Chapter Eight: This is the Future (Old Ghosts)

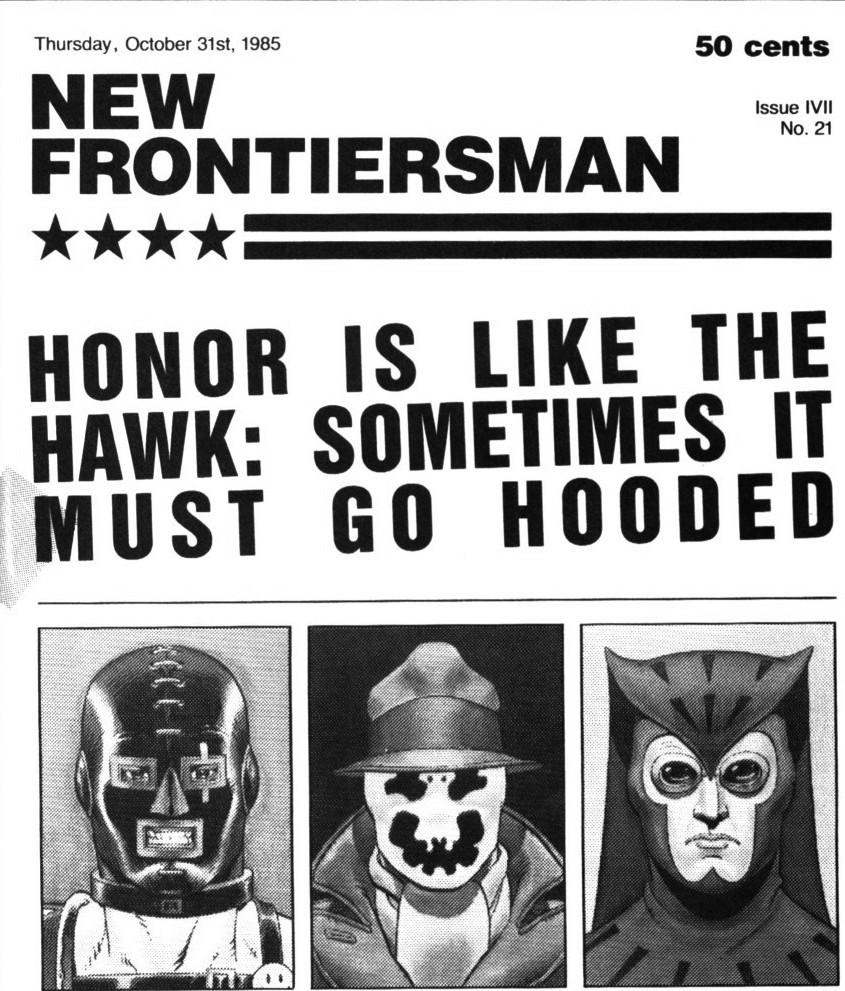

The core of the problem was that from DC’s perspective, the lesson of Watchmen could only ever be one thing: things like this sold. And within the post-Crisis reality of the direct market, what DC specifically cared about was what fans said. The simple reality is that what the vocal fans who showed up and bought Watchmen in their specialist comic book stores liked most about the book wasn’t the moving explorations of sexuality in “A Brother To Dragons”; it was Rorschach being a moody badass in “The Abyss Gazes Also.” And so this is what DC imitated.

The core of the problem was that from DC’s perspective, the lesson of Watchmen could only ever be one thing: things like this sold. And within the post-Crisis reality of the direct market, what DC specifically cared about was what fans said. The simple reality is that what the vocal fans who showed up and bought Watchmen in their specialist comic book stores liked most about the book wasn’t the moving explorations of sexuality in “A Brother To Dragons”; it was Rorschach being a moody badass in “The Abyss Gazes Also.” And so this is what DC imitated.

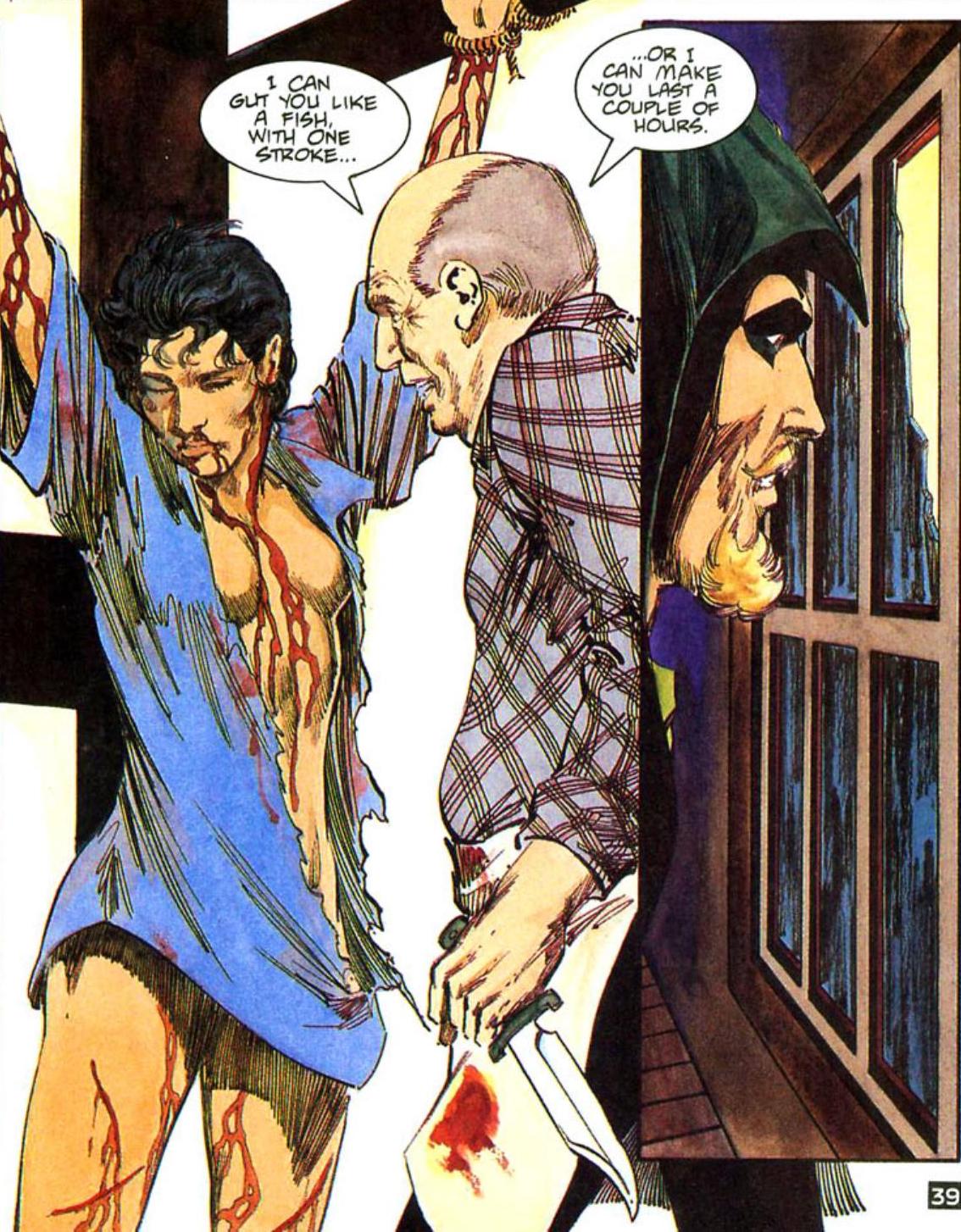

This, of course, was not unique to Watchmen—the kind of hard-edged and violent antihero represented by Rorschach was, to DC’s mind, part and parcel of a trend of dark and violent superhero comics that also included Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns and Mike Grell’s Green Arrow: The Longbow Hunters. This, in other words, was something they already knew how to imitate, and that Moore was always one of several writers capable of providing. Indeed, in most regards Moore was always an imitator in this regard, putting his own spin on a foundation that had been laid down by Miller.

It’s easy, looking at individual comics and the aesthetic visions they contain, to fall into a sense of thinking of comics as a matter of single vision, where Watchmen, The Dark Knight Returns, and The Longbow Hunters represent an argument that noir-inflected violence for teenage boys is what comics should be in some absolute and total sense. Phrased this way, the fallacy is obvious, but even recognizing that, it’s easy to forget just how many different aesthetics coexist under the overall brand represented by the DC bullet logo.

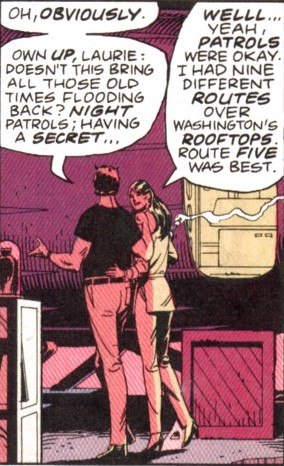

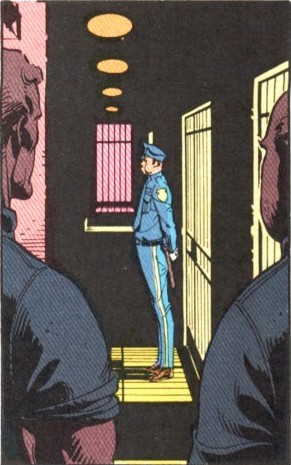

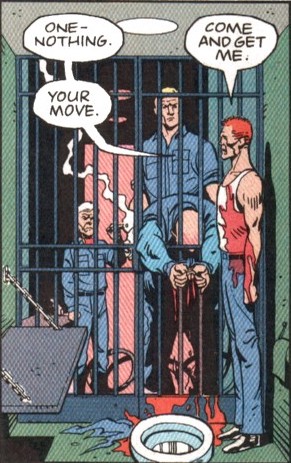

Consider January of 1987, the month that Moore finally came to the decision that he would not accept any new work from DC. In addition to Watchmen #8, in which Rorschach breaks out of prison with the help of Dan and Laurie after violently murdering his way through a number of inmates, high profile comics being released included the final issue of Legends, DC’s first attempt to duplicate the success of Crisis on Infinite Earths, two issues of John Byrne’s Superman run, and an issue of George Pérez’s Wonder Woman. In more grim and gritty terms, DC released an issue of Vigilante, with its right-wing fantasy of extrajudicial executions, and The Question, which saw Denny O’Neil putting his own spin on Rorschach’s source material, and the third installment of Frank Miller’s post-Crisis Batman: Year One relaunch. But even within the Batman line, that same month saw the release of Detective Comics #573, a goofball issue featuring the Mad Hatter, albeit one that ends with Robin being shot and gravely wounded. But DC still had at least one eye firmly situated on the past. Other titles included Infinity Inc., co-written by Roy Thomas, a twenty-year veteran of the industry who had succeeded Stan Lee as editor in chief at Marvel Comics. Sgt. Rock featured a story written by Robert Kanigher, who had forty years earlier taken over Wonder Woman following the death of William Moulton Marston. Elsewhere, industry veterans like Michael Fleisher, Len Wein, and Curt Swan were still getting work, albeit mostly on minor titles featuring licensed properties. No single and coherent sense of what comics were or how they should be prevailed—instead DC put out a variety of titles that catered to various factions within their audience.

Consider January of 1987, the month that Moore finally came to the decision that he would not accept any new work from DC. In addition to Watchmen #8, in which Rorschach breaks out of prison with the help of Dan and Laurie after violently murdering his way through a number of inmates, high profile comics being released included the final issue of Legends, DC’s first attempt to duplicate the success of Crisis on Infinite Earths, two issues of John Byrne’s Superman run, and an issue of George Pérez’s Wonder Woman. In more grim and gritty terms, DC released an issue of Vigilante, with its right-wing fantasy of extrajudicial executions, and The Question, which saw Denny O’Neil putting his own spin on Rorschach’s source material, and the third installment of Frank Miller’s post-Crisis Batman: Year One relaunch. But even within the Batman line, that same month saw the release of Detective Comics #573, a goofball issue featuring the Mad Hatter, albeit one that ends with Robin being shot and gravely wounded. But DC still had at least one eye firmly situated on the past. Other titles included Infinity Inc., co-written by Roy Thomas, a twenty-year veteran of the industry who had succeeded Stan Lee as editor in chief at Marvel Comics. Sgt. Rock featured a story written by Robert Kanigher, who had forty years earlier taken over Wonder Woman following the death of William Moulton Marston. Elsewhere, industry veterans like Michael Fleisher, Len Wein, and Curt Swan were still getting work, albeit mostly on minor titles featuring licensed properties. No single and coherent sense of what comics were or how they should be prevailed—instead DC put out a variety of titles that catered to various factions within their audience.

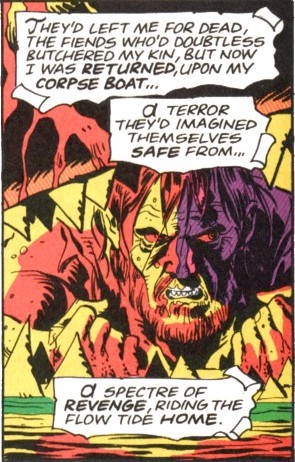

But in this regard Moore’s departure really did pose a problem for DC, not because they couldn’t stamp out an endless parade of violent sociopath protagonists a la Rorschach but because of the other massive success Moore had penned for them: Swamp Thing. This book, with its philosophical ambitions, grandoisely poetic narration, and sense of macabre horror was, after all, the series that established Alan Moore as a major figure in the US market. And unlike Rorschach (and more in common with the rest of Watchmen), Swamp Thing did not fit easily into a trend with other practitioners. It was still entirely singular—a comic the likes of which the American market had simply never seen before. How was DC to copy it?

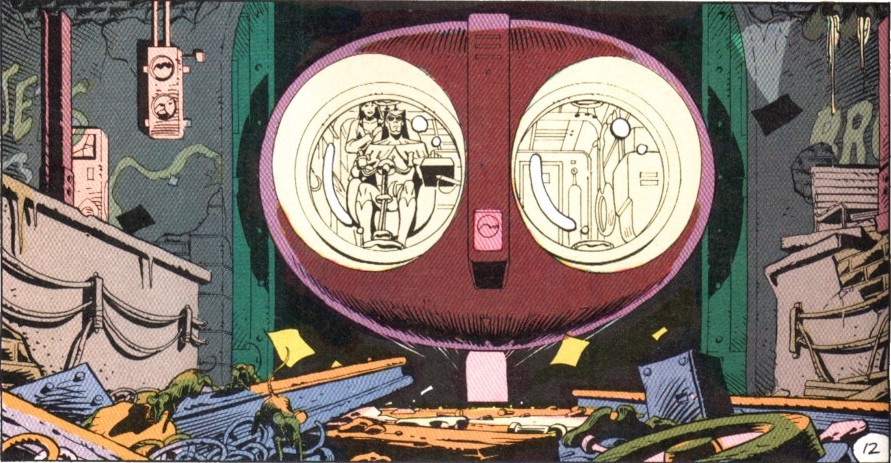

On Swamp Thing itself, at least, the answer was easy enough. DC had been working on the matter of succession over the course of Moore’s final arc playing with the far-flung sci-fi aspects of the company’s history, dropping a pair of one-offs into Moore’s arc in which two of the most obvious candidates could audition for the writer job. The first, Swamp Thing #59, was one of DC’s other January 1987 books, and featured Steve Bissette penning an old school horror issue employing Anton Arcane again. The second came three issues later in Swamp Thing #62, and saw the other primary artist of Moore’s Swamp Thing run, Rick Veitch, take over to have Swamp Thing encounter Jack Kirby’s New Gods in a heavily Jim Starlin-inspired issue that served as the last of Swamp Thing’s outer space adventures before his return to Earth the next month.

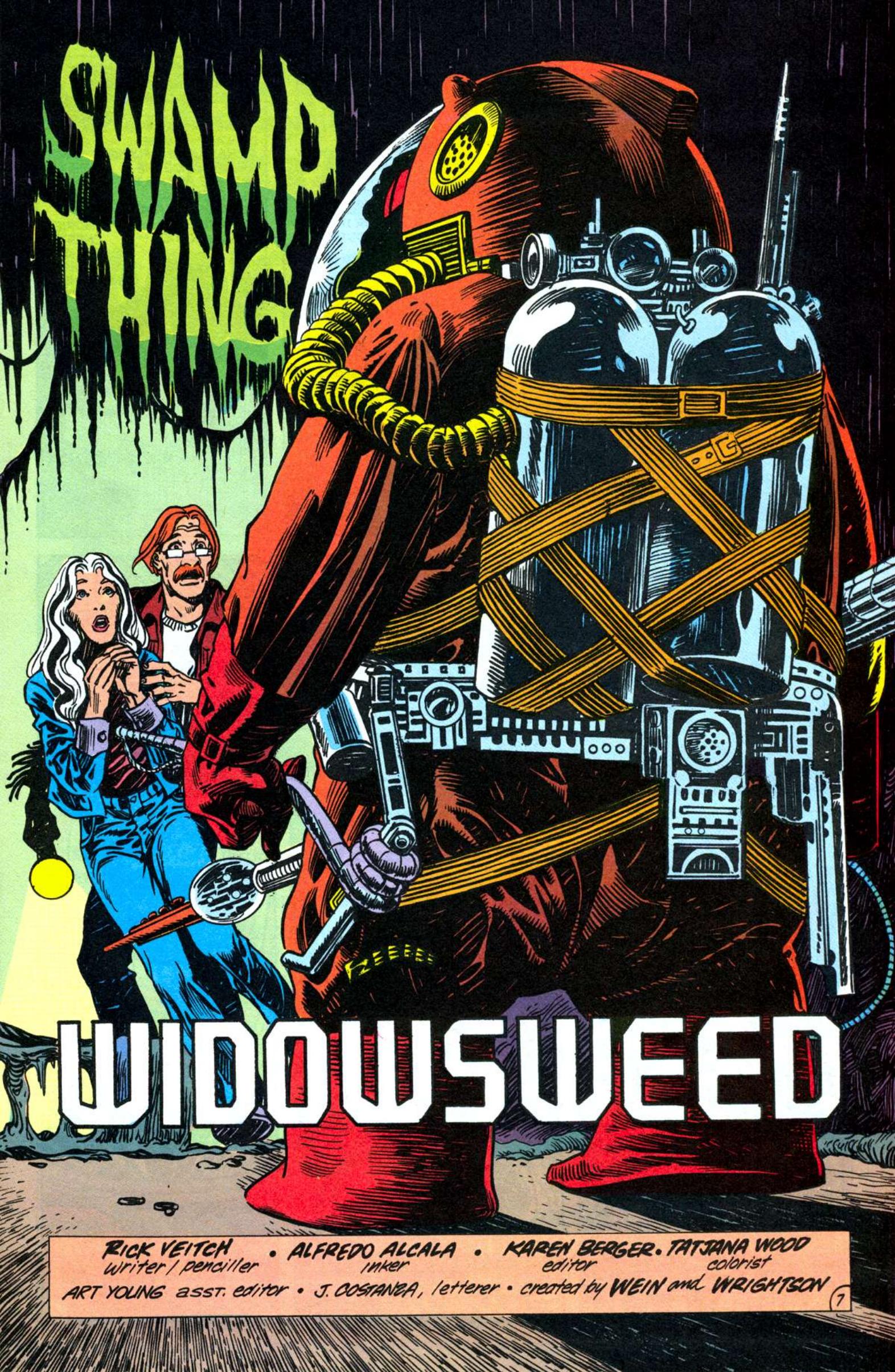

Ultimately DC decided to go with the latter option, and Rick Veitch took over the book starting with Swamp Thing #65 a few weeks after the final issue of Watchmen hit. In marked and understandable contrast to Moore, who arrived on the title by constructing a triumphant bonfire for everything Marty Pasko had done on the title in favor of a radical reinvention of the central premise, Veitch’s first issue is almost entirely focused on establishing continuity with what came before. The issue features Swamp Thing communing with the Parliament of Trees, Abby on a psychedelic trip calling back to “Rite of Spring” in which she encounters visions of Anton Arcane, her comatose husband, and even the fear demon from the first year of Moore’s run, and culminates with the reappearance of John Constantine. It is a comprehensive statement of how little anything is going to change, emphasized by the fact that Veitch was still pencilling the book along with writing it, backed by the same inker in Alfredo Alcala, the same colorist in Tatjana Wood, and the same letterer in John Costanza. And the press around the comic was unsurprisingly keen to stress the seamlessness of the transition, with Veitch talking in interviews about how he “slid into the ‘Swamp Thing style of writing’” and tried to maintain Moore’s style of visual transitions.

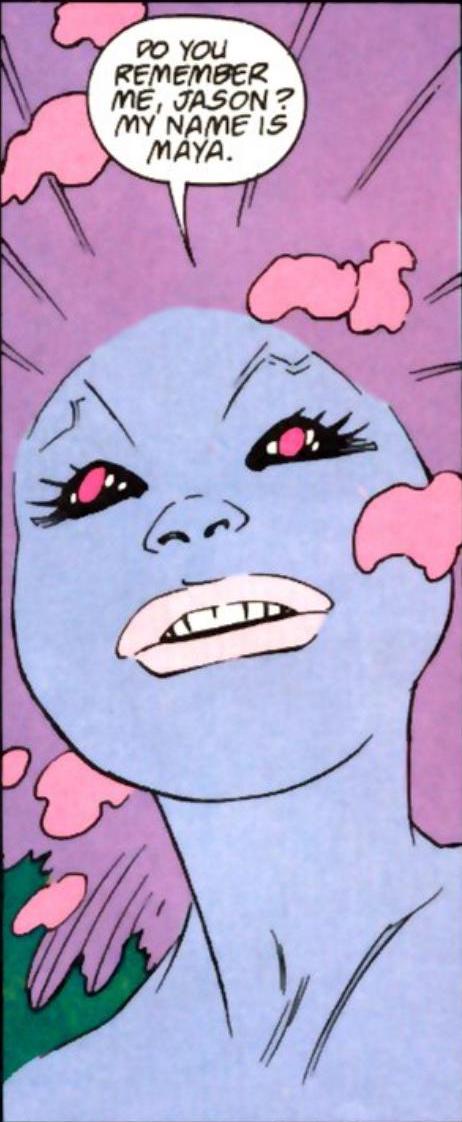

This approach largely characterizes the first couple of Veitch’s issues, sprinkled with some high-profile guest spots. Swamp Thing #66 brings back Jason Woodrue and features another psychedelia sequence for Abby, this time with a trip into hell to check in on all the people from the Sunderland Corporation that Swamp Thing killed off late in the Moore run, but also throws in a guest appearance by Batman. Issue #67, meanwhile, brings back Alan Moore’s stand-in Gene LaBostrie from “Return of the Good Gumbo” while contriving to have Swamp Thing fight midlist Batman villain Solomon Grundy and, in the final pages, at least temporarily writing John Constantine out of the story.

This approach largely characterizes the first couple of Veitch’s issues, sprinkled with some high-profile guest spots. Swamp Thing #66 brings back Jason Woodrue and features another psychedelia sequence for Abby, this time with a trip into hell to check in on all the people from the Sunderland Corporation that Swamp Thing killed off late in the Moore run, but also throws in a guest appearance by Batman. Issue #67, meanwhile, brings back Alan Moore’s stand-in Gene LaBostrie from “Return of the Good Gumbo” while contriving to have Swamp Thing fight midlist Batman villain Solomon Grundy and, in the final pages, at least temporarily writing John Constantine out of the story.

This is not to say that Veitch did not introduce his own plot elements. Swamp Thing #65 features the reveal that the Parliament of Trees believed that Swamp Thing really was dead when his consciousness fled offworld, and that they thus commenced the creation of a new elemental to take his place. They assert that the only way to restore balance is now for Swamp Thing to kill the vestigial spirit of his successor, which he refuses to do. Nor is it the case that the early months of Veitch’s run are all so focused on nostalgia for the halcyon days of three months prior. Two weeks after Veitch’s first issue DC released Swamp Thing Annual #3. Working from an underlying story hook toyed with by Moore but never developed before he decided to move on from the book, Veitch penned a ridiculously silly story in which Swamp Thing’s life intersects with the famously and bewilderingly large stable of DC gorilla characters. Featuring appearances by Angel and the Ape, Gorilla Grodd, B’wana Beast and Djuba, Congo Bill, George Dyke (the Gorilla Boss of Gotham City), Solovar, and Monsieur Mallah, the story is a madcap romp that is profoundly stupid in all of the best ways, and made it clear that Veitch had arrows in his quiver besides meekly imitating his predecessor. Nevertheless, the basic approach was clear: if you liked Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing, you’ll probably still like this one.

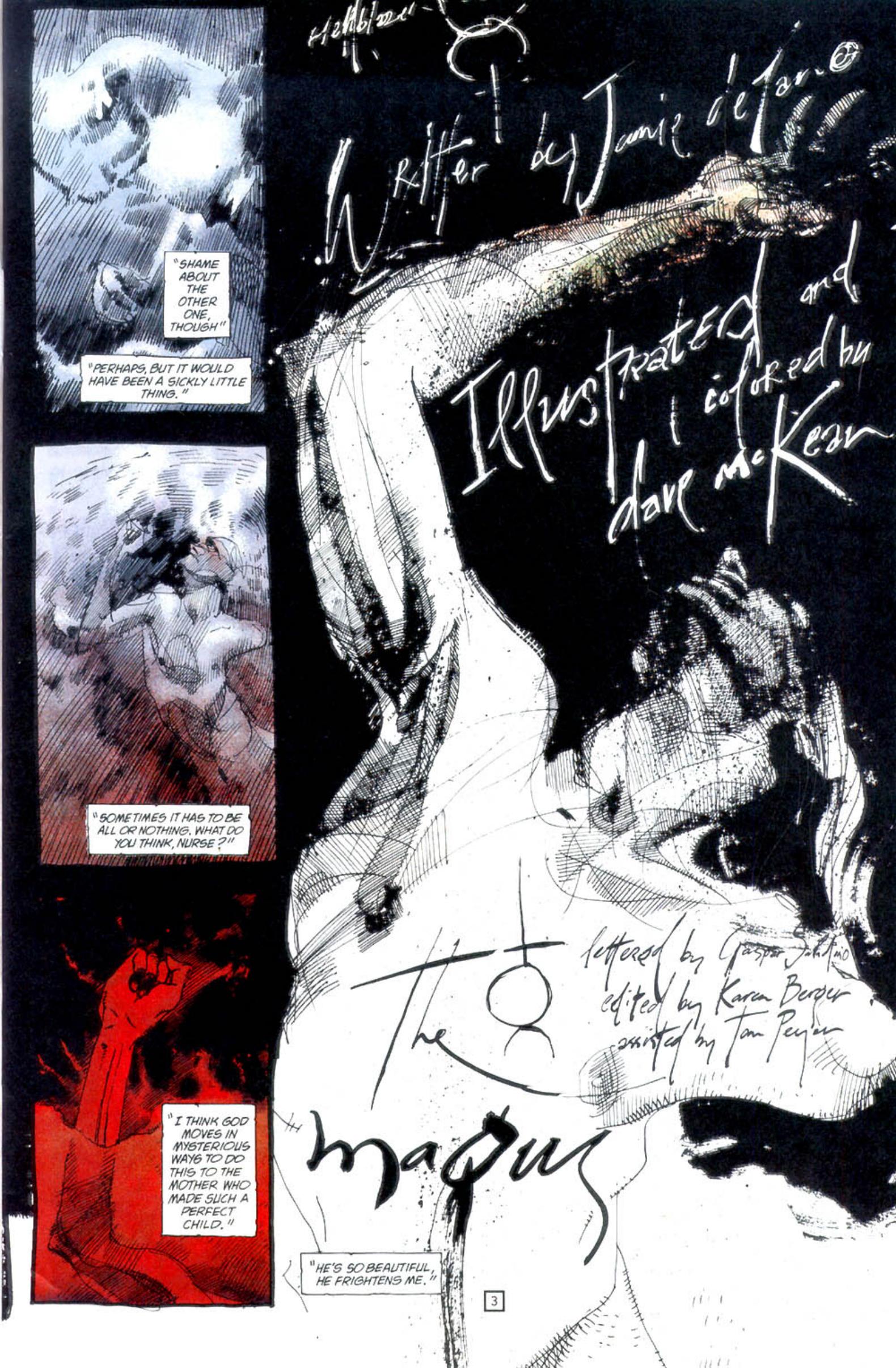

The reason that Veitch at least temporarily wrote Constantine out of his series three issues in was simple enough: Constantine had his own series to star in. This was given the arbitrary but vivid title Hellblazer, and was written by Jamie Delano. Delano was a fellow Northampton native and teenage friend of Alan Moore’s who remained close with him. Delano had long had an ambition to be a writer but, in his words, was instead “just fucking about, getting stoned and driving my taxi, bored and frustrated with the world and most of the people doomed to inhabit it” when Alan Moore, in an attempt to kickstart his old friend’s creative interests, offered to put him in touch with some contacts.

This led to a variety of writing gigs, most of them engineered by his friend and mentor. He took on the Night Raven text pieces in The Daredevils after Moore gave them up, then did a stint writing Captain Britain for Alan Davis to draw once Moore left that title, and finally penned a D.R. & Quinch strip for 2000 AD in which everybody’s favorite interplanetary sociopaths penned an agony aunt column. And when DC expressed interest in doing a book to pick up on the growing popularity of John Constantine, Moore was quick to give his friend another boost.

Where Delano had struggled with many of his early assignments, notably frustrating Alan Davis when they worked together on Captain Britain (Davis complained later that “Jamie had no background or pior interest in the comic form,” and claimed to have been “initially supplying plots and long story, then mutilating and reworking Jamie’s scripts.”), Hellblazer turned out to be a near-perfect fit for him. It is not that the run is a flawless classic of comics—Delano’s work has consistent deficits in plotting and is prone to failures to clearly communicate information to the reader. The practical result of this is that the big moments of his stories rarely quite land, generally feeling unearned or muddy. At various points within Hellblazer this becomes more or less of a problem, but at no point is the run entirely free of it. This means that over thirty-seven issues, Delano never produces one that straightforwardly stands up as a brilliant classic. Many are good and at worst only a handful are bad, but he is simply not the sort of writer that writes singular and imperious works of what is popularly called genius.

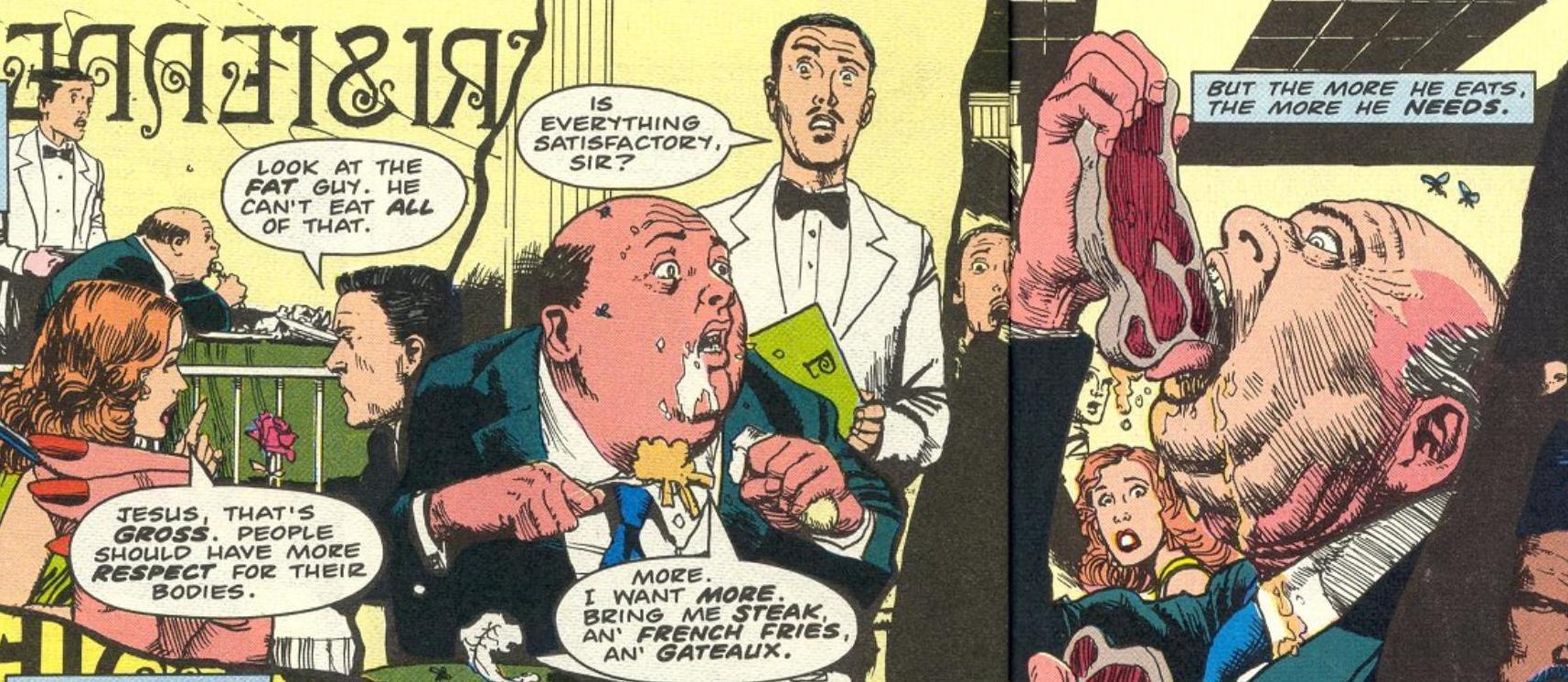

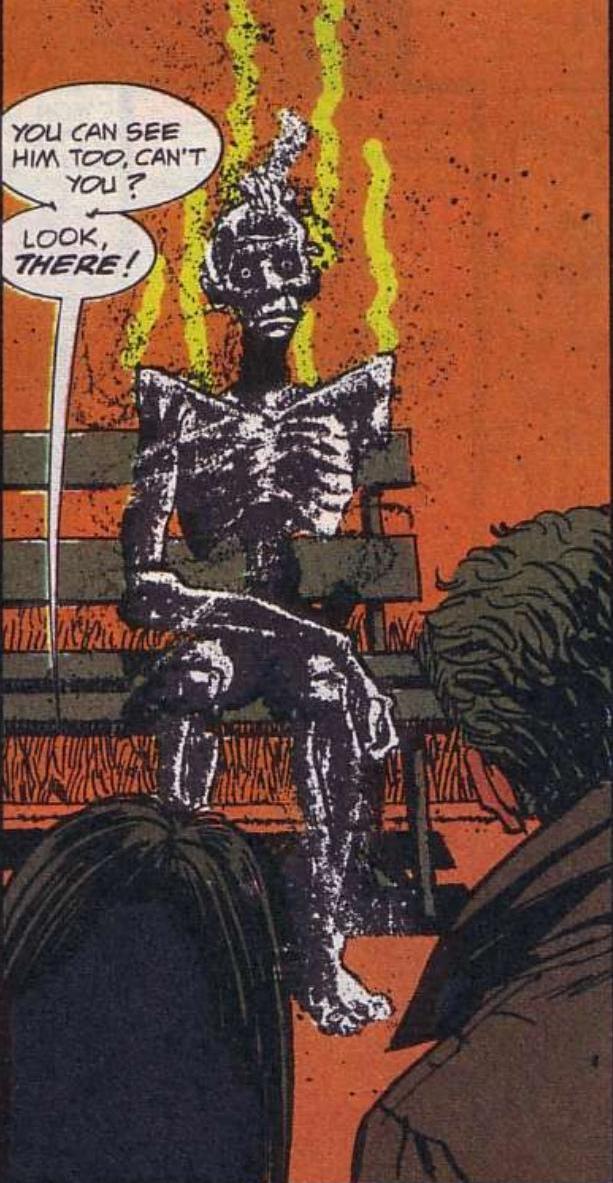

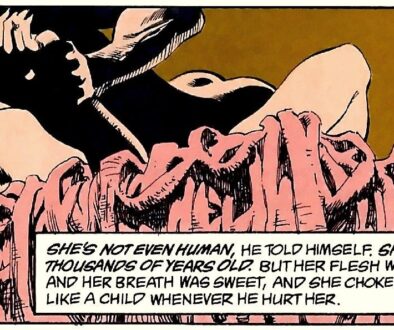

Delano’s run instead succeeds through a rigorously applied aesthetic. Delano’s Hellblazer is a work of dark horror with a furiously leftist sensibility and a gaze focused firmly on the ragged underbelly of the world. It sets out its stall in its first two issues with a story in which one of John Constantine’s friends from the oft-mentioned and ominously teased Newcastle incident shows up in his apartment having accidentally unleashed a dangerous demon named Mnemoth. The story is not without issue—a heavy reliance on dark magic from rural Sudan and a large dose of the fetishization of Haitian Vodou that was trendy in the late 80s/early 90s both ensure that it has aged poorly in key regards. But its high points still crackle with the same imperious vividness that they did in 1987. The opening three pages of issue #1, for instance, feature a man consumed by a compulsive hunger, stuffing multiple hamburgers in his mouth as he stumbles to an expensive restaurant where he begins to eat whole steaks before, overcome, he begins to grab at other diners’ meals, the table settings, and finally the other diners themselves before collapsing into an emaciated husk.

It’s a sequence of bleak and unsettling horror, taking the central image of the Mr. Creosote sketch from the then-recent Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life and inverting it into an impossible and absurd outcome played for no laughs whatsoever. Similarly, the resolution of the first story at the end of issue #2, as Constantine callously sacrifices his friend to stop the demon, a payoff that Delano plays not as a surprising twist but as the grimly inevitable and dreaded outcome built to over two issues in which it’s perfectly clear that Constantine is manipulating and using his drug-addicted friend.

But while these sequences are tremendous, there is none of the intricacy of construction or breathtaking originality that characterizes Alan Moore’s work here—none of the glistening poetry or jaw-dropping turns of phrase that set Moore apar from everyone around him. When Delano shifts into an elevated register, it’s functional but unmemorable—his captions as the man gorges himself to starvation, for instance, include a sequence where he writes, “a whole herd of burgers—hooves and all—couldn’t fill the gaping beak of the giant fledgling that cries inside him. He lumbers through the early evening streets, scattering wrappers behind him, like small carcasses. All is subordinate to his primal urge for food.” It’s evocative, but far from precisely honed, The invocation of eating hooves carries a visceral horror, but it’s undermined by the juxtaposition with “burgers,” the preparation of beef that is furthest from the carnal reality of an entire bovine carcass, and subsequently by the odd veer from mammals to birds and the oxymoron of “giant fledgling.”

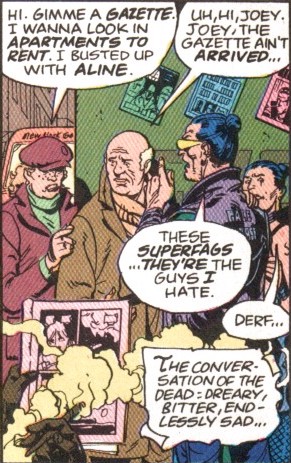

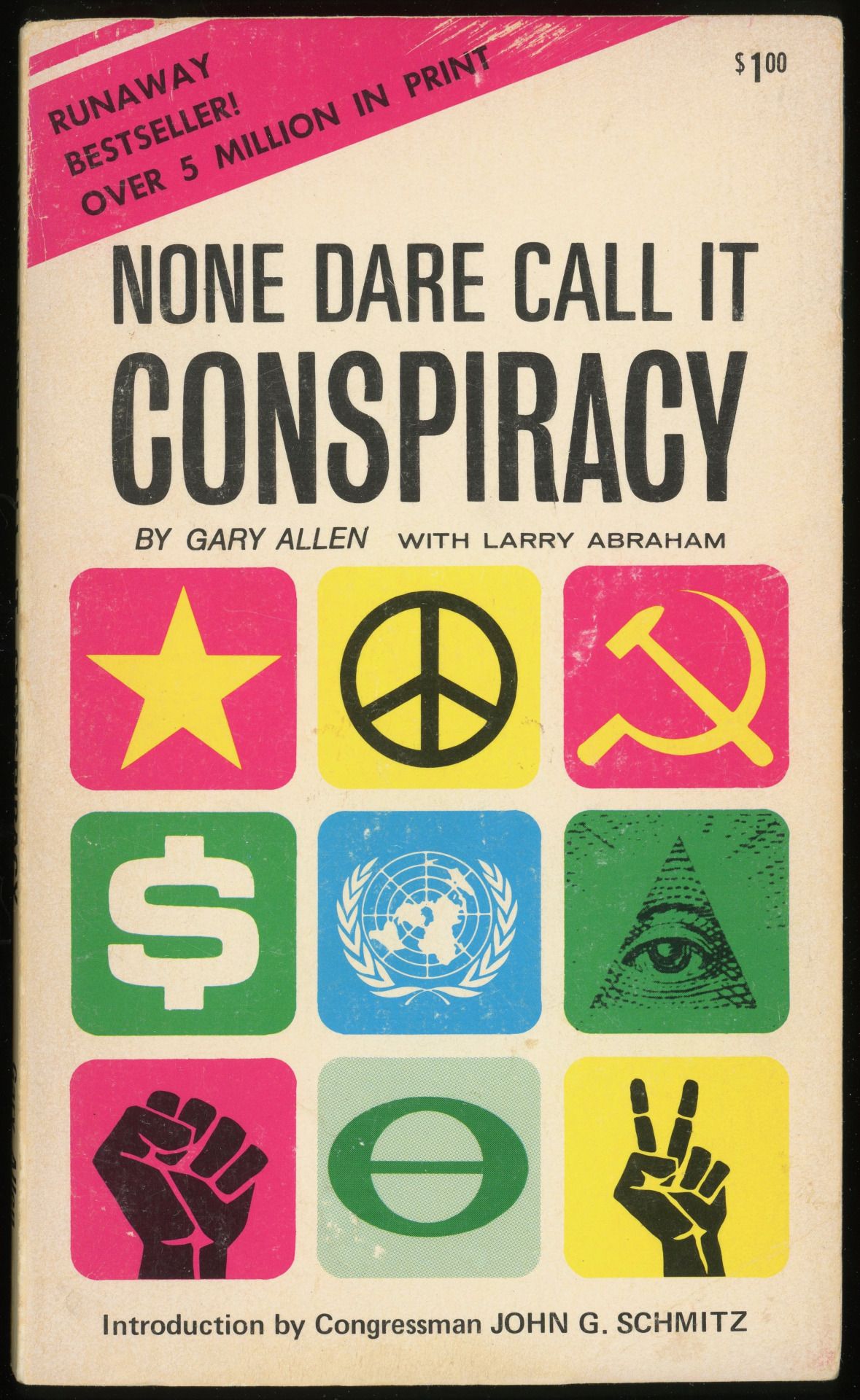

What there is, however, is an unrepentantly swaggering sense of attitude that doesn’t need a flawless execution to land. Within the early issues of Hellblazer, this is best exemplified by Hellblazer #3, which is set on the day of Thatcher’s reelection to a third term in 1987. In it, Constantine investigates the death of a bunch of yuppies and stumbles upon a demonic investment ring buying yuppy souls because the prospect of a Tory victory is creating a bull market. It’s a bitterly funny issue in which the fact that Delano never quite gets around to explaining how the price of souls is impacted by politics, reducing it to a handwave about how “the political climate’s perfect for them. Profit is definitely the top god of the eighties—for monetarism, read Satanism. I bet the upwardly mobile have been queuing to sell their souls,” is almost entirely irrelevant in the face of the fact that demonic investors making loans with the souls of yuppies as collateral and then violently repossessing them is such a brashly hilarious and pointed concept that it would be hard work to do it poorly. Likewise, the plot beat in Hellblazer #6 in which Constantine convinces a demonic assemblage built out of the bodies of a gang of racist skinheads by pointing out that one of their arms has an Arsenal tattoo and another has one supporting Chelsea, resulting in them violently tearing themselves apart is such a great bit of satire that the larger plot it fits into doesn’t really matter. The reader forgets the bits that don’t make sense and instead vividly remembers the clever concepts, which, in point of fact, a generation of comics fans have.

This is not damnation with faint praise; it’s simply a different way of doing things than Alan Moore’s approach. And it has its merits: nobody has ever accused Jamie Delano of “strutt[ing] into view with his blue cock on proud display” or “beg[ging[ for our attention at every page turn.” Delano’s Hellblazer would be diminished if it were as ostentatious and insistent on having its genius recognized as Moore’s best work. It works because it is present, immediate, and furious, not because it is seized with mad ambition. And more to the point, it works because this suits John Constantine, who, in Delano’s conception at least, is not a figure of grandiose and well-worked plans. It is impossible to imagine Delano’s John Constantine engaging in the vast manipulation of Swamp Thing over the course of the American Gothic arc of Swamp Thing. Delano’s Constantine is a man constantly at the end of his rope, only ever succeeding with his last and most desperate scheme. He is a self-destructive alcoholic who at best pushes people away, at worst treats them as objects to be used in his games. A book of ragged fury is what suits this, and it’s frankly a good deal more entertaining than a monthly slab of Moore’s obnoxiously clever master manipulator would be.

This is not damnation with faint praise; it’s simply a different way of doing things than Alan Moore’s approach. And it has its merits: nobody has ever accused Jamie Delano of “strutt[ing] into view with his blue cock on proud display” or “beg[ging[ for our attention at every page turn.” Delano’s Hellblazer would be diminished if it were as ostentatious and insistent on having its genius recognized as Moore’s best work. It works because it is present, immediate, and furious, not because it is seized with mad ambition. And more to the point, it works because this suits John Constantine, who, in Delano’s conception at least, is not a figure of grandiose and well-worked plans. It is impossible to imagine Delano’s John Constantine engaging in the vast manipulation of Swamp Thing over the course of the American Gothic arc of Swamp Thing. Delano’s Constantine is a man constantly at the end of his rope, only ever succeeding with his last and most desperate scheme. He is a self-destructive alcoholic who at best pushes people away, at worst treats them as objects to be used in his games. A book of ragged fury is what suits this, and it’s frankly a good deal more entertaining than a monthly slab of Moore’s obnoxiously clever master manipulator would be.

This, then, was DC’s initial attempt, as conceived by Moore’s two handpicked successors, were these two comics: a surprisingly competent imitation of Moore, and a burst of dark and ragged fury. Neither were quite adequate, giving DC the sort of bankable auteur figure that Moore had become. And even as they debuted, efforts were ongoing to find someone who could serve as a true successor. Karen Berger made a series of trips to the UK in part to scout new talent, including one in February 1987 the month after Moore made up is mind to stop working for DC. These trips would bring many familiar names to the US market, most obviously Grant Morrison and Neil Gaiman, whose debuts came about a year and eighteen months into Veitch’s run respectively, and who each had brief intersections with Delano’s Hellblazer and, in Gaiman’s case, Veitch’s Swamp Thing.

This, then, was DC’s initial attempt, as conceived by Moore’s two handpicked successors, were these two comics: a surprisingly competent imitation of Moore, and a burst of dark and ragged fury. Neither were quite adequate, giving DC the sort of bankable auteur figure that Moore had become. And even as they debuted, efforts were ongoing to find someone who could serve as a true successor. Karen Berger made a series of trips to the UK in part to scout new talent, including one in February 1987 the month after Moore made up is mind to stop working for DC. These trips would bring many familiar names to the US market, most obviously Grant Morrison and Neil Gaiman, whose debuts came about a year and eighteen months into Veitch’s run respectively, and who each had brief intersections with Delano’s Hellblazer and, in Gaiman’s case, Veitch’s Swamp Thing.

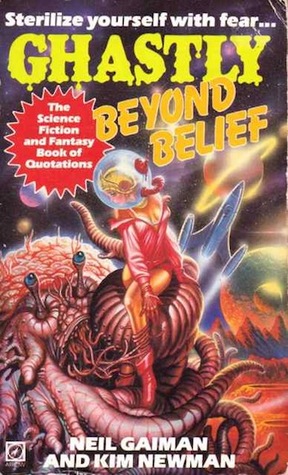

(A comprehensive introduction to Neil Gaiman, who serves as a major combatant in the War and indeed one of its primary victors, is beyond the scope of this particular moment in its history. In short, however, Gaiman befriended Alan Moore after sending him a copy of Ghastly Beyond Belief, a compilation of absurd quotations from science fiction, which delighted Moore.

In the course of their friendship, Gaiman served as a minor research assistant on Watchmen starting with issue #3, when he was able to identify for Moore where the line “shall not the judge of all the Earth do right” originated so that it could be used as the issue’s epigraph. He subsequently contributed quotes for issues #7 [“I am a brother to dragons, and a companion to owls. My skin is black upon me, and my bones are burned with heat.”] and #8 [“On Hallowe’en the old ghosts come about us, and they speak to some; to others they are dumb”] and the Rameses quote used by Ozymandias in the text of issue #12. For this Gaiman was gifted the original art for one of the pages of Dan’s nuclear sex dream in issue #7 and given a thanks credit in the trade paperback alongside Pat Mills, Joe Orlando, and Mike Lake.

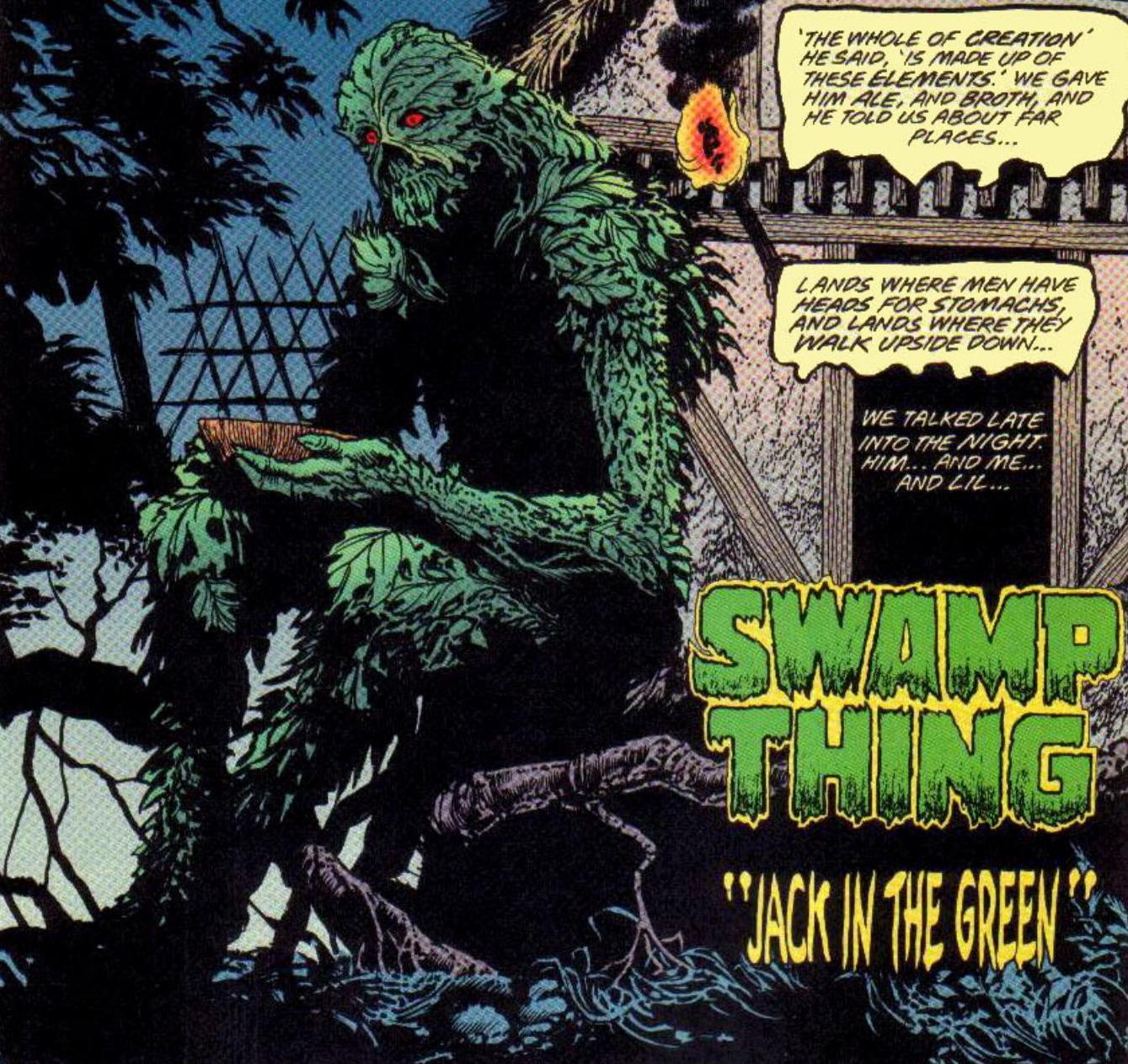

Moore also instructed Gaiman in how to write a comics script, guiding him through two short trial pieces, a John Constantine story in which Constantine confronted the terrible monster that had grown in his fridge while he was off helping Swamp Thing stave off the apocalypse, which Moore was amused by but felt the ending didn’t work, and a Swamp Thing story entitled “Jack in the Green” featuring a medieval version of the character, which Moore liked better, and which Gaiman ultimately used as an audition piece along with his still in progress Dave McKean collaboration Violent Cases when Karen Berger came calling in early 1987. [The story eventually saw print in the 1999 Midnight Days collection with newly commissioned art by Moore’s Swamp Thing team of Bissette, Totleben, Wood, and Costanza.] Between the strength of his work and a recommendation from Moore, Gaiman was swiftly snapped up by Berger.

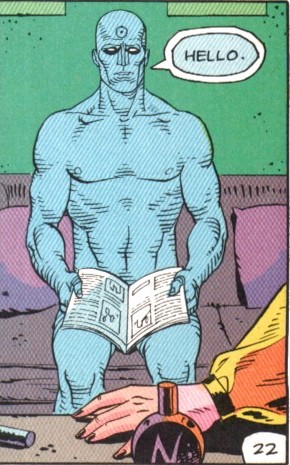

Gaiman’s US debut was a Black Orchid miniseries with his frequent collaborator Dave McKean, followed a few weeks later by his first ongoing series, Sandman, about which much more later. That debuted the same week as Swamp Thing #82, the first issue of Veitch’s final Swamp Thing arc. With Veitch on his way out, Berger decided to hand the book over to Gaiman and Hellblazer writer Jamie Delano, who would each script six issues a year. This plan spectacularly failed to work out, but at the time of its failure Gaiman had already been contracted for Swamp Thing Annual #5, where he penned two stories. The main story was entitled “Brothers,” and saw Gaiman reviving the deeply obscure 1960s character of Brother Power the Geek.

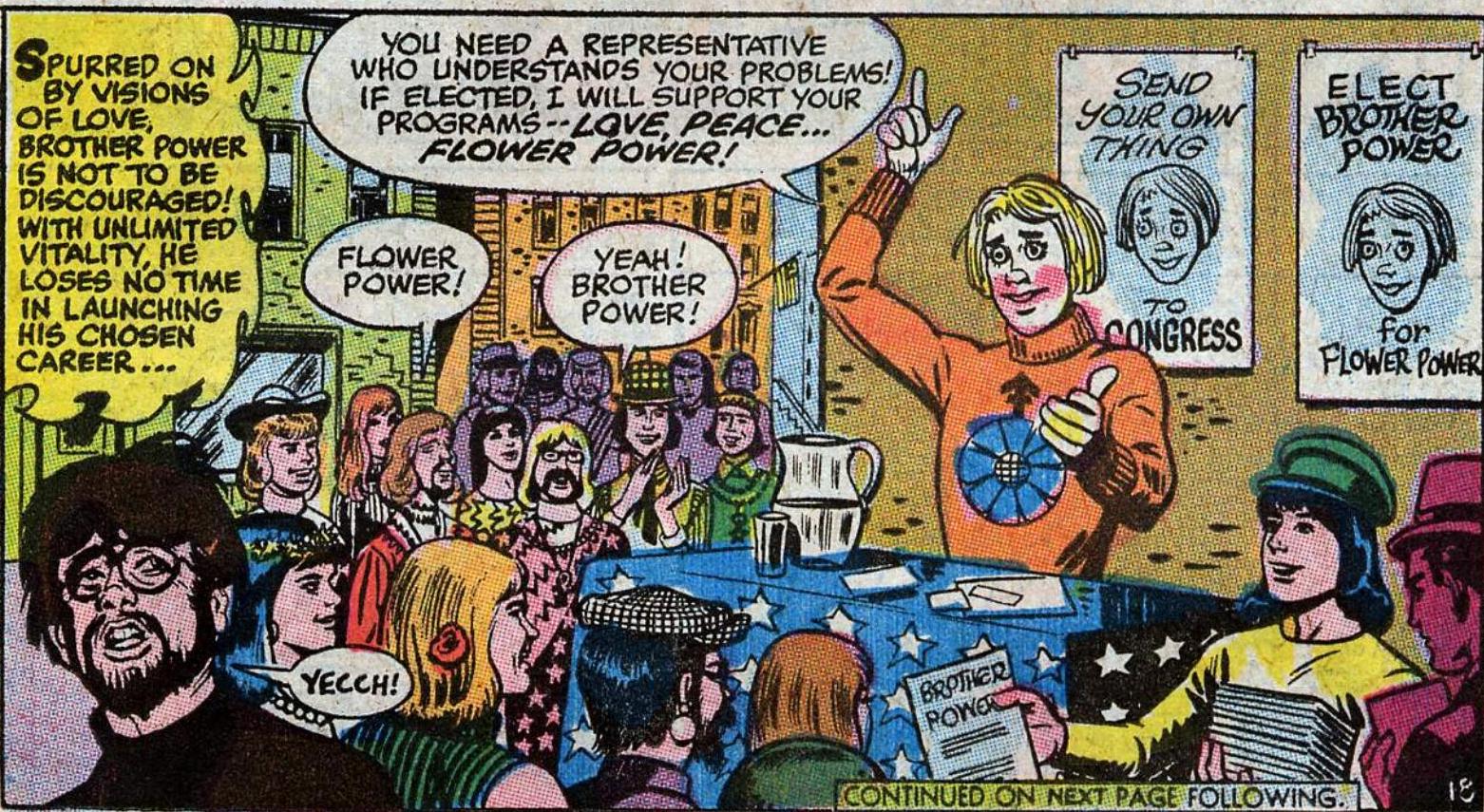

Brother Power the Geek was the subject of a two-issue series in 1968 by Joe Simon with uncredited art work by Al Bare, once described by Alan Moore as “one of the most brain-blisteringly awful comic books ever produced by human beings.” A tailor’s dummy animated by a lightning strike, Brother Power was essentially an effort to cash in on the hippie subculture—after being animated he’s raised by a group of hippie squatters who teach him to speak and send him to school because “he’ll have a bad trip without an education.” The comic straddles a strange line between affection and contempt for and the hippies. They’re straightforwardly the good guys, helping rescue Brother Power when he’s kidnapped by the Psychedelic Circus and chained up as part of their freakshow, but they’re also clearly mocked—they do so after proclaiming that “we’ve got to turn on and be like activists, man! Like, charge in with our trusted lances” and then attacking with a mop and a shovel. But this ambivalence was not enough to spare the comic from the wrath of the legendarily unpleasant Superman editor Mort Weisinger, whose hatred for hippies was apparently so intense that he single-handedly convinced publisher Jack Leibowitz to cancel it after two issues, leaving Brother Power stranded on a cliffhanger ending in which he was launched into space.

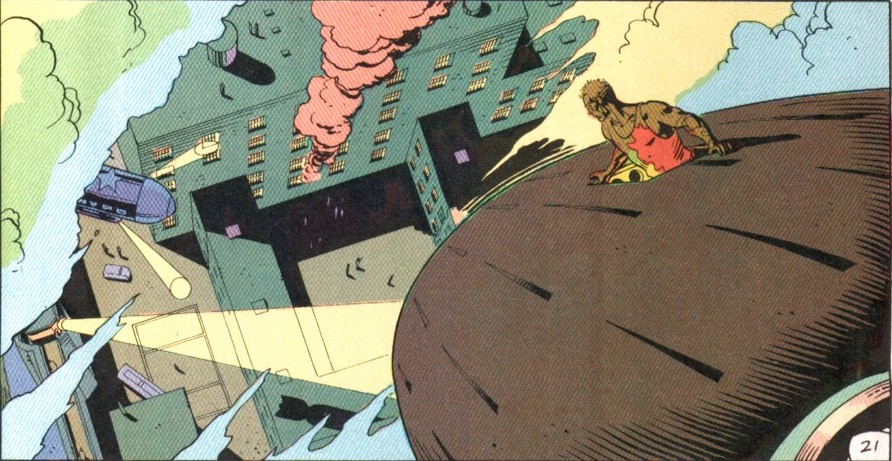

And this is where Gaiman picked him up twenty-one years later, with the satellite upon which Brother Power is trapped crashes into Tampa despite the efforts of Firestorm to prevent it. Amidst the chaos and carnage emerges Brother Power, who ambles around terrifying people for a bit until Chester, the hippie character who’d been clanking around Swamp Thing’s supporting cast since about halfway through Alan Moore’s run, finally talks him down. Along the way Brother Power’s origin is retconned into being a failed “puppet elemental,” thus tying him loosely into the larger Swamp Thing mythos. But for the most part the story is about hippie subculture, its failure and decline, and Chester’s nostalgia for it. Its dramatic center is a pair of conversations Chester has, the first with a black-suited government operative who scornfully explains that he used to be a hippie, but that he woke up with one day in 1968 and “had malnutrition and venereal crabs and I dodn’t know the real names of the last half dozen chicks I’d balled… I looked for my buddies and found that some of them had slipped out of sight. Freak-outs had become crackups and breakdowns and write-offs.” Chester meekly protests that although he was too young to be there, he’s talked to people and knows there was magic to it, and that people still believe, but the agent scoffs, pointing to the failure of any of the things dreamed of by the hippie movement to manifest, then dismisses Chester, saying “I saw all the flower children gone tow eed and seed and thorn. Get out of here, hippie. You make me sick.” From here, however, Chester encounters Brother Power, who he persuades to “cool it with the big bods” and instead wander around and try to “discover the real America,” on the way confessing his knowledge that his romantic relationship with Liz Tremayne can’t possibly endure.

It’s a reasonably effective story that demonstrates a deft understanding of how to use the medium, although it’s clear exactly where that understanding came from. The story is littered with narrative caption boxes repeating a standard formula: “There was a man who tried to do more good than bad, born out of his time.” “There was a woman who had been damaged, tentatively trying to recreate herself through love.” “There was a man who was no longer a man. His humanity had been burnt away long since; and the heart that blazed inside him was a heart of flame, if it was a heart at all.” The debt to Alan Moore’s use of the Justice League early in his Swamp Thing run, where he introduced them with “There is a house above the world, where the over-people gather. There is a man with wings like a bird. There is a man who can see across the planet and wring diamonds from its anthracite. There is a man who moves so fast that his life is an endless gallery of statues…” Gaiman admits as much, noting that “the voice in the caption boxes in ‘Brothers’ is me doing a good-natured if not entirely successful Alan Moore impression. It seemed appropriate: it had been his comic, and he had given it a voice.”

But the debt to Moore runs much deeper than just nicking his caption boxes. Gaiman’s basic approach to the story—taking a character that had at best been forgotten and at worst was widely regarded as a joke and revamping it for the present day by finding a new interpretation of its origin—is a carbon copy of what Moore did with Swamp Thing himself. And this, in turn, is what Moore had done with Marvelman back in Warrior, the gig that put him on Len Wein’s radar in the frist place. This is not a coincidence; it was exactly what Karen Berger was looking for when she went to the UK to take pitches. Gaiman recounts their 1987 meeting: “So I did my pitch for Phantom Stranger and they said, “Weirdly enough, Grant Morrison was in this morning, he did a pitch for Phantom Stranger too. Yours is really good, his is really good—unfortunately we’ve got this Paul Kupperberg piece, which is not very good but it is what he is. So you can’t do that.’” So Gaiman proceeded to pitch more characters, both relatively mainstream ones like Green Arrow and Black Canary and deep cut obscurities like Nightmaster, Klarion the Witch Boy, and Cain and Abel before finally getting to Black Orchid, a character Berger didn’t even know who was. This was, in other words, the specific format that writers imported from the UK were expected to hew to. It was what Grant Morrison would do with Animal Man, what Peter Milligan would do with Shade, the Changing Man, and, albeit to a far more radical extent, what Gaiman did on Sandman.

But it is this last example that is ultimately most revealing. The project upon which Gaiman’s reputation and career was built was the one in which he strayed furthest from the tidy “revise some old crap no one cares about into a mature readers title” brief that he and everyone else in the initial post-Moore wave of imports was given. An ability to copy the formula worked out by Alan Moore may have been what got Gaiman, Morrison, and their contemporaries their first gigs in American comics, but those who thrived did so by copying a more fundamental skill of Moore’s: doing something no one had ever thought of before.)

Until then, Veitch and Delano had to fill the gap, defining the brand of “the stuff DC does that’s like Alan Moore.” For Veitch’s part, he began a storyline exploring the consequences of Swamp Thing’s unborn successor. In it, the sprout (as it is often referred to) attempts to incarnate in a number of bodies and, for a variety of reasons, fails. This is the nominal reason for the Swamp Thing/Solomon Grundy fight in issue #67—the sprout attempts to bond with Grundy and ends up being drawn into Grundy’s madness and becoming violent.

Until then, Veitch and Delano had to fill the gap, defining the brand of “the stuff DC does that’s like Alan Moore.” For Veitch’s part, he began a storyline exploring the consequences of Swamp Thing’s unborn successor. In it, the sprout (as it is often referred to) attempts to incarnate in a number of bodies and, for a variety of reasons, fails. This is the nominal reason for the Swamp Thing/Solomon Grundy fight in issue #67—the sprout attempts to bond with Grundy and ends up being drawn into Grundy’s madness and becoming violent.

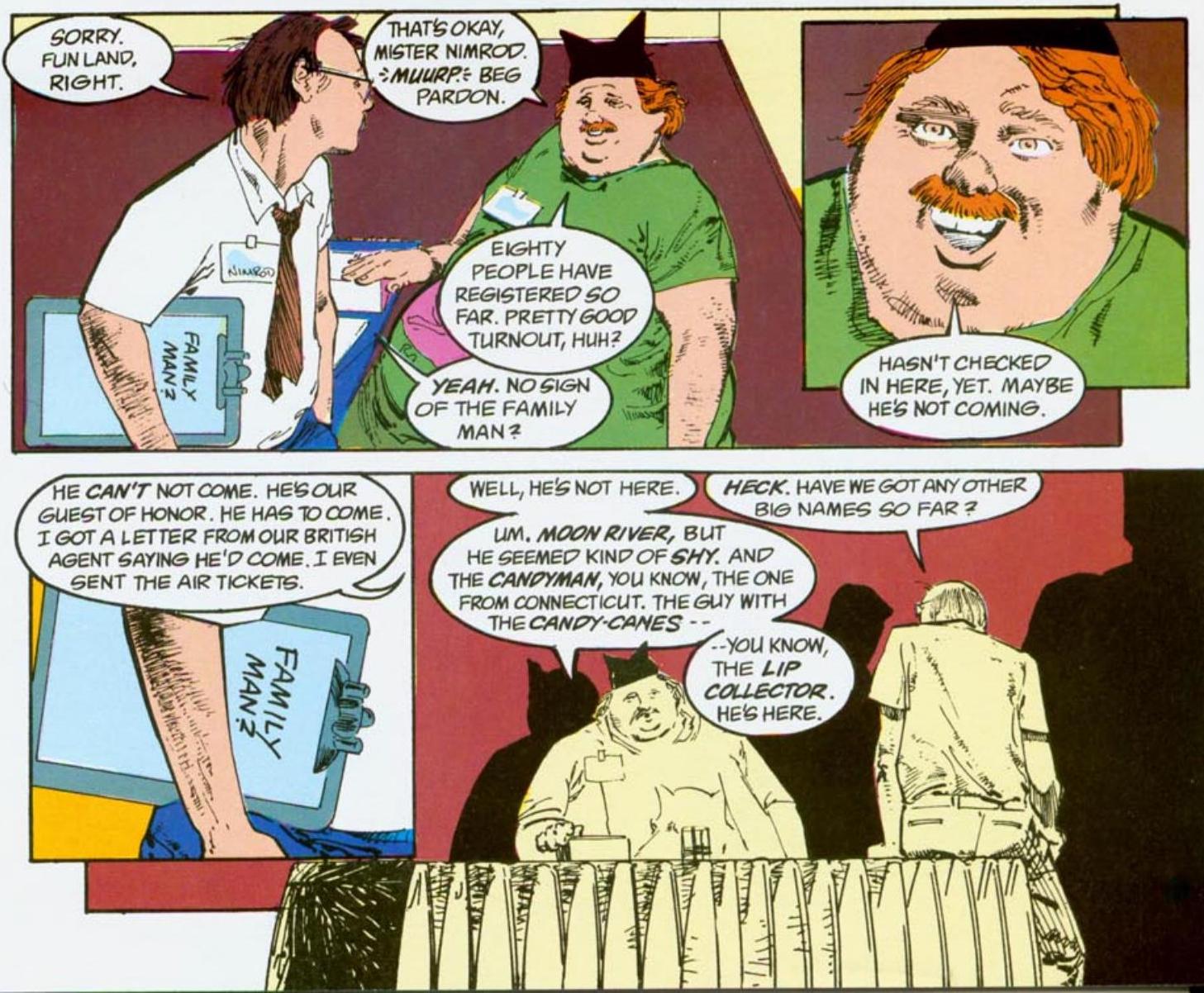

(Towards the end of 1989, in a gap in the midst of Delano’s The Family Man arc, Hellblazer #25 and #26 were released, telling a two-issue story penned by Grant Morrison with art from David Lloyd. Morrison was by this point nineteen issues into Animal Man, ten into his Doom Patrol run, and perhaps most crucially, a month past the release of Arkhm Asylum. He was, in other words, well-established as a hot new talent at DC, while for Lloyd this was his first post-V for Vendetta project. It was, in other words, not a random tossed-away fill-in issue, but a team-up of two leading lights of the by then clearly in progress British Invasion of comics who had never worked together before. [Indeed, this is Morrison and Lloyd’s sole collaboration.]

(Towards the end of 1989, in a gap in the midst of Delano’s The Family Man arc, Hellblazer #25 and #26 were released, telling a two-issue story penned by Grant Morrison with art from David Lloyd. Morrison was by this point nineteen issues into Animal Man, ten into his Doom Patrol run, and perhaps most crucially, a month past the release of Arkhm Asylum. He was, in other words, well-established as a hot new talent at DC, while for Lloyd this was his first post-V for Vendetta project. It was, in other words, not a random tossed-away fill-in issue, but a team-up of two leading lights of the by then clearly in progress British Invasion of comics who had never worked together before. [Indeed, this is Morrison and Lloyd’s sole collaboration.]

This was at least a mildly ironic assignment for Morrison, whose comments on Hellblazer around the time were generally backhanded—in a 1989 interview in Fantasy Advertiser he’d proclaimed, “ I like Hellblazer except when it’s being ‘moral’, like in the skinhead issue,” while in an interview conducted a few months before the arc came out he said, “I like Hellblazer. I think it got a bit tedious, but it’s picking up again.” He also asserted in the same interviewer that that he was “trying to get Constantine into a dress” in his arc, but that he doubted DC editorial would approve it. In practice, although the comic features John Constantine donning a Margaret Thatcher mask and getting swept away into a dark carnivalesque revelry, he sticks to trousers the whole time.

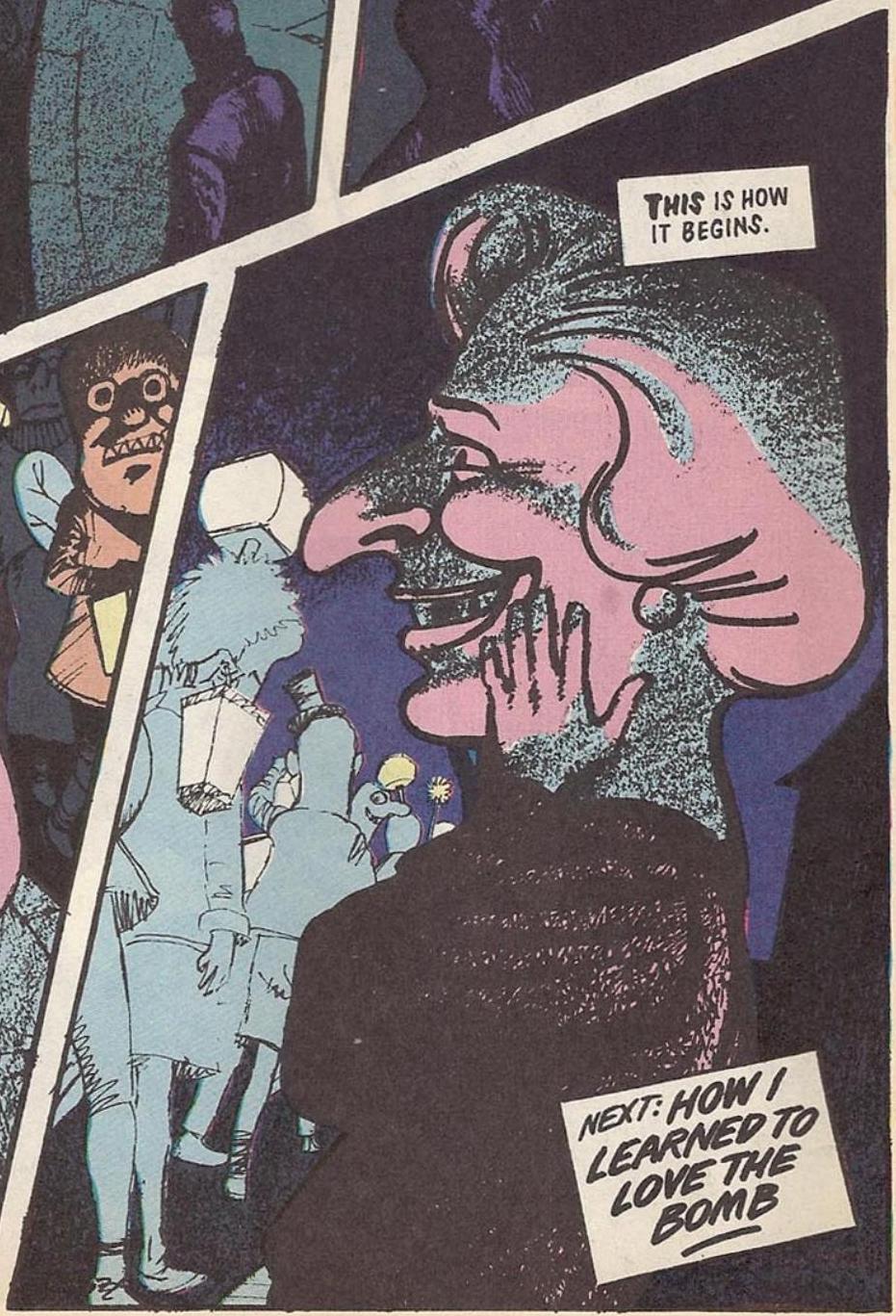

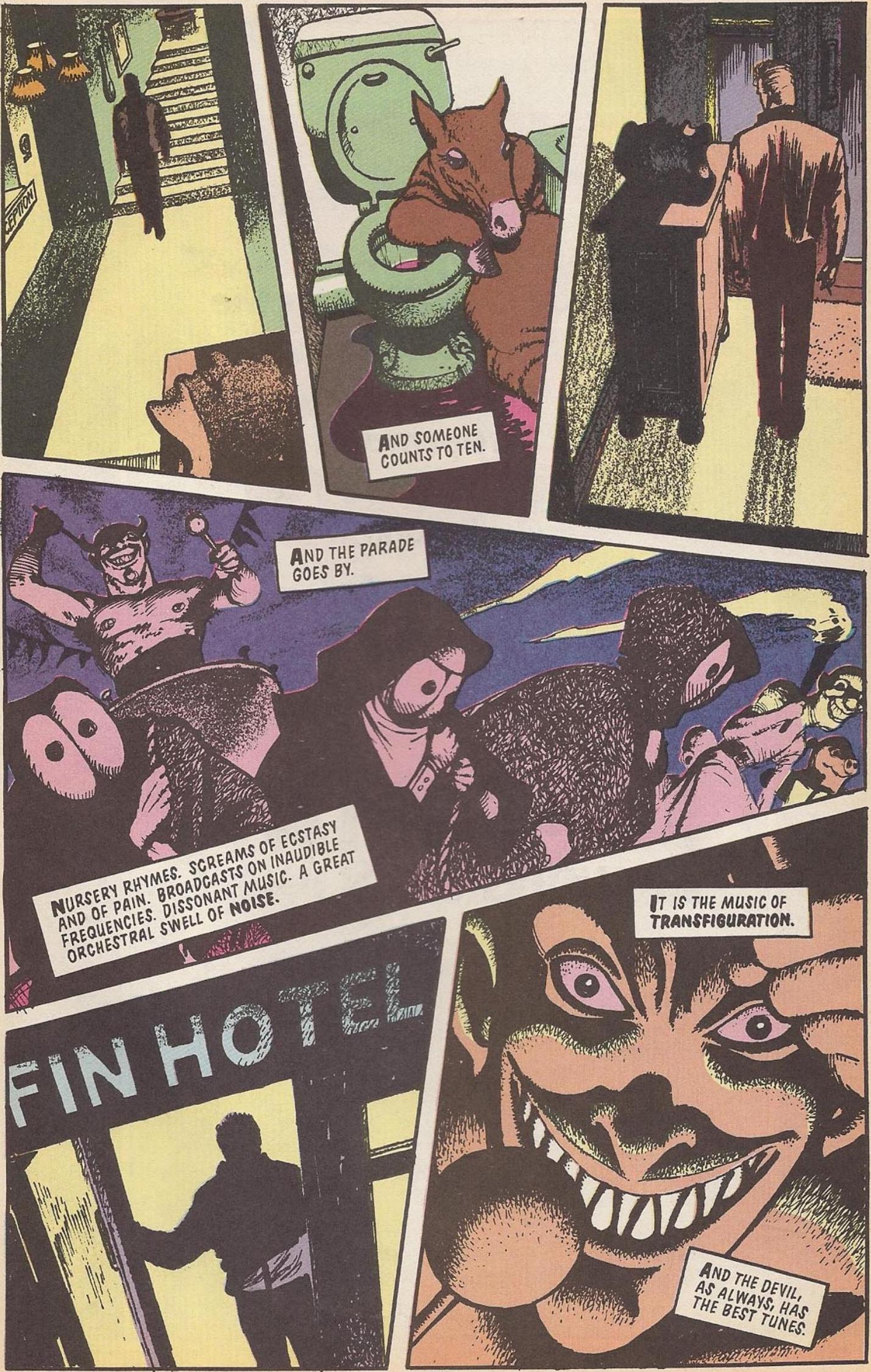

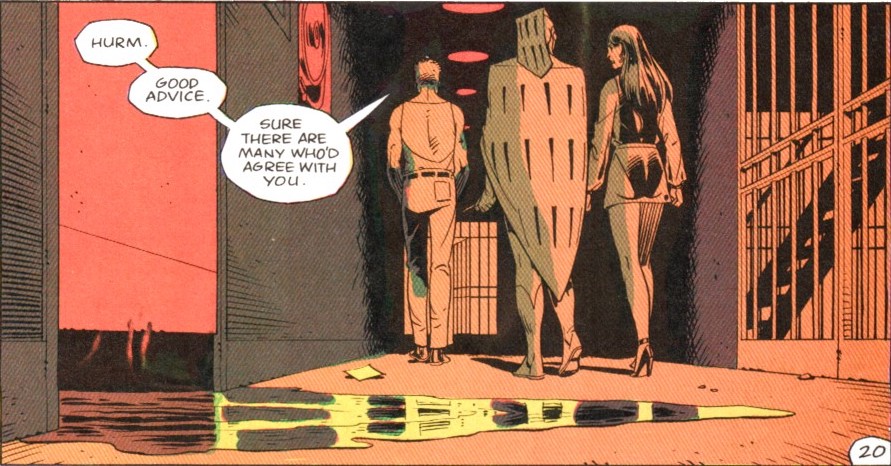

The story, however, was not nearly so comedic as this account suggests. Instead it is a piece of moody dream theater in which the carnival is treated as a surviving remnant of pagan ritual—an upside-down world in which repressed desires emerge from the shadows to take hold as the rational, everyday world takes its turn at being repressed. Lloyd’s art, which, as the carnival takes over the narrative, stops existing in the tight rigidity of square boxes offering variations on the nine-panel grid that he used across V for Vendetta, his panel borders instead beginning to skew and tilt, turning the pages into an unsettling and off-kilter reverie, uses stark and solid blocks of pastel color to dress events in a sense of fitful unreality.

Unsurprisingly for his first real attempt at an unadulterated horror comic, Morrison turns to his own primal horrors. The comic is not quite set in Scotland, but instead in a fictional small village called Thursdyke that Morrison locates simply with a caption box reading “North” [although the first panel image of the early warning radar system at RAF Fylingdales and a bit of dialogue about being “twenty miles from Ravenscar” puts events a little more than an hour and a half south of Newcastle]. The town is down the hill from an American missile base, which, in the wake of Thatcher’s shutdowns of the collieries, has become the town’s primary economic resource.

Constantine comes to town on the invitation of Una, an old friend from his post-Newcastle incarceration in a mental asylum who has suggested he might want to see the carnival parade. The night of the parade, however, Professor Horrobin, a scientist at the base goes deep within the caverns of the base, explaining as he does about “the old stories of mythical kings and giants asleep beneath the earth.” He proclaims that he intends to wake the buried kings within mankind, and that he’s set off a bombardment of “microwaves set to resonate with the ten Hz frequency of the human brain. All those unconscious desires and fears and repressed longings. Set free.”

Within the town there is a mad rush. A man in a baby costume murders his wife for loving their child more than him, then begins to cut his infant child’s fingers off. Another in a dog costume gouges out his dogs’ eyes and sets them to keep watch. And as the first issue ends, Constantine, sucked into the maelstrom, slips on a Margaret Thatcher mask and joins the mob.

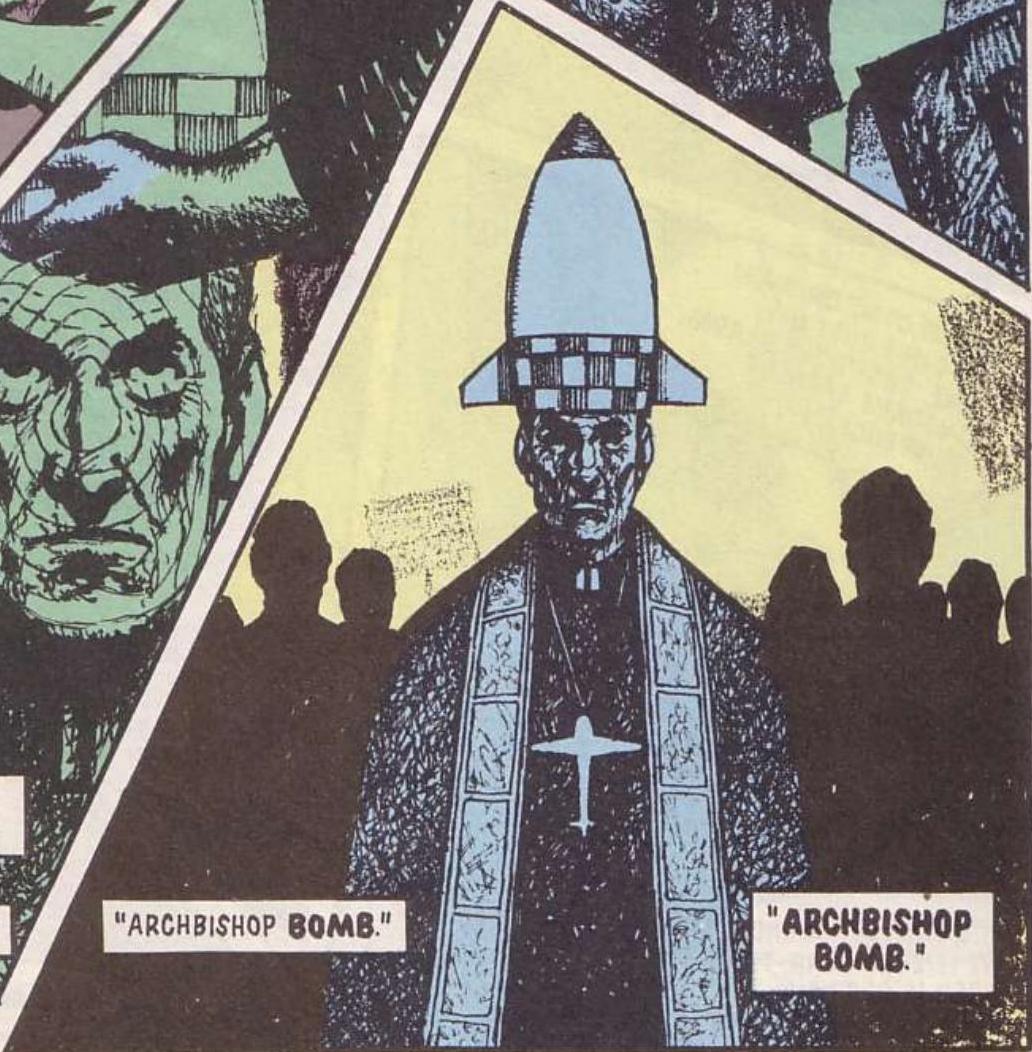

In the second part, meanwhile, the village parson, an old anti-nuclear activist named Bayliss is seized by the mob, held down, dressed, made up and proclaimed the Archbishop Bomb. He leads the mob to storm the RAF base, where it becomes clear that Horrobin’s machine is just an empty box, and that whatever is happening is not caused by anyone. Una, meanwhile, rescues Constantine, who realizes that with its economic collapse under Thatcher the town has psychically died, and that what remains clings to the bomb, which “gives their lives meaning, like a new religion, and now they’ve gone to meet God.” Constantine rushes to the base, but too late, as Archbishop Bomb has stolen one of the jets and drops a bomb onto the village just before the crowd was about to burn Una as an offering to the Nuclear God.

It is, in other words, a quintissentially Morrisonian story, merging his fascination with the unconscious mind [the links between underground complexes and the unconscious are going to reappear in The Invisibles] and his horror at the bomb. And unmediated by the later optimism with which he would uncritically proclaim Superman to be the categorical answer to the atomic bomb, Morrison’s sense of it as a terrifying death god feeding on the corpses of economically devastated towns is an object of genuinely uncanny horror. Indeed, it is a front on which he, in this outing at least, is largely able to outdo Moore, whose horror of the bomb, while self-evidently genuine, always feels more like an intellectual revulsion at the idiocy of men who would create such a weapon than an emotional gut reaction of fear. Morrison, meanwhile, offers a sense of the bomb that feels rooted in a real fear, reaching back to his childhood memories of anti-nuclear pamphlets depicting the blasted and hellish horrors of a post-annihilation world, of his father’s activist friends being disappeared by mysterious men in black, and of how he “used to imagine god was a skeleton and the thunder was the sound of his big, black iron train.”

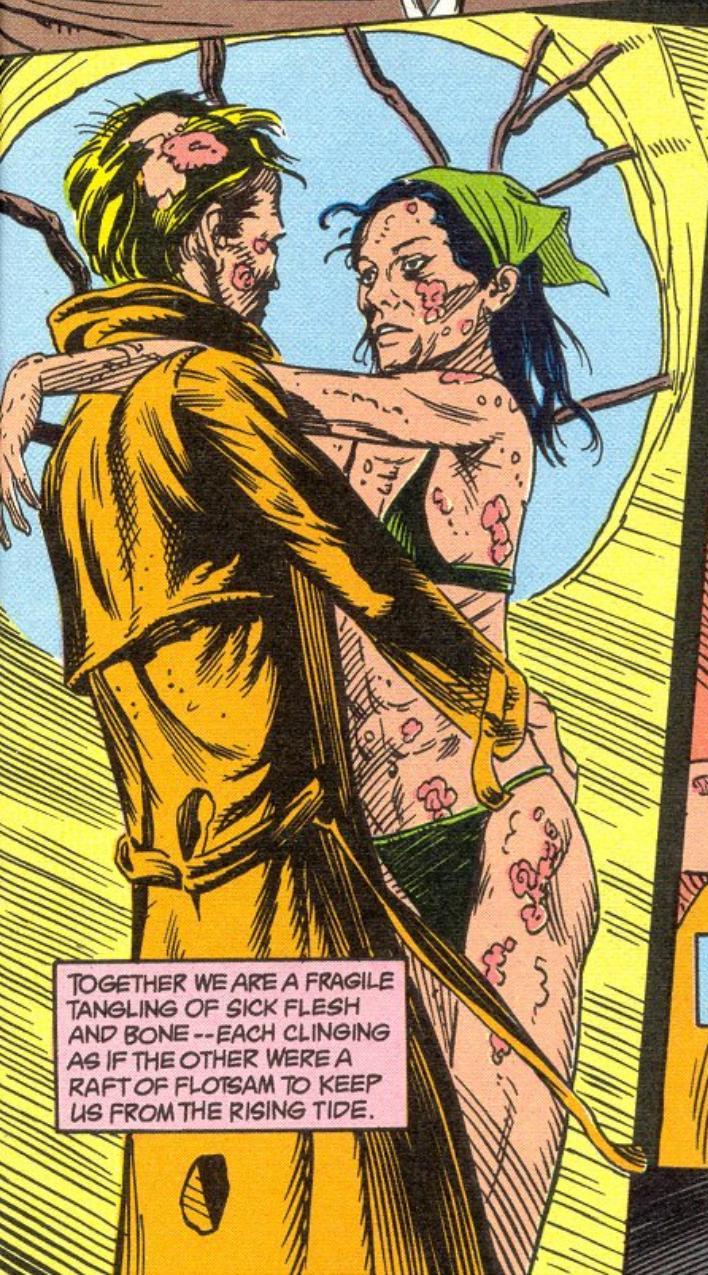

But it’s also a story that slots very smoothly into Delano’s Hellblazer. Its sense of socially conscious horror is squarely in line with what Delano was doing with the book, as is the focus on the abandoned edges of British society under Thatcher. Indeed, Delano did his own anti-nuclear issue of Hellblazer just over a year prior in Hellblazer #13, an issue that is largely consumed by Constantine having a nightmare of nuclear annihilation. Delano’s focus, however, is split between a sense of body horror at images of radiation poisoning—at one point, Constantine dreams of embracing a woman and Delano describes “an emptiness of bruising, sobbing flesh—a body softness wetly smothering a calcium crumbling of teeth”—and a more abstracted concern with the idea of a species-level future and of evolution and mutation. Morrison goes in neither direction, and indeed does not need to retreat into the hyper-symbolic rhetoric of a dream sequence for his horror, finding it instead in the everyday experience of living in a nuclear-threatened world.

This is undoubtedly a strength in Morrison’s work compared to Delano’s. And the comparison is in a larger sense a useful one. Like Delano, Morrison’s strengths often do not lie in plotting or clarity. Indeed, his Hellblazer arc demonstrates that—after the reveal that Horrobin’s machine is actually just an empty box Horrobin somewhat randomly kills himself and the other scientist in a pretty flagrant “well these guys aren’t part of the resolution so let’s write them out of the story” move. More broadly, the “why” of the story never quite adds up—there’s a plot point of using music to block out the effects of the carnival that doesn’t really square away with the idea that there’s not actually a signal producing any of this. And more broadly still, if one widens the lens to Morrison’s career as a whole a tendency to not quite offer enough explanation to fully sell what he’s doing.

And yet Morrison is an appreciably more successful and for that matter more skilled writer than Delano. Much of this comes down to the fact that even if Morrison can be untidy in his execution, his work offers a conceptual coherence that Delano’s often does not. Delano’s nuclear story is composed of essentially arbitrary components. Its title, “On the Beach,” is borrowed from the famed 1959 post-apocalyptic film, but for Delano this is wholly literal—Constantine falls asleep on a beach and has a nightmare about the nucelar apocalypse there. And this dream takes place in a story that’s elsewhere about Constantine’s childhood memories and his propensity for nightmares—both interesting topics, but not ones with an obvious and direct relationship to nuclear armageddon. Morrison, on the other hand, has taken care to ensure that his ideas go together: nuclear apocalypse, post-industrial collapse, and the idea of a sublimated death drive centered on the atomic bomb as a new god makes sense in a way that beaches, nuclear power, evolution, and Constantine’s loss of childhood innocence don’t. Delano also chooses nuclear power as his focus [his hook being that there’s a nuclear power station near this beach], unlike Morrison, who focuses on the more straightforward horror of the atomic bomb.

This is not to say that the ways Morrison is tailoring his style to fit within what Delano is doing don’t improve the story. Morrison is not usually this grounded in social reality—he has no love for Thatcher’s Britain, but his disdain for it is not an animating passion the way it is for Delano. Doing his take on Delano pushes him to do things he wouldn’t have done in other circumstances, and this implicit collaboration is every bit as electrifying as the actual one between Morrison and Lloyd.)

.jpg)

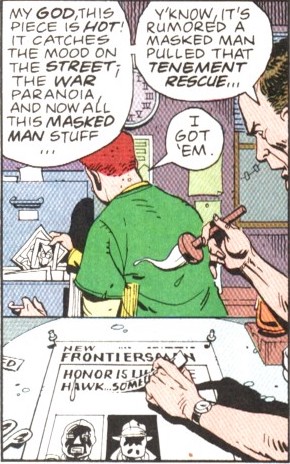

For the most part, Veitch uses this structure to create a number of horror scenarios as the sprout tries and fails to take on a number of hosts. For instance, over the course of issues 68 and 69 it tries to merge with Alan Bolland, a KKK member thrown out of the military for assaulting a superior officer whose favorite film is Taxi Driver and who idolizes James Earl Ray. This results in a crazed and violent Swamp Thing who lurches around spouting advertising jingles, initially staggering out of a swamp towards a derelict truck muttering “you… all that you can be… all the things you do… you keep America working… this beer’s for you!” and later smashing cars on the highway as he explains, “Around here quality is job one. We’ve produced the best cars and light trucks designed adn built in America for six years running. SO HAVE YOU DRIVEN A GODDAMN FORD lately?” It’s a surreal and macabre plot beat reminiscent of the stuff Delano was doing over on Hellblazer, savvily playing with the trope of right-wing militia-style terrorism years before it really picked up steam in the popular consciousness. And after the sprout is separated from this body, it provides one of the highlights of Veitch’s run, a long smoldering subplot in which two sleezebag TV producers are trapped in a car driven by the now vacated body of the would-be Swamp Thing being sped across the country as he babbles a collage of advertising jingles at them.

(Midway through writing “Brothers” for Swamp Thing Annual #5 Gaiman learned of Veitch’s premature departure from the title and the unpleasantness surrounding it. He and Delano were asked to come onto the book early, but refused in solidarity with Veitch. Gaiman, however, still had to finish the annual, which would now come out in the three month gap between issues that Veitch’s departure had created. And so he started in on the ten page backup feature about the Floronic Man, to be drawn by a pre-Hellboy Mike Mignola. The resulting story, “Shaggy God Stories,” sits at a strange midpoint between its original intention and its new context. On the one hand, angry on behalf of his colleague, he changed the focus of the story, emphasizing Woodrue’s status as a fallen angel and cheekily naming the venus flytrap he carries to see the Parliament Milton. On the other, the story kept the basic focus it had always had, offering a collection of ominous teases for Gaiman’s now never to take place run.

(Midway through writing “Brothers” for Swamp Thing Annual #5 Gaiman learned of Veitch’s premature departure from the title and the unpleasantness surrounding it. He and Delano were asked to come onto the book early, but refused in solidarity with Veitch. Gaiman, however, still had to finish the annual, which would now come out in the three month gap between issues that Veitch’s departure had created. And so he started in on the ten page backup feature about the Floronic Man, to be drawn by a pre-Hellboy Mike Mignola. The resulting story, “Shaggy God Stories,” sits at a strange midpoint between its original intention and its new context. On the one hand, angry on behalf of his colleague, he changed the focus of the story, emphasizing Woodrue’s status as a fallen angel and cheekily naming the venus flytrap he carries to see the Parliament Milton. On the other, the story kept the basic focus it had always had, offering a collection of ominous teases for Gaiman’s now never to take place run.

The nature of this run is largely mystery for the simple and obvious reason that Gaiman never actually took the job and so never worked it out in any detail. Nevertheless, several fragments of what might have been exist: a couple of quotes from Gaiman, a planning document entitled “Notes Towards a Vegetable Theology,” and, of course, “Shaggy God Stories” itself. Of these the quotes are the most specific, vague teases of what might have been that they are. The first comes from a 1989 interview, where he hinted at having had plans for Jason Woodrue that involved him “was getting back to being Woodrue, the Rue of the Wood, and probably on a much bigger scale, a much nastier scale. It would have been fun, but again it didn’t happen. I probably would have brought back Black Orchid in there. I don’t know, because as I said, it never got that far.” The second comes in the introduction to “Shaggy God Stories” in the 1999 Midnight Days collection, where Gaiman describes how his run would have “began with the Wolves of the Woods padding out of the forests, thorns on their feet instead of claws.” But as Gaiman notes in the 1989 interview, “it really hadn’t even gotten to the plotting stages.”

“Notes Towards a Vegetable Theology” offers a broader perspective on Gaiman’s potential Swamp Thing ideas, but is in turn far less focused on the actual question of narrative than either of his two cryptic teases. The piece is described as “an unpublished essay,” but it is more accurate to call it a pitch document—something akin to Moore’s “Interminable Ramble” on Twilight of the Superheroes or the Watchmen character breakdowns reprinted in the Absolute edition. Indeed, the comparison to Moore is revealing, as Gaiman is undertaking a very specifically Moorean project here. Just as Moore described his Swamp Thing Annual four years earlier as an attempt to “roughly map out the DC supernatural universe,” “Notes Towards a Vegetable Theology” seeks to “align the various vegetable set-ups within the DC universe, and throw in a few things to make it fun and codifiable.”

That said, Gaiman’s approach is demonstrably different from Moore’s. None of Moore’s publicly released pitch documents, for instance, begins with a lyrical musing in narrative form that starts by quickly recapping Genesis and the opening of Paradise Lost before noting “There was a garden—that much is certain. And in the garden, the first man and the first woman tasted forbidden fruit and were cast out into the world. Their children were a gardener—the first murderer, a slaughterer of animals—and the first victim; the stories continue from there. Did this happen once, or many times? On this planet or another? At the end of time, or, in an infinite inhabited universe, is this happening forever until the last day? On this, as with so many other things, secrets are kept, and mysteries are held.”

There’s a lot going on here, including a deep cut DC reference transitioning from a veiled discussion of Cain and Abel to a reference to secrets and mysteries, The House of Mysteries and The House of Secrets having been a pair of 70s horror anthologies hosted by DC’s versions of the characters. [These ideas, at least, Gaiman would end up using in Sandman instead.] But there’s also a characteristically Gaimanesque attempt to frame all of this in terms of stories and the diversity thereof, switching from Genesis to Norse mythology and the existence of Yggdrasil.

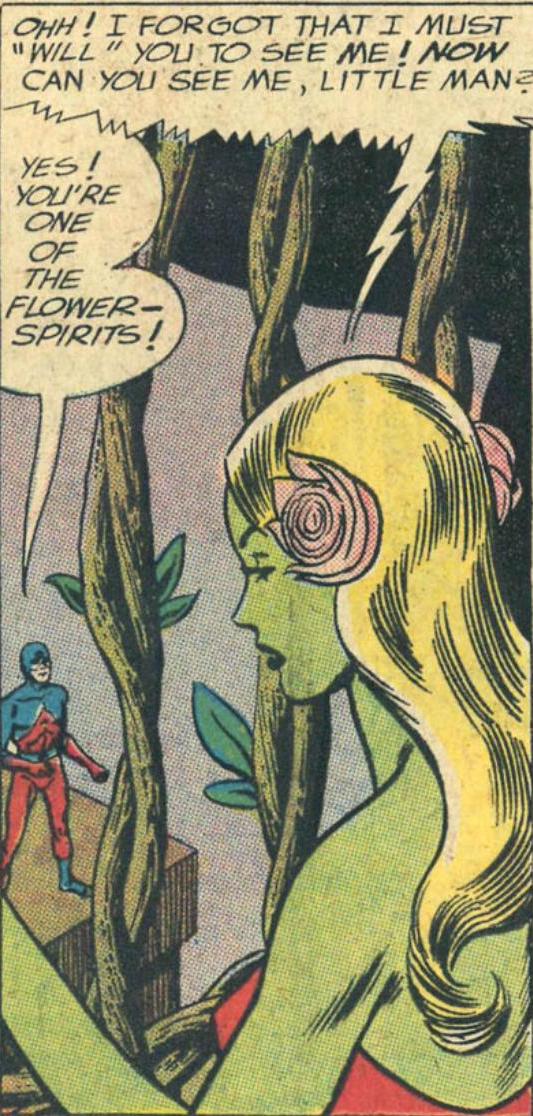

Gaiman moves forward to defining specific Earth-based nature spirits, starting with Gaea, who Gaiman politely suggests should not be equated with the Wonder Woman character or indeed personified at all. Below Gaea, Gaiman positions a number of categories of entities, beginning with the plant elementals, which Gaiman, in a typically mythological move, rechristens the Erl-Kings. As a female counterpart to this he proposes the May Queens, suggesting that their number includes Black Orchid, the pre-Crisis Thorn, and Poison Ivy, who he posts as being “a May Queen that went rotten—like Solomon Grundy is an Erl-King gone rotten.” Beyond these he posits the existence of Dryads, which are “free-floating consciousnesses within the green” that can manifest on Earth in plant form, and Forest Lords, which are the rulers of specific forests. In neither of these cases does Gaiman give any examples [although he makes reference to the pre-Crisis version of the Dryads, an extra-dimensional species from the Silver Age Atom comics from which Jason Woodrue originated], nor were the ideas picked up on by anyone in the way he laid them out.

This leaves “Shaggy God Stories” itself. The story is a simple enough one at ten pages—Jason Woodrue, accompanied by a venus flytrap he bought and named Milton, journeys to visit the Parliament of Trees. There he makes a confused but impassioned speech in which he accuses the Parliament of meddling with humanity in order to give them religion. The Parliament declines to answer, offering only the cryptic warning: “beware the Forest Lords, Woodrue. They turned your mind once.. They can do so again. And beware the corruption of Matango.” The strip ends with a perplexed Woodrue, offended at his dismissal, wandering off trying to find Milton, who he has in fact left besides the Parliament, and whose flytrap mouths smile menacingly at the mention of Matango and the Forest Lords.

In addition to this reference to the Forest Lords, Gaiman works in several other key phrases of his vegetable theology—the Parliament’s mouthpiece refers to them as “the haven of the Erl-Kings,” for instance, and on his way there Woodrue encounters a Dryad named Myra, a reworking of a pre-Crisis character tied into his origin. [He also has Woodrue offer a version of his musings on the possible links between the Tree of Life in Genesis and the Norse Yggdrasil.]

It is far from clear that all of this represents Gaiman’s actual plans. In particular, Woodrue’s speech, which has him accusing the Parliament of having been responsible for creating virtually every major world religion is likely to be Gaiman taunting DC over the circumstances of Veitch’s departure. Much of the rest feels like little more than raiding “Notes Towards a Vegetable Theology” for concepts without developing them further. A few guesses can be hazarded—it’s easy enough to see how the warning of the corrupting influence of the Forest Lords [who Gaiman speculates in “Notes Towards a Vegetable Theology” once led an attack on humanity that was repelled by a previous Erl-King, and who he suggests might have prompted Woodrue’s actions at the start of Moore’s Swamp Thing run] could turn Woodrue into the big villain suggested in the 1989 interview. And it’s an easy enough leap from the Forest Lords to the “Wolves of the Forest.” But all of this is speculation.

In any case, very little of this was actually picked up on in practice. Doug Wheeler, the scab who ultimately succeeded Veitch, picked up on the mention of Matango, who had previously been teased at the end of the Steve Bissette-penned Swamp Thing Annual #4, which otherwise offered a retelling of Moore’s Superman/Swamp Thing story “The Jungle Line” with Batman and a version of the cordyceps fungus in place of the Kryptonian Bloodmorel. Wheeler developed him into an elemental that was long ago corrupted by the fungal powers of the Grey. This plot made fleeting use of the phrase “forest lords” as well, but imagined them as an interplanetary entity that “seeded the planets with the potential for life,” and was very bad. Certainly it was not what Gaiman intended, save perhaps for the plot point of Matango being associated with fungus, that having been at least broadly set up in Swamp Thing Annual #4, although Bissette left room for him to be any sort of elemental of decay. Past that, however, nothing is known, and the idea of Neil Gaiman’s Swamp Thing must remain merely speculative.)

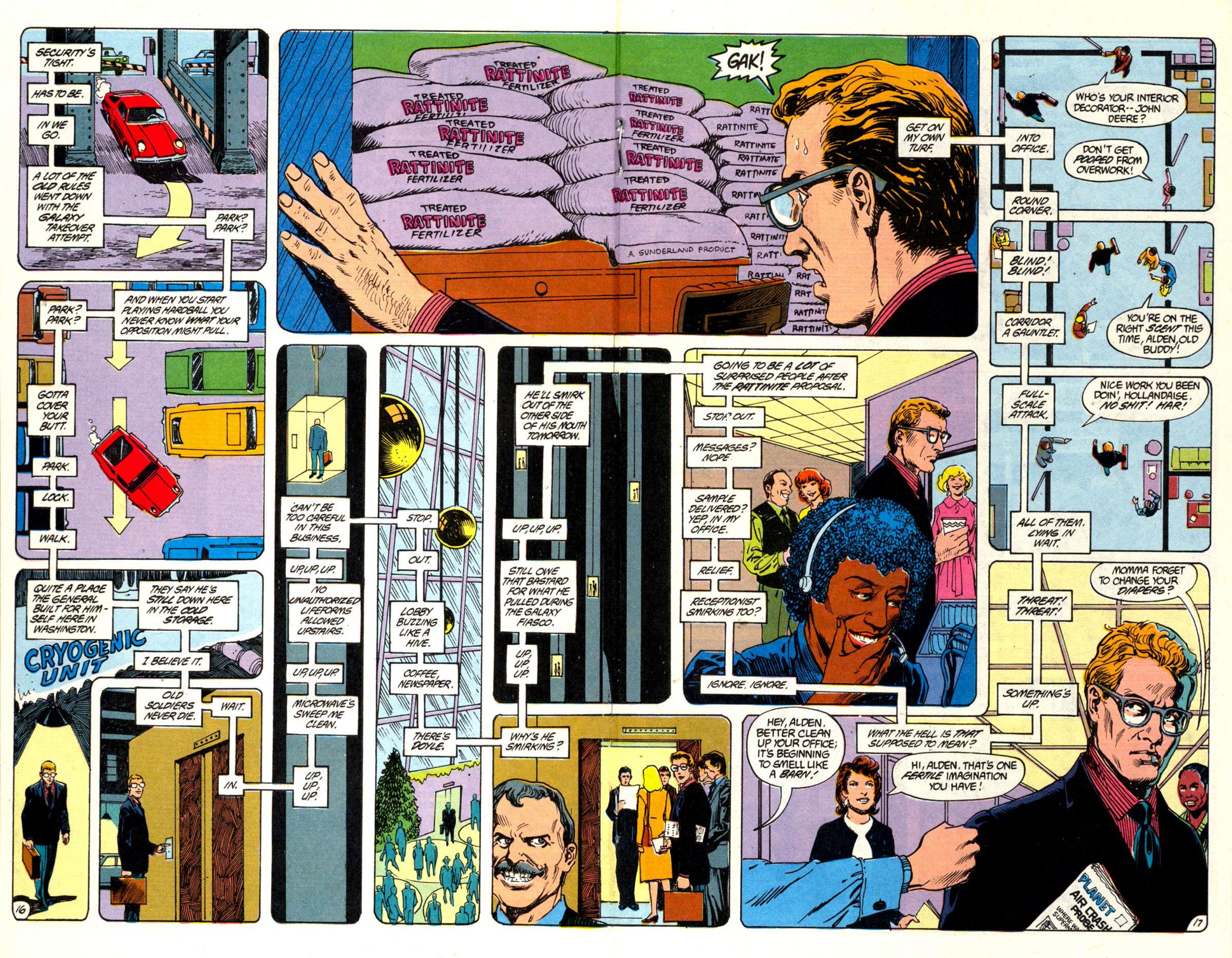

Subsequent issues start to run the concept into the ground a bit—the next issue features Gary Holland, a superstitious businessman with a sense that he’s about to die in a plane crash, which a returning John Constantine attempts to ensure in order to get the sprout properly birthed and resolve the mounting spiritual crisis only to have Swamp Thing unwittingly pull the rug out from under him by helping dispatch the souls to heaven. After that comes one of Veitch’s more effective issues, titled “Gargles in the Rat Race Choir,” and built out of twisting double page spreads with idiosyncratic reading orders traced by a series of tensely paranoid narration captions from Alden Hollandaise, an office drone at the Sunderland Corporation responsible for a scheme involving repurposing nuclear waste into fertilizer. This time it’s John Constantine that nixes things, deciding that he’s unwilling to let this guy become the next elemental and preventing Swamp Thing from guiding the sprout into him. It’s an effective enough issue with some solid formalist bona fides, even if the riffs on Alec Holland’s name start to feel ridiculous.

(Following Grant Morrison’s two issue stint, Berger opted to give her other hot new prospect a run-out on Hellblazer. Coming out midway through the A Doll’s House arc of Sandman, Neil Gaiman’s “Hold Me” is an efficient demonstration of exactly why he was such a hot prospect. A ghost story in twenty-four pages, it is a moving and inventive triumph of a one-shot that feels instantly like a perfect embodiment of everyone’s instinctive idea of what Hellblazer should be.

(Following Grant Morrison’s two issue stint, Berger opted to give her other hot new prospect a run-out on Hellblazer. Coming out midway through the A Doll’s House arc of Sandman, Neil Gaiman’s “Hold Me” is an efficient demonstration of exactly why he was such a hot prospect. A ghost story in twenty-four pages, it is a moving and inventive triumph of a one-shot that feels instantly like a perfect embodiment of everyone’s instinctive idea of what Hellblazer should be.

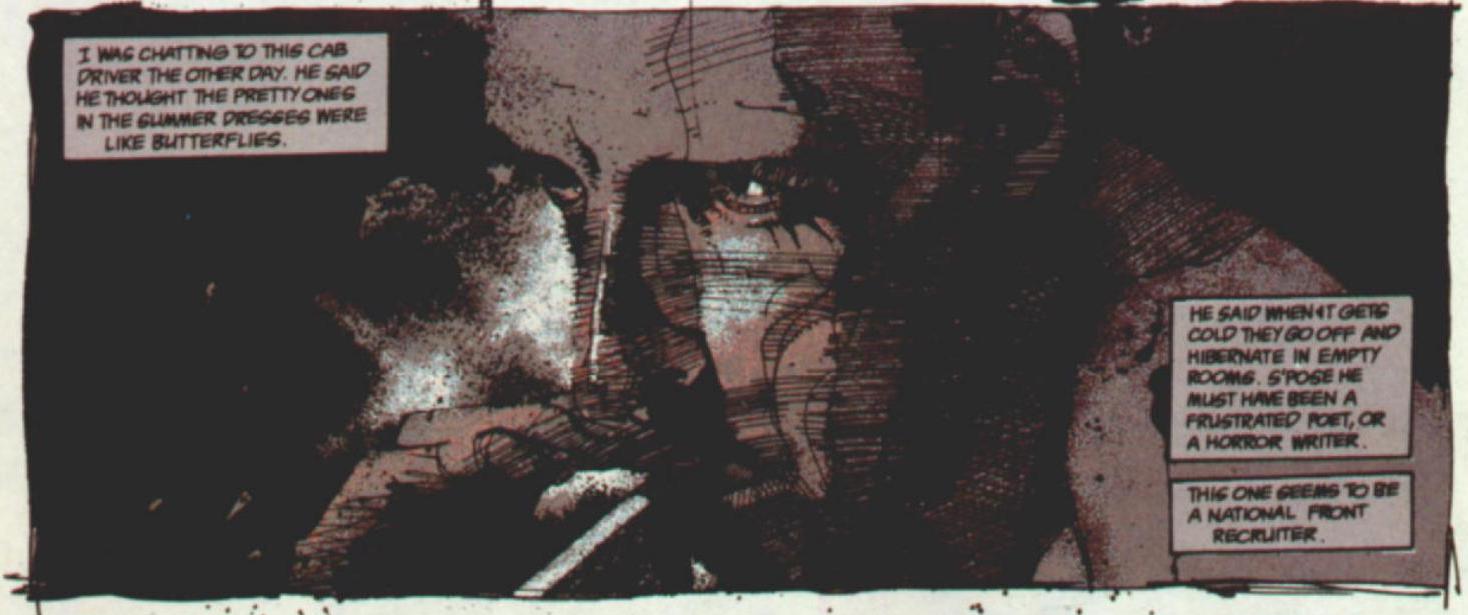

On the one hand, like Morrison’s two issues, it fits smoothly into the tone of Jamie Delano’s larger run. For one thing, it features art from Dave McKean, who did the covers of the first twenty-one issues of Hellblazer, and whose vivid but abstract depictions of their contents were an essential part of the darkly striking aesthetic of those comics. His interior art is clearer and more representational. Like David Lloyd’s art in the two issues previous, it consists of little more than a jet black line and an ink wash. But where Lloyd’s art is open and suffused with a rainbow of pastels, McKean’s panels are vast shadows pooling around small caches of light in which the scratchy characters huddle. The color palette, applied by Daniel Vozzo after McKean flew to the US to show precisely what he wanted, is muted in the extreme—washes of greying blues and purples with only a few scratches of red for subtle yet effective emphasis. The similarities to the dark, dense hatching of those early John Ridgway issues is pronounced, but McKean pushes the style even further into a sort of comic book expressionism, distorted and ominous.

Gaiman also takes care to ground his story in the plot of Delano’s run. The inciting incident for the plot is Constantine attending a memorial for Ray Monde, the gay friend of his who died protecting Zed from the Resurrection Crusade back in Hellblazer #7. More to the point, however, Gaiman adopts the politics and attitude of Delano’s work. Gaiman is in no way a writer who shies away from politics [it’s difficult to become a majro combatant in a magical war for the soul of Albion while shying away from politics] , but he is rarely as prone to the bluntness involved in having John Constantine storm out of a taxi after the driver goes on about how “old Enoch, he had the right idea. Should have sent them all back to Bongo-Bongo land” and then, when the driver asks for a tip, tell him to “get a new mind. The one you’ve got now is narrow and full of crap.” Indeed, Gaiman is arguably going a bit too far here, turing Constantine into an tweely liberal quip machine out of an Aaron Sorkin teleplay instead of someone with a sense of compassion who is at home in the foresaken margins of society and so is adept at serving as the reader’s guide within them.

Elsewhere in the issue, however, Gaiman does far better. He builds up to the actual conflict by having Constantine run into a homeless man outside the pub where the memorial is being held, talking to him about how he hates the cold once the autumn settles in and about how he got beat up by a couple drunk yuppies the other night. “Seems like there didn’t used to be so many homeless on the streets,” Constantine muses. “I gave him a quid and some cigarettes, and he seemed pathetically grateful.” And indeed, the story as a whole is built out of Gaiman’s own experience visiting a friend, noticing a bad smell coming from a neighboring apartment, and hearing the story of a homeless man who had broken into it in the winter and died, undiscovered until the spring.

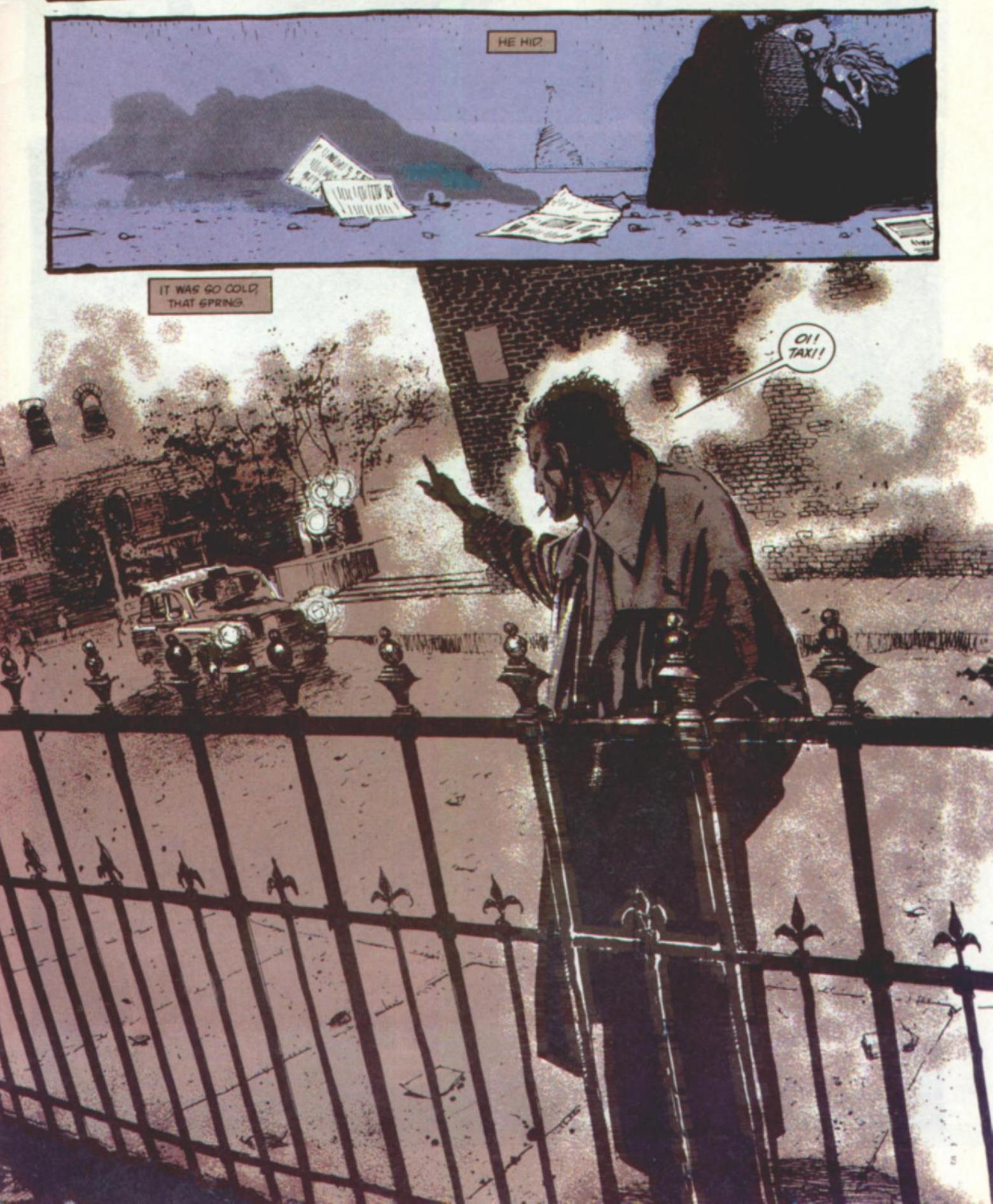

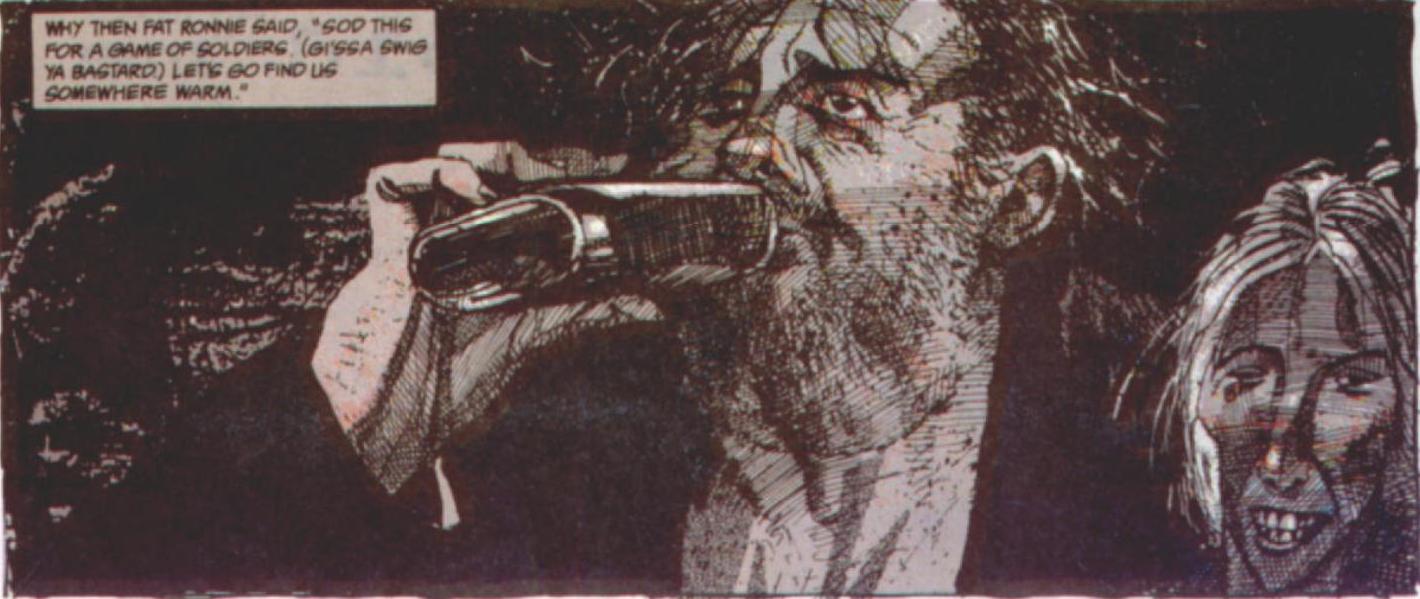

But while Gaiman is consciously playing within Delano’s style and iconography, Gaiman displays none of the awkwardness in storytelling that characterize Delano’s run. “Hold Me” is carefully structured, introducing the story of Fat Ronnie, Sylvia from Hull, and Jacko in its first four pages, then spending the next four establishing both Constantine’s situation for the issue [attending the memorial for Ray Monde and meeting Anthea there] and sketching out theme with the encounter with the homeless man, and even a quick bit of caption boxes in which Constantine recalls another cab driver telling him about how he thinks the pretty girls one sees in summer “go off and hibernate in empty rooms” come the winter, a deft repetition of the story’s central motif. Gaiman then cuts to a two-page section of the zombie Jacko killing a young girl’s mother when she goes to investigate her daughter’s claim that there’s “a smelly man in my bedroom.” And from there the issue is a fourteen page straight shot of horror as Constantine goes home with Anthea, wanders lost in her tower estate, encounters the young girl trying to find help for her mother, and finally finds and confronts Jacko. It’s efficient, clear storytelling—doubly important given that McKean’s broad and abstract style, for all that it’s visually impressive and moody, is considerably less transparent in its storytelling than, to take someone at the opposite end of the spectrum, the crisp clarity of Dave Gibbons. Instead of forcing McKean out of his moody purples to communicate the time jump between Jacko’s death in the cold spring and the autumn setting of the main story or relying on anything so bland as a caption reading “six months later,” Gaiman has the last line of the opening narration, “it was so cold that spring,” sit over a large panel of Constantine hailing a taxi to blend the translation, with the time shift being communicated by Constantine’s description of “when the leaves start to crisp and yellow, and the mists crawl in off the Thames.”

This also highlights how Gaiman works the language of the story in a way that is not only obviously indebted to Moore but that comes off well in the comparison. The narration is more prosaic than Moore is prone towards—it opens, “It was Fat Ronnie’s idea. It was so cold that spring. Fat Ronnie and Sylvia From Hull used to hang around together and somewhere along the way Jacko wound up wandering with them. So when the old bill came round with their bloody hoses at three in the morning, when they’d just got settled under the bridge… why then Fat Ronnie said, ‘sod this for a game of soldiers. [Gi’ssa swig ya bastard.] Let’s go find us somewhere warm.” But instead of falling into the iambic rhythm of Moore, Gaiman adopts a more conversational patter—note the deft detail of Fat Ronnie demanding a swig of Jacko’s bottle in the middle of corralling everyone towards warmth, emphasized by McKean’s illustration of Fat Ronnie taking a drink—but is no less effective for it. And he doesn’t shy away from interspersing poetry within it—later he writes, “ there was no one to hold Jacko anyway. Ice-crystals glittered on the window glass, and the lights of London burned clear and cold in the darkness. He had to get away,” letting the transition from Jacko’s loneliness to his decision to flee be made entirely with evocative imagery of a desolate and cold-haunted city. And, of course, there’s the repeated line “it was so cold that spring,” which does fall into Moore’s iambs [even in its variation on the title page, “it was so very cold that spring”].

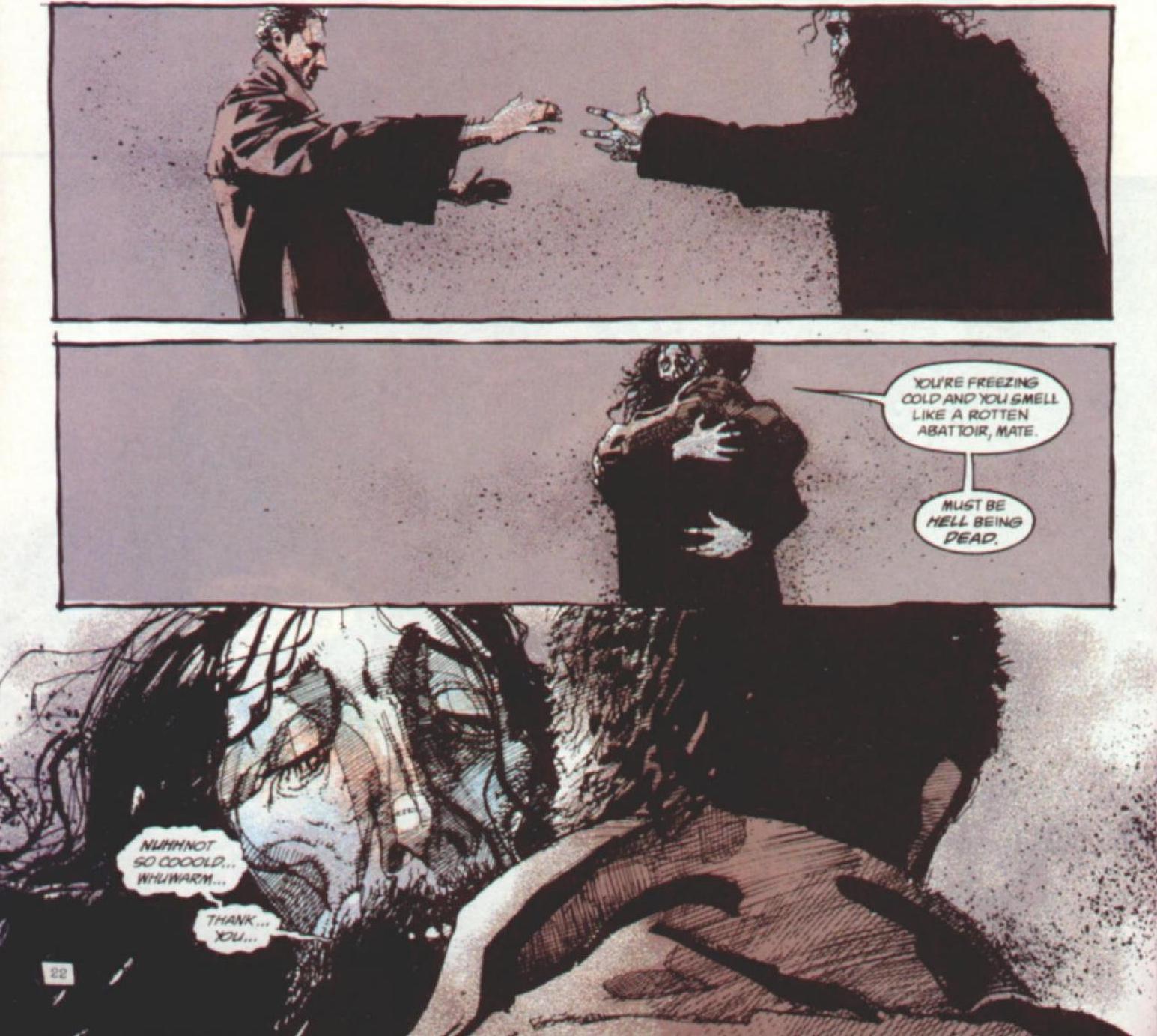

The real heart of why “Hold Me” stands out, however, is Gaiman’s skill with the emotional content of the story. The opening narration of Jacko’s last spring is an example, but the whole story is suffused with an emotional depth that stands out starkly in a run otherwise dominated by the more intellectually-focused work of Delano and Morrison [or even Moore]. The ultimate resolution comes when Constantine embraces the dead Jacko, giving him the warmth and human contact he craved [while, in a very John Constantine beat, telling him “you’re freezing cold and you smell like a rotten abattoir, mate. Must be hell being dead”]. The final image is Constantine going back to Anthea’s flat and asking her to hold him, an ending that puts the focus firmly on the emotional catharsis. Even a comparatively minor like Constantine realizing that the girl who’s invited him home is a lesbian who’s just trying to seduce him to get pregnant is well-handled, with the story taking a moment to linger on his wounded pride, sulking “you could have bloody asked, you know. That’s all. You could have bloody asked.” [And Gaiman wisely grounds the reaction in Constantine’s previous experiences with the idea.] At the end of the day, “Hold Me” is a story about homelessness and poverty under Thatcher, but its angle into that is the emotional experience of loneliness and despair. Indeed, Gaiman notes that the thing that stuck out for him about his friend’s story of a homeless man dying in a nearby flat was “something about the loneliness that must have been involved, about why no one cares.” For Gaiman, the emotional experience of homelessness and that people have about homelessness are where any engagement with the concept starts.

It is no great revelation that, while all of the major combatants in the War are tremendously successful writers, Gaiman enjoys a level of popular and commercial success an order of magnitude higher than the others. And while “Hold Me” shows Gaiman on particularly high form [he notes that “‘Hold Me’ is one of the comics of which I am most proud. I feel like I did something good there], it’s also a comic that one can look at and immediately see why its author went on to have the reputation that he did. It is a mixture of skillfully executed and rawly enjoyable that few writers can reproduce, and fewer still with any reliability. More even than the unquestionably brilliant but also dense and weighty Watchmen, “Hold Me” is a comic that one can present to someone and have them immediately see its virtues. Its mix of well-sketched spookiness and larger than life emotional vividness is self-evidently potent—a winning formula that would go on to win very big indeed.)

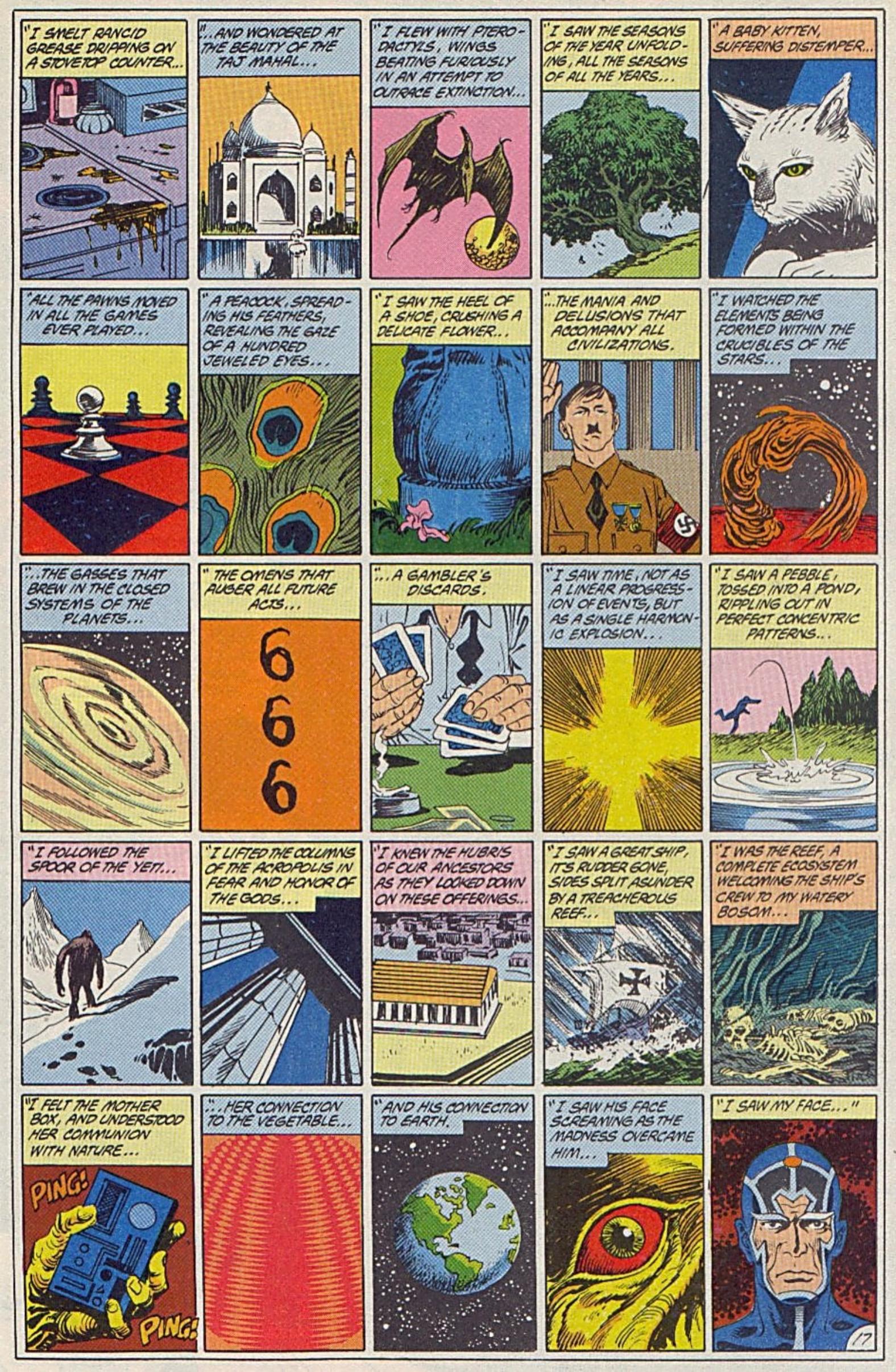

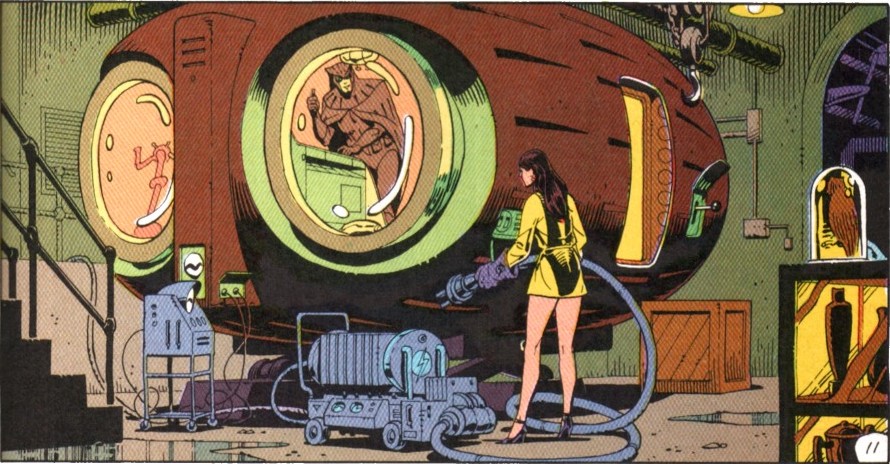

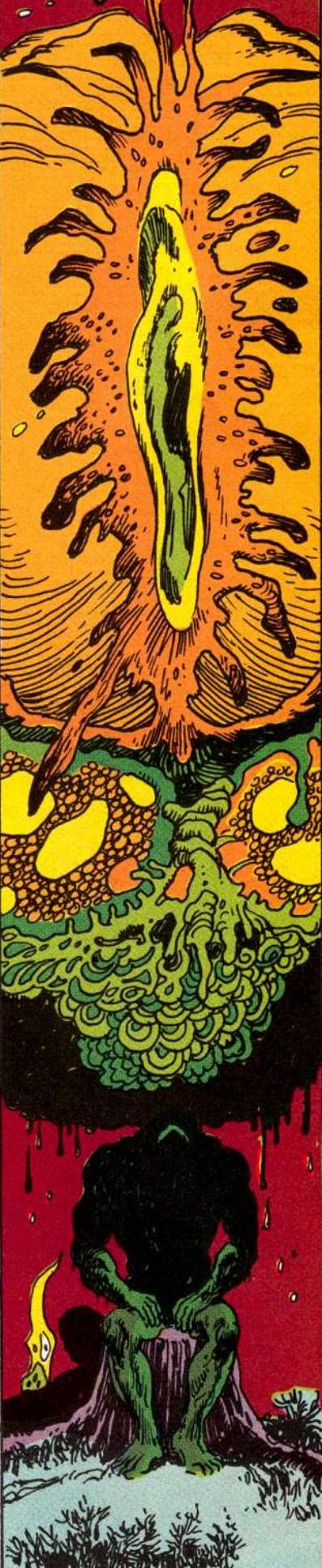

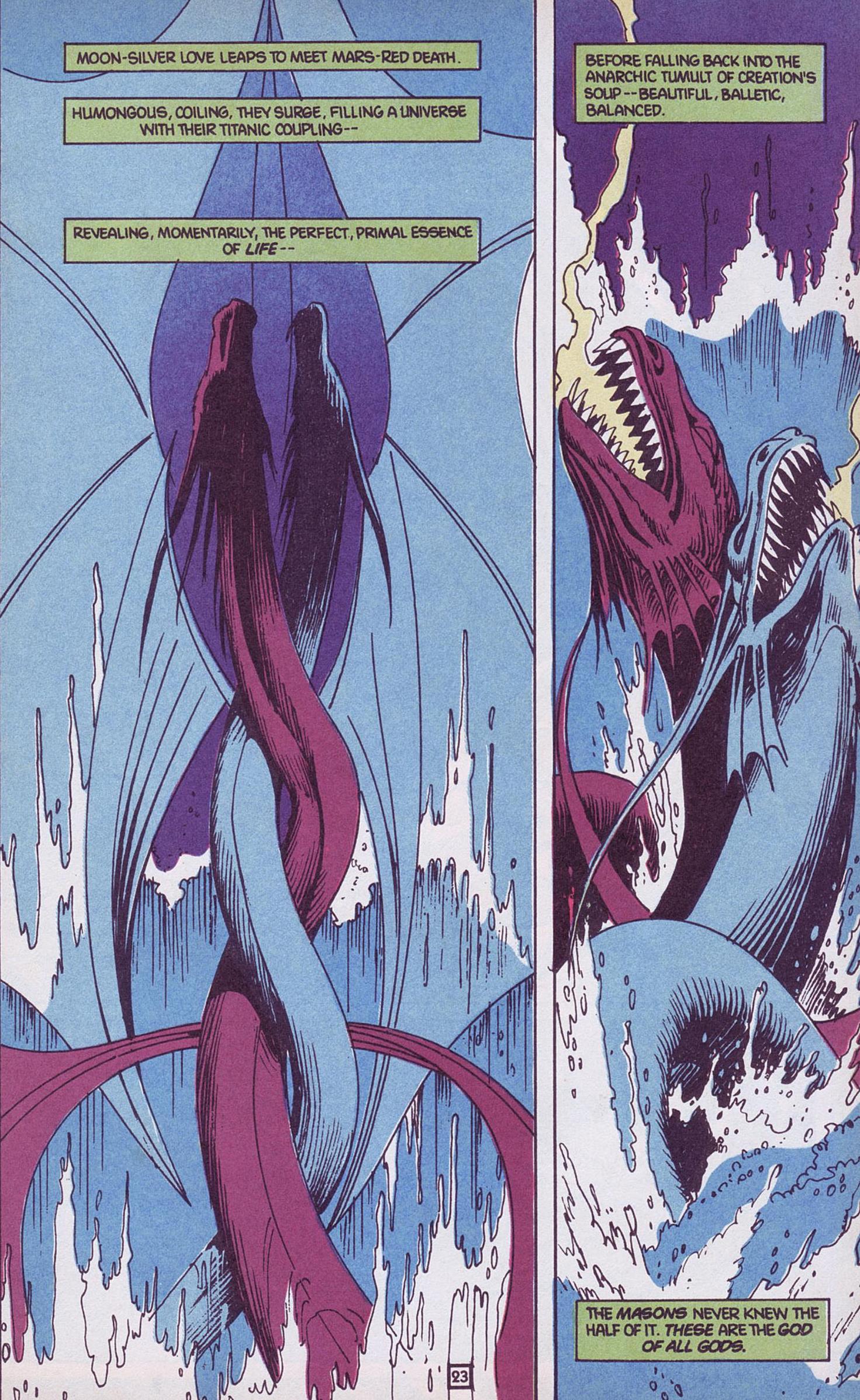

The issues after, however, which feature both Chester and Abby nearly becoming the next Swamp Thing, really start to cross into beating a dead horse similarly to the repetitive monster stories of the American Gothic arc did for Moore, only largely worse because the endless incarnations of the Sprout give even less room for play, and feel more farcical in their failure to resolve. Thankfully, Veitch pulls out of the downturn with Swamp Thing #75, “The Thinker.” In it, Swamp Thing attempts to come up with a way out of the sprout dilemma that does not involve euthanizing the sprout’s soul. On Abby’s suggestion, he grows himself a biocomputer to augment his thinking capabilities and begins to ponder. This is the impetus for Veitch to do one of the psychedelic essays he and Moore enjoy so much, as Swamp Thing ponders the nature of humanity, evolution, and history searching for a way forward. It is nothing the book has not done before—indeed nothing Veitch hasn’t done before, and “The Thinker” is not even a particularly stand-out iteration of it, but it comes satisfyingly close to a Swamp Thing idea that always works. And by the end of the issue Swamp Thing has an idea, and the story can finally move forwards.

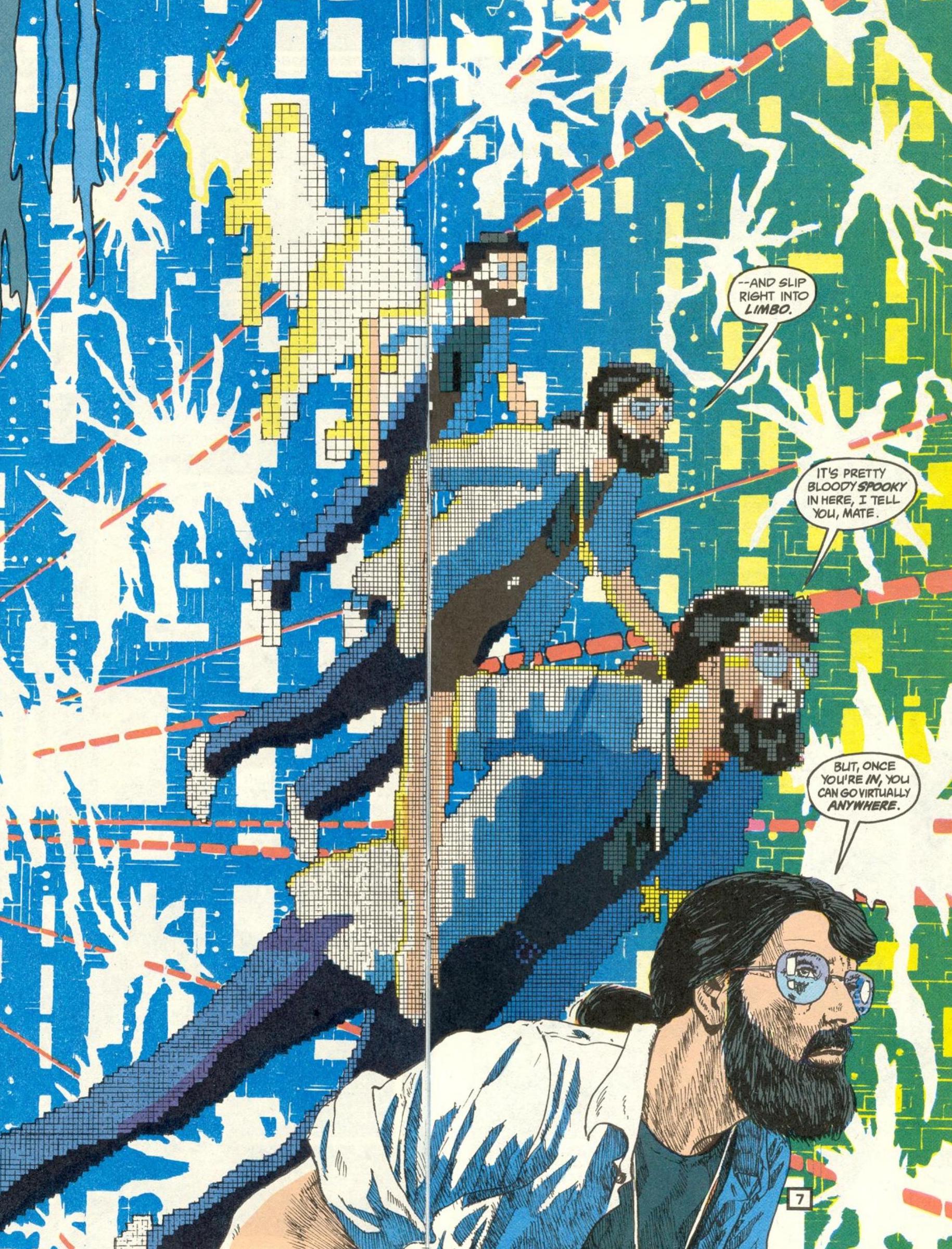

Meanwhile, in Hellblazer, Delano was in the midst of an increasingly muddy plot involving the competing machinations of a Christian fundamentalist sect called the Resurrection Crusade and a bunch of demon worshippers called the Damnation Army and led by the menacing Nergal, a demon who has some as of yet unknown history with Constantine. Delano is almost always at his worst when trying to structure a big multi-issue plot, but as usual individual moments still crackle, most obviously a cyberpunk-inflected sequence in which another one of his old friends from the mysterious Newcastle incident helps him hack the Resurrection Crusade before making a wrong step as he encounters some unexplained, paradise-like universe within the computer system that leads his body to incinerate in fromt of Constantine. This, combined with the death of his friend Ray Monde, who is beaten to death for being gay by the Resurrection Crusade whilst they kidnap Zed, a girl he was protecting on John’s behalf, drives Constantine over the edge into another depressive spiral.

It is here that Swamp Thing’s plan begins to intersect it’s sister title. The plan, as come to in “The Thinker,” is that Swamp Thing and Abby need to have a child themselves into which the sprout can incarnate. This is, apparently, because of the magical properties of the human womb, “where all memories of suffering and triumph are erased, and the slate of each soul wiped clean in preparation for its next voyage back into the realms of earthly illusion.” From this, Swamp Thing concludes that the sprout could be purified if it gestated inside a human womb, imagining that the future elementals will be “dressed not in foliage, but in flesh.” This is hazily explained at best, but the fact that it comes at the climax of a psychedelic vision sequence helps paper over the gaps.

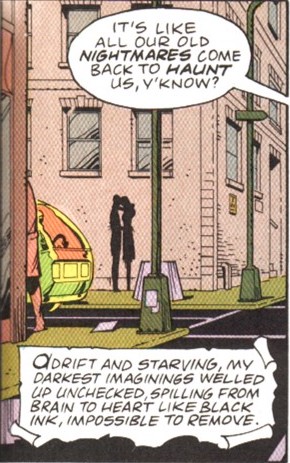

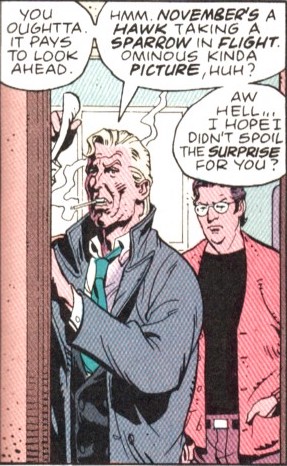

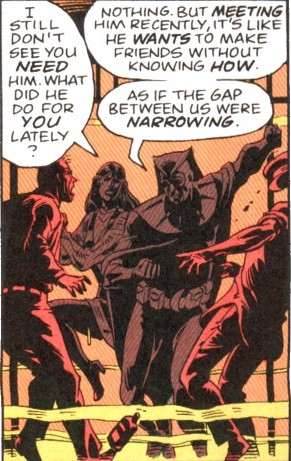

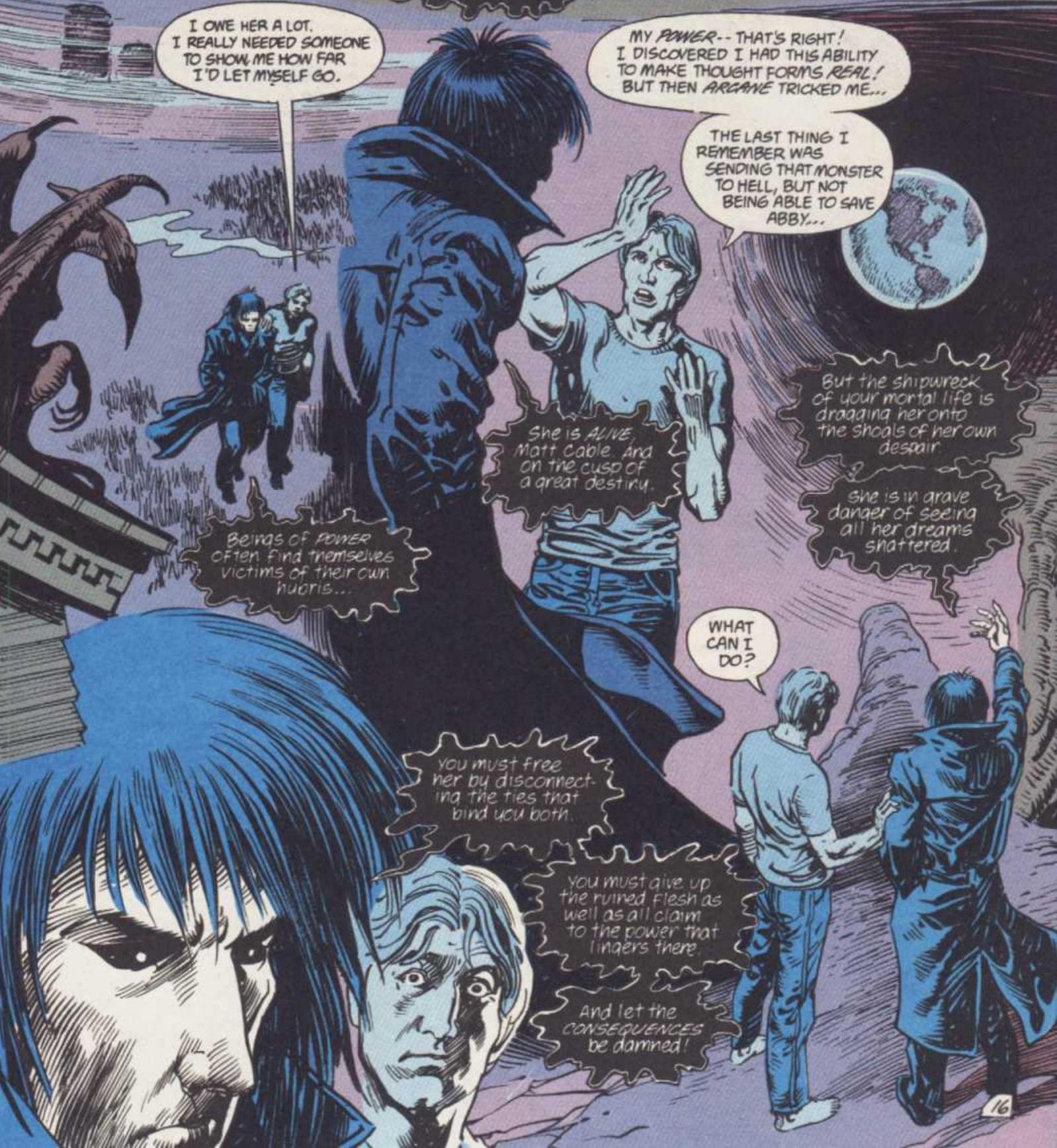

“The Thinker” ends with a note that it will be continued in Hellblazer #9, an issue that sees Constantine at rock bottom, imagining the ghosts of all the people he’s let down and caused the death of, drinking himself into a stupor, and fleeing a figure that animates itself out of various objects—rags, newspapers, and eventually money. To a remotely savvy reader (especially one who knows this is continuing off of “The Thinker”) this is obviously Swamp Thing, but it is not until Constantine pulls himself together and decides to get back to the manipulative game-playing that he’s good at that this thread is allowed to resolve. After a quick bit of sabotage of the Resurrection Crusade’s plans to create a new messiah by nipping off and having a covert tryst with the aforementioned girl, thus contaminating her with the demon blood that had been infused into him by Nergal, he returns to his apartment with one last item on his agenda: a prophecy relayed by Nergal of a child conceived on the winter solstice of “a conjunction between nature and super-nature.” And so as Swamp Thing manifests himself out of Constantine’s cigarettes, Constantine explains his plan.

“The Thinker” ends with a note that it will be continued in Hellblazer #9, an issue that sees Constantine at rock bottom, imagining the ghosts of all the people he’s let down and caused the death of, drinking himself into a stupor, and fleeing a figure that animates itself out of various objects—rags, newspapers, and eventually money. To a remotely savvy reader (especially one who knows this is continuing off of “The Thinker”) this is obviously Swamp Thing, but it is not until Constantine pulls himself together and decides to get back to the manipulative game-playing that he’s good at that this thread is allowed to resolve. After a quick bit of sabotage of the Resurrection Crusade’s plans to create a new messiah by nipping off and having a covert tryst with the aforementioned girl, thus contaminating her with the demon blood that had been infused into him by Nergal, he returns to his apartment with one last item on his agenda: a prophecy relayed by Nergal of a child conceived on the winter solstice of “a conjunction between nature and super-nature.” And so as Swamp Thing manifests himself out of Constantine’s cigarettes, Constantine explains his plan.

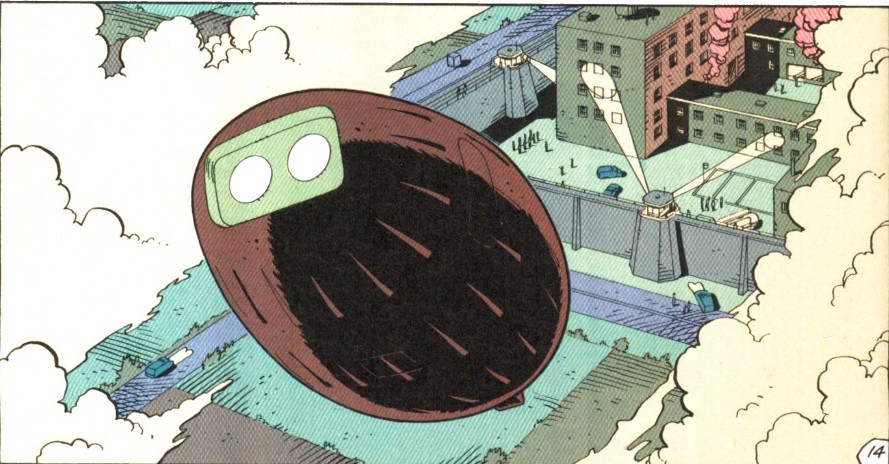

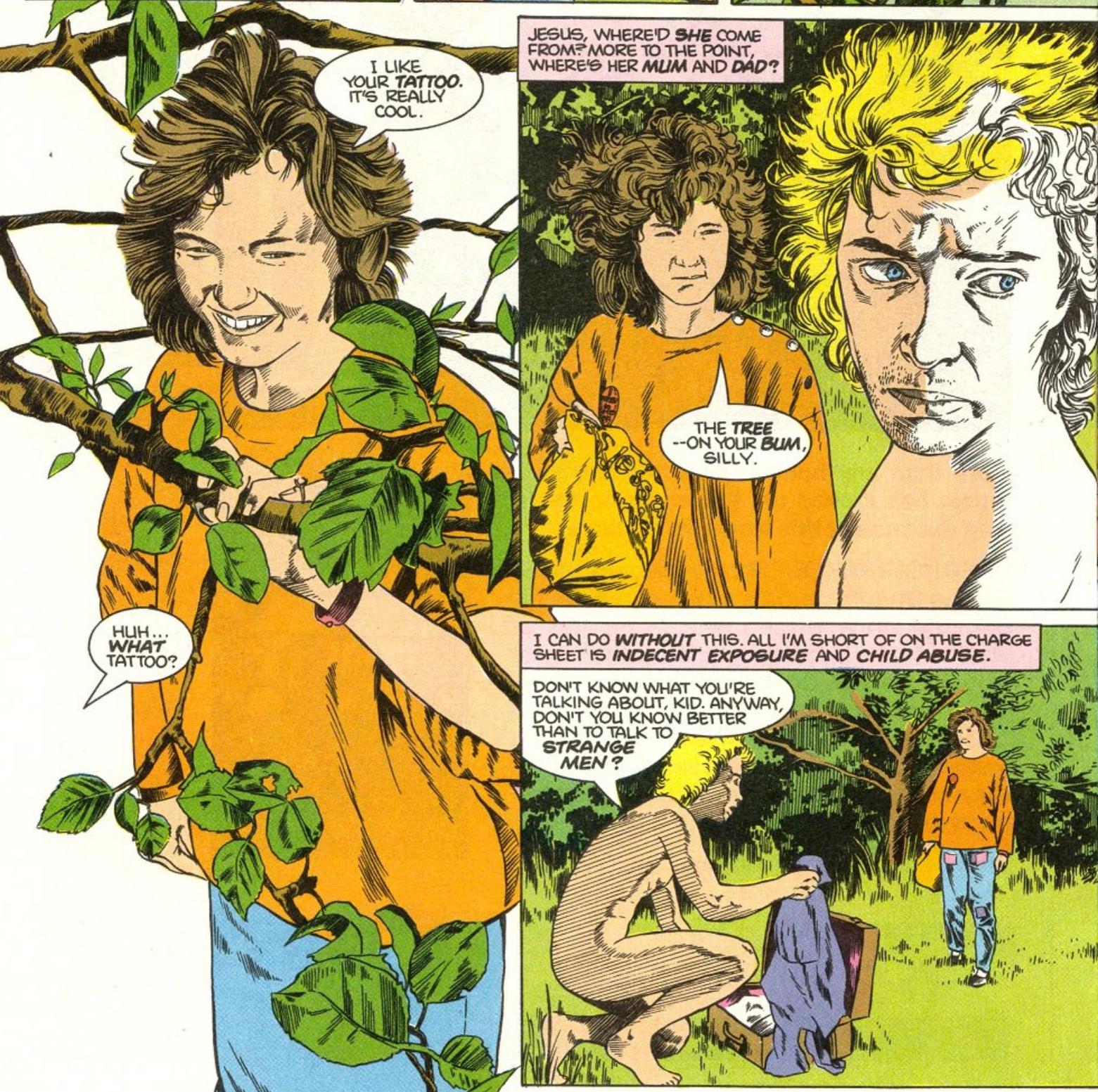

This plan, as it happens, is the same as Swamp Thing’s. And so in Swamp Thing #76, Swamp Thing possesses John Constantine’s body and heads back to Louisiana. The resulting issue is an oddly structured thing the parts of which largely exceed the whole, if only because there are so many of them. In one strand, Abby mills about, processing her emotions at the idea of having Swamp Thing’s child. This involves both touching scenes, such as her visiting her comatose husband Matt in the hospital and taking it as a sign when his wedding ring falls off his finger, to deeply humorous ones, such as when she stops by to visit Chester only to discover that he’s naked save for a pair of socks and sheepishly explaining that he and Liz Tremayne have “reached a critical point in our relationship!” Elsewhere, Veitch checks in on Anton Arcane in hell and chronicles the encounters Swamp Thing-in-Constantine has on his trip, including an astonishing throwaway scene in which he encounters Jack Kirby’s bitter Stan Lee parody Funky Flashman at the airport and is subjected to a lengthy pitch about how they should plot out a Swamp Thing/Darkseid fight for the profit of both Flashman and Constantine. But perhaps the issue’s most delightfully random beat sees Swamp Thing take John Constantine’s body by a tattoo parlor to get him an unwanted tattoo as revenge for all the trouble Constantine has gotten him into.

This plan, as it happens, is the same as Swamp Thing’s. And so in Swamp Thing #76, Swamp Thing possesses John Constantine’s body and heads back to Louisiana. The resulting issue is an oddly structured thing the parts of which largely exceed the whole, if only because there are so many of them. In one strand, Abby mills about, processing her emotions at the idea of having Swamp Thing’s child. This involves both touching scenes, such as her visiting her comatose husband Matt in the hospital and taking it as a sign when his wedding ring falls off his finger, to deeply humorous ones, such as when she stops by to visit Chester only to discover that he’s naked save for a pair of socks and sheepishly explaining that he and Liz Tremayne have “reached a critical point in our relationship!” Elsewhere, Veitch checks in on Anton Arcane in hell and chronicles the encounters Swamp Thing-in-Constantine has on his trip, including an astonishing throwaway scene in which he encounters Jack Kirby’s bitter Stan Lee parody Funky Flashman at the airport and is subjected to a lengthy pitch about how they should plot out a Swamp Thing/Darkseid fight for the profit of both Flashman and Constantine. But perhaps the issue’s most delightfully random beat sees Swamp Thing take John Constantine’s body by a tattoo parlor to get him an unwanted tattoo as revenge for all the trouble Constantine has gotten him into.

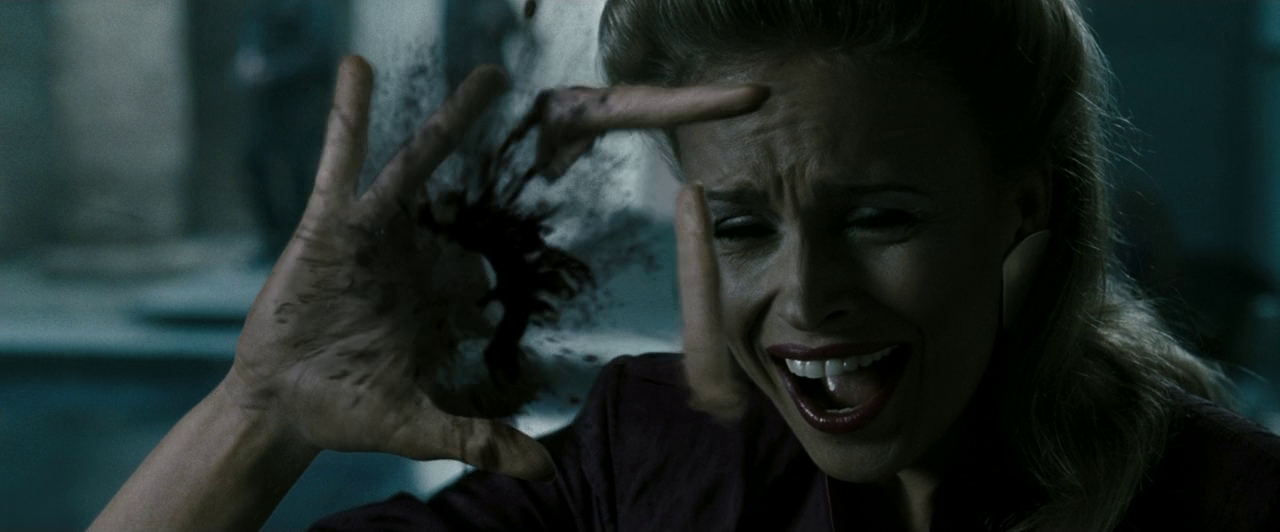

Eventually, however, the issue gets down to the actual plan, in which Swamp Thing has sex with Abby while in Constantine’s body, thus allowing for the creation of a new elemental. (This will eventually be Tefé Holland, who will go on to a lengthy tenure as a minor supporting character that nobody quite knows what to do with, the highlight of her existence being a short-lived Swamp Thing series in the 2000s written by an emerging Brian K. Vaughan.) It is a deeply strange and bewildering plot point that can easily be argued as ill-chosen, though Veitch and Delano do manage to avoid the worst possibilities by making sure everyone involved is aware of and consenting to the plan. Still, it’s an unsettling plot point, and it’s not a surprise that the two issues of Swamp Thing following are dedicated to sorting it out. The first, a guest issue by Delano, is largely successful—Abby decides she needs some time alone following waking up next to Constantine back in his own body and storms off to be alone, only to encounter Constantine again and reconcile with him over a night of drinking before he chivalrously avoids sleeping with her again, instead getting up before her, buying her breakfast, and getting her back to Houma to reconcile with Swamp Thing. The second, penned by Steve Bissette, sees Swamp Thing accidentally take on female form and then give birth to another body which rapidly grows back to his normal form; the less said about this the better.

Eventually, however, the issue gets down to the actual plan, in which Swamp Thing has sex with Abby while in Constantine’s body, thus allowing for the creation of a new elemental. (This will eventually be Tefé Holland, who will go on to a lengthy tenure as a minor supporting character that nobody quite knows what to do with, the highlight of her existence being a short-lived Swamp Thing series in the 2000s written by an emerging Brian K. Vaughan.) It is a deeply strange and bewildering plot point that can easily be argued as ill-chosen, though Veitch and Delano do manage to avoid the worst possibilities by making sure everyone involved is aware of and consenting to the plan. Still, it’s an unsettling plot point, and it’s not a surprise that the two issues of Swamp Thing following are dedicated to sorting it out. The first, a guest issue by Delano, is largely successful—Abby decides she needs some time alone following waking up next to Constantine back in his own body and storms off to be alone, only to encounter Constantine again and reconcile with him over a night of drinking before he chivalrously avoids sleeping with her again, instead getting up before her, buying her breakfast, and getting her back to Houma to reconcile with Swamp Thing. The second, penned by Steve Bissette, sees Swamp Thing accidentally take on female form and then give birth to another body which rapidly grows back to his normal form; the less said about this the better.

Delano’s Hellblazer run continued for nearly three years after its crossover with Veitch’s run. In the immediate term, this involved picking up on the Nergal thread by having Constantine finally realize that his past connection with Nergal relates to the mysterious Newcastle incident. This leads into Hellblazer #11, which finally flashes back to tell that story. The result is a mixed bag—the issue is an effective piece of horror that makes good use of the idea of a young John Constantine who is in way over his head. And yet the actual plot—Constantine botches a demonic summoning, resulting in the death of a young girl—cannot help but be a disappointing answer to the long-seeded mystery of what awful thing happened in Newcastle that had been woven into Constantine’s backstory from the start. In much the same way that the demonic soul brokers story in Hellblazer #3 shows the ways in which Delano’s approach can work in spite of its limitations, the Newcastle revelation shows the level it can never quite surpass—the way in which it cannot ever quite nail a big moment.

With the dark history of Newcastle revealed, Delano wraps up the Nergal storyline with another cyberpunk issue before doing a one-off with a nuclear paranoia dream sequence. This transitions into Delano’s second major arc, The Fear Machine, which at nine issues is the longest single story of his run. (The first trade paperback is also nine issues long, but collects the two issue Mnemoth story, the demon investment one-off, and, bafflingly, the first six issues of the Resurrection Crusade/Nergal story, which can be argued to also be nine issues long, but is better understood as two stories that dovetail each other in the manner that comics syndication often does.)