They Seem Like Nice Boys (Book Three, Part 58: V for Vendetta Book Three, Movie Development)

Previously in Last War in Albion: Alan Moore’s first post-Watchmen project saw him returning to the beginning of his career to finish V for Vendetta.

“In the end, I was glad they got the ideas out but very disappointed that they blew it so badly and distorted all the Gnostic transcendental aspects that made the first film so strong and potent. If they had any sense, they would have befriended me instead of pissing me off. They seem like nice boys.” – Grant Morrison, 2005 interview with Suicide Girls

Moore’s evolution over the seven years of the project is perhaps clearest, however, in the larger thematic issues. Moore had originally envisioned V for Vendetta as an exploration of anarchism vs fascism in which all sides were taken seriously—as early as 1984 Moore talked about how he originally “ intended it to be a pretty trite piece of propaganda. But it didn’t work like that – it came out superficial and hollow. I realized that the only way to treat it honestly was to take the fascist characters and get deeply involved in their mentality.” It was not, obviously, that Moore was without any moral investment in the debate between anarchism and fascism—a debate Moore has suggested is both the absolute heart of all political debate and one that is in fact “as much a matter of the emotions and spirit as they are matters of abstract intellect and politics. Maybe even more so.” Given this, and especially given his summary of the debate as “should we be ruled,” there is only ever one position that Alan Moore has ever taken at any point in his life. And the idea that V for Vendetta is particularly ambiguous in what it favors between fascism and anarchism is, charitably, strained.

All the same, there were moral ambiguities to resolve. Any ending was going to necessarily resolve some of the shades of gray, just based on what the plot beats were—who got to win, who got big hero moments on the way out, etc. And so Moore had decisions to make. He’s suggested that the bulk of these were already made, noting that “There were no major plot changes from the way I laid out the story when we were doing it for Warrior,” but in the same interview he noted that “the tone [of Book Three], I think, is subtly different.” Speaking about it some years later, asked in an interview about V’s tactics, Moore clarified that the use of violence “is something which I don’t sympathize with,” and that “in Book Three, it’s finally decided that no it isn’t; that killing people is always wrong; and at that point the initial hero V stands down and lets a non-violent person take over the role.”

It’s easy to read this transformation in light of Watchmen. It is not clear when, exactly, Moore embraced nonviolence. His earliest explicit endorsement of it comes in 1987, when he expressed a “deep aversion to all forms of violence and war,” but it’s a position one can imagine him taking at any point in his life. And yet it’s hard not to notice that Moore was writing this coming off of a lengthy exploration of the aesthetic endpoints of superhero narratives that found fascism sitting coldly at every terminus. This could not have surprised him—as early as 1983 he noted of superheroes that “there is a lot of fascism in the idea. Somebody said the difference between Superman and a mass murderer is in fact very little—they’re both people who assume they have the power and assume they have the right to inflict their own conception of justice on the world. There is a lot of really strange morals there which are really interesting to explore.” But there is still a clear sense in Watchmen of a man turning away from the heroic vision of man who will take dramatic action to save the world in favor of a smaller, more human way of cutting the Gordian knot.

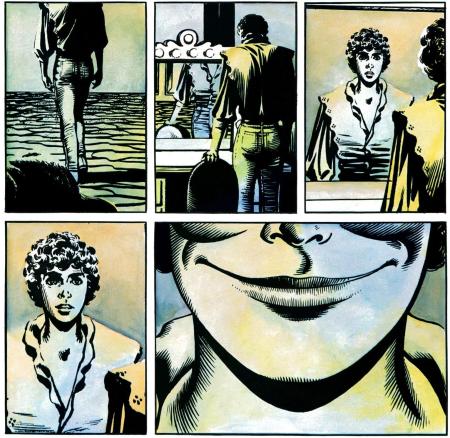

That Evey should eventually take over the role of being V was surely planned from the beginning of the story—even without Moore’s claim that there were no major plot changes, the idea of Evey as V’s successor is too thoroughly set up to have been a late invention. But done in 1988, as Moore’s last act before walking away from DC, the tone changes to something that simply could not have been imagined by a man for whom the strip was a bid for greater financial security than his pen-named strips in Sounds and The Northants Post could offer. It is hard not to see the Alan Moore of 1981 in V—the ostentatious and romantic revolutionary poet, ever the showman. But just as Blake turned from a belief in the fiery revolutions of Orc towards something more potent and nebulous as his ambitions shifted from a career that he imagined would revolutionize British art into a more modest one that actually did, so too did Moore’s ambitions change. He had been to the great castle within comics, become a star of the medium, and realized its promises were hollow. Moore could easily have positioned himself as the “comic book messiah for the 1990s” he half-joked about being in the England Their England documentary. Instead he’d walked away, and decided to be a different sort of revolutionary.

Given that, it’s hard not to see flashes of self-critique in Evey’s usurping of V—her angry retort when V declares that he’s “waiting for the man” that “if that’s another… it is, isn’t it? It’s another bloody quote! I’ve heard it on the jukebox. V, I hate this. All our conversations turn into crossword puzzles!” seems like more than just a rejection of V’s smugly superior allusiveness, but of the man who’d titled Swamp Thing issues things like “Another Green World,” “Strange Fruit,” and “Loving the Alien,” and named every chapter of Watchmen after an allusive and symbolic quotation. And if Evey gave V a viking funeral, well, surely the conclusion of V for Vendetta was nothing less than Moore doing the same thing for the first decade of his career—a spectacular sendoff that would bring this version of “Alan Moore” to an end and make space for a new one.

Except, as he knew well, nothing ever ends, and Moore would spend the decades that followed making an increasingly grudging series of returns to his first act. Part of this was simply that the works in question did not fade from the popular consciousness. V for Vendetta was completed under the same contract as Watchmen—as Moore recalls it, “I was so pleased with the deal with Watchmen, that I suggested to David Lloyd that we do the same thing on V for Vendetta—which was, again, something that we owned and that we wanted to carry on owning.” Except that, just like Watchmen, in practice this contract meant that DC owned the comic in perpetuity, and it went on to be a steady performer for them in its trade paperback form—not as massive a seller as Watchmen, but perpetually in print as a venerable and oft-cited classic. And so, inevitably, there was interest in the film rights, which were secured by producer Joel Silver alongside the rights to Watchmen around when DC’s version of the comic started publishing. The film toiled in a typical development hell—the earliest script draft, by Hilary Henkin, dates to 1991, and took a bizarre semi-comedic turn, with touches like having the Finger’s building be shaped like a literal finger.

Some time in the middle of the 1990s Lana and Lily Wachowski took a crack at the movie—a review of their first draft of the screenplay dated in 2001 called it “lugubrious, flat, uninspired, disorganized and, much to my surprise, devoid of even brainless, trivial adventure.” The siblings instead went on to direct The Matrix, the last great work of cyberpunk, which Grant Morrison would insist was plagiarized from The Invisibles, a claim that mostly reveals that they’d never seen Ghost in the Shell. During the production of the film’s two sequels, the Wachowskis revised their old screenplay and offered it to their assistant director, James McTeague, as an opportunity to move up to directing his own features. He accepted, and the resultant film saw release in 2006 after a premiere in late 2005.

V for Vendetta was the third film to be adapted from Moore’s comics. Moore had been happy enough with the first, 2001’s From Hell, taking the money and staying away from the film. As he put it, “”I did not wish to be connected with it, and regarded it as something separate to my work. In retrospect, this was kind of a naïve attitude.” But his attitude shifted in the wake of 2003’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, particularly when the film became the subject of a copyright troll lawsuit alleging that it was plagiarized from a rejected mid-90s screenplay called Cast of Characters. This lawsuit featured the particularly absurd claim that 20th Century Fox had hired Moore to write the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen comic as a cover story for the subsequent plagiarism of the screenplay, which resulted in Moore undergoing a ten hour deposition for the lawsuit, an experience that cannot have been pleasant for anyone involved. Moore, for his part, noted that “If I had raped and murdered a schoolbus full of retarded children after selling them heroin, I doubt that I would have been cross-examined for 10 hours.” And when 20th Century Fox subsequently settled the suit out of court, Moore viewed it as a tacit admission of guilt, including the claim that he’d been a knowing party to the supposed plagiarism.

This was sufficient to sour Moore on the film industry entirely, and so, deciding that anything worth reacting to “was worth overreacting to,” he vowed not to approve any more film adaptations of his comics whatsoever. This policy, however, was not sufficient to stop V for Vendetta given that Warner Brothers held the rights as the corporate parent of DC. Which meant that Moore’s feelings about the film quickly entangled with his increasingly strained relationship with DC, who had spent the preceding seven years awkwardly serving as Moore’s publisher after their acquisition of Wildstorm, a situation that had gradually unraveled as his promised editorial independence was steadily undermined.

The situation came to a head in March of 2005 when Joel Silver claimed that Moore was “very excited about what [Lana] had to say and [Lana] sent the script, so we hope to see him sometime before we’re in the U.K.” Silver subsequently claimed that he was in fact basing this assessment of Moore’s enthusiasm on a lunch he’d had with Moore back in the 1980s when he acquired the film rights. This is, to say the least, a puzzling explanation for a statement that specifically focused on a phone call between Moore and Lana Wachowski, and one is left to suspect that the real explanation was simply that Silver was playing the hype man and offering boilerplate assurances on the assumption that authors are always excited about the big Hollywood royalties coming their way, and that he did not fully appreciate the implications of saying this about Alan Moore.

The reality, in any case, was that Lana Wachowski had called Moore only to be politely rebuffed on the grounds that Moore wanted nothing to do with the film. And so, in a development that could not have surprised anyone who knew him, Moore hit the roof, incensed by Silver falsely using his name to promote a film he didn’t actually want to exist and felt he had been cheated out of his right to veto. Sending word through his editor at Wildstorm, Moore demanded a retraction and an apology. Silver claims that he in fact called Moore to apologize only to be repeatedly told “I’m going to hang up on you if you don’t stop talking to me,” but other reporting suggests that Paul Levitz tried and failed to elicit such an apology, and Silver’s credibility is already debatable.

In any case, the retraction never happened, in part because of Moore’s demand that such a retraction be given similar weight to the original statement, which was not really possible given that the original statement came in the announcement that production had started on the film, and Moore responded by pulling League of Extraordinary Gentlemen from DC and began inserting a clause into all contracts nullifying it if DC ever bought out the company, while also insisting on having his name removed from the credits of the film—an escalation of what he did for the 2005 Constantine film, where he simply refused the money and had it divvied up among the co-creators.

Moore also began a modest press campaign attacking the movie, telling the New York Times, “I’ve read the screenplay. It’s rubbish.” Elsewhere he declared that the script “was imbecilic; it had plot holes you couldn’t have got away with in Whizzer And Chips in the nineteen sixties.” He took particular exception to the film’s handling of the story’s politics, complaining that “There wasn’t a mention of anarchy as far as I could see. The fascism had been completely defanged. I mean, I think that any references to racial purity had been excised, whereas actually, fascists are quite big on racial purity.” More substantively, he complained that his story had “been turned into a Bush-era parable by people too timid to set a political satire in their own country. In my original story there had been a limited nuclear war, which had isolated Britain, caused a lot of chaos and a collapse of government, and a fascist totalitarian dictatorship had sprung up. Now, in the film, you’ve got a sinister group of right-wing figures — not fascists, but you know that they’re bad guys — and what they have done is manufactured a bio-terror weapon in secret, so that they can fake a massive terrorist incident to get everybody on their side, so that they can pursue their right-wing agenda. It’s a thwarted and frustrated and perhaps largely impotent American liberal fantasy of someone with American liberal values [standing up] against a state run by neo-conservatives — which is not what V for Vendetta was about. It was about fascism, it was about anarchy, it was about [England],” suggesting that “if the [Wachowskis] had felt moved to protest the way things were going in America, then wouldn’t it have been more direct to do what I’d done and set a risky political narrative sometime in the near future that was obviously talking about the things going on today?” [continued]

January 9, 2023 @ 11:18 pm

Somebody said the difference between Superman and a mass murderer is in fact very little—they’re both people who assume they have the power and assume they have the right to inflict their own conception of justice on the world. There is a lot of really strange morals there which are really interesting to explore.

Sounds like the seeds that would blossom in Olympus had already been planted and begun to sprout, like the corpse in Stetson’s garden.

January 15, 2023 @ 7:04 pm

There are, I think, some pretty noted similarities between The Invisibles and The Matrix that aren’t so easily dismissiable. I just wouldn’t go as far as calling it plagiarism, as even Morrison walked back on that in “Anarchy For The Masses”.

August 3, 2025 @ 6:18 pm

You need to put spoiler alerts!! Why would you put a panel from the end of the comic, complete with a caption spoiling the ending (Evie becoming V)

August 3, 2025 @ 6:27 pm

Because the comic came out thirty-six years ago and if you don’t want it spoiled then you probably shouldn’t read criticism about it before reading it.