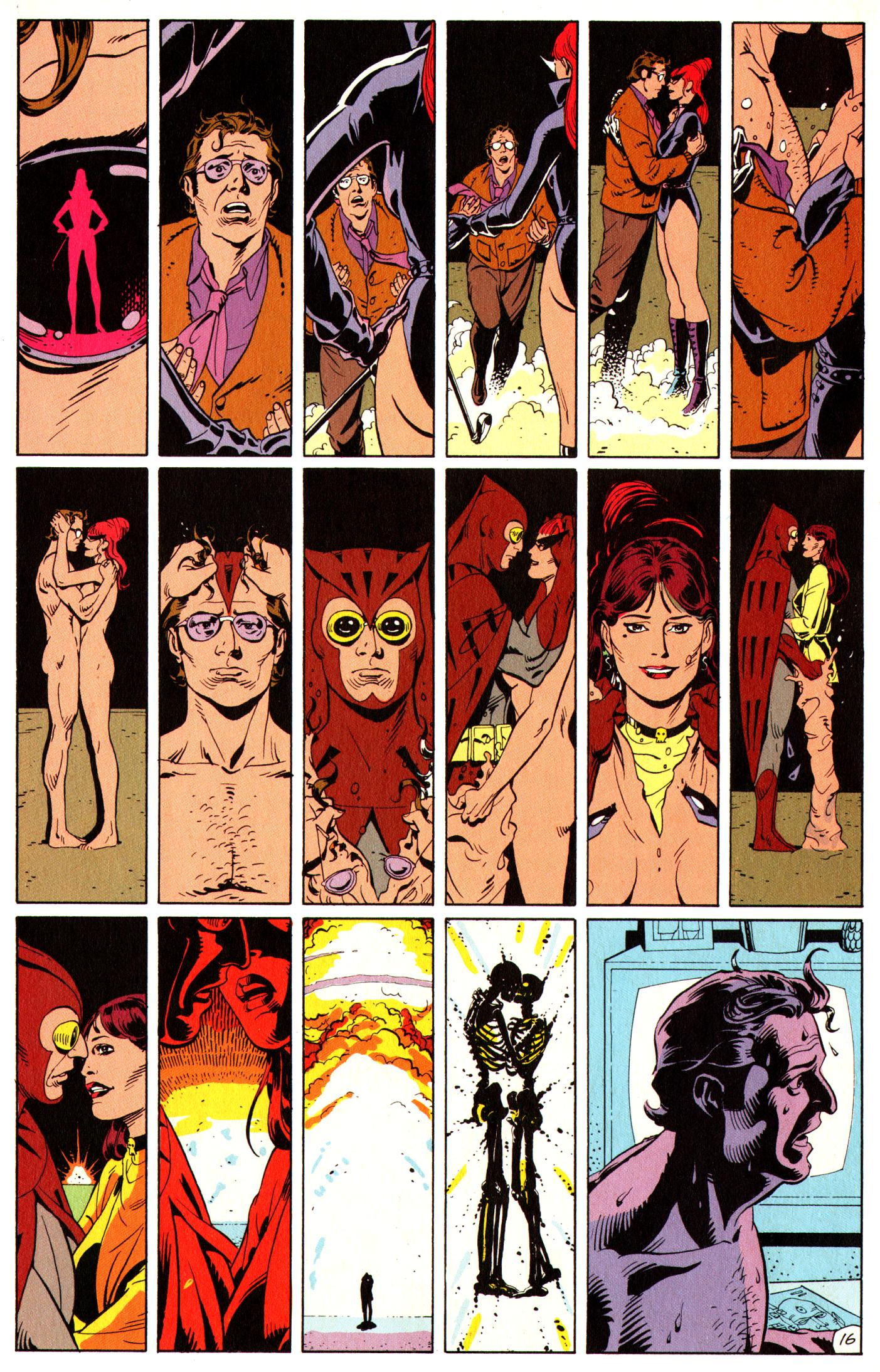

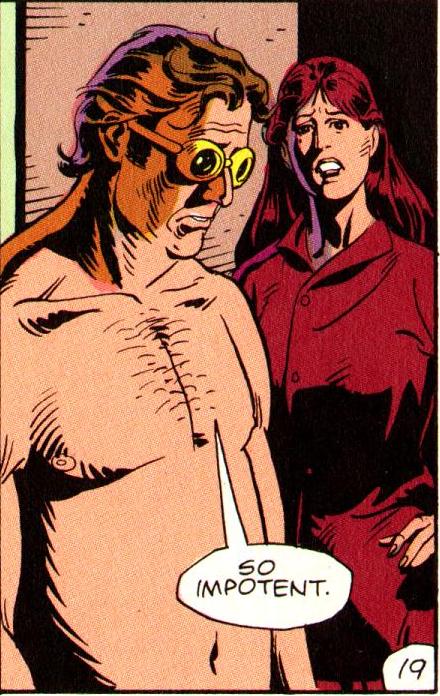

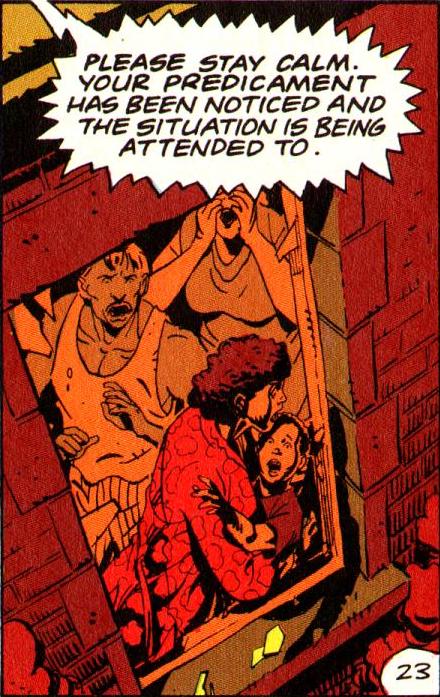

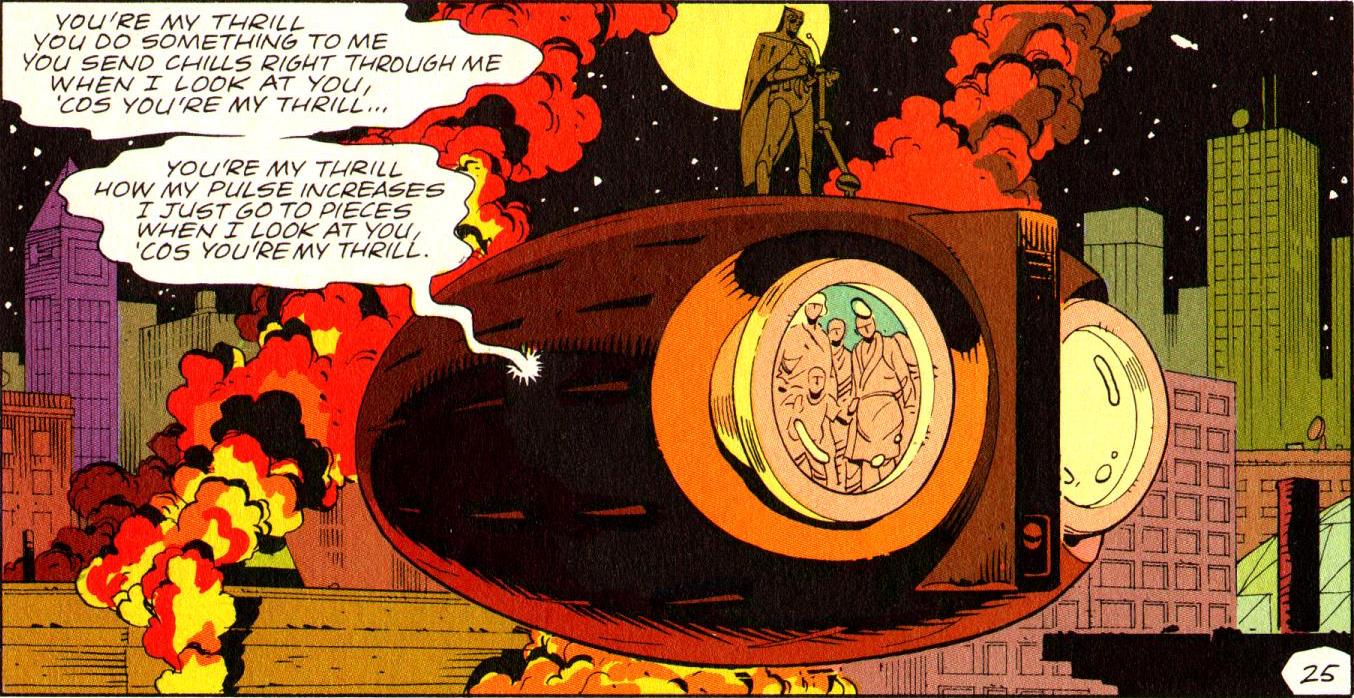

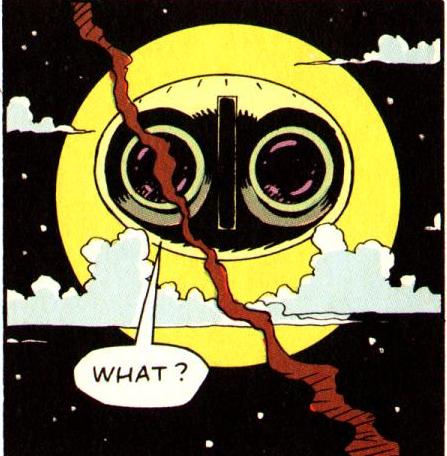

But structurally forcing the direct comparison to “The Abyss Gazes Also” does few (indeed no) favors to “A Brother To Dragons.” For all that “The Abyss Gazes Also” overplays its hand, it is at least a comic in which things happen in subtext, requiring the reader to work through the twin unreliable narrators of Malcolm Long and Rorschach. “A Brother to Dragons,” on the other hand, is aggressively straightforward, dropping its thematic points squarely into the dialogue to make absolutely sure nothing is missed. Its plot is simplistic and linear, with only one sequence of any significant formal complexity, and even that’s pretty up front about its meaning. Basically, Dan explains his backstory to Laurie as they meander around his basement. They go upstairs, watch some television, and have unsatisfying sex because Dan can’t get it up. Then Dan has a dream about being vaporized in an atomic blast, after which he and Laurie return to the basement and he talks about how the threat of looming nuclear war makes him feel impotent. They decide to go out for a bit of superheroics, rescue people from a tenement fire, and then have more successful sex, which is explicitly acknowledged to have been better because they did it in costume, after which Dan proposes breaking Rorschach out of prison in the first actual forward motion of the plot since the end of “Fearful Symmetry.” Even the backmatter is pretty drab – an essay by Dan about how much he likes birds.

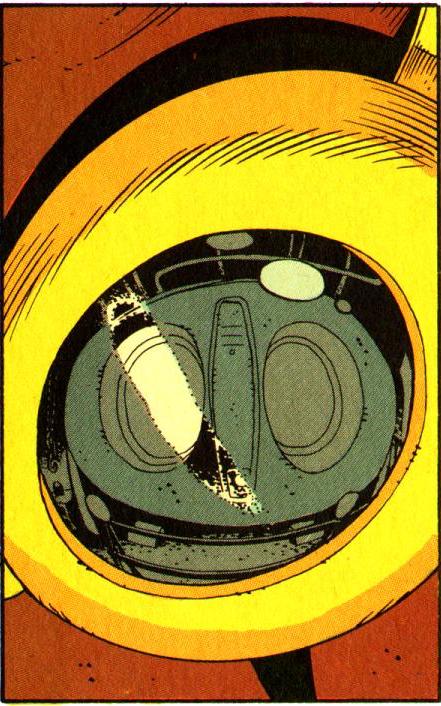

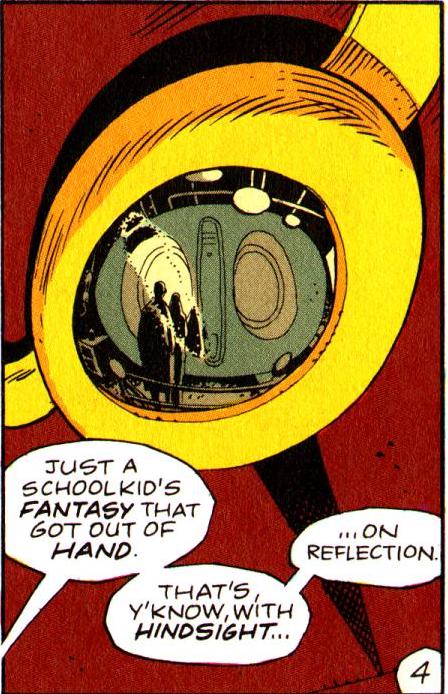

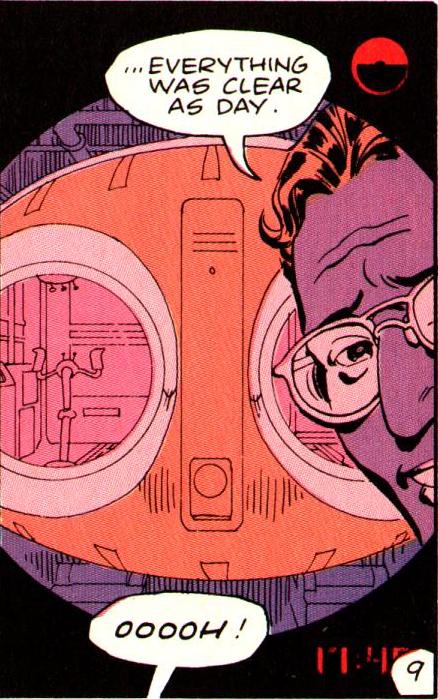

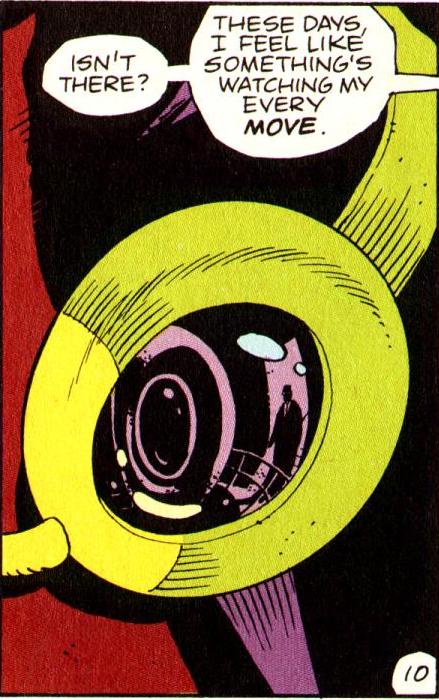

But at least some of this disparity can be accounted for by the different natures of what the two issues are doing. “The Abyss Gazes Also” seeks to complicate. Its endgame is an understanding of Rorschach as an aberration, defined precisely by the extent to which he cannot be comprehended and reckoned with. “A Brother To Dragons,” on the other hand, moves towards a moment of clarity, as evidenced by its repeated motif of Night Owl’s goggles, which appear in close-up on the cover with a single finger-mark traced over the left lens, removing a layer of dust so that they can be seen through clearly. And the point is reiterated throughout the issue. Dan gives Laurie the glasses to wear at one point while monologuing about how “no matter how black it got, when I looked through these goggles everything was clear as day,” with the final bit of the line in a panel from Laurie’s perspective as she gazes through them, exclaiming “ooooh!” Later, when he confesses his impotence, it’s in a panel of him naked except for his goggles, staring down towards his (unseen) flaccidity. And finally, when he admits that it was the costumes that made his sex with Laurie satisfying, it takes place in a close-up panel of the goggles, their naked bodies reflected in the lens.

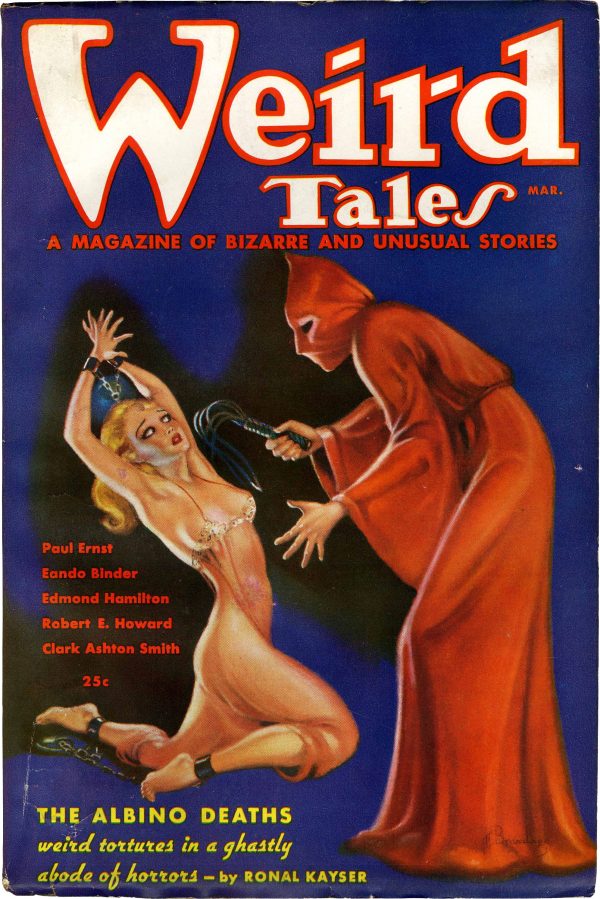

More to the point, this clarity is appropriate for the comic’s actual point. Moore is right to identify sex as an aspect of superheroes that is both obvious and repressed. This is rooted in their very origins as an evolution of pulp magazines. Newspaper and magazine distribution in New York City was a mob business, and the pulp companies thus often had ties to them. For instance, one of the early principals in DC Comics was Harry Donenfeld, who early in his publishing career had a sideline in helping future Luciano crime family boss Frank Costello smuggle Canadian liquor in amidst their regular imports of Canadian paper. In practice, this meant that the pulps were never far from the pornography business. And this showed in their presentation, where sexuality was routinely among the forms of luridness used to catch the eye. This included not just the usual array of heaving and scantily clad bosoms that one would expect from popular culture, but also things like Margaret Brundage’s body of work for Weird Tales, whose images of lithe damsels visibly enjoying their distress sizzled with a sexuality that had barely been repressed enough to avoid falling afoul of community standards of decency.

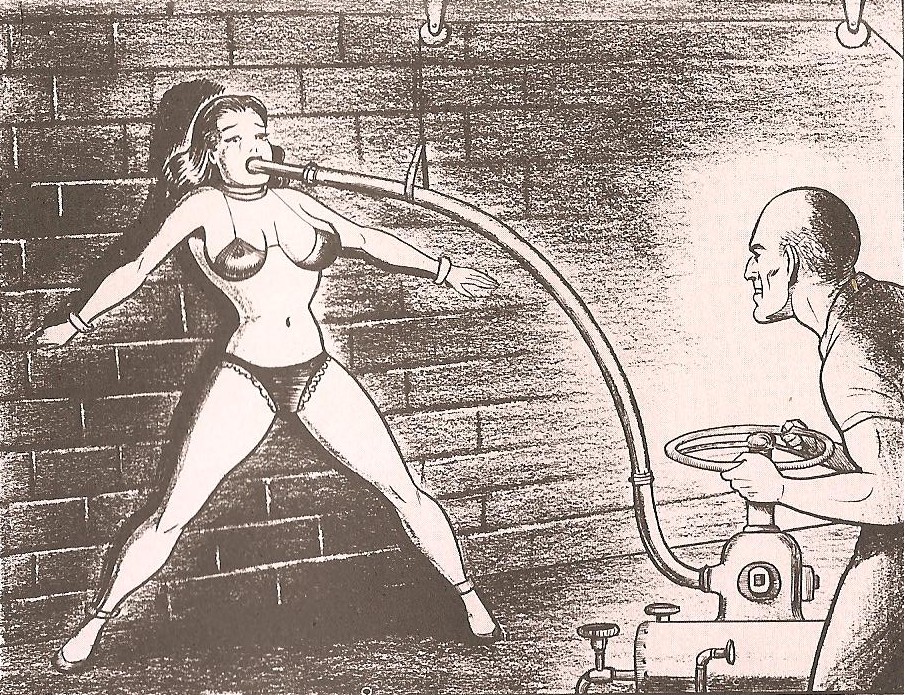

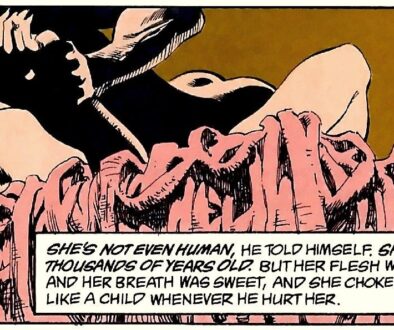

And as the pulps gave way to comic books, pornography was never far behind. After Superman co-creator Joe Shuster was effectively driven out of the industry for trying to sue DC Comics for control of Superman, for instance, he spent 1954 doing illustrations for Nights of Horror, a low-rent magazine full of grisly tales of rape and bondage, some of them intense enough to still horrify today. (The illustration of a topless woman being held by a man in an executioner’s hood while another man smears honey on her and covers her in fire ants is particularly unsettling.) Although Nights of Horror was an illustrated prose magazine more in line with the classic pulps than comics, Shuster’s art was a clear throwback to his work on Superman, with many of the characters clearly resembling the Superman cast. And Shuster was hardly the only comics artist to have a sideline in the erotic; even Steve Ditko had a period where he was inking the fetish art of his studio-mate Eric Stanton.

And yet for all the historical proximity of early comics and pornography, the most important early intermingling of sex and superheroes came from an entirely different direction. In 1941, DC turned to psychologist William Moulton Marston to create a superhero. Their reasoning in doing so was essentially defensive; Marston had done an interview for the women’s magazine Family Circle in which he argued that the comics medium was underutilized and had considerable untapped potential for social good. This caught the eye of DC publisher Max Gaines, who hired Marston with a specific goal of providing a level of respectability for the publisher. But Gaines had failed to fully appreciate just how odd his new hire was. The Family Circle interview that had caught his eye was written by Olive Richard, who was in fact Olive Byrne, Marston’s longtime research assistant and part of a polyamorous triad with him and his wife Elizabeth. The piece was a naked attempt to get Gaines’s attention, to the point of praising him by name, which is generally in keeping with Marston’s approach to life. Although a credentialed psychologist, he was in practice a huckster and a charlatan of the most glorious sort, spinning out grandiose project after grandiose project in amidst sprawling and overly ambitious theories of human behavior.

And yet for all the historical proximity of early comics and pornography, the most important early intermingling of sex and superheroes came from an entirely different direction. In 1941, DC turned to psychologist William Moulton Marston to create a superhero. Their reasoning in doing so was essentially defensive; Marston had done an interview for the women’s magazine Family Circle in which he argued that the comics medium was underutilized and had considerable untapped potential for social good. This caught the eye of DC publisher Max Gaines, who hired Marston with a specific goal of providing a level of respectability for the publisher. But Gaines had failed to fully appreciate just how odd his new hire was. The Family Circle interview that had caught his eye was written by Olive Richard, who was in fact Olive Byrne, Marston’s longtime research assistant and part of a polyamorous triad with him and his wife Elizabeth. The piece was a naked attempt to get Gaines’s attention, to the point of praising him by name, which is generally in keeping with Marston’s approach to life. Although a credentialed psychologist, he was in practice a huckster and a charlatan of the most glorious sort, spinning out grandiose project after grandiose project in amidst sprawling and overly ambitious theories of human behavior.

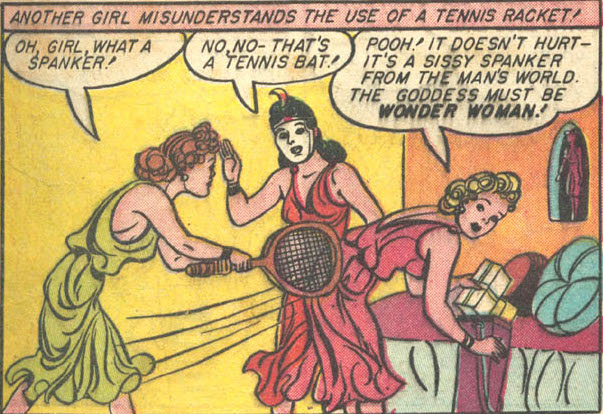

The result was Wonder Woman, who in her earliest days offered a heady cocktail of utopianism and sexuality. On the one hand, the character was designed out of Marston’s belief that unchecked and aggressive masculinity had led to two world wars, and that the only plausible salvation for humanity was for men to be ruled over by women. This was in line with his psychological theories, which focused explicitly on the idea of willing submission and nonviolent authority. But even without knowing he was in a queer polyamorous triad, there’s clearly a sexual dimension here that’s visible in Marston’s enthusiastic declaration that if you give men “an alluring woman stronger than themselves to submit to… they’ll be proud to become her willing slaves!” And this is clearly visible in the comics, which are chock full of urgent discussions of the need to submit to loving authority and, for that matter, bondage and spanking, all of it presented with a wide-eyed and earnest thrill that stands in stark and shocking contrast to the grimly macabre tone of Shuster’s fetish art.

When it came time to have a moral panic about comic books in the 1950s, however, it was not their incipient sexuality that proved troublesome; rather it was their violence. Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent, which is generally viewed as kicking off the moral panic, devotes only a twenty-three page chapter to “comic books and the psychosexual development of children,” framing the bulk of its objections in terms of juvenile delinquency. And that chapter, despite its inventively alarmist title “I Want to Be a Sex Maniac!”, is surprisingly even-handed in its take on sex, acknowledging up front the different opinions on how sex education should be conducted, and making nuanced observations like that “masturbation is harmless enough. But when accompanied by unhealthy—especially sado-masochistic-fantasies it may become a serious factor in the maladjustment of children.” And this careful moderation was not unusual—Gershon Legman, another psychologist who had condemned comics in his 1949 book Love and Death and who had appeared with Wertham at a 1948 symposium entitled “The Psychopathology of Comics,” notes, “children, we are told—and told it often—are naturally cruel. They tear the wings off flies. So they do. Children are also naturally sexual. They examine each other’s genitals, and masturbate. Why is this worse? Why is sadism in children ‘innocuous ferocity’ while masturbation is a sin & a shame?” And this is consistent with his larger career—these days he’s best known for a massive compendium and exegesis of dirty jokes. Nor were Legman and Wertham wrong per se—their tone may be exceedingly alarmist, but the fact of the matter is that comic books of the time were full of sexualized violence against women that differed from Siegel’s Nights of Horror work in degree alone.

When it came time to have a moral panic about comic books in the 1950s, however, it was not their incipient sexuality that proved troublesome; rather it was their violence. Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent, which is generally viewed as kicking off the moral panic, devotes only a twenty-three page chapter to “comic books and the psychosexual development of children,” framing the bulk of its objections in terms of juvenile delinquency. And that chapter, despite its inventively alarmist title “I Want to Be a Sex Maniac!”, is surprisingly even-handed in its take on sex, acknowledging up front the different opinions on how sex education should be conducted, and making nuanced observations like that “masturbation is harmless enough. But when accompanied by unhealthy—especially sado-masochistic-fantasies it may become a serious factor in the maladjustment of children.” And this careful moderation was not unusual—Gershon Legman, another psychologist who had condemned comics in his 1949 book Love and Death and who had appeared with Wertham at a 1948 symposium entitled “The Psychopathology of Comics,” notes, “children, we are told—and told it often—are naturally cruel. They tear the wings off flies. So they do. Children are also naturally sexual. They examine each other’s genitals, and masturbate. Why is this worse? Why is sadism in children ‘innocuous ferocity’ while masturbation is a sin & a shame?” And this is consistent with his larger career—these days he’s best known for a massive compendium and exegesis of dirty jokes. Nor were Legman and Wertham wrong per se—their tone may be exceedingly alarmist, but the fact of the matter is that comic books of the time were full of sexualized violence against women that differed from Siegel’s Nights of Horror work in degree alone.

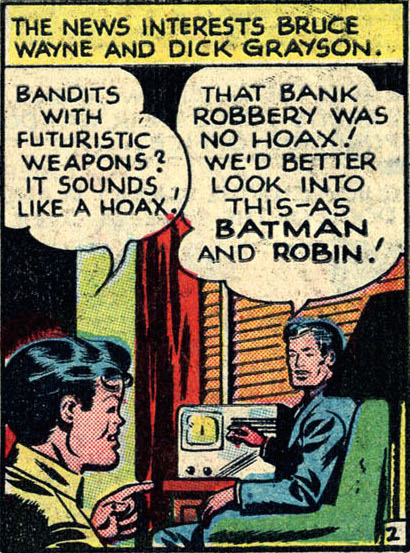

Lest one start to think that Legman and Wertham are basically allies of Moore, who has made similar arguments throughout his career, one ought remember that these are not being offered as critiques or suggestions on how to do better, but as justifications for censorship; Wertham went so far as to testify before Congress in 1954 about the evils of comic books. But even beyond their proposed remedies, Wertham and Legman’s post-Freudian take on sexuality departs vividly from Moore’s, most obviously in their vivid disdain for homosexuality. Wertham goes on for five pages about comic books reinforcing homosexual fantasies, most famously fixating on Batman and Robin, who he describes as “like a wish dream of two homosexuals living together.” Legman is more vivid, talking about “the two comic-book companies staffed entirely by homosexuals and operating out of our most phalliform skyscraper” (it is not clear what companies or indeed skyscraper Legman is talking about) and “the obvious faggotry of men kissing one another and saying ‘I love you’ and then flying off through space against orgasm backgrounds of red and purple.”

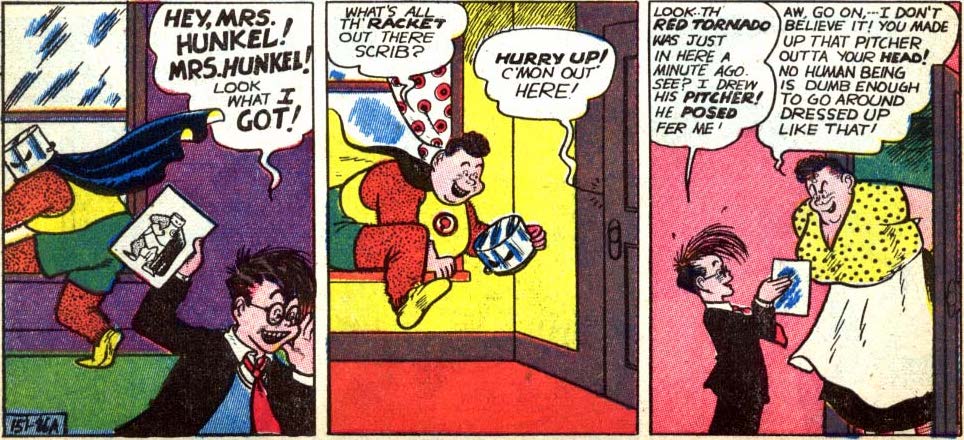

In truth, for all that comics teemed with barely repressed sexuality, queer content was at something of a premium. Marston’s Wonder Woman, which got consistent input from his partners, had a consistent and deliberate sapphic tone until his death in 1947, but beyond that the gay content Wertham and Legman were so frothingly paranoid about was desperately thin. The bulk of it consisted of gender play, with characters such as DC’s Red Tornado, whose secret identity was a plus-sized middle aged housewife named Ma Hunkel, and Quality Comics’s Madame Fatal, who was in reality Richard Stanton. In both cases, the secret identities were clearly queer-coded. While both Ma Hunkel and Richard Stanton were nominally married, Hunkel was a short-haired, muscular loudmouth of a woman while Stanton was a dapper Wall Street financier turned theater actor.

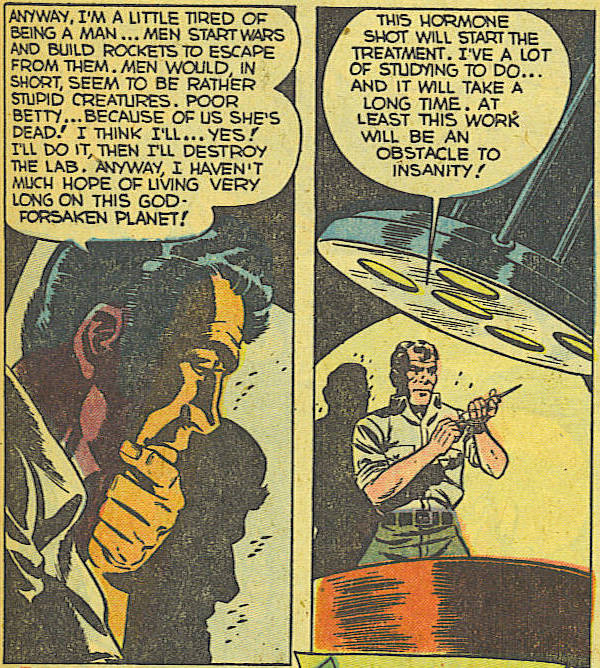

Perhaps the most remarkable queer comic of the period, however, is a 1953 story in Charlton’s Space Adventures entitled “Transformation,” and described on the cover as “the hard-hitting story of scientists’ most recent revelation.” Published just a few months after the news of Christine Jorgensen’s surgical transition reached newspapers, the eight-page story (drawn by Dick Giordano, who would go on to be Executive Editor of DC Comics during the period Moore worked there and whose hardline anti-creators’ rights stance would be part of what drove Moore away from the company) tells of Doctor Lars Kranston, who attempts to flee the impending start of World War III by taking a rocket to Mars with a couple of other scientists and, after she begs to join them, Kranston’s secretary and “sweetheart” Betty. The rocket crashes, with Kranston and Betty the only survivors, each of them unaware of the other. Kranston proceeds to investigate the wrecked rocket and another one of the scientists’ notes on sex conversion. After a monologue proclaiming, “I’m a little tired of being a man… men start wars and build rockets to escape from them. Men would, in short, seem to be rather stupid creatures,” Kranston draws up an injection of hormones and begins the process of transition. The resolution is grimly sensationalist, with Betty and Kranston reuniting and Betty reacting with horror and revulsion that her love interest is now a woman, but the story is on the whole a surprisingly frank portrayal of gender dysphoria.

Just one year later, however, Wertham published Seduction of the Innocent and the Comics Code was established, with its prohibitions on even hinting at “sexual abnormalities” and “sex perversion” and its demand that “the treatment of live-romance stories shall emphasize the value of the home and the sanctity of marriage.” And with that the possibility represented by these queer comics slammed shut. The immediate aftermath of the Code was a vast and pathological de-sexualizing of comics. Most famously, the gay overtones of Batman and Robin were eliminated by hastily introducing Batwoman and Bat-Girl to serve as beards for them. But the aggressive sexlessness of post-Code comics went beyond over-protesting the characters’ heterosexuality; Catwoman, for instance, simply vanished from Batman comics for twelve years due to the sexualized elements of her character.

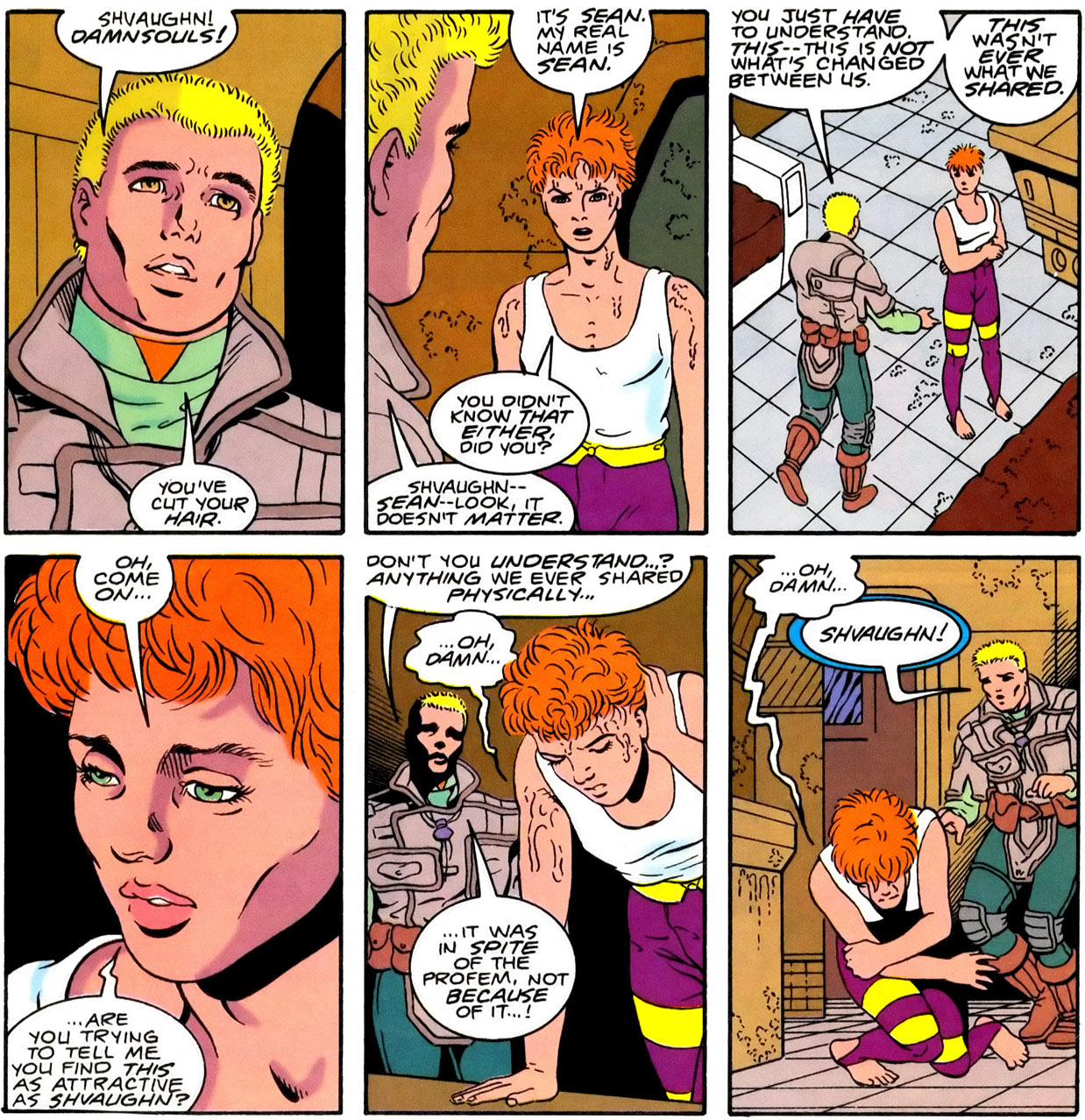

On the rare occasions over the next few decades when queer content began to creep into comics, there were similar efforts to shut them down. For instance, after Legion of Superheroes fans started to seize on the fact that Element Lad professed to be “out of my element when it comes to romancing girls,” and who was conspicuous as the only member of the team without a love interest. Though DC allowed this to play out for some fifteen years, eventually the quantity of fanzines drawing the obvious conclusion drove them to shoehorn in a straight romance for the character, although a 90s story (after a 1989 revision of the Comics Code that dropped the ban on homosexuality) eventually had another girlfriend of his turn out to be transgender but recently unable to afford the drugs that maintain her female form, a problem Element Lad declared himself unbothered by. (This is something of a double edged sword in terms of queerness, as the story clearly views her female identity as illegitimate and her male identity as her “real” one, to the point of treating her transition as an analogy for drug addiction.)

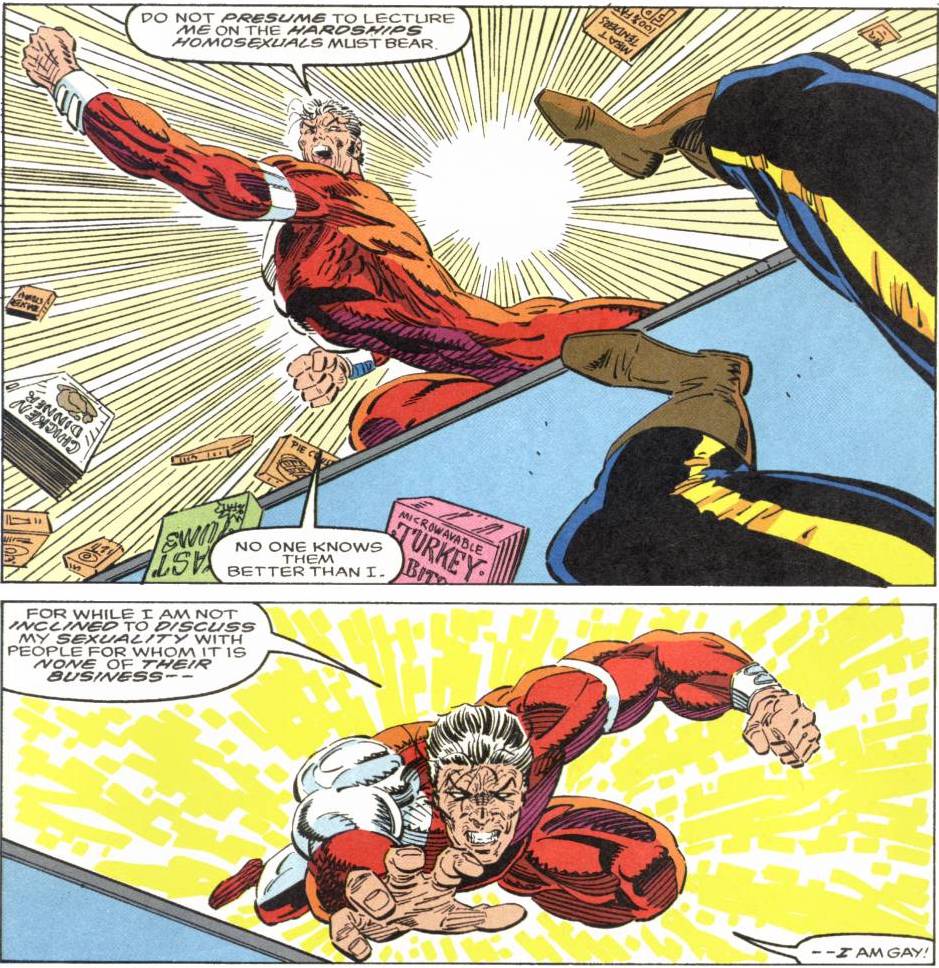

Over at Marvel, meanwhile, queer-coded characters were having only a slightly better time of things. When John Byrne was asked to expand Alpha Flight, a throwaway team of Canadian superheroes he’d co-created with Chris Claremont to fight the X-Men in one of those standard issue superhero misunderstandings, into an ongoing series, he decided that one of the characters should be gay. In his telling, after rejecting the other options for a variety of reasons including that making the giant fur-covered Sasquatch gay would be “too damn scary” and that making any of the female characters gay was “something people tended to associate (rightly or wrongly) with Claremont books” (more about which later), he settled on the French-Canadian Northstar. All of this, however, was happening in 1983, firmly in the period where Code-approved comics could not depict homosexuality, and so Northstar remained merely queer-coded, although plenty of people picked up on the subtext, and eventually in 1992 Alpha Flight writer Scott Lobdell was allowed to have him come out, which he did in the midst of beating the tar out of another superhero, Major Mapleleaf, delivering the unfortunately memorable monologue: “Do not presume to lecture me on the hardships homosexuals must bear. No one knows them better than I. For while I am not inclined to discuss my sexuality with people for whom it is none of their business, I am gay! Be that as it may, AIDS is not a disease restricted to homosexuals as much as it seems at times the rest of the world wishes that were so!”

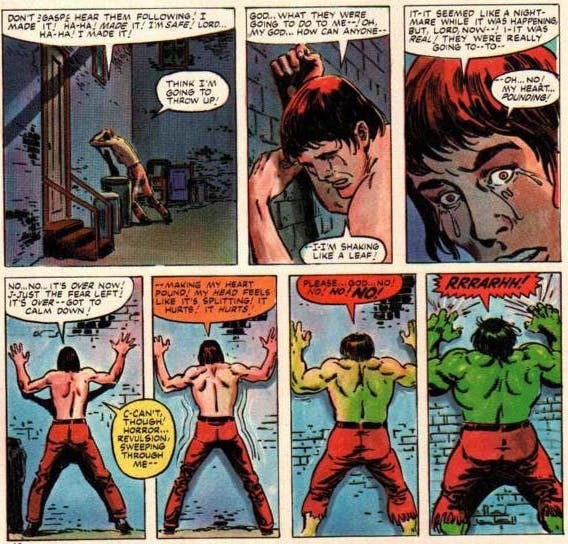

Although the Comics Code would have prevented explicit acknowledgment of Northstar’s homosexuality anyway, Byrne notes that his hands were further tied by Marvel editor-in-chief Jim Shooter, who Byrne specifically blamers for forbidding him from mentioning it explicitly. Certainly Shooter had prior form in terms of homophobia, having penned a 1980 story in Rampaging Hulk, an up-market Hulk comic in magazine format that wasn’t submitted for Code approval, in which Bruce Banner is nearly raped by a pair of men in the showers of his local YMCA. Even aside from the ways his attackers are grotesque stereotypes, the story has clear problems, with, bizarrely, Banner being too scared of the possibility of rape to transform into the Hulk, only shifting after he’s escaped, when the transformation is explicitly credited to the “horror… revulsion, sweeping through me.”

Where queer content found itself completely obliterated by the Comics Code, heterosexual content was generally able to skate through on thinly veiled innuendo. A classic example comes from a 1968 issue of Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. by Jim Steranko. In one scene, Fury and a woman are lounging around in his apartment and eventually end up having sex, which Steranko depicted with a fairly tame and zoomed out shot of the two of them embracing. The Code objected, however, and so the panel was replaced by a close-up of Nick Fury’s gun in its holster, a change that inexplicably sailed through despite being, once one understands the implication, even more suggestive than Steranko’s original.

While this sort of petty censorship is obviously both annoying and mockable, there’s still a basic level of representability to heterosexuality available. And for all the Comic Code’s insistence on “the value of the home and the sanctity of marriage”or its declaration that “rape shall never be shown or suggested” and “females shall be drawn realistically without undue emphasis on any physical quality,” the reality was that a male-dominated industry with a license to depict straight sexuality was always going to trend back towards the violent misogyny that Legman and Wertham decried.

Examples of the cases where it repeatedly did abound. John Byrne, for instance, may have tried to provide tacit queer representation with Northstar, but he was also the writer of a two-issue Superman arc in which Superman and Big Barda are kidnapped by a villain named Sleez, mind-controlled, and forced to act in pornographic movies. The story is from 1987, just two years before the Comics Code was finally revised to remove the most onerous restrictions on sex and sexuality, and the sense of loosening restrictions is palpable—Byrne never comes out and says what the videos Superman and Barda are being forced to record are, but it’s blatantly obvious, as is the fact that the streets of Suicide Slum where Barda and Superman are taken by Sleez are full of pimps and prostitutes. It’s a bewilderingly sordid comic, offering nothing save for the leering transgressive pleasure of making Superman do porn. (Byrne, for his part, accuses Moore of having “perverted pretty much everything the superhero genre is all about” in Watchmen.)

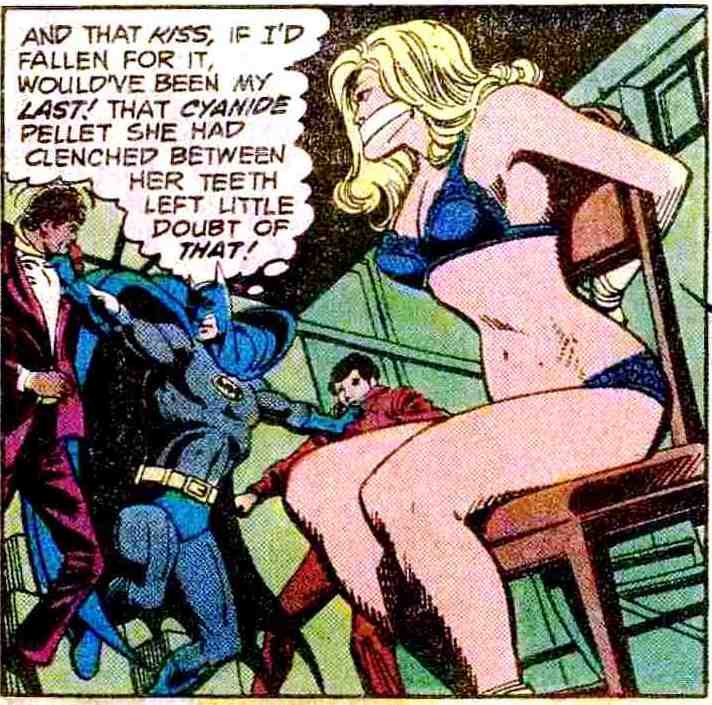

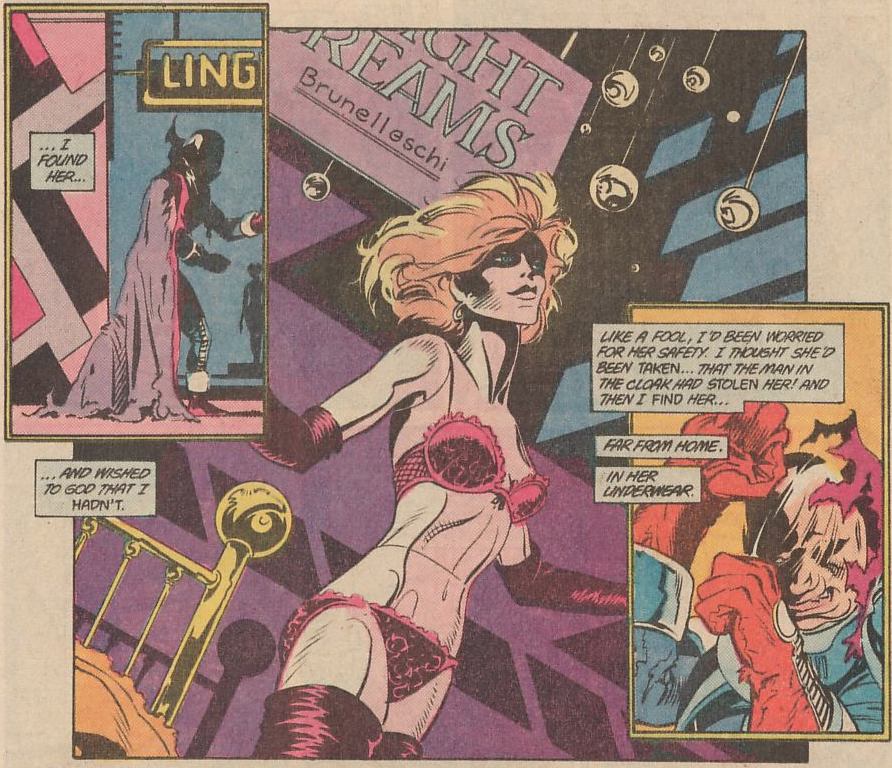

Another example, notable if only because Moore called it out by name in his “Invisible Girls and Phantom Ladies” essay, is Michael Fleisher, where he describes with dripping contempt “a particularly charming Michael Fleischer [sic] story that appeared in DC’s The Brave and the Bold during which the usually quite capable Black Canary spent almost the entire issue tied to a chair wearing only her underwear, while the villain of the piece delivered such memorable and sensitive dialogue as ‘you squirm so prettily, my dear.’” As is often the case with Moore, he’s over-egging the custard; Black Canary is only shown tied up for the final three pages of the comic (although she’s kidnapped for more of it, this is kept secret from the reader for most of that time as an imposter adventures with Batman), and the dialogue Moore quotes never actually appears—the closest is “now, now, my dear! There’s really no call for you to protest your captivity so vociferously!” Still, Moore is not wrong in the broad strokes, especially when it comes to the ending, in which Black Canary proclaims that “liberated ladies aren’t supposed to say things like this, Batman, but you know what? You’re my hero” as she kisses him. Certainly the art by Dick Giordano and Terry Austin, which is positively lascivious when it comes to depicting the underwear-clad Black Canary, supports Moore’s claim that the comic represents a case of “dishing up evil, sordid little adult fantasies as suitable fare for the growing minds of healthy boys and girls.”

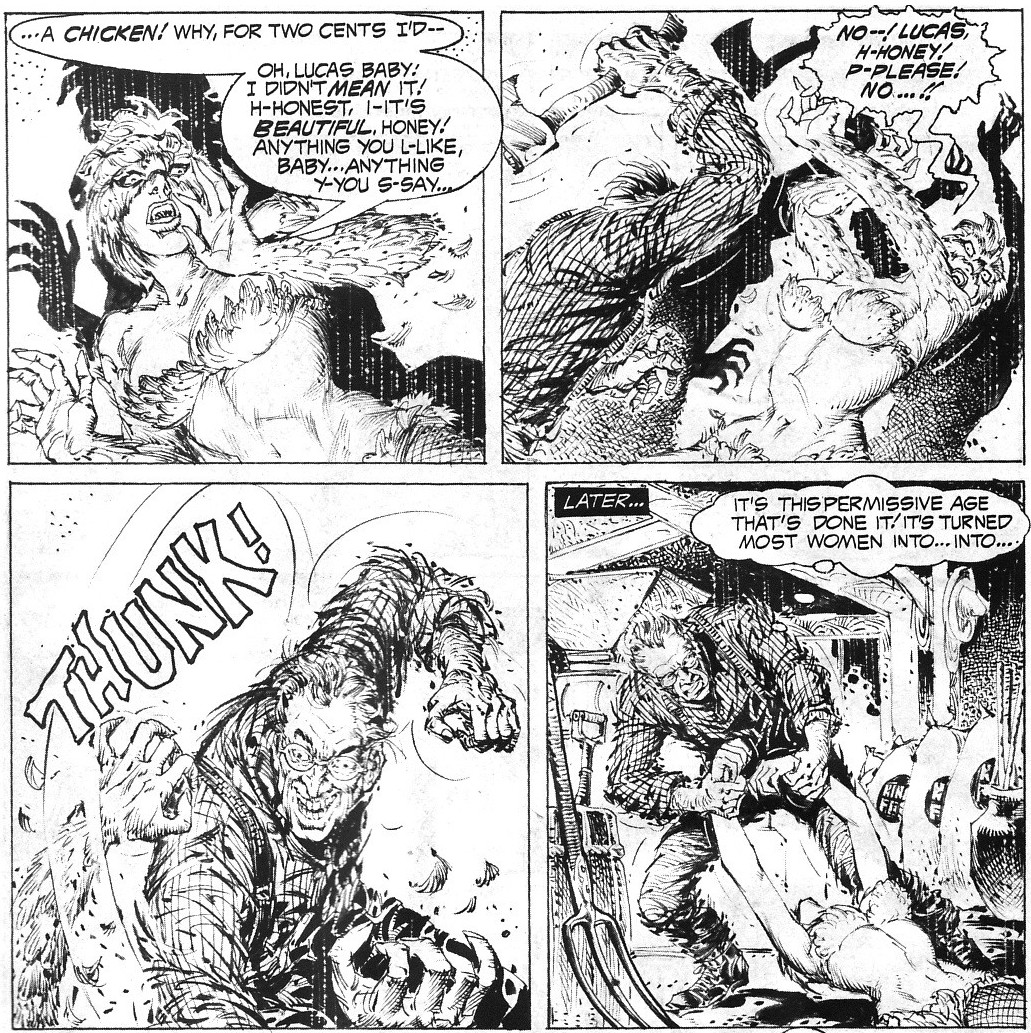

Certainly Fleisher has form in this department. A year before the Brave and the Bold issue he published his first novel, Chasing Hairy, marketed as a “novel of sexual terror,” and featuring a plot in which two deeply misogynistic men force a female hitchhiker to perform a variety of sex acts before dousing her with gasoline and setting her on fire in the backseat of a car, with the novel’s final lines describing how as “fragments of the flaming automobile hurtled into the air, they formed a flaming, spinning jigsaw puzzle high in the air, ragged chunks of human flesh rose skyward with them, arms and thighs and entrails tumbled wildly through the air. And then the gruesome stuff descended, clattering on the tops of the picnic tables, drenching the ground around them in a rainfall of gore.” It’s not a surprise, then, that Harlan Ellison took this book as an occasion to descrive Fleisher as “bugfuck” and “certifiable,” in an interview with The Comics Journal, leading Fleisher to sue him and the magazine for libel. But Chasing Hairy is basically par for the course for Fleisher—he’s also the author of the (non-Code) story “Night of the Chicken,” which he lists as one of his three favorite stories, and which opens with a farmer hiring a prostitute, dressing her in a chicken costume, and then hacking her to pieces with an axe while reflecting, “it’s this permissive age that’s done it! It’s turned most women into… into…” and then, as he stuffs the body into a sack of chicken feed, “maybe if they’d listen to their parents once in a while… and stop worshippin’ all them hippies they see on TV… they’d turn into decent women instead of… instead of…” And even in his superhero work, he’s best known for writing The Spectre, where he developed a firm reputation for comics full of luridly violent punishments, whether overtly sexual or not.

_(d)(w)_(hiddenleaf)__0044.jpg)

It would of course be grotesquely reductive to suggest that someone who routinely writes violent stories is in some sense prone to violence in their own right; were one to do so, all of the major figures in the War would come under some pretty intense scrutiny. But the point isn’t whether Fleisher, Byrne, or anyone else is actually doing anything bad; it’s not even moral judgment per se. The point is simply that these comics do, in fact, represent sexual fantasies and are providing some measure of gratification for their writers. Fleisher freely admits that “I have a violent imagination,” and that “there’s a lot of antagonism between the sexes… I am not free of those feelings. I try in my life to behave as well as I can. In my stories I give free expression of those feelings.” And while he describes Chasing Hairy as “serious fiction” that attempts to get the reader to identify with the violent and misogynistic men and then gradually bring them to the point of their violent murder at the end, it’s clearly of a type, with any intended revulsion (if indeed Fleisher’s description of a rain of human flesh can be described as showing revulsion and not just childish sniggering) at the conclusion serving as the other side of the coin of the earlier attraction.

Not everyone’s comic book sexuality is quite so sordid, however. While there are countless writers like John Byrne or Michael Fleisher who used comics to satisfy gruesome fantasies of violent misogyny, there are also writers like Marston who explored sexualities that, while still troubled by sexism (a pedestal’s no different from a cage if you can’t get off it), are at least unusual and visionary in odd and compelling ways. And while this latter category is depressingly smaller than the former, it’s by no means confined to Marston. Consider, for instance, Chris Claremont, whose staggering sixteen-year run writing Uncanny X-Men, despite not being governed by any expressly sexual agenda in the way Marston did, was simply such a massively long stretch of time spent with the same pool of characters that it is all but inevitable that it would provide at least some level of window into his psyche.

Thankfully, it’s an interesting psyche. Claremont is unlike Marston in that his obsessions do not organize neatly into a moral program. Nevertheless, there are recurrent themes. Some, such as his curious fascination with age-regressing characters (Uncanny X-Men #110-11, Uncanny X-Men Annual #10, Storm in an extended early 90s plotline) or his more general tendency to depict extreme and grotesque body alteration (Uncanny X-Men #190, along with countless plots involving Mojo or Masque) are mostly just interesting without necessarily having wider political implications, or, when they do, failing to be much livelier than Byrne or Fleisher’s misogyny.

_132-05.jpg)

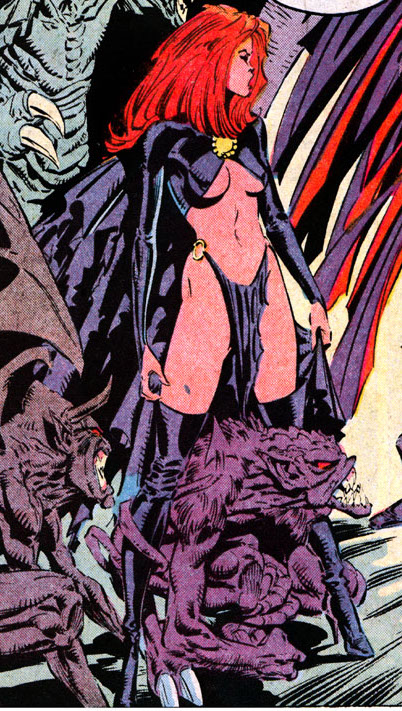

More interesting is the repeated motif of enormously powerful women becoming evil dominatrixes. The most obvious and classic example of this is the famed Dark Phoenix Saga, in which Jean Grey first becomes incredibly powerful following her merging with a cosmic entity, the Phoenix Force, and then goes mad, becomes evil, commits genocide, and gets killed. The sexual element of this is unmistakable—the instigating event in Jean’s corruption is her manipulation by Jason Wyngarde of the heavily BDSM-inflected Hellfire Club. Immediately before her subversion she has sex atop a remote mesa with her boyfriend Scott Summers, aka Cyclops, while psychically holding back the force of his normally uncontrollable optic blasts, a power typically used as a metaphor both for male puissance and repression. As they embrace, Scott mentally frets, “I don’t believe it! My eyes—how can Jean hold back all that power?!” Five pages later she’s in a leather corset and knee-high boots blasting him on Wyngarde’s behest.

_132-10.jpg)

Two issues later, when she recovers from the psychic manipulation (which is framed explicitly as a sexual violation—Jean rages at him that “you came to me when I was vulnerable. You filled the emotional void within me. You made me trust you—perhaps even love you—and all the while you were using me!” and then talks about how his manipulations were tailored “to fit my most private fantasies—the repressed, dark side of my soul.” And when her Phoenix powers are unleashed the effects are both explicitly psychedelic (“in the blink of an eye, Mastermind finds himself in touch with the universe—his brain flooded with all the myriad, absolute, contradictory truths of existence”) and blatantly orgasmic (“the obsidian flames burn brighter withiun her, and, in the distance, she hears music—a symphony of power long-sought and well-remembered. Transfixed by an unhuman [sic] joy, her burning soul spreads its wings and soars towards a destiny that will no longer be denied” and, later, “she reels under the impact of more sensations than she has names for… as her song of power builds to its inevitable crescendo.”).

Accounts of exactly what happened surrounding the resolution of the Dark Phoenix Saga are disputed, and several of the leading figures in the drama are notoriously unreliable narrators. The original intent was that Jean would lose her powers and would presumably return as a villain at some future date. But after Uncanny X-Men #137, the planned resolution of the arc, was already pencilled Marvel editor-in-chief Jim Shooter decided that he objected to this, viewing Phoenix as irredeemable following a moment in issue #135 in which she incinerated a solar system that contained an inhabited planet, resulting in the death of five billion people. This flourish, apparently added by John Byrne, who found Claremont’s plotted idea of destroying a single Shi’ar battlecruiser unsatisfying, resulted in an editorial mandate to kill Jean off entirely, which was accomplished in a hasty rewrite of #137 to have her commit suicide while momentarily in control of her powers in order to keep herself from killing again, vaporizing herself in front of Cyclops. This results in a desperately unsatisfying overall narrative: Jean Grey is sexually violated, is pushed into an erotically charged rage by it, and then commits editorially mandated suicide to resolve the matter.

And so Claremont proceeded to semi-obsessively revisit the setup through his later career, seemingly trying to do it right. His first effort came with Madelyne Pryor, a new love interest for Scott Summers who was a dead ringer for Jean Grey. Claremont’s original plan was to have Cyclops move on in a healthy manner, accepting that despite the physical similarity Madeline and Jean are different people, a plan he carried out in a 1983 story in which Mastermind returned and tried to drive Scott mad by convincing him that Madeline was Dark Phoenix, a story that ended with Scott and Madeline getting married. But in 1986 an editorial decision to revive the original X-Men team, Jean Grey included, in a new book to be called X-Factor necessitated another change of plans. This posed a significant problem, as it required Cyclops to abandon his wife and kid and go back to his ex-girlfriend, which, as Claremont pointed out, rather made him into an asshole. And so an elaborate retcon was enacted in which Madeline turned out to be a clone of Jean Grey created by Mr. Sinister, was possessed by demons, and became a leather-clad evil dominatrix who was then killed off.

Claremont would revisit the setup throughout his time writing the X-Men—variations appeared with Psylocke, Magik, and Karma, for instance. None of these ever quite work, of course; the foundations are too rotten. Claremont’s erotic terror at the incandescent rage of his post-traumatic women ultimately prevents him from quite reaching a satisfying form of reparation for the characters, at least within the confines of the superpowered soap opera genre he pioneered. Certainly it didn’t help that the comics were overwhelmingly being created by heterosexual men, which exacerbated the degree to which the women were denied a path that wasn’t objectifying—it’s telling that the closest thing to a satisfying resolution to any of these plots that Claremont manages is an exchange between Magik and Magneto in New Mutants #52 in which they bond over the irresolvable nature of their relationships to trauma, which is to say when he introduces a post-traumatic male figure to the narrative. But equally, it is not as though the introduction of women’s creative perspectives is a panacea—after all, the Madeline Pryor arc happened under the editorship of Louise Simonson, who was also responsible for a graceless effort to “fix” Magik by simply retconning all of her abuse out of existence.

Claremont would revisit the setup throughout his time writing the X-Men—variations appeared with Psylocke, Magik, and Karma, for instance. None of these ever quite work, of course; the foundations are too rotten. Claremont’s erotic terror at the incandescent rage of his post-traumatic women ultimately prevents him from quite reaching a satisfying form of reparation for the characters, at least within the confines of the superpowered soap opera genre he pioneered. Certainly it didn’t help that the comics were overwhelmingly being created by heterosexual men, which exacerbated the degree to which the women were denied a path that wasn’t objectifying—it’s telling that the closest thing to a satisfying resolution to any of these plots that Claremont manages is an exchange between Magik and Magneto in New Mutants #52 in which they bond over the irresolvable nature of their relationships to trauma, which is to say when he introduces a post-traumatic male figure to the narrative. But equally, it is not as though the introduction of women’s creative perspectives is a panacea—after all, the Madeline Pryor arc happened under the editorship of Louise Simonson, who was also responsible for a graceless effort to “fix” Magik by simply retconning all of her abuse out of existence.

Ultimately, Moore’s hypothesis—that the underlying problem with all of this is just the repression and censorship of sexuality in superhero comics—is credible. Claremont’s work, like Marston’s before him, is clearly elevated by the visionary sexuality that bubbles beneath the surface. But it’s also limited by the opacity of that surface, which serves simultaneously to empower people like Byrne and Fleisher to hide their ugly fantasies and prevent people like Claremont or anyone who might want to write about queer issues from being able to fully explore the topic.

Ironically, perhaps the best example of an alternative to all of this comes in Grant Morrison. For all that breaking into comics after him was a curse, there is no question that Morrison benefitted from entering an industry in which Moore had already helped create spaces where he could work without as many content restrictions, and had helped erode the power of the Comics Code, which was revised in 1989, the year after Morrison’s Animal Man ran began at DC, to remove the most onerous restrictions in favor of a bland “scenes and dialogue involving adult relationships will be presented with good taste, sensitivity, and in a manner which will be considered acceptable by a mass audience. Primary human sexual characteristics will never be shown. Graphic sexual activity will never be depicted.” Perhaps most notably, the restriction on queer content was not only lifted, but language was inserted prohibiting demeaning portrayals of characters based on sexual orientation.

Ironically, perhaps the best example of an alternative to all of this comes in Grant Morrison. For all that breaking into comics after him was a curse, there is no question that Morrison benefitted from entering an industry in which Moore had already helped create spaces where he could work without as many content restrictions, and had helped erode the power of the Comics Code, which was revised in 1989, the year after Morrison’s Animal Man ran began at DC, to remove the most onerous restrictions in favor of a bland “scenes and dialogue involving adult relationships will be presented with good taste, sensitivity, and in a manner which will be considered acceptable by a mass audience. Primary human sexual characteristics will never be shown. Graphic sexual activity will never be depicted.” Perhaps most notably, the restriction on queer content was not only lifted, but language was inserted prohibiting demeaning portrayals of characters based on sexual orientation.

All of this was good for Morrison, who was always been both conscious of the sexual in comics and confident in his own depictions of them. Consider his accounts of both Superman and Batman in Supergods, which includes discussing how Joe Shuster’s design for Superman was rooted in the iconography of “extra-masculine” circus strongmen “with handlebar mustaches, pumping dumbbells in their meaty fists and staring bullishly at the camera” and how “Batman was hip to serious mind-bending drugs. Batman knew what it was like to trip balls without seriously losing his shit, and that savoir faire added another layer to his outlaw sexiness and alluring aura of decadence and wealth.” Notably, neither of these observations are particularly salacious in their accounts of sex. His comments on Batman are clearly transgressive, but this is rooted in drug use, not sexuality. In terms of sex, these are sober-minded—indeed, exceedingly so when compared to Morrison’s reputation—assessments of the sexuality that clearly plays into these heroes’ creations. And this clear-headed understanding of the sexuality of superheroes has been a regular feature of Morrison’s comic work, as in his delightfully blunt assessment of Claremont’s X-Men work, made at the tail end of his own run on the characters: “the X-Men have always been sexy and especially so since Chris Claremont injected intense doses of raw muck into the book! What do we all think the Dark Phoenix saga was about – chess?”

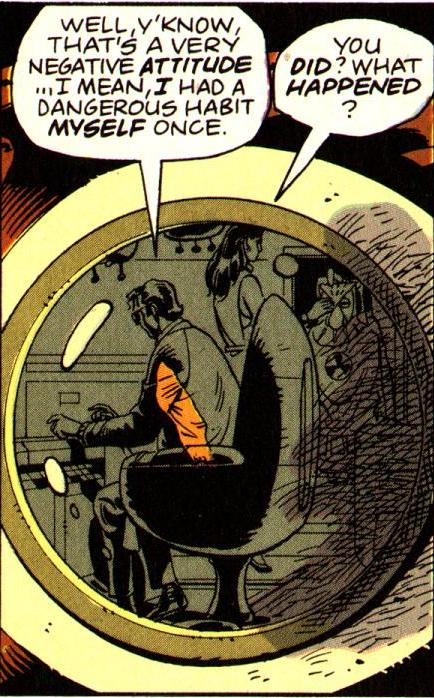

But this latter example also highlights the ways in which Morrison was comfortable deploying sexuality, including in strange and unexpected ways. No account of the sexuality of the Dark Phoenix Saga can get around the fact that Jean’s erotic awakening as Dark Phoenix comes on the back of her psychic violation by Mastermind. And this is part and parcel of the eroticism that Claremont keeps returning to across his work: a fixation on the eroticization of psychic domination and control. The same theme appears across Morrison’s work, but where Claremont is constantly snared upon it in the same way that Blake is endlessly stuck being unable to quite reconcile his conception of feminine sexuality, Morrison is cooly comfortable with the theme. Whether having a villain ask a man in suspension bondage “how must it seem to surrender the tracks and pathways of your mind to our searching fingers? To feel thought sparks retreat along neural branches down into the lightless brain root? How must it seem to be made anew?” in his early work writing The Liberators in the dying days of Warrior, writing an erotic fiction called “The Story of Zero” for Skin Two Magazine about a woman’s programming by a mysterious figure called “the Professor” (who, tellingly, is described as being in a wheelchair), in which he describes how “crawling micro-organisms spread like ink into every aroused pore, from skin to bloodstream to brain, like a fever,” to his post-War take on Wonder Woman in which he depicts the submission of a Nazi attacker on Paradise Island who, over the course of a page, talks about how her “Nazi ideals—slipping away—they—they don’t make any sense now,” then about how “I thought—I thought—I was strong. What’s wrong with me? I’m so weak—I must be weak to wish to serve weak, cruel men,” and finally ends kneeling at the feet of her new queen sobbing about how wise she is “to know this is all I ever wanted” as her queen talks about how “if you truly long to be a slave to the ideas of others, well, we can find a loving mistress to help you explore your desires in a healthier context.”

What’s striking about all of these examples is that the stories are clearly aware of their sexual facets, but are not consumed by them. Not even “The Story of Zero,” the most openly erotic of the three, is primarily about sex in the way that, say, “Night of the Chicken” is. These are scenes that have a confident control over their eroticism, as is generally the case with Morrison’s treatments of sex. None of this is to say that he’s flawless on the topic; ultimately his handling of sex is as full of tasteless errors as Moore’s, even if those errors are not so heavily clustered around poor treatments of rape and sexual assault. It’s just that Morrison is mindful of what he’s doing, writing the sexual dimensions of his comics with none of the tortured repression that characterized the decades of work before him and that so vexed Moore.

What’s striking about all of these examples is that the stories are clearly aware of their sexual facets, but are not consumed by them. Not even “The Story of Zero,” the most openly erotic of the three, is primarily about sex in the way that, say, “Night of the Chicken” is. These are scenes that have a confident control over their eroticism, as is generally the case with Morrison’s treatments of sex. None of this is to say that he’s flawless on the topic; ultimately his handling of sex is as full of tasteless errors as Moore’s, even if those errors are not so heavily clustered around poor treatments of rape and sexual assault. It’s just that Morrison is mindful of what he’s doing, writing the sexual dimensions of his comics with none of the tortured repression that characterized the decades of work before him and that so vexed Moore.

For Moore’s part, the simplest account of his problem with sex is that he recognizes the importance of the topic without ever quite being clear on what he wants to say about it. He was clear on the importance of sex and sexuality from the earliest days of his career, planning from early on to do the extended birth scene of Miracleman and pushing DC into dropping the Comics Code seal on Swamp Thing via his zombie incest plot, then taking advantage of his victory to write “Rite of Spring.” His furious reaction to the proposed DC ratings system was always rooted in an adamant rejection of censorship that was in part rooted in his disgust with the “optimistically named ‘Moral Majority’ and the rather embarrassing snakebite evangelists” who objected to depictions of sex in comics, proclaiming that “the moral pressure groups that everyone feels we should censor ourselves as protection from are dangerous and, in my terms at least, actually evil. There is only one group which would ever call for the banning of The Diary of Anne Frank, and I don’t care what they happen to be calling themselves these days.”

Moore refined this position nearly twenty years later, in his frankly astonishingly titled essay “Bog Venus vs. Nazi Cock-Ring: Some Thoughts Concerning Pornography,” published in Arthur to coincide with the release of Lost Girls. There, after tracing a capsule history of the pornographic in order to argue for its central nature to human culture, he comes out with the blunt proclamation that “sexually progressive cultures gave us mathematics, literature, philosophy, civilization, and the rest, while sexually restrictive cultures gave us the Dark Ages and the Holocaust. Not that I’m trying to load my argument, of course.”

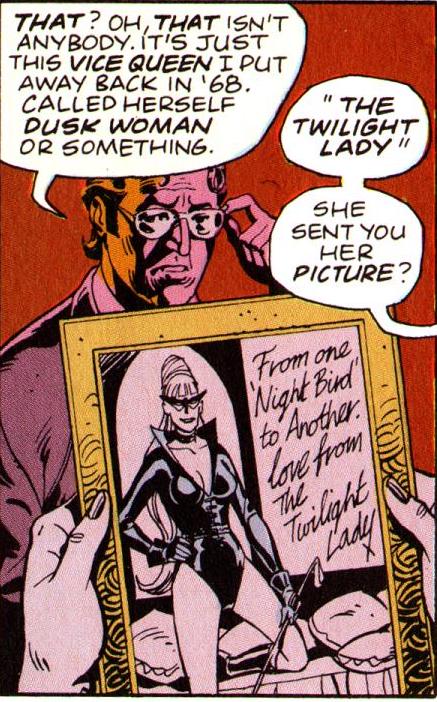

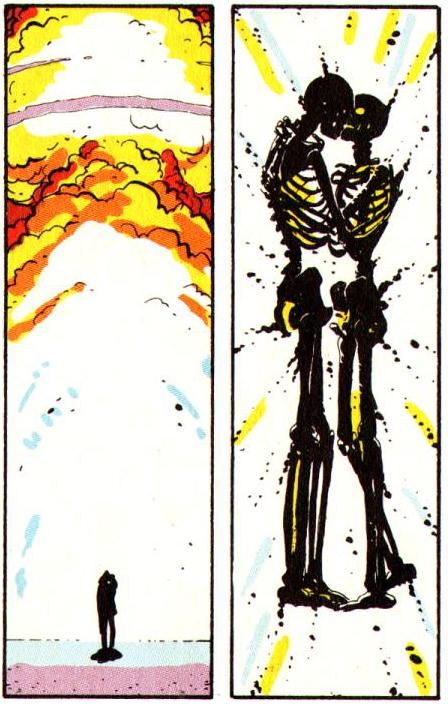

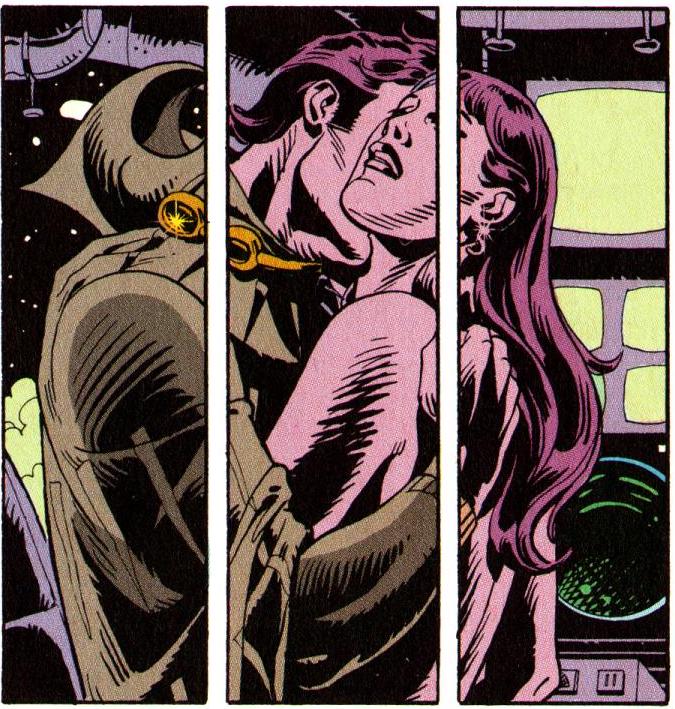

It is here that the outlines of what Moore was driving at with his invocations of sex and sexuality in Watchmen start to become clear. For Moore, the repression of sexuality is inextricably tied to brutal violence. Correspondingly, its expression offers vivid utopian possibilities. And in the context of Watchmen and its oppressive fog of nuclear paranoia, the implication is inescapable: Moore is presenting sexual liberation as a means of averting nuclear extinction. This is clearly present in Rorschach, who’s sexual repression is blatantly linked to his reactionary nihilism. But its most obvious manifestation is in the dream sequence at the heart of “A Brother to Dragons.” Following his unsuccessful attempts at sex with Laurie, Dan dreams of frantically, desperately running up to the Twilight Lady. As they embrace, their clothes disappear, and she reaches and peels open Dan’s skin, revealing the Night Owl suit beneath. He reciprocates, revealing Laurie in her Silk Spectre costume. They kiss, vaporizing to skeletons as the atomic bomb hits. The sequence is rendered in narrow half-panels along an eighteen-panel grid, giving it a frenzied claustrophobia that sets up Dan’s later claim of suffocating anxiety. But there’s equally clearly a sense of liberation in it—the realization that for Dan, Night Owl has a better claim to being his authentic self than his secret identity is the direct lead-in to him putting his costume back on and successfully getting it on. The sequence is fraught, managing to simultaneously be clangingly unsubtle and compellingly ambiguous in the way that most of Watchmen’s best moments are. But at its heart is a clear dualism between sex and the bomb.

Could it really be this simple, though? Could the whole of Alan Moore’s sexual politics really reduce so easily to a political cliche like “make love not war”? Well… yes. Alan Moore’s unreconstructed hippie streak has never been a secret. And nobody is at their most nuanced when they’re writing about the matters dearest to them. For all that Moore’s vision is resplendently intricate elsewhere, on this matter at least he is almost sweetly naive.

The problem is that this isn’t the whole of it. For all his railing against censorship, Moore has a clear personal view on what sexual expression should and shouldn’t look like. In the same essay where he blasts decrying the influence of bad depictions of sex in “plantation-slave-sex-and-bondage pieces masquerading as historical fiction.” And while he’s explicit that “it would be absurd and arrogant to write to Barbara Cartland’s publishers and demand that they stick an advisory on the covers of their books to the effect that the material within contained offensive and dangerously unrealistic portrayals of human relationships,” the moral (or at least aesthetic) judgment is clear.

Moore is even more explicit in “Bog Venus Vs. Nazi Cock-Ring,” tracing how “with each new technological advance since William Caxton it would seem pornography has both proliferated and degraded in its quality. Today’s society, thanks to the internet and other factors, is entirely saturated with erotica of the most basic, rudimentary kind; convict pornography for convict populations shuffling through life’s mess-hall without any other options than the slop they’re given. Porn is everywhere, just as it was in ancient Greece, but nowhere is it art.” Moore’s reasoning here is not rooted in moralizing so much as in the opposite, talking about a cycle whereby is use is “accompanied almost immediately by a reflex reaction of guilt, shame, embarrassment and maybe even actual self-disgust.” In contrast to this Moore suggests an alternate vision of pornography that “might welcome our sexual imagination in from the cold into the reassuring warmth of socio-political acceptability.”

The problem is straightforward: sexuality does not actually thrive in the reassuring warmth of acceptability. The sense of the forbidden and the taboo is, if not always at the very least often central to sexual pleasure. The illicit isn’t merely good for a sense of shame, but for a sense of thrill and thus pleasure. This is something Morrison always understood, and is part of why his treatments of sexuality so often work: he revels in the transgressiveness of what he presents without a sense of shame or disgust or, for that matter, a craving for the warm embrace of the Overton window. Moore, on the other hand, for all his ambitions of elevating pornography to art (or even just writing about sex in an artistic context) often ends up presenting sex in such a reverential way that even when it’s bracingly explicit as in Lost Girls it feels strangely sanitized and defanged, as though in the course of elevating it to art he’s had to chloroform it and pin it beneath glass for display.

The problem is straightforward: sexuality does not actually thrive in the reassuring warmth of acceptability. The sense of the forbidden and the taboo is, if not always at the very least often central to sexual pleasure. The illicit isn’t merely good for a sense of shame, but for a sense of thrill and thus pleasure. This is something Morrison always understood, and is part of why his treatments of sexuality so often work: he revels in the transgressiveness of what he presents without a sense of shame or disgust or, for that matter, a craving for the warm embrace of the Overton window. Moore, on the other hand, for all his ambitions of elevating pornography to art (or even just writing about sex in an artistic context) often ends up presenting sex in such a reverential way that even when it’s bracingly explicit as in Lost Girls it feels strangely sanitized and defanged, as though in the course of elevating it to art he’s had to chloroform it and pin it beneath glass for display.

It is not that Moore’s treatments of sex are all or even mostly bad. Some, indeed, are straightforwardly art; “Rite of Spring”’s vegetative erotic psychedelia remains one of the most compellingly weird and visionary portrayals of sex in comics or any other medium. Lost Girls, though undoubtedly flawed, is a compelling major work with much to say and numerous genuinely stellar moments. Even the much-maligned Neonomocion has its virtues given that it is pointedly supposed to be horror and not a source of titillation. And there are points on which he is properly admirable, most obviously in his steadfast support for queer people. But taken as a whole, it is a subject upon which Moore is uncharacteristically mediocre. When he depicts sex, he seems over-awed by it, unable to get past his own reverence.

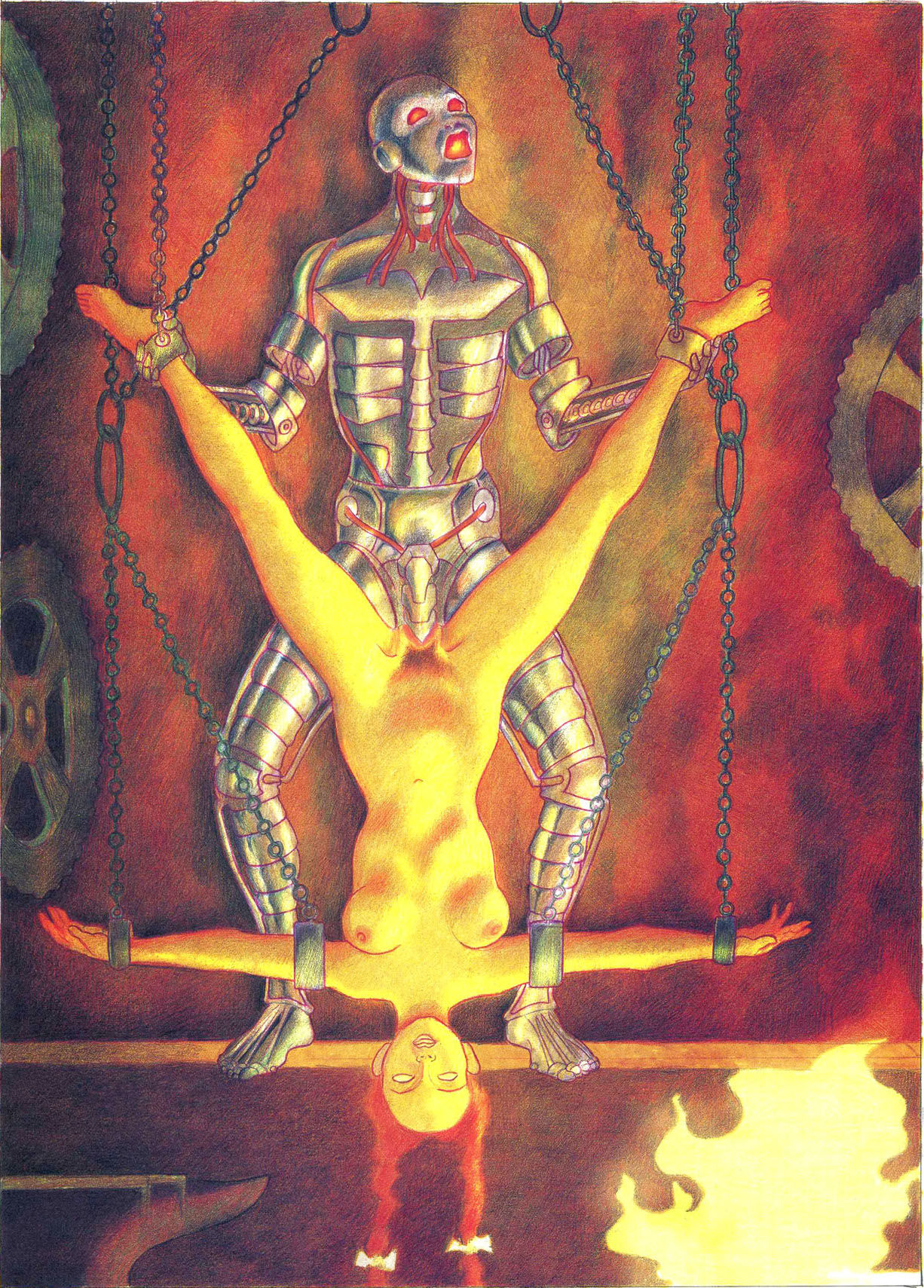

Nowhere is this clearer than his awkwardness around sexual kinks. These are in fact mostly conspicuous by their absence in his writing about sex. They appear peripherally in Neononicon, but one gets the sense he conceives of them purely as signs of Lovecraft’s sexual repression. More revealing is Lost Girls, where he does things like feature excerpts from Monsiuer Gougeur’s “scandalous white book” that consist of little more than lesbian incest pedophilia. Certainly this is certainly rife with moral horror, a point Moore remarks upon, but when he has a character describe all of this as “the dirtiest story that I’ve ever heard” and then goes into a monologue about how “pornographies are the enchanted parklands where the most secret and vulnerable of all our many selves can safely play” and how “they are our secret gardens, where seductive paths of words and imagery lead us to the wet, blinding gateways of our pleasure… beyond which, things may only be expressed in language that is beyond literature…beyond all words” it is difficult not to feel a bit underwhelmed. It’s certainly not that Lost Girls is devoid of kink, but what’s there tends to come more from Melinda Gebbie’s contributions, particularly the luscious splash pages in which she renders the girls’ sexual adventures in the iconography of their fictional origins, such as the genuinely striking image just two chapters later of an android Tin Man fucking a white-eyed Dorothy in inverted suspension bondage, a page that thrums with a sexual charge that nothing Moore has ever constructed even approaches precisely because it is willing to embrace its illicitness without any effort, in the moment, to argue for its larger aesthetic worth.

In fact, the most substantial engagement with the idea of sexual kink in Moore’s entire oeuvre comes in “A Brother to Dragons” itself, where he finds himself forced for thematic reasons to grapple with the phenomenon of people finding sexual gratification in dressing in leather and beating other people up. That the result is the least satisfying of Watchmen captures the tensions in play here in a perfect microcosm, although it must be noted that bringing up the rear in Watchmen is still operating in a different league from most other comics. And if it is an aesthetic failure, at least it’s an honest one, achieved by Moore flinging himself at the limits of his vision and making the best stand he can.

In fact, the most substantial engagement with the idea of sexual kink in Moore’s entire oeuvre comes in “A Brother to Dragons” itself, where he finds himself forced for thematic reasons to grapple with the phenomenon of people finding sexual gratification in dressing in leather and beating other people up. That the result is the least satisfying of Watchmen captures the tensions in play here in a perfect microcosm, although it must be noted that bringing up the rear in Watchmen is still operating in a different league from most other comics. And if it is an aesthetic failure, at least it’s an honest one, achieved by Moore flinging himself at the limits of his vision and making the best stand he can.

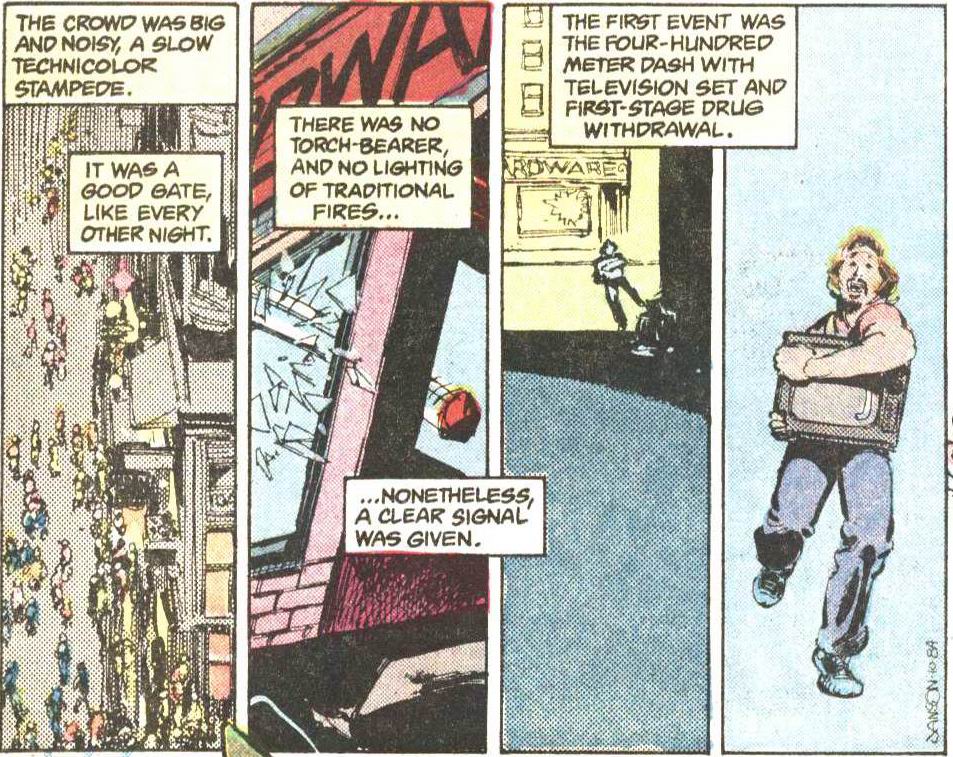

From the start, “A Brother of Dragons” finds itself in a tangled thicket of repressed desire. Dan shows off his collection of expensive toys to Laurie, who “really impressed by all this equipment” despite Dan’s observation of “all these leaks and puddles” on the floor. They look at the photo of the leather-clad Twilight Lady and at Dan’s various outfits, talking about how Dan was able to give up his dangerous habit. Their dialogue is full of lines that are at once compelling and flagrantly inserting subtext as text, such as Laurie describing Dan’s prototype exoskeleton that broke his arm as “the sort of costume that could really mess you up,” to which Dan sardonically replies, “is there any other sort?” And subsequently, after their successful post-tenement fire coupling, Laurie asks, “did the costumes make it good,” to which Dan earnestly replies “Yeah, I guess the costumes had something to do with it. It just feels strange, you know? To come out and admit that to somebody. To come out of the closet,” a stretch of dialogue that takes place in a panel featuring the issue’s last close-up of the Night Owl goggles. And the overall parallels with BDSM are clear, especially in the “dangerous habit” line which is, as “The Judge of All the Earth” suggests, fundamentally focused not merely on dressing up in costumes but on beating the shit out of people.

It’s important to note that not all of this is running in the same direction. Most obviously, although violence is a part of BDSM, consensual sadism and things like the brutal fight scene of Watchmen #3 have virtually nothing to do with one another. Past that, Moore is simultaneously trying to have the costume work as a metonym for secret identities/the closet and as a fetish object in its own right in a way that doesn’t come close to resolving. His heart is also clearly not in the underlying equivocating of sex and violence, which requires him to take violence seriously as a substitute for sex as opposed to the primary failure mode of sexual repression. And because the overall plot of the issue is reparative, with the focus on Dan overcoming his impotence by accepting his identity as a superhero, Moore ultimately can’t entirely reject the validity of violence as a sexual outlet within “A Brother of Dragons.” His best effort to this effect—to have the bit of superheroics engaged in by Dan and Laurie be rescuing people from a tenement fire—works in the immediate term, but even this is sharply undermined by the fact that the endpoint of their subsequent coupling is a decision to spring Rorschach from prison.

Ah yes, Rorschach. If “The Abyss Gazes Also” and “A Brother of Dragons” are taken as a structural equivalent to the Ozymandias panel at the heart of “Fearful Symmetry,” then Rorschach is clearly at the heart of this pairing. Despite his absence from “A Brother of Dragons,” he haunts the entire issue: Dan recalls his “mask-killer” hypothesis at the beginning when he hears Laurie’s cries from the basement, they watch a news story about him shortly before their failed coupling, and Dan’s decision to free him from prison (and Laurie’s incredulity) are the note upon which it ends. The issues also share a variety of thematic concerns, albeit in a cracked mirror way: consider “A Brother of Dragons”’s repeated motif of panels focused on Dan’s goggles as compared with “The Abyss Gazes Also”’s obsession with the act of looking. Similarly, the Freudian obsessions of “The Abyss Gazes Also,” though unvoiced within “A Brother of Dragons,” are clearly underpinning the issue’s forensic examination of sexuality, anxiety, and repression.

Moore admits as much, noting that “It’s difficult pinning down what’s symmetrical to what—I mean to me, at least to some extent, there’s an equally good case for contrasting Nite Owl and Rorschach… Episode 6 was about the most depressing of the whole series; Episode 7 was probably the most uplifting. So there is a symmetry in the series.” And he’s right that the comparison makes sense. Rorschach and Night Owl provide two starkly different visions of the same basic question. Night Owl ultimately sorts through his sexual confusion and attains a level of functionality that allows him to balance the thrill of his superhero identity with the grounded materialism of his human one, whereas Rorschach dives ever deeper into being a superhero, explicitly proclaiming the death of Walter Kovacs in favor of the dark purity of Rorschach. Both men are compelled to put on a costume and engage in violent retribution of dubious practical utility, but Night Owl is able to contextualize this desire in a larger sense of personhood, whereas Rorschach is ultimately consumed utterly by his obsessions.

Moore admits as much, noting that “It’s difficult pinning down what’s symmetrical to what—I mean to me, at least to some extent, there’s an equally good case for contrasting Nite Owl and Rorschach… Episode 6 was about the most depressing of the whole series; Episode 7 was probably the most uplifting. So there is a symmetry in the series.” And he’s right that the comparison makes sense. Rorschach and Night Owl provide two starkly different visions of the same basic question. Night Owl ultimately sorts through his sexual confusion and attains a level of functionality that allows him to balance the thrill of his superhero identity with the grounded materialism of his human one, whereas Rorschach dives ever deeper into being a superhero, explicitly proclaiming the death of Walter Kovacs in favor of the dark purity of Rorschach. Both men are compelled to put on a costume and engage in violent retribution of dubious practical utility, but Night Owl is able to contextualize this desire in a larger sense of personhood, whereas Rorschach is ultimately consumed utterly by his obsessions.

It goes without saying at this point that the essential difference is sex. What Night Owl is able to do that Rorschach isn’t is to recognize the sexual component of his compulsion, whereas Rorschach is hemmed in by the abuse and trauma of his childhood and fundamentally unable to see that his desire to bring righteous vengeance upon criminals is sexual in its nature. It is the old familiar point at the heart of Moore’s writing on sex: that sexual repression is a destructive path to violence while open sexual expression allows mystical and political liberation.

It goes without saying at this point that the essential difference is sex. What Night Owl is able to do that Rorschach isn’t is to recognize the sexual component of his compulsion, whereas Rorschach is hemmed in by the abuse and trauma of his childhood and fundamentally unable to see that his desire to bring righteous vengeance upon criminals is sexual in its nature. It is the old familiar point at the heart of Moore’s writing on sex: that sexual repression is a destructive path to violence while open sexual expression allows mystical and political liberation.

Again, there is something unpleasant to this given that Rorschach’s repulsion at sexuality is clearly inspired by Steve Ditko’s apparent asexuality. And the problems deepen if one looks at Watchmen’s larger sense of reparative sexuality, especially the plot point of Sally Jupiter’s forgiving of Eddie Blake’s raping her and the eventual consensual affair with him that produced Laurie, a character beat that is on the one hand a commendably nuanced treatment of the complex psychologies of rape victims and on the other, taken in the context of the book’s larger sentiments on accepting sexual desires, something that comes disastrously close to implying a sort of moral or personal obligation on the part of rape victims to forgive their assailants. And the larger scale prevalence of rape in Moore’s ouvre does him no favors on this point.

But for all its flaws, there remains something noble and sympathetic at the core of Moore’s position. It’s not, after all, as though he’s wrong about the terrible consequences of sexual repression. It’s not even as though he’s wrong about the connections between sexual freedom and violence rates, although the research is not quite the towering monument of clarity he likes to suggest. And the naïveté of straight-facedly proclaiming sex to be a viable solution to the Cold War threat of nuclear annihilation cuts both ways, being just as admirable in its complete refusal to bow to the demands of reality as it is frustrating. Yes, this exposes one of the limits of Moore’s thought, but every artist’s vision has limits. And like any limit, it represents a failure of that vision. But this is hardly the worst way to fail; better this than stumbling over the basic validity of female sexuality and subjectivity, as Blake did, or being a drug-addicted asshole to everybody like Crowley.

Where Moore’s deliberate balancing act does shift from the simple inadequacies inherent in working at one’s artistic limits into something he outright doesn’t quite seem able to control, however, is in his attempted contrasting of Night Owl and Rorschach. Moore is clear that he wants Night Owl to come out the better in this. It’s implicit in his declaration that “A Brother of Dragons” is uplifting in contrast to the nihilism of Rorschach’s issue. And it’s implicit when he says that in a real sense Dan and Laurie are the heroes of the book ”because they are the only human characters in it.” But while it’s clear that the symmetry at the heart of the book is supposed to reveal Night Owl as the preferable figure, this simply doesn’t work. “A Brother of Dragons” is an awkward, preachy chapter, while “The Abyss Gazes Also” is an electrifying highlight of the entire series. And so for all that Moore presents Night Owl as preferable to Rorschach, ultimately Rorschach cannot be so easily suppressed.

Where Moore’s deliberate balancing act does shift from the simple inadequacies inherent in working at one’s artistic limits into something he outright doesn’t quite seem able to control, however, is in his attempted contrasting of Night Owl and Rorschach. Moore is clear that he wants Night Owl to come out the better in this. It’s implicit in his declaration that “A Brother of Dragons” is uplifting in contrast to the nihilism of Rorschach’s issue. And it’s implicit when he says that in a real sense Dan and Laurie are the heroes of the book ”because they are the only human characters in it.” But while it’s clear that the symmetry at the heart of the book is supposed to reveal Night Owl as the preferable figure, this simply doesn’t work. “A Brother of Dragons” is an awkward, preachy chapter, while “The Abyss Gazes Also” is an electrifying highlight of the entire series. And so for all that Moore presents Night Owl as preferable to Rorschach, ultimately Rorschach cannot be so easily suppressed.

Indeed, as noted, by the end of the issue he’s already resurgent, forcing his way back into the narrative. Against all odds and everything Moore is trying to do, the endpoint of Night Owl’s sexual liberation is not freedom from nuclear apocalypse; it’s Rorschach. But this is Rorschach’s nature; he is impossible to contain or keep under control. And ultimately it would not just be Moore’s utopian vision of sex that would find itself unable to escape his influence, but the entire superhero genre.

Indeed, as noted, by the end of the issue he’s already resurgent, forcing his way back into the narrative. Against all odds and everything Moore is trying to do, the endpoint of Night Owl’s sexual liberation is not freedom from nuclear apocalypse; it’s Rorschach. But this is Rorschach’s nature; he is impossible to contain or keep under control. And ultimately it would not just be Moore’s utopian vision of sex that would find itself unable to escape his influence, but the entire superhero genre.

“Oh, ugh. Is love really going to save us all?”

“Of course it is. Anyone who thinks otherwise gets stomped into paste.” —Kieron Gillen, Young Avengers

{Several pieces of Moore’s brief DC Comics career remain to be discussed. The most obvious of these in terms of Watchmen is “For the Man Who Has Everything,” done with Dave Gibbons in in Superman Annual #11 in 1985. Gibbons had made the jump to DC slightly before Moore, having been tapped by Len Wein in 1982 to work on a series of Green Lantern backups and, eventually, on the main book. Gibbons was in many regards a natural fit for American superhero comics, and especially for DC, where he quickly established himself as a major talent. His simple, clean style made for immaculately clear storytelling, and his characters had an earnest straight-forwardness that evoked the classic silver age work of Curt Swan and Dick Sprang. Nevertheless, he was an inventive and flexible artist who, as Moore had noted during their time doing Future Shocks for 2000 AD, “was prepared to draw whatever absurd amount of detail you should ask for, however ludicrous and impractical.”

{Several pieces of Moore’s brief DC Comics career remain to be discussed. The most obvious of these in terms of Watchmen is “For the Man Who Has Everything,” done with Dave Gibbons in in Superman Annual #11 in 1985. Gibbons had made the jump to DC slightly before Moore, having been tapped by Len Wein in 1982 to work on a series of Green Lantern backups and, eventually, on the main book. Gibbons was in many regards a natural fit for American superhero comics, and especially for DC, where he quickly established himself as a major talent. His simple, clean style made for immaculately clear storytelling, and his characters had an earnest straight-forwardness that evoked the classic silver age work of Curt Swan and Dick Sprang. Nevertheless, he was an inventive and flexible artist who, as Moore had noted during their time doing Future Shocks for 2000 AD, “was prepared to draw whatever absurd amount of detail you should ask for, however ludicrous and impractical.”

Although Gibbons and Moore had never embarked on an extended collaboration, they had a strong collaboration on these short pieces, and once Moore also made the jump to the US market the idea that they would eventually work together seemed self-evident to everyone involved. The only difficulty proved finding a suitable venue. At one point, Gibbons was invited to join Swamp Thing, which he declined feeling (not unreasonably) that he was a bad fit for the character, although this appears to have pre-dated Moore’s involvement on the book. Moore wrote pitches for a 1950s-set Martian Manhunter series about McCarthyite paranoia and a Challengers of the Unknown series that would focus on the politically destabilizing effects of Superman’s emergence, along with less serious ideas like a Tommy Tomorrow reboot that was motivated primarily by Moore and Gibbons’s delight in the fact that the lead character wore shorts. None of these, however, entered production. But when Gibbons was asked by Julius Schwartz to do a Superman story for him (in Gibbons’s telling the same night he secured the Watchmen gig from Dick Giordano), he suggested Moore as a writer. The result was “For the Man Who Has Everything.”

From the internal perspective of Moore’s career, “For the Man Who Has Everything” is unremarkable. Batman, Robin, and Wonder Woman go to visit Superman at the Fortress of Solitude for his birthday, where they discover him ensnared in an alien plant that is quickly revealed to be a plot by the intergalactic conquerer Mongul to kill Superman by trapping him in a fantasy world offering his heart’s desire. Everyone struggles, and eventually Mongul is defeated by his own trap. The bulk of this is straightforward superhero action. Mongul pummels Wonder Woman for a bit as Batman and Robin try to get the plant off Superman; this works, but the plant ends up on Batman, so Superman goes and pummels Mongul for a bit while Robin gets it off of Batman to drop it on Mongul. The interesting part is Superman’s time in the fantasy world.

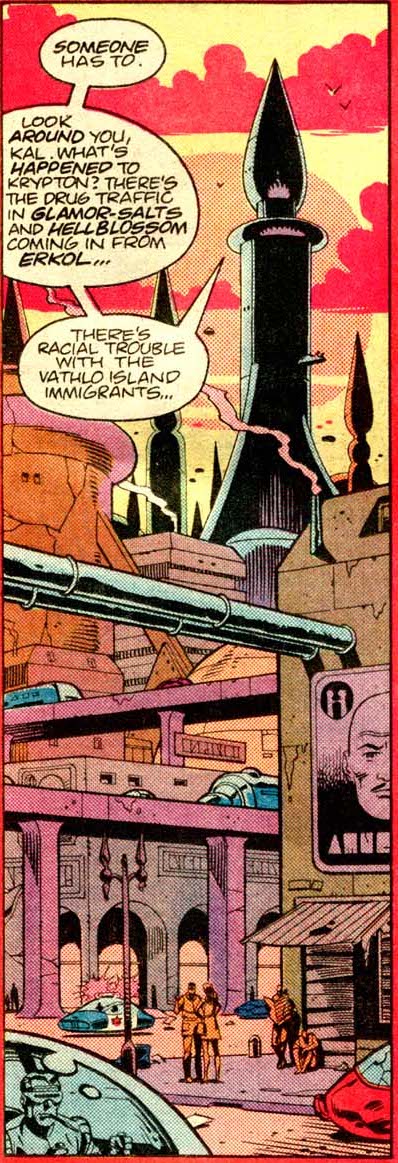

This is, broadly, a recurrent trope for Moore; he used something like it early in Swamp Thing as the title character contemplates the temptations of oblivion after finding out that he’s not Alec Holland, and a more starkly depressing version of it appears in the 2000 AD short “The Time Machine.” And, of course, the idea of alternate worlds that exist as mental states would only increase in importance after Moore became a practicing magician. In the case of “For the Man Who Has Everything,” the trope takes the form of an alternate timeline in which Krypton was not destroyed. What proves compelling about this is the degree to which Superman’s imagined Krypton is very far from utopian. Moore conjures a world in which Krypton is grappling with a fascist movement called the Sword of Rao, which counts Superman’s father Jor-El, bitter from his political ostracism after wrongly predicting the destruction of Krypton, as one of its most prominent supporters. Superman’s cousin. Kara, who in the DC universe is Supergirl, is severely beaten by a second radical sect that objects to the use of the Phantom Zone to punish criminals and blames the house of El for its invention. It’s a troubling, unsettling world, rendered of course exquisitely by Dave Gibbons who, along with colorist Tom Ziuko, craft a compelling futuristic utopia that nevertheless drips with a noir sense of forboding. The problem is that this world is disposed of about halfway through the comic, with nothing really left but punching in the back half. It’s good punching, with an effective resolution and some good caption boxes describing the Fortress of Solitude as Superman and Mongul rampage through it, but above average superhero comics are not something that stands out in the context of Moore’s larger ouvre.

Indeed, Moore would go on to use a startlingly similar idea in another Superman story released just two weeks earlier in DC Comics Presents #85. This was an anthology book with no consistent team that presented a new Superman team-up every month, and Moore was tapped to do a Superman/Swamp Thing story. In it he has Superman infected with an alien fungus, the bloodmorel, which causes the victim to become feverish, hallucinate, and eventually die from a frenzied overexertion and, for mildly strained reasons (he wants to die alone and it’s “the one place in America with no indigenous superhumans”) he decides to rent a car and drive south in order to do so. Eventually he crashes his car and begins to hallucinate wildly in a sequence that owes no small debt to Saga of the Swamp Thing #22 until he is found by Swamp Thing and ultimately saved. It is ruthlessly pedestrian, but its existence reveals the extent to which, for all his grandeur and monstrosity, Moore was still a jobbing writer with a box of standard tricks.

But for all that its status within Moore’s career is wholly unremarkable, within the context of DC Comics “For the Man Who Has Everything” becomes altogether more extraordinary. It is routinely listed as one of the best Superman stories of all time, and has been adapted both in animated form for the 00s-era Justice League Unlimited cartoon and in live action television, where it was rewritten as a Supergirl stort in 2016. And it’s easy to see how a mid-tier Alan Moore story came to stand out so much in comparison to other Superman tales of the era. The year before “For the Man Who Has Everything,” the Superman Annual featured a barely coherent Elliot Maggin story about a sword as old as the universe that (for some reason) also carries the name Superman; the year after, Cary Bates and Alex Savihk offered a thoroughly unremarkable Lex Luthor story. Both feel bizarrely dated, as though they don’t even belong in the same decade as “For the Man Who Has Everything.” In a pond of such desperately middling talent, Moore was not so much a big fish as a leviathan, and even his minor works loomed large.