Wuthering Heights

I’ve been admiring Christine Kelley’s Dreams of Orgonon since before either of them were called that. It’s smart, insightful music criticism that lived up to its obvious debt to Chris O’Leary’s Pushing Ahead of the Dame and was no small influence on my own decision to make a song by song Tori Amos blog my next project. So when I needed someone to fill in for a few months while Jack wrote his book, asking her to crosspost her work to our site was the obvious choice. And when it became evident that her first post for us would be Kate Bush’s first big hit, well, that just seemed like destiny. It’s my absolute pleasure to give Christine a bit of a boost and to have her on the site. If you want to read the story thus far, her blog archives are over here. But for now, welcome to the site, let’s get on with it. -El

I’ve been admiring Christine Kelley’s Dreams of Orgonon since before either of them were called that. It’s smart, insightful music criticism that lived up to its obvious debt to Chris O’Leary’s Pushing Ahead of the Dame and was no small influence on my own decision to make a song by song Tori Amos blog my next project. So when I needed someone to fill in for a few months while Jack wrote his book, asking her to crosspost her work to our site was the obvious choice. And when it became evident that her first post for us would be Kate Bush’s first big hit, well, that just seemed like destiny. It’s my absolute pleasure to give Christine a bit of a boost and to have her on the site. If you want to read the story thus far, her blog archives are over here. But for now, welcome to the site, let’s get on with it. -El

A misty morning

Begin with an instrumental call-and-response in the form of a spine-tingling arpeggio which is met by the same figure repeated an octave higher. Eight seconds in come the vocals, which sound as though a bog witch has put on a frilly dress and gone out to cruise for men. Eventually the song ushers in the chorus, with its soaring invocations of the romantic lead of the sort of 19th century novel for which Cliffs Notes were invented. Let’s begin, then, with the obvious question that would have been on the minds of anyone listening to the #1 single on March 11, 1978: what the fuck are we listening to?

To answer that question, it’s useful to look at what “Wuthering Heights” isn’t. The basic set-up of an unknown 19-year-old artist’s debut single based on a classic novel hitting #1 screams “novelty song.” (David Bowie, of course, became known with a novelty single influenced by sci-fi literature and cinema.) Yet “Wuthering Heights” lacks a key ingredient of the novelty format: calculated cynicism that preys on its audience’s liability to fall for a shtick. Bush lacks this predatory instinct. She’s fluent in populist language, but for her pleasing the market is a subordinate priority to using its tropes in the order of making new kings of music.

Tom Ewing has identified the particular strain of populism in “Wuthering Heights”: “[it’s] a power ballad… it also has an absolutely steely conviction in its own seriousness and worth; it stares down even the merest notion that it might be ridiculous.” One suspects this sort of familiarity helped land “Wuthering Heights” on the charts. For all that Bush aims at and successfully hits on “music people haven’t heard before,” there’s an intelligence and understanding of pop language to “Wuthering Heights” that keeps it anchored in the sensibilities of 1978.

I Wish I Were a Girl Again

A frequently remarked-upon aspect of this insight is Bush’s age. She recorded and released this song at 19. The Beatles were singing “Love Me Do” at that age. It’s easier to create bold work like this earlier in one’s career. Bush wrote the song at the age of 18 in March of 1977 (likely March 5th), playing into multiple synchronicities. She shared a July 30th birthday with Wuthering Heights author Emily Brontë, both creators were sick while writing their versions of “Wuthering” (Bush with a cold and Brontë with tuberculosis), and of course the singer’s shared name with two of the novel’s characters (though only one of whom is pertinent to Bush’s song). While the last fact can be chalked down to Bush identifying with a story bearing her name, the former two are eerie coincidences. It’s like history is positioning itself around Bush, ready to be harnessed for her own ends.

“Love Me Do” at that age. It’s easier to create bold work like this earlier in one’s career. Bush wrote the song at the age of 18 in March of 1977 (likely March 5th), playing into multiple synchronicities. She shared a July 30th birthday with Wuthering Heights author Emily Brontë, both creators were sick while writing their versions of “Wuthering” (Bush with a cold and Brontë with tuberculosis), and of course the singer’s shared name with two of the novel’s characters (though only one of whom is pertinent to Bush’s song). While the last fact can be chalked down to Bush identifying with a story bearing her name, the former two are eerie coincidences. It’s like history is positioning itself around Bush, ready to be harnessed for her own ends.

Hence there’s a controlled tempest weirdness to the song. “Out on the wiley windy moors we’d roll and fall in green” is one of the strangest opening lyrics to a pop song ever, turned even odder by Bush’s otherworldly vocal. She sings in a high register throughout the whole track. These trademark high-pitched vocals has turned many stomachs, even among Bush fans (Suede’s Brett Anderson has foolishly dismissed Bush’s early albums as attempts to find her feet). John Peel famously declared he couldn’t take Bush’s high-pitched vocals seriously. Surely the obvious response to this is “yeah, but you thought Rod Stewart was worth taking seriously so shut the fuck up,” but we’d be shooting down. Bush uses the heights of her vocal range to great effect. In “Wuthering Heights,” Bush is a spectre, creeping her way through “bad dreams in the night/they told me I was going to lose the fight.” Her singing is ghostly and demands critical attention from the listener. Yet there’s always a playfulness to her vocals — “I loved you too” is played with a cheeky flirtatiousness. She’s telling a ghost story, but she’s singing an upbeat song. Cathy is a ghost pleading with Heathcliff to let her inside the house. There’s a darkness to the bodily experience here: Cathy is an unsettled soul who can still feel cold beyond the grave. Yet Bush sings her song like she’s a soul coming home after all these years to her love, perhaps to pull him through the window as well. She sings like a siren as well as writing about one.

The cadaverousness of “Wuthering Heights” moves the song into a unique space in 1978 in that it’s gothic but not goth. It’s almost entirely separated from Siouxsie and the Banshees or The Cure, but it’s gothic to its core. The song has a sparkle yet its climate is cold — it’s like the windy moors it conjures. Cathy is the ghost haunting the song, and Bush doesn’t find this a source of horror. The gothic in Bush’s music is something to be played with and blown up.

A perfect misanthropist’s heaven

Let’s talk about the track’s source, Emily Brontë’s classic novel Wuthering Heights. Emily Brontë is like Kate Bush in how we rarely get a good sense of what she did behind closed doors. She was famously reclusive, leaving less fodder for biographers than her more prolific  sister Charlotte. Like Bush, Emily wrote Wuthering Heights, her lone novel, at a young age, although not nearly as young as Bush was (Brontë was well into her twenties when the book was published, shortly before her death at 30.) Death surrounds Wuthering Heights; its mysterious author leaves the book behind as a final statement makes the book even more ripe for interrogation by Bush.

sister Charlotte. Like Bush, Emily wrote Wuthering Heights, her lone novel, at a young age, although not nearly as young as Bush was (Brontë was well into her twenties when the book was published, shortly before her death at 30.) Death surrounds Wuthering Heights; its mysterious author leaves the book behind as a final statement makes the book even more ripe for interrogation by Bush.

Wuthering Heights’ particular brand of gothic is a more social rather than aesthetic one. Emily Brontë casts the genre in a Northern English mold to make it recognizable to a Yorkshire reader. Wuthering Heights itself is effectively a gothic castle in the guise of a northern manor, home to a veritable army of screwed up human beings. The book is populated by incestuous doppelgangers: characters intermarry and give each their children family members’ names (there are two Catherines and Lintons each). This story of a catastrophically dysfunctional family unfolds across 300 pages, eventually leading back to its opening framing device, where Heathcliff dies after a lonely and miserable life desperate for Catherine.

This isn’t an obvious premise for a power ballad. In addition to the story’s lurid hopelessness, the cast of Wuthering Heights is downright horrid. The characters, Heathcliff and Catherine included, subject each other to abuse throughout the book (“you had a temper like my jealousy/too hot, too greedy”), and there’s not much redemption in store for any of them. Whether the book realizes that its entire cast is repulsive is up for debate —Emily’s sister Charlotte seems to find Heathcliff the chief offender in her preface to the book (why yes, Heathcliff is a person of color). The book is fascinating in how far it takes its pathologies. The characters are effectively damned, and there’s no sugar placed on this, with Catherine having “lost [her] way on the moor” long after her death.

To her credit, Bush is immune to any notion of Wuthering Heights being a love story. Indeed, she delights in telling a story about someone like Catherine. “…She’s a really vile person, she’s just so headstrong and passionate and… crazy, you know? And it was fun to do,” Bush said in 1980. And it’s true: Catherine is a selfish, privileged twerp, far from an ideal romantic heroine (although notably, the rest of the characters aren’t much worse). Any Hollywood makeovers given to her aren’t present in the book. She’s there vices and all.

Terror made me cruel

Bush, however, wasn’t introduced to this story by Hollywood. She discovered Wuthering Heights in 1967 when the BBC aired its adaptation of it with Ian McShane and Angela Scoular. The serial is nothing spectacular — there’s a reason it’s not acclaimed alongside I Claudius or Jonathan Miller and Shaun Sutton-eras BBC Shakespeare, and it’s not just Ian McShane in offensive brownface. There’s an odd slavishness to its adaptation of the book that sacrifices the story’s strangeness along the way. Yet it has one truly classic scene that changed the face of British music. Near the end of the serial comes the window scene the song adapts, in which Heathcliff’s unwanted tenant Lockwood is terrified to find the ghost of Cathy reaching through his window, begging to be let in. It’s a genuinely creepy scene that transcends its low budget and low-quality black-and-white video tape by embracing them (BBC drama has always been at its best when it worked with its limits). And at East Wickham Farm on the 18th of November 1967, this cheap BBC costume drama scared the living daylights out of a 9-year-old Cathy Bush.

Jonathan Miller and Shaun Sutton-eras BBC Shakespeare, and it’s not just Ian McShane in offensive brownface. There’s an odd slavishness to its adaptation of the book that sacrifices the story’s strangeness along the way. Yet it has one truly classic scene that changed the face of British music. Near the end of the serial comes the window scene the song adapts, in which Heathcliff’s unwanted tenant Lockwood is terrified to find the ghost of Cathy reaching through his window, begging to be let in. It’s a genuinely creepy scene that transcends its low budget and low-quality black-and-white video tape by embracing them (BBC drama has always been at its best when it worked with its limits). And at East Wickham Farm on the 18th of November 1967, this cheap BBC costume drama scared the living daylights out of a 9-year-old Cathy Bush.

One feels this scene never left Bush alone. When an adaptation (presumably the 1939 William Wyler film) aired on TV she furiously channel-flipped until she caught the last ten minutes of it. When she read the book in 1977, a Kate Bush song about Wuthering Heights was inevitable. The manor’s ability to haunt reached beyond the pages of the book — its power went into creating other versions of itself.

One of the ways in which Wuthering Heights fits into the 19th century literary gothic tradition is the roles it places its characters in. Heathcliff is the broken man discovered at the beginning of the book before his story is related to a narrator and the monster he hides is revealed (see Frankenstein for another example). This is straightforward enough. The monster he hides is Cathy’s ghost. This is a particularly poignant and social monster due to her literal humanity, one whose needs have continued beyond the grave.

Bush’s “Wuthering Heights” is in effect reanimating a corpse, but more importantly she’s giving agency to a gothic monster. Her Cathy is adamant in how she just won’t die. She insists on living beyond the grave in order to achieve her desires. To Brontë this is fodder for a creepy ghost story. With Bush, it’s a homecoming. After all these years lost on the moors, Cathy is “coming home to Wuthering, Wuthering, Wuthering Heights.” Her tone is not fear but jubilation. To the ghost, coming home is returning to where she ought to be.

There’s a radical dimension to this: the song is addressed to Heathcliff, but he exists entirely offstage. He is the object of Bush’s gaze. The gothic antihero is not the point of Bush’s song. He’s a reward, not the point of the song. It’s Cathy’s satisfaction that matters in this version of the story.

To sparkle and dance in a glorious jubilee

I’ve often argued in Dreams of Orgonon that Bush’s most frequently utilized narrative strategy is uprooting a character from a preexisting story and giving them interiority. In “Wuthering Heights” Bush does something a bit different — she takes the original story and changes its tone. The lines “let me in” and “I’m come home: I’d lost my way on the moor!” are present in the novel but the cries of a lost soul. When Kate Bush sings them, she’s giddily knocking on the window, demanding to be admitted into “Wuthering Heights.” There’s a sense the book anticipated Kate Bush. With the synchronicities of the book and song’s creations, it’s hard not to think so. Bush’s “Wuthering Heights” is an answer to Brontë’s “Wuthering Heights,” and thus imposes itself on the book’s legacy.

This aesthetic revisionism is everything The Kick Inside stands for. The album’s preoccupations with expression, bodily liberty, and new ways to be a woman in the latter days of the Seventies are all present in the song. Bush latches onto Cathy’s need to desire (“how could you leave me/when I needed to possess you/I hated you/I loved you too”). A crucial part of liberty is the freedom to desire and pine.

In accordance with this liberty, Bush carries off “Wuthering Heights” with such ease. Her singing is offbeat and non-conventional but blatantly  works. She phrases her lyrics with dramatic pauses and breaks in odd gaps. Her emphasis on “you had a temper” followed by the rapid concession of “like my jealousy” is terribly in character for Cathy. She knows how to be coy and how to express fear (“turn down that road in the night” sounds genuinely panicked, as if she’s ready to lunge headfirst through Heathcliff’s window.) These turns would sound jarring from any other singer (covers struggle with the song’s tonal shifts), but Bush anchors it all with a mercurial gravity that takes the material dead seriously. Who else would handle placing the first syllable of “Heathcliff” in the pre-chorus and using the second to land the chorus this well?

works. She phrases her lyrics with dramatic pauses and breaks in odd gaps. Her emphasis on “you had a temper” followed by the rapid concession of “like my jealousy” is terribly in character for Cathy. She knows how to be coy and how to express fear (“turn down that road in the night” sounds genuinely panicked, as if she’s ready to lunge headfirst through Heathcliff’s window.) These turns would sound jarring from any other singer (covers struggle with the song’s tonal shifts), but Bush anchors it all with a mercurial gravity that takes the material dead seriously. Who else would handle placing the first syllable of “Heathcliff” in the pre-chorus and using the second to land the chorus this well?

Bush has total command of the song’s melody. “Wuthering Heights” has a concise structure of intro/verse/pre-chorus/chorus/verse/pre-chorus/chorus/bridge/chorus/outro which keeps the song moving and indulges in its pleasures without overstaying its welcome. The song appears to begin in A major but quickly reveals itself to be in F sharp minor, a conspicuous choice of key change signaled by the two keys’ use of three sharps, creating a fascinating mix of tension and uplift. As Cathy experiences her “bad dreams in the night,” the song creeps into B flat minor, before explosively modulating into D flat major for the chorus. While these key changes dazzle, the time signature is just as malleable. The first verse moves forward in 4/4 while the pre-chorus dips into 2/4, before the chorus pulls a series of time signature shifts from 4/4 (“it’s me, Cathy”) to 3/4 (“I’m so cold”) down to 2/4 (“let me in-a your window”) before settling on 3/4 for “window.” The second verse then slows down to 2/4, the time signature of the pre-chorus which is retained for the bridge. The chorus repeats and the outro carries on in 4/4, led by Iain Bairnson’s legendary guitar solo. There’s not a bum note in “Wuthering Heights.” As a song, it’s a masterpiece.

And one can’t imagine a more fitting visual rendering of “Wuthering Heights” than the music videos produced for it. The first video directed by Nick Abson filmed on location at Salisbury Plain is probably more iconic as it’s the more literal video. Bush’s red dress and the use of an actual moor has to many people become the definitive image for Wuthering Heights as well as “Wuthering Heights.” The second video shot by Bush mainstay Keef Macmillan is perhaps more in tune with the atmosphere of the song, with its black room and echo-visual-effect placed on a glowing Bush, but it’s stodgier and less satisfying. But perhaps even more iconic than either video is the dance. Bush had been learning dance from legendary mime Lindsay Kemp for a time, and it shows. Bush’s choreography is less classical and more representative — she’s intent on capturing a character. “When I needed to possess you” is expressed poignantly by early Bush’s signature glance directly into the camera, while she directly holds her hands out for the pre-chorus. The precise spinning of “Heathcliff, it’s me, Cathy” is, of course, the highlight, right next to the farewell wave of the outro. “Wuthering Heights” is not only sung but danced.

The solitary neighbour

The spectacle of a 19-year-old auteur pulling this off was astonishing to record label EMI. Indeed it seems like they didn’t realize they had a hit on their hands. Executive Bob Mercer wanted “James and the Cold Gun” for lead single on The Kick Inside, but Bush was tearfully resolute on making “Wuthering Heights” her thesis statement. She got her wish, and handled the market better than the experts did. EMI did, however, make the wise decision to not bill their new star right before Christmas (and rightfully so — Paul McCartney and Wings were hijacking the charts with “Mull of Kintyre,” the bestselling single in UK history at that time). Unfortunately for EMI (or perhaps rather fortunately), copies of the single had been sent out prior to the delay, and radio stations loved “Wuthering Heights” enough to play it prior to its release. The ghost was making its way into audience’s ears.

And then it exploded. “Wuthering Heights” debuted on the 20th of January 1978, lingering for a month before moving comfortably into the Top 40 on the 14th of February. Two days later Bush was on Top of the Pops, making an unprepared performance of the song and looking appropriately ready for death. But the appearance caught enough people’s attention that by the 21st “Wuthering Heights” was at #13 on the charts. As Bush got more press attention and did scads of interviews, the song rose to #5 on the 28th. On the 2nd of March, the Macmillan video was showed on Top of the Pops and insured that “Wuthering Heights” wasn’t going away. Finally, on the 7th of March, Kate Bush’s debut single, recorded and released when she was 19, topped the charts, less than two months after its release. EMI were appropriately gracious, holding a champagne reception for Bush and giving her dinner in Paris. To celebrate, Bush used some of her royalties to buy a £7000 Steinway piano. Her success made her confident she wouldn’t stop there.

And she didn’t. The Kick Inside peaked on the albums charts at #3. In the same year, Bush would release her second album and begin planning her one and only concert tour. This was the most promising start to a career Bush could have asked for, and she wasn’t one to look a gift horse in the mouth. In 1986, she cut a new vocal for the song to appear as the opening track of her compilation The Whole Story. Yet the story of “Wuthering Heights” had a life beyond that.

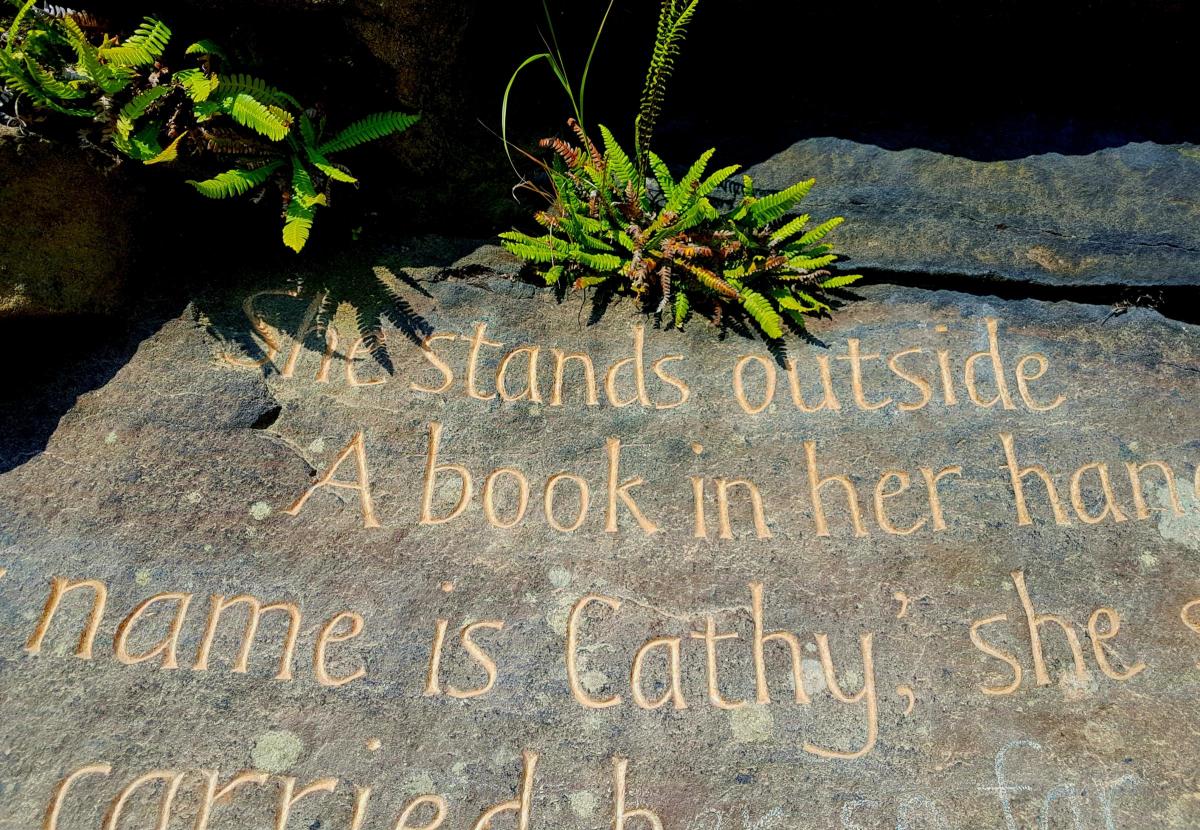

In 2018, Kate Bush made a rare public appearance to pay tribute to her old muse, Emily Brontë. As part of the Bradford Literature Festival, Bush was one of numerous writers to write a poem set in stone in Brontë’s honor:

She stands outside

A book in her hands

“Her name is Cathy,” she says

“I have carried her so far, so far

Along the unmarked road from our graves

I cannot reach this window

Open it, I pray.”

But his window is a door to a lonely world

That longs to play.

Ah, Emily. Come in, come in and stay.”

Perhaps the years has shifted Kate Bush’s perspective on Cathy and Heathcliff. But her respect for Emily Brontë and her creation has never gone. “Cathy will live on as a force. I was lucky she stopped in me long enough to write a song,” Bush mused in a 1980 book of sheet music. The ghost of Cathy hasn’t stopped haunting Kate Bush. She gave Bush a career. And Bush hasn’t left us alone either. May she haunt us for years to come.

Recorded between July and August of 1977 at London AIR Studios. Released as a single on 20 January 1978 and then on The Kick Inside 17 February 1978. Personnel: Kate Bush — vocals, piano. Stuart Elliott — drums. Andrew Powell — bass, celeste, production. David Paton — acoustic guitars. Iain Bairnson — electric guitar. Duncan Mackay — organ. Morris Pert — percussion.

January 18, 2019 @ 10:32 am

Fascinating read! I’ve studied Bronte’s “Wuthering Heights” a couple of times in respectively different circumstances, and it’s interesting the extent to which it seems to haunt Bush (and, indeed, how Bush responds to Bronte through this song). The red dress video tho is incredibly capital-R Romantic

January 18, 2019 @ 12:09 pm

Wow, this is much better than the usual guy.

January 18, 2019 @ 5:21 pm

The other guy’s problem is he doesn’t write much about Kate Bush.

January 24, 2019 @ 5:26 am

Hard agree.

January 18, 2019 @ 2:31 pm

Loved this, thought it was a great read. I’ve been meaning to listen to more of Kate Bush and this project may be what I need. I saw “Kate Bush at the BBC” over christmas and I loved it, such a charasmatic performer coupled with lyrical images no-one else can match. I found her genuinely enthralling.

January 18, 2019 @ 3:05 pm

This takes me back. A long way.

The second video for the song was how I encountered it in the opening weeks of MTV, where the main requirement for airplay was “existing.” This meant that Juice Newton went beside of Iron Maiden and beside of Kim Carnes and beside of roughly 20 videos by Rod Stewart, and, yes, this sublimely weird song about a book I knew my sister had read. I had no idea until a long time later that it was a massive hit in England, so it was just an oddity, a curiosity.

(In keeping with the Doctor Who theme around these parts, I had moved the previous year, from an area that played Doctor Who on PBS to an area that didn’t play it, and I didn’t see Doctor Who on TV again until the summer of 1983. Doctor Who had been reduced to a book from the Science Fiction Book Club that was an omnibus of the novelizations of Genesis of the Daleks, Revenge of the Cybermen, and Terror of the Zygons. Were I to write about Doctor Who, most of it would be writing about the gaps in time where the show haunted me until 2005.)

And, I have to admit it, I didn’t like the song. I was fourteen years old and was falling into the world of heavy metal, so Kate Bush was kind of surplus to requirements. But it clearly stood out to me, because it’s one of the few songs of the early MTV era from artists I didn’t like that I still remember to this day, where a lot of early MTV has drifted far from mind.

Except for all those damn Rod Stewart videos. He must’ve made a LOT of them.

January 18, 2019 @ 6:32 pm

congrats on the new venue!

January 18, 2019 @ 10:36 pm

Welcome aboard, Christine! That was a marvelous read; you’ll fit in here nicely. In general, except for her extraordinary ‘the Dreaming’/ ‘Hounds of Love’, Kate Bush’s music is more something I admire/ like-well-enough than love. It looks like you’ll be doing your best to fix that, and I hope you do.

January 19, 2019 @ 6:52 am

God he looks like Rufus Sewell in that pic.

January 20, 2019 @ 2:18 am

Very much enjoyed this essay. I’ve been through distinct phases in appreciation of Kate Bush (somewhat disturbed by the recent ‘Tory’ wobble in which I made the same glib assumption as so many), but after her pop mastery around the Hounds of Love, I found myself really loving the confident sensuality of The Sensual World and The Red Shoes (especially the title track of the former, and Lily, on the latter). These, of course, came straight after The Whole Story, so I’m curious what you make of her revised take on the vocals of Wuthering Heights?

From a purely musical point of view, Kate’s mature vocals are easier on the ear and more sophisticated, but do you think they lose the intensity? My wife doesn’t like Kate Bush much (especially earlier songs), and complains that she sounds dangerously insane. I wonder if this sense of being on the edge is more prevalent in the earlier version?

January 20, 2019 @ 4:48 am

The new vocal has its high points – I love Bush losing her shit towards the end. But generally I think it’s a pointless redux done mostly to satisfy Bush’s perfectionism.

January 21, 2019 @ 10:21 am

I agree with you. I put it in the ‘Keith Richards doing a version of Satisfaction with the saxophone his fuzz guitar was original a placeholder for’ category. An affectation by an artist a little too close to the work to recognise that ‘flaws’ can be an essential part of a work’s appeal.

January 20, 2019 @ 7:56 pm

I’ve never had much of an interest in Kate Bush, however, I found that I largely enjoyed your essay. Also, having just searched ‘Orgonon,’ I’m intrigued and look forward to your entry on that!

January 22, 2019 @ 10:31 am

Thanks for this. It’s a great essay about a song I don’t think I’ve heard before. I look forward to discovering other KB songs with your essays.

January 22, 2019 @ 1:57 pm

This is one of perhaps three Kate Bush songs I actually know, but nevertheless I found the essay no less than wonderful. I especially enjoyed the focus on haunting, on ghosts that are able to move freely between fiction and reality. I am very much looking forward to reading more of your writing.