The King Of The Twentieth Century (Book Three, Part Eighteen: A Serious House on a Serious Earth)

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Released in the wake of the hit Tim Burton film, Grant Morrison scored a massive hit with Arkham Asylum.

Me? I’m the king of the Twentieth Century. I’m the bogeyman. The villain. -Alan Moore, V for Vendetta

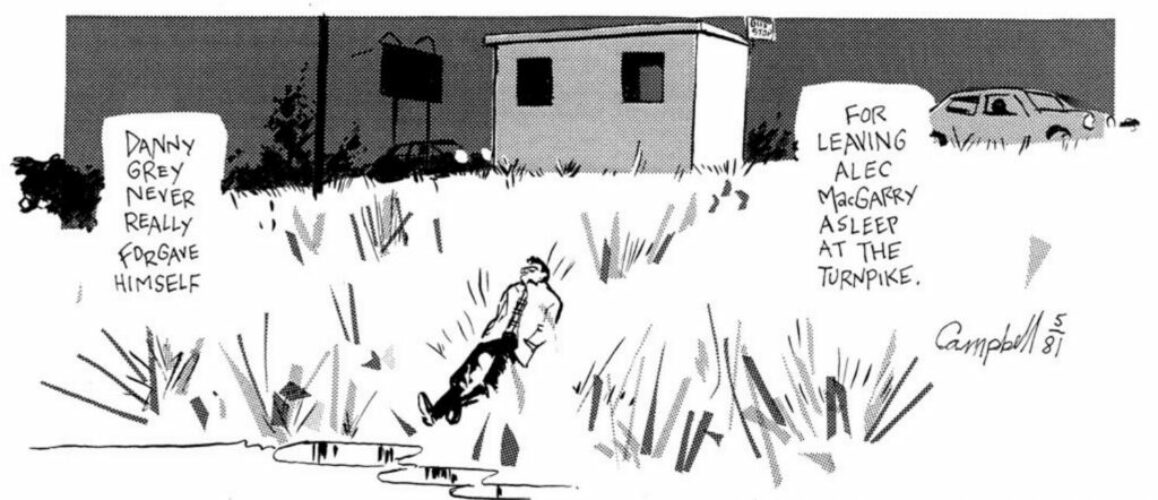

But this was poison fruit. The truth was that Morrison’s success was not their own. Arkham Asylum sold because there was a Batman movie out. To the extent that its content was what drove sales it was the lush and immediately arresting design by Dave McKean that stood out—announcing itself thunderously the moment someone opened the book to a random page. Even the legendary Gaspar Saladino’s lettering—a vivid and expressionistic triumph of an oft-unheralded aspect of comics—would have made more of an immediate impression for most prospective customers than the fact that the book was by the author of Animal Man, a critically acclaimed midlist title. Morrison made the money, and of course their later projects would proclaim them the author of Arkham Asylum instead. But it was not Morrison’s work that ensured this success. Even Morrison admitted “I don’t think it would have sold so much if people had suspected what was in it.” Which gets at what is clearly the most painful aspect of it for them: the fact that for all its sales, it got an extraordinarily rocky reception. As they wryly but pointedly noted, out of sales that were by that point around 200,000, “199,000 people regretted it.”

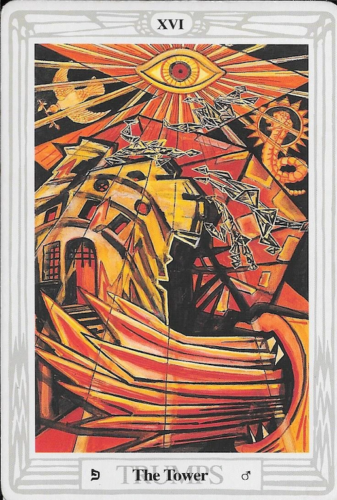

Indeed, as Morrison has tartly and repeatedly noted, the published Arkham Asylum differed in key ways from the comic they had intended. But it is worth considering the precise nature of what Morrison was attempting. Arkham Asylum was to have been a tightly interconnected set of symbols reflecting and reiterating each other so that meanings evolved through repetition. An entirely fair way to summarize this—one Morrison was surely smart enough to realize at the time—was Watchmen only for Batman. This is clear even to the level of small details—the mirror image opening and closing images, for instance, or the sequence in which the vigilante superhero is shown a Rorschach blot (he sees a bat, unsurprisingly) and subjected to other obvious psychological twists. Indeed, in a case of Morrison expropriating even Watchmen’s flaws, the incident that drives Batman to where he must engage in his mirror-fueled bloodletting is a word association test that goes to wincingly obvious places of the sort that he would eventually criticize Moore for doing with Rorschach. (“Mother.” “Pearl.” “Handle.” “Revolver.” “Gun.” “Father.” “Father.” Death.”)

The comic’s debt to Moore becomes even clearer when one looks at Morrison’s account of its reception. “At the time,” they note, “I was still drunk with the idea that people were invested in comics that were full of fantastic layers of symbolism. And obviously most people don’t even have the education to pick up on the most basic things. Which is not to say that I’m particularly educated; I didn’t go to university or anything, but I just happen to read a lot.…