Guest Post: Alternate Histories, Part 2b: I Still Have No Idea What I’m Talking About

Here’s Part 2 (well, part “2b”) of Ben Knaak’s Alternate Histories project exploring how to model a materialist conception of history through video games. Be sure to follow along on his blog and YouTube Channel!

Shit I Don’t Know, Entry #2: Who’s Playing This Game?

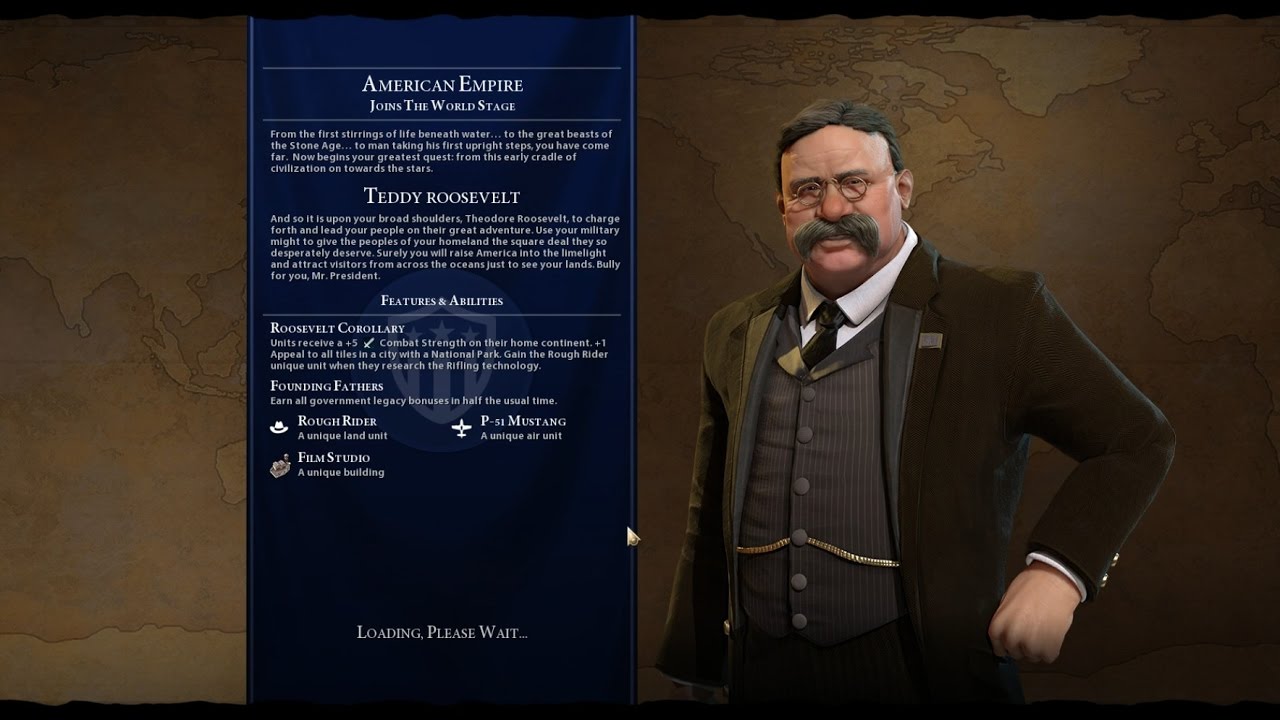

In most 4X games in which the player controls a nation, that nation’s identity, attributes, and associated play style remain static and constant. Rather than a contingent cultural and political reality that arises from particular circumstances, the nation is an eternal reality. It will often have a set of statistical bonuses or accompanying debuffs, or a unique unit or building it can construct once the correct technology has been researched, simply by virtue of being itself. The nation exists at the beginning of the game, and barring conquest by another nation it will exist at the end. Every player who chooses “America” begins history with the founding of Washington in the year 4000 B.C. Where did these people come from? Are they white? Patawomeck? Who is this Washington they named their settlement after? It’s not important; welcome to the United Neolithic States.

This works fine for a Civilization game, but for grand strategy, it just won’t do. And it especially won’t do for a game like Victoria II, which attempts to draw from a more sophisticated, materialist version of Video Game History™. This is a game in which the names, flags, and borders of its states must necessarily change with astonishing regularity, and in ways that are historically contingent without being pre-ordained. Prussia, or perhaps Austria, becomes Germany. Sardinia-Piedmont, or perhaps the Two Sicilies, or perhaps the Papal States, becomes Italy. Or perhaps neither of those states comes into being. New countries are carved from the carcasses of moribund empires, imposed from without and from within.

What, then, are the in-game forces that govern these processes? As you would expect, nationalist movements are partially determined by the POP system. Every POP group has an associated culture group. In Ethiopia, for instance, one might have a POP group of Oromo craftsmen working with a group of Tigrayan clerks in a factory owned by Amhara capitalists. Each country, in turn, has at least one culture designated as its primary culture, and may have one or more accepted cultures. Status in one of these groups has a significant effect on POPs’ beliefs and behaviors. Primary culture POPs are more likely to support residency for non-primary culture POPs, while accepted culture POPs are more likely to support limited citizenship (which, for instance, allows accepted culture POPs to vote if your country allows elections). Primary culture POPs are also much more likely to promote to capitalists and other upper-class strata. Non-accepted POPs with high literacy, good living conditions, and few reasons to complain will tend to assimilate to an accepted culture, unless there exists a nation with their culture as its primary culture which holds cores on that province. Meanwhile, literate, high-consciousness POPs of a non-accepted culture are likely to see their militancy increase if their rights are not granted.…

Sections of this piece are drawn from conversations with

Sections of this piece are drawn from conversations with

The earliest known state to emerge was the Kingdom of D’mt around the 10th century BCE. The people of this kingdom spoke an early Ethio-Semitic language, and traded extensively with the Sabeans of the Southern Arabian peninsula. (They were almost certainly not descended from Sabean migrants themselves – Ethiopia was, in fact, one of the first places Semitic languages were spoken). This kingdom gave way to (or evolved into, or was incorporated into) the Kingdom of Axum, a prosperous superpower whose extent at its apex reached across the Red Sea into Yemen. Notably, it was among the first states to adopt Christianity as an official religion. Axum collapsed under mysterious circumstances in the 10th century CE, even as the heart of its territory remained predominantly Christian. This was succeeded by the Ethiopian Empire, ruled first by the Zagwe dynasty and then by the Solomonic dynasty – so named because it claimed descent from the first King of Axum, whom they claimed was the son of King Solomon by the Queen of Sheba.

The earliest known state to emerge was the Kingdom of D’mt around the 10th century BCE. The people of this kingdom spoke an early Ethio-Semitic language, and traded extensively with the Sabeans of the Southern Arabian peninsula. (They were almost certainly not descended from Sabean migrants themselves – Ethiopia was, in fact, one of the first places Semitic languages were spoken). This kingdom gave way to (or evolved into, or was incorporated into) the Kingdom of Axum, a prosperous superpower whose extent at its apex reached across the Red Sea into Yemen. Notably, it was among the first states to adopt Christianity as an official religion. Axum collapsed under mysterious circumstances in the 10th century CE, even as the heart of its territory remained predominantly Christian. This was succeeded by the Ethiopian Empire, ruled first by the Zagwe dynasty and then by the Solomonic dynasty – so named because it claimed descent from the first King of Axum, whom they claimed was the son of King Solomon by the Queen of Sheba. Dismembered Bits and Pieces of an Introduction;

Dismembered Bits and Pieces of an Introduction;