Morrison is blunt about what happened: “Alan Moore had it spiked. He said it was never to be published,” an event Morrison credits for the “slight antagonism” that exists between the two creators. Morrison goes on to claim that Skinn, following his falling out with Moore, “asked me to continue Marvelman,” an opportunity he was tremendously excited by, but that Morrison, when he wrote to Moore asking for his blessing, received back “this really weird letter” beginning “I don’t want this to sound like the softly hissed tones of a Mafia hitman, but back off” and threatening Morrison’s future career if he carried on.

This account of events was flatly denied by Moore three years later in an interview with Lance Parkin for his biography of Moore, saying that it “has no bearing upon reality at all” and defying anyone to produce such a letter. Moore recalled Morrison’s script, saying that “Dez had rather sprung it on me out of the blue, and it didn’t fit in with the rather elaborate storyline that I was creating,” and explaining that he was “almost 100 per cent certain that I never wrote any kind of letter to Grant Morrison, let alone a threatening one,” with Skinn separately clarifying to Parkin that for his part, “I never saw or asked to see the letter Grant got,” but that he “enthusiastically sent Grant’s wonderful little cameo story up to Alan Moore, ill-aware of his growing possessive paranoia.” It is worth noting, however, that Moore and Skinn are, in these interviews, conflating what Morrison depicts as two separate events – Moore’s spiking of Morrison’s spec script, and the separate instance of Morrison being offered the opportunity to take over the main Marvelman strip.

|

Figure 672: Warrior #12 featured a wordless

five-pager starring Young Marvelman. (Written

by Alan Moore, art by John Ridgway, 1983) |

One significant discrepancy arising among these accounts is the question of exactly when Morrison’s spec script arrived. Skinn recalls the script coming after Moore had left Marvelman, which would place it in August of 1984 or later. But Moore’s departure from the strip had been a quiet thing that was not publicly announced, and when Skinn did make a public statement acknowledging that Warrior was no longer publishing Marvelman in an editorial spread out over the final two issues, he gave the impression that the problem was Marvel’s legal action over the Marvelman Special and not the fact that he’d fallen out with the writer, a situation that would not really have suggested to Morrison that there was a vacancy to be filled. Given that the detail of Morrison submitting “October Incident: 1966” in response to Moore’s departure comes entirely from Skinn, as opposed to from Morrison himself, it seems on the whole more likely that Morrison was simply pitching a fill-in story akin to the five-page “Young Marvelman” story in Warrior #12 or the “Vertigo” and “Vincent” installments of V for Vendetta, this being, if nothing else, a far more reasonable thing for a writer looking to break in to pitch, as Morrison would surely have realized based on his previous industry experience.

Notably, Skinn, Morrison, and Moore are all in agreement over how Morrison was notified that “October Incident: 1966” would not be used, with the news being relayed by Skinn. But the reasons for this are trickier. Moore’s explanation – that the strip did not fit with his storyline – is largely unpersuasive – nothing in “October Incident: 1966” is difficult to reconcile with the rest of Moore’s story, and Morrison took care to set it in a period where nothing was really going on in Moore’s timeline, with Young Marvelman being dead and Marvelman proper in his amnesiac phase. Skinn’s explanation that Moore was jealous and paranoid fits with his general depictions of Moore, but this also means that it fits too heavily into the general pattern of Skinn denying that he’d done anything in the least bit unreasonable in his dealings with Moore, which, given that Moore was one of a half dozen major names in British comics to have been driven away from Warrior due to some aspect of Skinn’s handling of the business side, is not entirely credible either.

|

Figure 673: Marvelman eventually

returned in the US under a new title

via Eclipse Comics in 1985. |

But if Moore was feeling a bit paranoid about Skinn’s suggestion of taking on a new writer for the strip it was hardly difficult to understand why. This period coincided with the negotiations for the deal that would eventually bring Marvelman to US publisher Eclipse Comics under the title Miracleman. Given that Skinn had by this point lost almost all of the impressive talent that had launched Warrior, with only Alan Moore, Steve Moore, and David Lloyd remaining from the original masthead, and given that Moore and Skinn had an increasingly fractious relationship, Moore would hardly have been unreasonable in fearing that Skinn was looking, in effect, to experiment with the possibility of replacing him with a writer he might have an easier time controlling. A firm line in the sand to avoid any sort of precedent for people other than him writing Marvelman would have been a prudent defense against this possibility, and one that he could readily enforce given that, under the then-current understanding of the copyright situation, he owned a share of the character.

But this in turn raises a major question about Morrison’s account of events, specifically his claim that he was offered the opportunity to take over as the regular writer of Marvelman after Moore’s departure. Simply put, this seems virtually impossible. For one thing, it is notable that neither Skinn nor Moore offer any support for the claim, instead treating the question of Morrison and Marvelman as a topic consisting purely of the script to “October Incident: 1966.” For another, it does not fit the established timeline of events for Marvelman/Miracleman at all – the idea that Skinn was simultaneously negotiating a US continuation of the comic with Eclipse (a deal signed in September of 1984, the month after the last Moore/Davis Marvelman strip was published) and attempting to negotiate a continuation in Warrior with a completely unknown and untested writer is ridiculous on the face of it. Skinn stood to get far more money out of a US sale, that having always been a major part of the Warrior business plan, and would surely not have endangered that deal by offering Morrison a job, especially given that it wasn’t his to offer in the first place. The Marvelman copyright was at the time universally understood to be split among Skinn, Moore, Davis, and Leach, which meant that three people beyond Skinn would have had to sign off on the idea of him giving the strip to a new writer, at least one of whom, Alan Moore, was clearly not going to agree to that.

And yet Morrison’s recollection of events is shockingly thorough, complete with the “softly hissed tones of a Mafia hitman” line, which, it must be said, is a characteristically Moorean turn of phrase. Could Moore have separately reached out to Morrison over “October Incident: 1966” in order to warn him off of pitching for other people’s characters? This would have been a strange course of action for Moore, but he had only recently met Morrison at the October 1983 Glasgow Comics Mart and given him career advice, and it is at least theoretically possible that he continued to do so. If such a letter did exit, however, it is worth asking how fairly Morrison is capturing its tone and content. The “Mafia hitman” line sounds like Moore, but it sounds like Moore making a sardonic joke akin to his description of Scotland as a place where “incest, murder, and cannibalism” are “still very much a part of everyday family life.” In other words, even if one does give Morrison the supreme benefit of the doubt and allow that, despite clearly inventing a job offer from Dez Skinn that could never have existed, he really did receive the letter described, it seems more likely that Moore was offering sincere advice on the wisdom of attempting to interject one’s self into someone’s ongoing and creator-owned project than that he felt compelled to separately attempt to intimidate an unknown writer he’d already had Dez Skinn tell off. And, ultimately, while the Mafia hitman line sounds a bit like Alan Moore, so does “the only answer is the sound of dream thunder echoing down the days as the memories come stealing… memories of fire in the sky and of glory that blazed white as the sun on the night the old dragon was cast out of heaven.”

|

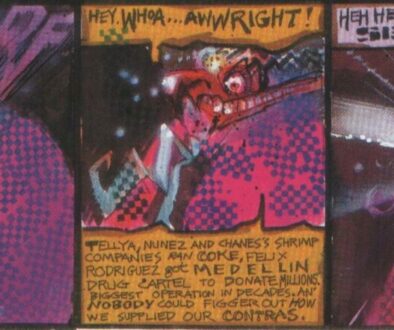

Figure 674: The opening panel of The Liberators made it fairly clear

what the appeal of the strip was meant to be. (From Warrior #22, 1984) |

But whatever the details of what happened to Morrison’s “The October Incident: 1966” script in 1984, Dez Skinn was still in dire need of new writers, and so tapped Morrison to take over writing of a strip called The Liberators for Warrior #26. The Liberators had debuted in Warrior #22, with a Skinn-penned a story called “Death Run” that featured a team of rebels led by a scantily clad female leader. The story juxtaposed action shots of the rebels’ progress with captions from an unseen figure directing them on what to do – a figure revealed at the end of the story to be the heroine’s brother, who has been captured and is being converted into a “wardroid.” The story ends with the woman blowing up the base, herself, and her already lost brother.

|

Figure 675: Morrison takes a more structurally interesting approach to

The Liberators than Skinn did, incorporating unusual transitions and panel

structures. (Written by Grant Morrison, art by John Ridgway, from “Night

Moves” in Warrior #26, 1985) |

Morrison’s story, “Night Moves,” serves as a prequel to “Death Run,” and is, it must be said, a reasonably impressive return to comics from Morrison. Certainly it’s the second best thing in Warrior #26 by a considerable margin. Morrison immediately set about improving the property, taking care of business Skinn had overlooked like bothering to give the characters names. Playing on the post-apocalyptic punk aesthetic developed by artist John Ridgway for the characters, Morrison gave the characters a slightly idiosyncratic dialogue style, not so strange as to be distracting, but enough to give the strip a sense of texture – things like, “I’ve been around and over, talking with stones. This is some bad place here, Shanni.” And Morrison repeats his effective imitation of Moore’s caption boxes, giving his story a suitably ominous opening narration (and one that owes no small debt to Moore’s work on Swamp Thing): “The darkenss is coming. An animal bursts into being, realizes its lungs are not made to breathe oxygen, and dies silently. The sky is a sullen, bruised red as the sun goes down. The darkness is coming.” The result is a credible action strip helped considerably by the fact that it has the reliably excellent John Ridgway on art duties.

|

Figure 676: A scene of torture and mind control

of the sort that is common in Morrison’s later work.

(Written by Grant Morrison, art by John Ridgway, from

“Angels and Demons,” from Comics International #67,

1996, written/drawn 1985) |

A second Morrison-penned installment of The Liberators, entitled “Angels and Demons,” was also prepared, but due to Warrior going under did not see print until 1996. This strip continues to build on the universe of The Liberators, jumping among three separate groups of characters in its six pages. The bulk of the stories features the main group of rebels being attacked by a Wardroid, while separate sections follow the character of Frisk, who has a strange flashback to what appears to be the twentieth century while scavenging through the ruins of Westminster, and a scene showing the conversion of someone into a Wardroid. The latter section, with one of the villains musing, “how must it seem to surrender the tracks and pathways of your mind to our searching fingers? To feel thought sparks retreat along neural branches down into the lightless brain root,” anticipates numerous images in Morrison’s later work, from the interrogation of King Mob by Sir Miles in The Invisibles to the mind control fetish erotica of “The Story of Zero” to the adventures of Max Nomax in Annihilator. The former, on the other hand, gestures towards further complexities in the vast and never realized shared timeline of the Warrior strips, not least in the presence of a line of dialogue within the flashback, as one character says, “we’re the children of the project. We’re the coming race… the Supermen,” a line that seems to gesture to the Nietzschean rhetoric of Dr. Gargunza in Moore’s Marvelman, who names his superhero project Project Zarathustra, and, prior to stumbling upon an old Captain Marvel comic and taking inspiration from it, referred to the Marvelman family as his “over-men.” (The Nietzschean roots of Moore’s Marvelman were also, it should be noted, name-checked in “October Incident: 1966.”

To be sure, the strip still has problems. The world of The Liberators feels too big, and like there’s a surplus of smaller good ideas masking the lack of an actual hook or concept for the series. But this is hardly Morrison’s fault. “Death Run” gave him a meager foundation to build on – it was basically a Future Shock that Morrison was told to somehow build an entire continuing story around. Morrison’s work on The Liberators does more than could be reasonably expected with the property, and it’s clear he’s giving real and intelligent thought to the genuinely difficult topic of how to transform the story into something functional. It is also worth stressing the basic ignominy of the job description: Skinn was at this point simply creating concepts, writing mediocre and vague first installments, and then handing them off to other writers to develop. But if any of the concepts broke out as V for Vendetta, Marvelman, and Laser Eraser and Pressbutton were on the brink of doing, it would be Skinn who would be their legal creator and who would reap the bulk of the benefits, even as writers like Morrison did the actual work of taking Skinn’s half-formed ideas and making them into things anyone cared about. Skinn, who to this day profits from the sale of the V for Vendetta Guy Fawkes masks despite his sole contribution to the story being asking David Lloyd to do a 1930s mystery strip and approving Alan Moore as a writer for said strip, was by this point clearly taking his self-appointed role as the British Stan Lee to a crudely logical conclusion. The only difference was that Lee was always capable of turning a profit off the exploitation of his creative partners, whereas Warrior went under after its twenty-sixth issue, meaning that Morrison, despite his obvious talent would have to wait until the next year for further opportunities in comics to present themselves.

There is, however, still one more detail of Moore’s engagement with Warrior to cover – a pair of two-part stories published under the title The Bojeffries Saga. [continued]

March 20, 2015 @ 7:00 am

"They were friends once, these creatures of near unimaginable power. Now, horns locked, they fight to the death in the pounding rain. There is passion here, but not human passion. There is fierce and desperate emotion, but not an emotion that we would recognize. They are titans, and we will never understand the alien inferno that blazes in the furnace of their souls. We will never grasp their hopes"

Certainly sounds like Moore and Morrison. I had no idea that the time around the demise or Warrior was so complicated.

March 20, 2015 @ 5:15 pm

The death of a Warrior is always a time fraught with terrible complexity. The knee-bend from on high, nature's Miracle whirling into the dust… one last gasp, and the beast is silent.

March 23, 2015 @ 8:09 am

We need some sonorous heavy music for this scene, bass laden stirring strings, fading off into a leaden sky.

December 16, 2020 @ 3:23 am

This is a helpful assistance, I truly like it, much obliged for the data you share!