The Dead Marshes (II: Gollum)

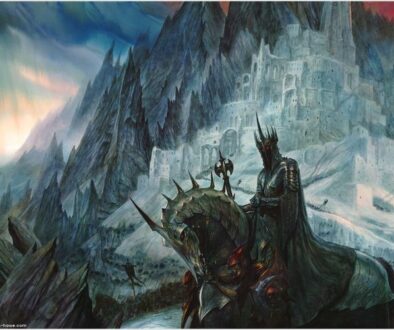

A portrait of Gollum follows.

The Dead Marshes serve as much as an introduction to the nature of Gollum as they do to the geographic and ontological contours of Mordor and its surrounding lands. In many ways, Gollum embodies the zeitgeist of Middle-earth more completely than any other character in The Lord of the Rings. Gollum is a pauper of paradox; he’s one of the trilogy’s few truly autonomous characters, having few loyalties (and no consistent ones) and little deference to the passing of time, and yet he is powerless. Throughout The Lord of the Rings Gollum is a pawn for both the Free Peoples of Middle-earth and Mordor’s forces. His demise is inadvertently caused by the decisions of both factions, and he experiences degrading and at times sadistic treatment from all of his captors. Gollum’s relationship with free will is inconsistent, evincing the paradox of Tolkien’s fervent Catholicism and racial-cultural essentialism. In short, he’s Tolkien’s entire creation in one character, embodying The Lord of the Rings’s ethos each time he materializes.

When he first appears in The Hobbit, Gollum is the fairy tale monster that other fairy tale monsters fear. Living under the Misty Mountains, Gollum, “a small slimy creature,” rules the literal underworld from his perch by an underground lake, aided by his magic ring. An unknowable yet strangely charismatic horror, he is described with something nearing reverence:

Deep down here by the dark water lived old Gollum, a small slimy creature. I don’t know where he came from, nor who or what he was. He was Gollum—as dark as darkness, except for two big round pale eyes in his thin face.

The Hobbit, Chapter V, “Riddles in the Dark”

A creature of ravenous hunger (and atypically for a menacing fantasy creature, very small), Gollum’s rule under the Misty Mountain is pervaded by his appetites. Living in his lake, he “paddle[s]” around searching for “blind fish” to eat, sometimes capturing the odd helpless goblin who ventures into his domain, “throttl[ing] them from behind,” with “his long fingers” whenever they come down. Based on the evidence, Gollum appears to live quite a satisfying life by the time of The Hobbit. He gets to eat as many goblins as he likes, and the threat of disappearance keeps the goblins from coming down to figure out who ate their comrades last watch. There’s a strange English middle class quality to this; Gollum is a Weird corruption of an English gentleman, keeping to himself and owning his hole in the ground like a respectable halfling would.

Certain staples of Gollum are already in place in “Riddles in the Dark,” the classic chapter Gollum first appears in. His ravenous hunger and avarice are fully formed in The Hobbit, while backed by a confidence Gollum has long since lost by The Lord of the Rings. Gollum’s tendency of addressing himself as “precious” is already there, although referring to the Ring that way is not yet in place (he instead calls it “my birthday present”). Gollum swerves between referring to Bilbo as “he” and “it,” suggesting a fluidity in his use of language. Gollum has enough semblance of his old near-hobbitish self, that he has pockets in which he stores “fish-bones, goblins’ teeth, wet shells, a bit of bat-wing, a sharp stone to sharpen his fangs on, and other nasty things.” There’s even some biographical detail indicating Gollum’s past associations with civilization, when Gollum remembers a day “ages and ages before when he lived with his grandmother in a hole in a bank by a river.”

Some characteristics change in Tolkien’s revision of The Hobbit in preparation for The Lord of the Rings. The original ending of “Riddles in the Dark,” where Gollum surrenders the Ring to Bilbo, is replaced by an “authentic” ending where a ring-crazed Gollum tries to murder Bilbo in a fit of rage, having deduced that Bilbo stole his Ring. Gollum’s dual personality, a subtle factor in the first edition, is made explicit to mirror Gollum’s characterization in The Two Towers and The Return of the King (Tolkien provides an in-universe explanation for the discrepancies between versions in “The Shadow of the Past,” namely that Bilbo lied about Gollum gifting him the Ring).

Gollum and Bilbo’s riddle game is a sort of bonding ritual. Two halflings in fractally opposed states of existence engage in a battle of wits, one for his own survival, the other in a clever play for time. One gets the impression Gollum is desperate for conversation after centuries alone in the dark; goblins’ worst nightmares need company as well. Indeed, Gandalf speculates in The Fellowship of the Ring that when Gollum met Bilbo “there was a little corner of his mind that was still his own, and light came through it… it was actually pleasant, I think, to hear a kindly voice again.”

Peter Jackson’s adaptation of the scene in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey emphasizes this, having the Sméagol half of Gollum excitedly shout “we love games!” at Bilbo, while a consternated Gollum pushes back at him. The Jackson version in particular plays up the aspect of this being a potential friendship in another lifetime, where Sméagol might enjoy a game of riddles with Bilbo at Bag-End. So when he realizes Bilbo has stolen his “Precious,” the betrayal is all the greater. The Ring is the heart of Gollum’s existence; when it leaves him, he loses everything he lived for, his security against goblins, and the unnatural force literally keeping him alive. While Bilbo seems unaware of the sheer agony this causes Gollum (to an extent — Jackson and company play this up in the movie, giving Bilbo a selfish edge, possibly influenced by the Ring, where he figures out fairly quickly that Gollum wants the Ring), he disrupts the ecosystem of Gollum’s life to escape from the goblins and the Misty Mountains. Even in the moment where he shows mercy to the murderous Gollum, a powerful and truly Catholic moment that evinces all of Tolkien’s most redeeming aspects, the fact is that he takes away the last vestige of consistency and desire in Gollum’s life. The Ring ultimately disrupts Bilbo’s existence as well, but this act of burglary is the core moment that eventually drives The Lord of the Rings, with Gollum’s loss motivating the plot and themes of that work. And while Bilbo is ultimately able to escape the power of the Ring through his own strength of character, Gollum is forever bound up with it. From the moment he wrestles it from Deagol’s dead hands, his life is fixed around it forever, until the moment of his death.

In The Fellowship of the Ring, Gollum is offstage yet vital to the Ring quest’s impetus. We get some more detail about Gollum’s past and the Stoor people Gandalf informs Frodo of “the fathers of the fathers of the Stoors” who were “of hobbit-kind” and “loved the [Anduin] River, and often swam in it, or made little boats of reeds.” Gollum’s distant relation to hobbits, a fact only hinted at in The Hobbit, is concretely iterated, much to the horror of Frodo, who expresses his disbelief “that Gollum was connected with hobbits, however distantly.” In a surprising beat, Gandalf, Tolkien’s voice of authorial wisdom, discourages Frodo from refusing to identify with Gollum, observing that Gollum’s corruption “might have happened to others, even to some hobbits that I have known” (and indeed, it partially happens to Frodo at the end of his journey to Mordor). This sets off an arc where Frodo slowly develops a subtle kinship with Gollum, falling for some of the same traps he did, and ultimately making the near-fatal error of allowing himself to be consumed by the Ring. For once, weakness isn’t something bound to a few “races,” but is a vice all peoples are bound to, although Frodo’s virtues preserve him throughout the quest and save him in the end. Gandalf makes the observation that Bilbo and Gollum “suggests the kinship,” in that “there was a great deal in the background of their minds and memories that was very similar.”

Character-wise, descriptions of Gollum in The Lord of the Rings match and amplify his characterization in The Hobbit. When speaking of his past life as Sméagol, it becomes clear Gollum was dysfunctional and inquisitive long before the Ring came along (once again showing that the One Ring’s power over its wearer is partially determined by its wearer’s character). In his youth Gollum was “interested in roots and beginnings,” and known for digging tunnels and burrows while neglecting the sky, as “his head and his eyes were downward.” Gollum’s dark complexion is frequently highlighted; in The Two Towers, the orc Shagrat refers to him as “a little thin black fellow” (The Two Towers, “The Choices of Master Samwise”). It’s likely that Gollum’s dysfunction is rooted in inherent antisocial and anti-authoritarian tendencies; Gollum is othered again and again everywhere he goes. His family was headed by his matriarchal grandmother, “stern and wise in old lore,” mentioned in passing in The Hobbit while Gollum recalls his old babushka whom he taught to suck “eggses” (perhaps the most disturbing sentence in Tolkien’s bibliography). Gollum’s self-serving tendencies reached their apex in his wholly pointless and avaricious Cain-like murder of his friend Déagol, perhaps a hint of the Ring’s immediate power over his mind, and also a suggestion of his ingrained antisociality. The One Ring’s powers of invisibility immediately help Gollum in his connivances and schemes, but win him the scorn of his family, who gradually shun him and name him Gollum. Eventually Gollum’s grandmother, “desiring peace,” disowns him and casts him out of her family’s hole, sending Gollum into exile as he begins a life of eating raw fish (not sushi), hating the sun, rejecting social company, and mastering the COVID-19 lifestyle. When Gollum eventually finds the sun a punishment, he discovers the Misty Mountains and decides “it would be cool and shady under those mountains. The Sun could not watch me there. The roots of those mountains must be roots indeed: there must be great secrets buried there which have not been discovered since the beginning.”

Ultimately Bilbo’s theft of the One Ring motivates Gollum out of hiding. He’s a ruined figure consumed by guilt over Déagol’s murder and the corrosive effects of the One Ring, although as Gandalf puts it, he has “never faded.” Gollum’s attempts to elude his enemies is a failure, however, and reinforces the social trauma of his family’s expulsion. At various points he’s apprehended and tortured by Mordor, captured by Gandalf and Aragorn, the former of whom threatens him with torture (“I put the fear of fire on him”), and imprisoned by the Silvan Elves of Mirkwood. While Frodo wrestles with the ethics of capturing Gollum, others of his ideological persuasion seem to view their treatment of Gollum as a morally acceptable last resort, viewing humane captures and threats as noble in service of the greater good.

This all happens offstage, and Gollum spends The Fellowship of the Ring and early chapters of The Two Towers in the dark, stalking the Fellowship as they pass through Moria, Lórien, and eventually Emyn Muil. When he eventually catches up with Frodo and Sam in the latter, the drama of The Lord of the Rings changes. Until this point, Tolkien has kept his villains mostly offstage, only bringing them into scenes where the protagonists directly interact with them. Saruman and Gríma are offstage for the most of the action — Saruman only appears in three chapters in the whole of The Lord of the Rings, a decision that works on the page but inevitably had to be changed in Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, which wisely includes several appearances of Saruman and Orthanc. This absence of evil characters serves two major functions: one is that it keeps the drama centered around the heroes, a stylistic decision paralleling the mono-plot narrative structure of myths and sagas, which generally follow the adventures of one character or faction at a time. This sagaesque approach demarcates The Lord of the Rings from the often cutaway-driven narrative techniques of the modern novel, a medium Tolkien proclaimed to have “no interest at all in” (he called Rings a “heroic romance”). The other factor keeping Tolkien’s villains offstage is that he seems ambivalent towards them. The overwhelming majority of his work centers around the challenged or the falling; those who’ve fallen present no conflict for him. Their souls are lost, and Tolkien’s work lands on moral and historical complexity more often than glib “good versus evil” parables. Sauron and Saruman can’t be characters in their own right because their stories have ended, and the narrative belongs to those their tyranny now impacts. The Lord of the Rings may be the foundational novel of the fantasy genre, but the genre’s fixation on edifying villainy has little provenance in Tolkien.

When Gollum appears in The Two Towers, villainy gains a face, a personality, and an agenda. Gollum is id, avarice, fear, despair, and unbridled survival. Tolkien sometimes describes his movements as canine (“At once Gollum got up and began prancing about, like a whipped cur whose master has petted it”, “Gollum watched every morsel from hand to mouth, like an expectant dog by a diner’s chair”). He ruthlessly hates himself and lives in service of himself. In short, Gollum is an icon, a ruined wreck of neuroses and trauma. Having followed Frodo and Sam for several days, Gollum then fails to kill the hobbits, who prepare for his attack and seize him when he accosts them. For once, Gollum is in the company of people without tremendous power over him, and have some moral justification in keeping him as their prisoner due to his ‘fucking homicidal’ gig. There’s some proper moral wrestling with the treatment of Gollum throughout Book IV, at least by Frodo. Sam would rather hurl Gollum into the Cracks of Doom (the class dynamics of Frodo and Sam’s relationship ring out loudly in their views of Gollum; the rustic Sam is understandably suspicious of the malingering trickster and mistrustful of anything newfangled and odd, and cognizant of Gollum’s psychological changes — “there is a change in him” — while Frodo’s suspicion towards Gollum is balanced by enlightened, genteel compassion for his plight). And while the dynamic reveals things about Gollum’s twisted and capricious nature, it betrays some quiet nobility in him as well.

At his first meeting with Gollum, Frodo, influenced by his past conversation with Gandalf, declares “now that I see him, I do pity him.” His pity does not extend to letting Gollum free — somewhat understandably, again — and using Gollum as a guide through Emyn Muil and the Dead Marshes becomes a practical necessity. Yet Frodo takes Gollum’s redemption as something of a project. While recognizing its astronomical improbability, Frodo treats Gollum with compassion and mercy that is novel to the latter. Tolkien’s Catholic conception of grace is embodied by Frodo — he offers Gollum the kindness he sorely needs, and Gollum has the option of either accepting or rejecting it. A scene where Frodo offers Gollum lembas, the Elves’ own Eucharist, exemplifies this relationship with grace and mercy.

‘[Gollum] took a corner of the lembas and nibbled it. He spat, and a fit of coughing shook him.

The Two Towers, Book IV, Chapter II, “The Passage of the Marshes”

‘Ach! No!’ he spluttered. ‘You try to choke poor Sméagol. Dust and ashes, he can’t eat that. He must starve. But Sméagol doesn’t mind. Nice hobbits! Sméagol has promised. He will starve. He can’t eat hobbits’ food. He will starve. Poor thin Sméagol!’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Frodo; ‘but I can’t help you, I’m afraid. I think this food would do you good, if you would try. But perhaps you can’t even try, not yet anyway.’

He has not fallen as of yet — anyone still clinging to life has a choice and a path forward. Frodo gives him autonomy, letting him go off at will, being wise enough to understand that Gollum will return (“he won’t leave his Precious, anyway”). When the hobbits’ Elvish rope torments Gollum, they remove it from his ankle (although only when “At last Frodo was convinced that he was really in pain”). His case is helped greatly by the fact that the book recognizes Gollum’s pain several times over:

‘It hurts us, it hurts us,’ hissed Gollum. ‘It freezes, it bites! Elves twisted it, curse them! Nasty cruel hobbits! That’s why we tries to escape, of course it is, precious. We guessed they were cruel hobbits. They visits Elves, fierce Elves with bright eyes. Take if off us! It hurts us.’

The Two Towers, Book IV, Chapter I, “The Taming of Sméagol”

Frodo even works with Gollum to convince him they have a common cause, assuring him that helping the hobbits means the end of Sauron’s torment of Gollum. He also gives him an ultimatum, and tells him that Gollum only needs to accompany the hobbits on part of their journey, while offering him some spiritual comfort:

‘[Sauron] will not go away or sleep at your command, Sméagol,’ said Frodo. ‘But if you really wish to be free of him again, then you must help me. And that I fear means finding us a path towards him. But you need not go all the way, not beyond the gates of his land.’

Gollum sat up and looked at him under his eyelids. ‘He’s over there,’ he cackled. ‘Always there. Orcs will take you all the way. Easy to find Orcs east of the River. Don’t ask Sméagol. Poor, poor Sméagol, he went away long ago. They took his Precious, and he’s lost now.’

‘Perhaps we’ll find him again, if you come with us,’ said Frodo.

Not that Frodo doesn’t sneer at the notion of Gollum having multiple sides to his identity; he approaches Gollum on his own terms. And this does help — Gollum becomes friendly at times, endeavoring to help his guides. But he always retains an autonomous soul, interacting meticulously with his captors but switching between good will and conspiring against them, depending on whether Sméagol or Gollum has the upper hand. Sméagol is often the one with the upper hand, and the friendlier side of Gollum, but his fear and mendacity remain. The infamous scene in The Two Towers where Sam eavesdrops on Gollum and Sméagol — adapted and improved in a scene Fran Walsh wrote (and also directed for pickup shoots) in the Peter Jackson film — wholly reveals this. The now iconic dialogue, a highlight of The Lord of the Rings and one of the most relatable scenes in cinema, plays like an exorcist Sméagol attempting to banish a demonic Gollum from his own soul:

Sméagol: Go away.

Gollum: Go away?

Sméagol: I hate you. I hate you.

Gollum: Where would you be without me? Gollum. Gollum. I saved us. It was me. We survived because of me.

Sméagol: Not anymore.

Gollum: What did you say?

Sméagol: Master looks after us now. We don’t need you.

Gollum: What?

Sméagol: Leave now and never come back.

Gollum: No.

Sméagol: Leave now and never come back. Leave now and never come back!

Part of the appeal of this scene is in Sméagol appearing to have a genuine better nature. He desires to help himself and become a better person; there’s a frantic desperation to reclaim his soul. Andy Serkis plays this up in his performance, rightly acclaimed as it’s one of the finest performances in 21st century cinema, imbuing Sméagol with a fear and a desperate sadness while Gollum jeers at him. Compare this to how Tolkien writes the Sméagol/Gollum dialogue:

Sméagol was holding a debate with some other thought that used the same voice but made it squeak and hiss. A pale light and a green light alternated as he spoke.

‘Sméagol promised,’ said the first thought.

‘Yes, yes, my precious, came the answer, ‘we promised: to save our Precious, not to let Him have it—never. But it’s going to Him, yes, nearer every step. What’s the hobbit going to do with it, we wonders, yes we wonders.’

Gollum still serves the Ring, and seeks to preserve it, as he seeks to preserve himself. Sméagol is self-serving too, and fundamentally beholden to Gollum. There’s little complexity in the Gollum-Frodo relationship this way; rather than Frodo and Gollum genuinely wanting to help each other, the dynamic is simplified. Despite Frodo’s noble intentions and relatively humane treatment of his captor, Gollum fears him. Surely this can’t just be because of some refusal of grace; in part it must be due to the authoritarian tendencies of those offering Gollum grace. If redemption is conditional, can free will factor in? Gollum does not know. He has yet to decide.

Later in The Two Towers when Frodo and Sam are captured by Faramir, Gollum briefly exits the book, leaving the hobbits to develop an initially shaky but eventually sturdy rapport with the Gondorian captain (as opposed to the sequence’s controversial counterpart in Jackson’s adaptation, which radically departs from Tolkien by introducing overt political intrigue, paranoia on Faramir’s part, and an outing in Osgiliath where the Ring is nearly lost). Shortly Gollum discovers their location, Henneth Annûn, a secret outpost in a cave behind a waterfall, where he proceeds to engage in some early morning fishing by hand, likely the most content he’s been in some time (“now we can eat fish in peace”). Faramir, wishing to test the hobbits’ trustworthiness, informs Frodo and Sam that “fish from the pool of Henneth Annûn may cost [Gollum] all he has to give” as “for coming unbidden to this place death is our law.” Frodo defends Gollum, saying “the creature is wretched and hungry,” but heeding Faramir’s command that Gollum “must be slain or taken,” opts to lure Gollum into Faramir’s custody.

The subsequent events are truly weird and disturbing. In the novel, Frodo tells Gollum that his life is in danger, somewhat exaggerating the risks (which in Frodo’s view “was too much like trickery”). Gollum is immediately seized by Faramir’s men and the green light in his eyes returns: “‘Masster, Masster!’ he hissed. ‘Wicked! Tricksy! False!’” Gollum is then subjected to some stark cruelty by Faramir, who responds to Gollum’s protestations of his innocence with “Have you never done anything worthy of binding or of worse punishment?” then adding a moralizing “however, that is not for me to judge happily.” Disturbingly, the book seems to side with Faramir’s abject torment of Gollum, as Faramir offers bits of received wisdom such as “a malice eats it like a canker, and the evil is growing,” as if his actions aren’t directly contributing to Gollum’s hostility. Worse still is how Frodo seems to mainly defend bringing Gollum as his guide as a matter of practical necessity, and fails to reprimand Faramir for his cruelty.

Jackson handles this somewhat better, although he does have Frodo looking worse for it — Elijah Wood’s Frodo doesn’t warn Gollum of the presence of men before luring him away from the waterfall. The subsequent events are depicted as traumatic for Gollum, as Andy Serkis lets out an agonized and betrayed “Master!” before being subjected to a beating by Faramir’s rangers. He has a breakdown in front of them, with Evil!Gollum resurfacing (Sméagol has been in control for much of the movie), and at this point essentially defeating the better nature of Sméagol. As he’s dragged through a wartorn Osgiliath, he’s forgotten, particularly as Sam redresses Frodo on the nature of good and evil and companionship. In an amazing collaboration of Andy Serkis and Weta Digital, Gollum looks away sadly, knowing that the kindness of hobbits and Men and Elves do not apply to him.

Is it any wonder, then, that Sméagol turns on the hobbits so shortly afterward? Who amongst us would not lead our hypocritical captors into a cave where a giant spider lives? Gollum’s soul has been lost, leading them through Cirith Ungol with a coy “Yes, we must go this way now.” As Shelob besets Gollum with her webs and pointy legs, Gollum accosts his tormenter Sam, gleefully hollering “At last, my precious, we’ve got him, yes, the nassty hobbit. We takes this one. She’ll get the other. O yes, Shelob will get him, not Sméagol: he promised; he won’t hurt Master at all. But he’s got you, you nassty filthy little sneak!” (The Two Towers, “Shelob’s Lair”) Even in wickedness Gollum abides by codes and rules, semantically holding to his vow not to harm Frodo but leaping on an attempt to murder Sam. In the end, Shelob takes Frodo, Sam leaves him for dead, and the Orcs find Frodo, realize he’s alive, and capture him. The Two Towers ends with Gollum’s victory; he has avenged himself against the Baggins dynasty, those who vowed to protect him and then hurt him worst of all. In The Lord of the Rings, Gollum is the voice of the repressed and subaltern; his villainy is a type of restorative heroism. And in the end, The Two Towers is the battle he fights and wins.

Yet the moral battle here is not so clear. For one thing, it’s a trick. Tolkien tells the reader that Gollum has been planning to ditch Frodo and Sam and take the Ring from the beginning. In the “Shelob’s Lair” chapter it is revealed that “as he walked the dangerous road from Emyn Muil to Morgul Vale,” Gollum has anticipated that Shelob “throws away the bones and the empty garments” of the hobbits, and then he can get “the Precious, a reward for poor Sméagol who brings nice food.” Furthermore, Gollum is now known to have an advantageous relationship with Shelob, as “in past days he had worshipped her, and the darkness of her evil will… [cut] him off from light and from regret.” With this passage Tolkien undercuts the moral stakes of Gollum’s story, revoking Gollum’s free will and reducing him to a purely subversive force, emblemizing how the Ring’s power increases as it nears Mount Doom but removing Gollum’s agency, and thus any troubling implications of it.

In this way, Peter Jackson and company improve Gollum’s arc by highlighting his trauma at the hands of Faramir and his rangers. Before this point Sméagol seems to be in control, and eminently redeemable. It’s his abuse and torment in Ithilien that brings Gollum back into control. As Jackson’s The Two Towers ends with the skirmish in Osgiliath and the conclusion of Helm’s Deep, the bulk of Gollum’s final corruption takes place in The Return of the King. Sméagol is still vulnerable at this point, but he realizes he cannot trust the hobbits anymore, having given into Gollum’s plotting against them. At this point the two halves of Gollum have an abusive dynamic where Gollum is in control, and testing Sméagol’s loyalty. Compare an exchange of theirs in The Return of the King to the iconic Two Towers scene. While the Walsh-directed scene in The Two Towers intercut alternating angles when Gollum and Sméagol are talking, Andy Serkis delivers his dialogue here to a pond, with Gollum occupying the reflection while Sméagol stands on dry land (with the exception of one very powerful cut to Déagol’s murder, followed by a shot of Gollum on dry land, and then a change in facial expression as an in-camera transition to Sméagol):

Gollum: What’s it saying, my Precious, my love? Is Sméagol losing his nerve?? [sic]

Sméagol: No! Not! Never! Sméagol hates nasty Hobbitses! Sméagol wants to see them — dead!

Gollum: And we will … Sméagol did it once… He can do it again. It’s ours — ours!

Sméagol: We must get the Precious. We must get it back.

Gollum: Patience, patience, my love. First, we must lead them to her.

Sméagol: We lead them to the windy stairs.

Gollum: Up the stairs… and then?

Sméagol: Up, up, up the stairs we go… until we come to… the Tunnel!

It’s clear from this exchange that Sméagol’s eagerness to please is still in play, and applies to whatever party has control over him. There’s a self-serving quality to this; even when he’s helped Frodo, out of the goodness of his heart, he remains quietly (or vocally) selfish. This subtle but powerful changeability in Gollum’s psychology does wonders for him, as does Andy Serkis’ dynamic portrayal of the character. There are problems: Frodo’s compassion for Gollum ultimately becomes a liability when, in his near-catatonic state as played by Elijah Wood, he makes a series of baffling choices and is ultimately proven wrong for believing in Gollum. But the power of the relationship remains. When Gollum throttles Frodo at Sammath Naur while the hobbit begs him to remember his promise to protect Frodo, Gollum utters two words: “Sméagol lied.” Sméagol is lost, consumed by Gollum. These last two words, both a truth and a lie, consummate Gollum’s relationship with morality and reality. He is not a staid and consistent figure, no longer a person: Gollum is all id and subversion.

When Gollum resurfaces in Tolkien’s The Return of the King, the hollowness of his victory is laid bare. Upon Frodo and Sam’s arrival at Mount Doom, Gollum’s only thought is violent rage and self-preservation, wrestling the hobbits in a last ditch effort for the Ring. The quest to destroy the Ring has become an inadvertent quest to kill Gollum. He pleads with Sam, imploring him “Don’t kill us,” saying “Let us live, yes, live just a little longer. Lost lost! We’re lost. And when Precious goes we’ll die, yes, die into the dust.” Sam’s clemency in the moment, in which he lets Gollum go, is the mistake that saves the day. Gollum of course bounds into Sammath Naur, wrestles with the invisible corrupted Frodo, bites off his finger, and takes the One Ring. In his glee, he engages in a giddy victory dance, slips, and falls into the fires below. Gollum is gone. The quest for the Ring has been resolved. At his expense. Gollum is a sacrifice, a weak and vulnerable person always destined for doom. When Gandalf speaks of Gollum’s part to play in the Matter of Middle-earth, he of course means that Gollum is a useful tool, not a person in his own right. And yet Gollum constantly seeks liberation, sometimes on the terms of his captors, but ultimately falling from grace and into doom. His doom is Middle-earth’s salvation, and an indictment of all Middle-earth.

Mordor is hot and pungent. Let us venture to the outskirts. “Let us forgive him,” says Frodo of Gollum. And so we shall, by revisiting where Gollum laid his final footsteps. It is all we must ask of Tolkien’s Iscariot, the true protagonist of The Lord of the Rings.

June 19, 2021 @ 7:51 pm

For anyone who doesn’t know (as I didn’t for many years), there’s an old saying that Tolkien was riffing on with Gollum during the riddle game: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teaching_grandmother_to_suck_eggs

June 19, 2021 @ 7:57 pm

Oh shit!

June 23, 2021 @ 3:17 am

Can’t Gollum’s death be seen as a salvation of sorts? He spends his last moments, happy and content with his Precious back in his possession and then is granted freedom from his torment by his unintended fall. That strikes me as more a merciful fate then letting him die in agony and despair from the Ring’s destruction in another way.

June 23, 2021 @ 10:32 am

I think you’re right. It’s ultimately his actions and follies that save Middle-earth. It’s a bit like Borges’ short story “Three Versions of Judas,” where the villainous traitor is the one who sacrifices himself to redeem the world.