Ghost Photographs (Book Three, Part 11: Vesica Piscis, Dave McKean)

CW: Sexually explicit imagery

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Grant Morrison’s script for Arkham Asylum focused on the geometric image of the vesica piscis.

I find myself grasping for my roots, awkwardly. And I wonder what my grandparents would think of me, were they to meet me today. Ask their shades about me and I imagine they would pull ghost photographs from their wallets and handbags, show you a solemn child with huge hazel eyes. -Neil Gaiman, Mr. Punch

Euclid’s Elements begins with one, using it to construct an equilateral triangle. Indeed, one can use it to construct a myriad of basic shapes—the square, pentagon, and hexagon can also be constructed from it.

Within the Pythagorean religion the number one, represented by the circle and called the monad, was considered sacred and holy. The vesica piscis thus represented the dyad, combining as it did two circles. The generative properties outlined by Euclid, then, become the product of copulation, a meaning further emphasized by the visual similarities between the vesica piscis and the vagina. This mystical association, obvious as it was, served as a largely cross-cultural bit of sacred geometry.

Separately, however, the vesica piscis became a Christian symbol. By extending the lines on one apex one gets a distinctly fish shape, which meshes with a wealth of Biblical imagery. More mystically, various numerological associations between the proportions of the vesica piscis and the Bible are attested, if dubiously. The shape is also closely related to the ogive, which is essentially a vesica piscis with flattened sides, and which serves as the geometric underpinning of the gothic archway.

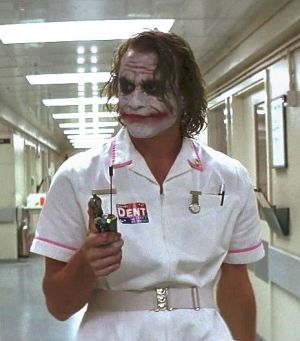

For their part, Morrison ties the symbol to the larger body of symbolism in Arkham Asylum, using the fish symbol to relate it to the Moon Tarot card according to Hermetic lore while also drawing a Christ-Osiris link (familiar in Crowley) to bring up descent to the underworld imagery. Indeed, there’s an entire line of fish symbolism in Arkham Asylum. Clown fish make regular appearances, gesturing both to the Joker and to a theme of sexual ambiguity that got downplayed when Warner Bros. corporate refused to allow the comic to depict the Joker dressed as Madonna on the grounds that it might lead people to assume that Jack Nicholson was a cross-dresser, a fairly astonishing case of reaching the right decision for the stupidest reasons possible. (Morrison later rued that “in the end it was Heath Ledger who immortalized the tranny Joker in 2008’s The Dark Knight, vindicating my foresight.”) And at another point they have Amadeus Arkham reflect on the French term for the victim of an April Fool’s prank, poisson d’Avril, while also connecting the vesica piscis to holography and the theories of David Bohm.

The bulk of the discussion of the vesica piscis in Morrison’ script comes around a sequence roughly halfway through the book where Batman, shaken by flashbacks to his parents’ murder, snaps himself out of it by pushing a shard of broken mirror into his hand. Morrison breaks off into a several paragraph parenthetical, laying out for McKean the symbolism of the vesica piscis, making an aside about a 16th century book of Nottinghamshire folklore they discovered that contained several sequences that closely mirrored events in Arkham Asylum, and finally gesturing at the larger structural themes of the book. Clearly recognizing this was a bit much, not least because of its complete lack of relevance to how McKean should draw Batman pushing a shard of glass into his hand, Morrison then jokes, “Yeah, so Batman is here inflicting upon himself one of Christ’s wounds and it’s all got something to do with fish, okay?”

The resulting scene, however, was not what Morrison had hoped for. As they put it when annotating the script, it “was intended to show Batman pricking his palm with glass to shock himself out of Joker-induced trauma. In Dave’s hands the scene wound up as an unforgettable, apocalyptic bloodletting which would surely have rendered Batman’s hand entirely useless for the rest of the book, and possibly the remainder of his useless life.” Perhaps a bit richly given that their lengthy account of Christian architectural fish symbolism is literally right at the top of the page, they even go so far as to describe their description as one of a “simple scene.”

This, however, was not even the biggest change McKean made related to the scene. Across the entire book McKean does not once follow Morrison’s instructions to draw a vesica piscis. On multiple occasions Morrison’s script stresses that the architecture of the asylum was to be based around the vesica piscis, directing in two scenes that McKean should draw Amadeus Arkham holding an image of the vesica piscis. McKean drew none of this; across the entire graphic novel the vesica piscis appears only on an introductory page before the title page or the beginning of the story and in a decidedly un-emphasized manner in the denouement. This key symbol at the heart of Morrison’s sacred geometry was by and large left out.

This is clearly something of a sore spot for Morrison, who spends a fair portion of their annotations highlighting all the moments when McKean did not do things as they directed. Indeed, they’ve gone so far as to blame the failure of their collaboration with McKean for the comic’s deficiencies, explaining that “I was doing stuff that was so symbolic, and then Dave was doing his own stuff that was symbolic, we eventually had two symbol systems merrily fighting each other, with the reader trying to make sense of it all,” and suggesting that “it’d be better if we had more of a sense of Batman moving through a specific location, and that isn’t there. I wanted it to be so that every single bit of dirt on he wall was there. It wasn’t that, and there wasn’t any sense of him moving through a particular architectural space, which is what I’d imagined. So I think the momentum of it was dissipated.”

There are many factors in the failure of Morrison and McKean’s collaboration. But at the heart of it is simply that Dave McKean was never an artist that was going to draw something in the style Morrison was asking for, a fact that would have been immediately obvious to anyone who looked at his work. McKean had pitched alongside Neil Gaiman at the February 1987 meeting. Gaiman was very much the lead figure in this meeting—he describes having to cajole McKean, who’d had a failed trip to New York to pitch to American publishers in 1986, into even taking the meeting. “Poor Dave was just walking around behind me going, ‘They don’t mean it.’ I’m going, ‘Sshhhh. Don’t look down. We’re okay.’” Berger had read a sample script, “Jack in the Green,” which Gaiman had consulted with Alan Moore on how to approach writing and was impressed by it, and of course Gaiman, like Morrison, came with Moore’s recommendation and approval. But in Gaiman’s account, the turning point at the meeting came when “they looked at Dave’s art and suddenly Dick Giordano took us very, very seriously.”

The art which they showed was a pre-release copy of a forty-eight page graphic novel entitled Violent Cases. This project emerged out of a never published British magazine entitled Borderline. Spearheaded by Hunter Tremayne, who had promoted several similarly failed ventures in the past, the magazine served mostly as an occasion for an emerging generation of creators to meet each other, drawn in by Tremayne’s aggressive advertising for the doomed venture. Gaiman was to have written three strips for the magazine, while McKean was set to draw two. In the course of the venture’s slow collapse Paul Gravett of Escape sought to write an article on the venture, meeting both Gaiman and McKean and, impressed with both of their work, offering them the opportunity to do a short story for Escape. In an impressive bit of hubris, Gaiman turned around and pitched a forty-eight page graphic novel, which Gravett accepted. (“To his credit,” Gaiman recalls, “he didn’t even blink.”)

Violent Cases began life as a short story that Gaiman had written at a writers workshop. He had attended the workshop the previous year and seen his story go over poorly, but in the course of it, particularly by listening to the comments of John Clute and Gwyneth Jones, who both had significant careers as critics, “learned how to read, which really changed things when I started to write fiction after that. I was starting to learn and understand the use of subtext, the use of metaphor, he use of allusion—the tools of fiction. Because I’d seen how these guys did it. I started to understand something that only crystalized about eight months later when I started writing Violent Cases. That honesty is important. All of my fiction had been using other people’s voices. And there was a point around then that I started to realize that all one has to offer as a writer is oneself. All that makes me different from all the writers out there is me. Violent Cases was the first thing that did that.” When Gravett pushed him to collaborate with McKean, Gaiman suggested the story.

Notably, no effort was made to revise the story into a comics script. This was not because Gaiman didn’t know how to write one yet—he’d been working with Alan Moore at learning that—but because, as he put it, “I didn’t know how to write for Dave, to get the best out of Dave.” The irony, however, is that this proved to be the exact way to work with McKean; indeed, it would become a characteristic element of their collaborations with Gaiman backing off and giving McKean considerable freedom in structuring the story, either scripting in prose and then collaborating further with him after he’s done breakdowns and revising the script accordingly, as they did on both Violent Cases and its quasi-sequel Mr. Punch, or, as they did on their later collaboration Signal to Noise, an idiosyncratic format unique to their collaboration whereby Gaiman “talked everything through with him way ahead of time, and then I just gave him some words, with a few comments in brackets. And he went away and turned that into a comic.”.

That McKean should benefit from (and indeed require) such an idiosyncratic writing style is no surprise, however, when one looks at his style. This was a flexible thing—his cover to Violent Cases was a collage of drawing, found objects, and photographs that genuinely looked like nothing else in comics. His interiors for Violent Cases were simpler than this—the book was originally printed in black and white, while McKean, perhaps anticipating that there might be later versions, worked in a subdued palate washed with blues and sepias. But the strange abstraction of his style still remained—McKean could still collage in photographs and reproductions of documents, and could bleed seamlessly across a page or even a panel from photorealism to cubist-inspired representations to pure abstraction. His page compositions were ambitious, formally complex, challenging the notions of panels and space. All of the techniques he’d go on to use in Arkham Asylum were already in place, just in a muted color palate.

This suited the material of Violent Cases. Indeed, for all Gaiman’s protestations about not knowing how to craft a story for McKean, the basic selection of Violent Cases was perfectly tailored to his artist. Gaiman’s story is at its heart about childhood memory; a self-professedly hazy recounting of incidents that occurred when he was four, presented in a way that maintains his childhood naïveté while providing enough puzzle pieces for adults to reassemble the bulk of the picture. From the narrator’s perspective (and McKean draws the narrator as Neil Gaiman), it is the story of when his father injured his shoulder trying to drag him up the stairs to bed (“I would not want you to think that I was a battered child,” Gaiman begins his narration) and he went to an osteopath who had previously worked for Al Capone. After a couple of visits in which Gaiman learns a few scattered things about gangsters, including that they “had tommy guns, which they kept in violent cases,” Gaiman encounters the man again while hiding from the magician at a children’s party. They talk more, and Gaiman is told a disturbing story of Capone tying a bunch of men to chairs and beating them to death with a baseball bat, and then the magician and some other men come and take the osteopath away in what the reader surmises is a hit.

The story exists in a liminal space between truth and fiction; as Gaiman puts it, “I’d compare it to a mosaic; all the little red tiles are my memories, but a red tile may be half a sentence, the other half is fiction… The story, as you go through, drifts further and further away from the truth, so for example the first gangster story you get is the story of Legs Diamond, it’s a true story. The next stuff about being buried in silver coffins, has elements of truth in it, but I’ve exaggerated and played around with it. Then you get the stuff about the party; it’s not true at all. [continued]

June 8, 2021 @ 12:26 pm

Dave McKean isn’t my favourite artist, nor do I think his style works for most sequential stories, but I like it on occasion. I do think he is a very positive figure to exist in the mainstream, encouraging experimentation and a closer relationship with modern art than any other artist. I’m not sure someone like JH Williams III would have the career he has without works like Arkham Asylum or artists like McKean.