Fascistic Beasts and Why You Shouldn’t Fight Them

SPOILERS / TRIGGERS

SPOILERS / TRIGGERS

I’m going to generally assume you’ve seen this film and the previous one.

*

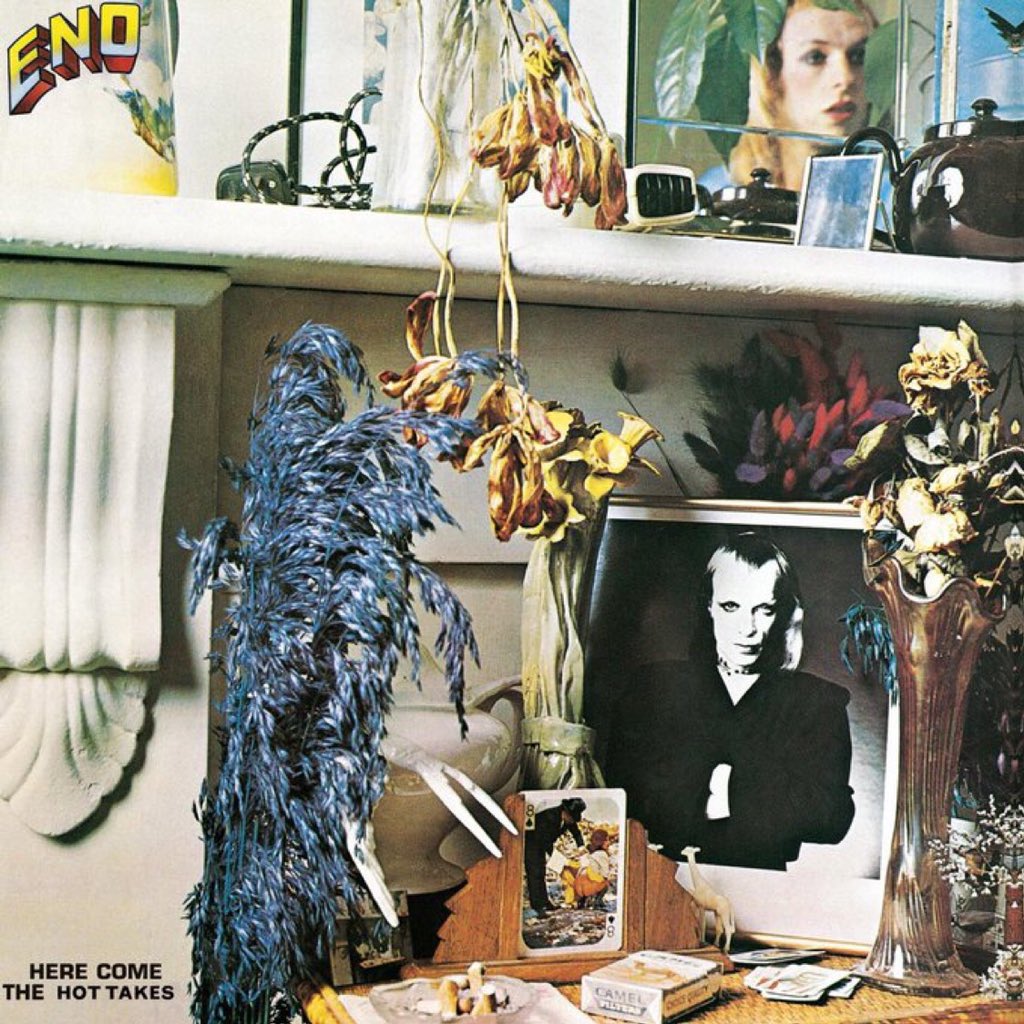

It is entirely apt that the poster for The Crimes of Grindelwald features a crowd of people wandering about looking confused; it’s both an apt depiction of the film and of the audience on their way out of the cinema.

An even better encapsulation: the sinking of the Titanic features, briefly, as a throwaway and perfunctory period reference, in a flashback scene in the middle of an infodump, part of the resolution of a pointless subplot… and nobody asks why the wizards on board didn’t stop it sinking.

Bluntly, this film is a mess. The plot flaps around, bifurcating into dead end after dead end. Things are set up and not paid off. When the payoffs do arrive they are sudden, arbitrary, and unsatisfying. There are lots of events but nothing really happens. Nothing is achieved. Every time you think progress might be made you find yourself stuck in a new subplot surrounded by characters who are multiplying around you like those cursed goblets in the final Potter film.

The first Fantastic Beasts movie had a more than incipient case of this, with the subplot about a plutocrat Jon Voight and his two sons, on top of the subplot about witch-hunters, and the plot about Grindelwald in disguise hunting a powerful cursed child… all on top of the stuff about Newt getting entangled with new friends and local magical authorities in 20s New York while trying to recapture the magical creatures that escaped from his case. This last would’ve made a perfectly entertaining little movie all by itself.

The main attraction of the first film – the likeable main characters; played by a uniformly charming cast – is squandered. The core cast do their best but they get very little time together, and even less in which they can have fun. The mood is dour compared to the first film. These stories about people with magic wands who conjure bats made of bogeys at each other are getting Dark and Serious again.

The colour pallette has been drained correspondingly. The first film allowed us a bit of sunlit sepia in 20s New York; this gives us 20s Paris almost in monochrome. Just as everyone is starting to snap out of that trend for washed-out colours and oppressive shadows, David Yates is digging his heels in and making Wizarding World movies the same murky way he shot Half-Blood Prince. Some of the production design is nice, especially the art nouveau interior of the French Ministry of Magic – even if it’s always a bit too evident in advance which era cliches the production designers will give a perfunctory magic twist.

But the overall grey uniformity of the film – also mirrored in the poster – is fitting for such a lifeless experience. A lot of effort is expended seemingly just to get new characters in place ready for future installments. They’ve tried to cram lots of set-up for the next movies into this film, almost as if they realised they came perilously close to telling a self-contained tale last time.…

Join El and Annie Fish

Join El and Annie Fish  As noted last time, through its strategy – deliberate or not – of eloquent silence, ‘Demons of the Punjab’

As noted last time, through its strategy – deliberate or not – of eloquent silence, ‘Demons of the Punjab’

The historian Yasmin Khan, who wrote

The historian Yasmin Khan, who wrote