Guest Post: Alternate Histories Part 2a: I Have No Idea What I’m Talking About

Here’s Part 2 (well, part “2a”) of Ben Knaak’s Alternate Histories project exploring how to model a materialist conception of history through video games. Be sure to follow along on his blog and YouTube Channel!

Shit I Don’t Know Entry #1: Where Are We?

Here I must confess as to the greatest difficulty I face with a project that deals extensively with Ethiopian history: if you held a gun to my head, I would not be able to give you a concise, coherent definition of what Ethiopia even is. The concept of the nation in general is a nebulous one that at even its most vivid doesn’t come close to approaching a science. National consciousness is therefore one which a historical materialist must regard with healthy skepticism, even when it accompanies a struggle for liberation against colonizers. It certainly isn’t a sufficiently robust concept to be the sole basis for the authority of a state.

You will note that I have elected not to take the coward’s way out by appealing to a dictionary definition of the word “nation.” There are two reasons for this: first, it’s a hacky, middle school essay-ass way to start off an article. Second, I can’t find a single definition of the word that cannot be disputed for some ideological reason or another. Most center around the existence of linguistic, religious, cultural, or other historical commonalities by peoples within a contiguous area, but bright-line requirements that separate nations from mere states are hard to come by. This is perhaps something I ought to have considered before I decided to make nationalism the second topic for this series, because Ethiopia’s history as a nation is a messy subject even by these standards.

There have, of course, been humans in Ethiopia for nearly as long as there have been humans, with the arrival of Homo sapiens proper dated to over 200,000 years ago. Most of the population of the Horn of Africa today descend from toolmaking cultures who lived around 12,000 years ago. These people likely spoke a proto-Afroasiatic language and indeed may have been the progenitors of that entire language family.

The earliest known state to emerge was the Kingdom of D’mt around the 10th century BCE. The people of this kingdom spoke an early Ethio-Semitic language, and traded extensively with the Sabeans of the Southern Arabian peninsula. (They were almost certainly not descended from Sabean migrants themselves – Ethiopia was, in fact, one of the first places Semitic languages were spoken). This kingdom gave way to (or evolved into, or was incorporated into) the Kingdom of Axum, a prosperous superpower whose extent at its apex reached across the Red Sea into Yemen. Notably, it was among the first states to adopt Christianity as an official religion. Axum collapsed under mysterious circumstances in the 10th century CE, even as the heart of its territory remained predominantly Christian. This was succeeded by the Ethiopian Empire, ruled first by the Zagwe dynasty and then by the Solomonic dynasty – so named because it claimed descent from the first King of Axum, whom they claimed was the son of King Solomon by the Queen of Sheba. Though the legend predates its writing, the main basis for this claim is found in the medieval Kebre Negast – a national literary epic similar to the Arthurian romances both in terms of its cultural importance and its reputation for historical accuracy.

The earliest known state to emerge was the Kingdom of D’mt around the 10th century BCE. The people of this kingdom spoke an early Ethio-Semitic language, and traded extensively with the Sabeans of the Southern Arabian peninsula. (They were almost certainly not descended from Sabean migrants themselves – Ethiopia was, in fact, one of the first places Semitic languages were spoken). This kingdom gave way to (or evolved into, or was incorporated into) the Kingdom of Axum, a prosperous superpower whose extent at its apex reached across the Red Sea into Yemen. Notably, it was among the first states to adopt Christianity as an official religion. Axum collapsed under mysterious circumstances in the 10th century CE, even as the heart of its territory remained predominantly Christian. This was succeeded by the Ethiopian Empire, ruled first by the Zagwe dynasty and then by the Solomonic dynasty – so named because it claimed descent from the first King of Axum, whom they claimed was the son of King Solomon by the Queen of Sheba. Though the legend predates its writing, the main basis for this claim is found in the medieval Kebre Negast – a national literary epic similar to the Arthurian romances both in terms of its cultural importance and its reputation for historical accuracy.

It is in this medieval period that a cultural and linguistic transformation began to emerge. Ge’ez remained the liturgical and literary language of the priests, chroniclers, and poets. In the north, the Tigrinya language developed. But as the political center shifted southward, Amharic, a new language which had acquired lexical and grammatical traits from the Cushitic and Omotic speakers who also lived and traded in the highlands, became a lingua franca. Under rulers such as Zara Yaqob, Ethiopia flourished, prospering from trade and protecting itself from aggressive neighbors. But the region was subsequently thrown into chaos when the Sultanate of Adal invaded Ethiopia, armed with imported Turkish cannons. Ethiopia itself appealed for aid, and the conflict turned into a long, bloody proxy war between the Turks and the Portuguese for dominion over the Red Sea. In the end, Ethiopia prevailed, but both states were left severely weakened.

This led to the next great influx of people into the Ethiopian state – the Oromo migrations. Spurred by raids against them from the Abyssinian highlands, as well as the desire for better land for herds and grain, they took advantage of the weakening of the Ethiopian state and collapse of Adal to move north into the highlands, at spearpoint when necessary. At the time of the migration, they followed their traditional religious beliefs and way of life, governing themselves through a complex and robust form of democracy called gadaa. Over the next several centuries, their society transformed in proximity to their new neighbors, as some Oromo leaders proclaimed kingdoms or even married into the imperial family. This transformation occurred through peaceful and gradual integration in some places and times (mostly in the north), and brutal subjugation in others (particularly in the south during the bloody campaigns of Menelik II).

The Empire remained whole, albeit weakened, until 1769, when Ras Mikael Sehul deposed Emperor Iyoas. He lacked both the bloodline and the desire to claim the throne for himself, so he installed a puppet in Iyasu II and ruled instead as regent. This would remain the typical state of affairs during the period of political fragmentation that would come to be known as the Zemene Mesafint – the Era of the Princes. Though a Negusa Negast would continue to reign in name, Ethiopia was in practice divided into more-or-less independent princedoms whose most powerful rulers would fight to place Solomonic puppets of their own on the throne. The conflicts of this era at times acquired the dimensions of religious conflict between Christians and Muslims, at other times ethnic conflict between the Amhara, Tigrayans, and Oromo, and at other times feudal squabbling over which the people in general were indifferent (or indeed, some combination of all or none of the three). It was in certain phases regarded by the people as a local Gondarine affair and at other times a national calamity, the subject of millenarian warnings by itinerant preachers. It is said that in the 1830s a prophecy popular among the Christian peasantry predicted that peace would be restored to the land by a great emperor who would take the name Tewodros, after a short-lived emperor who was in legend a defender of the poor.

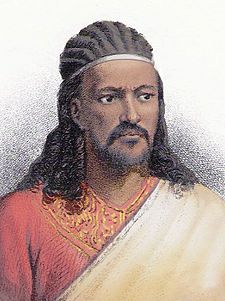

This may have been on the mind of the upstart Ras Kassa Hailu when he made his bid for the throne. When he defeated the last of the warlords in 1855 (or 1841, in certain timelines), he was proclaimed Negusa Negast and chose Tewodros II as his throne name. But though he ended the Era of Princes, he would not bring peace. His ambitious centralization policies alienated the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and with it the peasantry from which he drew so much of his support. As his reign dragged on, he became prone to violent outbursts. He would commit suicide as an invading British army approached, by the end controlling little of the country outside his own castle (thus beginning a long history of British imperial hostility to Ethiopia’s existence). The Zemene Mesafint did not reassert itself, however – instead, Emperor Yohannes IV would take his place through the strength of foreign firearms.

Yohannes’s rule permitted significantly more autonomy for the local nobles of his realm than his predecessors, demanding only their loyalty. This was beneficial for the stability of the Empire, but had the consequence of permitting Menelik, the King of Shewa, to consolidate his power in the hopes that he might some day usurp the throne. The Egyptians intended to take advantage of this rift when they launched their invasion in 1875, seeking to bring the whole of the Nile under the rule of the Khedive. But they incurred Menelik’s ire when they occupied Harar, which the Emperor and King both regarded as rightful Ethiopian territory. When Egypt’s well-equipped, Western-supported army marched southward, the Ethiopians inflicted two sound defeats upon them.

It is around the twenty years that followed these victories that the question of Ethiopia as a nation turns.

Not long after Ethiopia’s victory, the Khedivate of Egypt faced a major crisis, as the Mahdi Rebellion drove the entire Egyptian Army out of all of Sudan except for a beleaguered garrison at Suakin. Yohannes signed an agreement with Britain and Egypt in which the Khedivate’s troops were permitted to withdraw through Ethiopian territory in exchange for access to the Red Sea port of Massawa. In the Middle Ages, this region, corresponding roughly to modern-day Eritrea, had alternately been directly ruled by, a vassal of, or independent of the Ethiopian Empire. After the war with Adal, however, it had fallen under Turkish control. In fact, Britain had no intention of honoring their agreement with Yohannes, later tacitly agreeing to grant the city and its environs to the Italians.

When Yohannes died in battle against the Mahdists in 1889, Ethiopia was thrown into a succession crisis between Menelik and Yohannes’s bastard son Mengesha, and Italy was poised to take advantage. They hoped to create either a civil war or a willing client kingdom. In the end it was Menelik who came to an agreement with them, signing the Treaty of Wuchale, in which Menelik agreed to recognize Italy’s claim to Eritrea in exchange for promises of weapons and economic aid.

However, there were two different versions of the treaty. One was written in Amharic and contained only those provisions already described. The other was written in Italian, and effectively established Ethiopia as an Italian protectorate. Menelik would not learn of this until his correspondence with the German kaiser was answered with a rude reply that insisted he could only deal through the King of Italy. To Italy’s surprise, Menelik responded by repudiating the treaty in its entirety. Not comprehending their own arrogance, Italy then attempted to placate him by giving him two million rounds of ammunition. This is generally not remembered as one of history’s greatest decisions.

Nor, indeed, was anything the Italians did subsequently. Expecting, as the Egyptians did, to receive the enthusiastic support of a disgruntled claimant to the throne, they appealed to Ras Mengesha to defect. He flatly refused. Then, through the urging of distant politicians in Rome who demanded a decisive victory over the savage Africans to boost their prestige, General Oreste Baratieri marched his army into battle at Adwa, where his outnumbered (and, astonishingly, outgunned) forces were handed a decisive defeat.

But Menelik could go no further. Ethiopia had already stretched its capacity to supply an army to its limit. Ironically, had Baratieri waited even two days more, the Ethiopians, who were rich in arms but short on food, may have been forced to disperse. Thus the destiny of two states was written: Ethiopia had stood together and would remain independent, but Eritrea would not be part of it. Though Ethiopia and Eritrea would be coupled together in a federation after the Second World War due to American influence (they feared that Italy might form a communist government and put a key Red Sea port in Soviet hands), this union would buckle under the increasing authoritarianism of the Ethiopian government. After a plebiscite in 1993, Eritrea and Ethiopia are now officially recognized as two separate nations.

Some, however, have questioned whether Ethiopia should be considered a nation at all. They argue that it is instead a 19th-century imperial invention whose borders and state apparatus arose from alternating conflict, collaboration, and opportunism between the Solomonic dynasty and the Western imperial powers. There is certainly a coherent case to be made for this. Most of the southern and eastern portions of the country, containing large portions of its Oromo and Somali populations, in particular, were still in the process of being conquered at the time of Menelik’s victory over the Italians at Adwa. In addition to the people slaughtered directly in the invasion itself, many more died of hunger as a result of the rinderpest zoodemic that the Italians had brought with them to Eritrea. Menelik’s invasions exacerbated the effects of this famine, both through direct looting of healthy livestock and by the mass displacement these destructive wars brought about. The slaves and plunder gained from these conquests, which must fairly be called imperialist, were instrumental in funding the army that defended independence at Adwa. What’s more, much of the success of Menelik’s state came from his playing the European powers off of each other. The Russians, who sympathized with Ethiopians as Orthodox Christians and saw them as a bulwark against British expansion in Africa, were crucial partners.

Furthermore, Ethiopia is far from the homogeneous body that most nationalists want to make when they draw their little maps. There are eight officially recognized regional languages in Ethiopia, and dozens more ethnolinguistic groups throughout the country. Though a majority of its citizens are Ethiopian Orthodox Christians, there is also a sizable Muslim minority. Many of these ethnic and religious minorities have suffered greatly from discrimination and violence, particularly under the Derg and in the latter days of Haile Selassie’s reign. Ethiopia is, in short, the successor state to an empire – a monarchial imposition that you could fit a Texas and a half into.

This position, however, is hardly unique, even among nations whose existence is seldom questioned. The formation of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861 was largely the result of political maneuvering by Sardinia-Piedmont, who piggybacked on conflicts between Prussia, Austria, and France to expand their territory. In each case, their armies had little effect on the outcomes of these wars. A robust nationalist movement did exist, largely republican in character, but these movements failed to achieve much on their own. Indeed, many of the central figures in unification did more to fight against the movement than for it. Even as Garibaldi was leading the Expedition of the Thousand to Sicily, the Comte di Cavour, whose kingdom it would help to bring about, was leaking information to the Neapolitans in an effort to undermine him. Above all else, Cavour’s primary aim was to elevate the House of Savoy by any means necessary, no matter which other countries had to fight unrelated conflicts in order to do it, or how many revolutionary countrymen had to die in the process. Were it not for the vascillating support of Louis-Napoleon, the Kingdom of Italy might have come to be much later than it did, or perhaps even not at all.

The Italian state did, of course, have the legacy of Rome to point to, but if they wanted to do that they needed to get in line. Half the great powers of Europe claimed their authority from the Roman Empire in some way or another, from the Habsburgs to the Romanovs to the Ottomans. The historical reality was that a unified, independent state of Italy had not existed in fact since the time of the Lombards, and the ceremonial title within the Holy Roman Empire barely existed even in name by the dawn of the early modern period. The only Kingdom of Italy to exist in living memory was the Napoleonic puppet kingdom, which didn’t even cover the whole peninsula.

Over these long centuries, Italy fragmented into regions with profoundly different cultures and political traditions. At the date of its founding, almost nobody in this new country could speak or read the Florentine prestige dialect we now call Italian, speaking instead one of several mutually unintelligible regional languages. The south was particularly disinclined to assimilate – the inefficiencies of the newly-imposed state and economic apparatuses (particularly land distribution) were instrumental in fueling the rise of the Sicilian Mafia. It was in this climate that the Sardinian aristocrat and statesman Massimo d’Azeglio famously declared that “Italy has been made. Now it remains to make Italians.”

If consistent cultural, political, and lingusitic unity are not requirements for nationhood, then it would seem the barriers to it are quite low. Yet even states which had several of these things have failed (by nationalist logic, they were not, in fact, nations at all). Yugoslavia was the culmination of a sincere Pan-Slavic nationalist movement that seized its moment in the downfall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, reaching an agreement for union with the Kingdom of Serbia. It had more linguistic unity than Italy at its founding, and its religious divisions were not unique – Albania saw similar levels of religious pluralism. But Yugoslav unity was an illusion, and it died a violent death within the span of a human lifetime.

The question of nationhood will always be fraught with difficulty, since like all social constructs its definition changes depending on time and political context. The relationship between Ethiopia’s ethnic groups has historically always been complex (far, FAR too complex to adequately describe here), and their relations with each other have evolved over time. However, they have always related to each other in ways that they do not relate to groups outside the Ethiopian sphere, in ways that include ritual practice, economic adaptation and specialization, and a tendency to unite against common enemies. Indeed, the Ethiopian nation has more of a historical claim to existence than any American settler-state, and at least as strong a claim as most European states. The most spirited defense of Ethiopia as a nation that I have found comes from Professor Harold G. Marcus:

“[F]rom time to time, the nation ha[s] disintegrated into component parts, but it ha[s] never disappeared as an idea and always reappeared in fact. The Axumite Empire may have faded in the seventh century, but the Zagwes followed in the eleventh century; and, of course, the succeeding Solomonic dynasty created a state that incorporated at least two-thirds of its present area. … Even as the Solomonic monarchy weakened, the imperial tradition remained validated in Ethiopia’s monasteries and parish churches. The northern peasantry was continually reminded of Ethiopia’s earlier greatness and exhorted to work toward its renaissance. … [I]f history is to be our guide, [ethnic factionalism] will give way inevitably to renewed national unity as the logic of geography, economics, tradition, and political culture once again come to dominate politics.”

It is, in other words, the continuity of Ethiopian statehood as a reality and as a concept that gives its nationhood weight. This, then, is my definition of a nation: a credible claim of the shared tradition and political destiny of a people, backed by state power or a widely accepted claim to it. Though cultures and ethnicities can exist without the state, the nation implies a claim to Westphalian sovereignty. This is what Ethiopia has over Yugoslavia, which after the death of Tito had a polycentric language (which the Slovenes didn’t speak) and not much else.

But even if you accept this premise, there are holes in this argument. Just because a multiethnic polity with strong traditions has existed for a long time does not mean that it will – or should – continue to exist in the future. Ever since the stagnation and collapse of Haile Selassie’s economic project in the 1960s laid bare the contradictions of a “modernizing” state whose basis for rule was inescapably tied to religious tradition, much of Ethiopian politics has come to be defined by ethnic warfare. As the Emperor’s capitalist programs uprooted farmers and townsfolk and turned them into field and sweatshop laborers, as the countryside and even many towns of the Amhara heartland were neglected in favor of the capital, and as regional authority saw their autonomy dwindle, the idea of a multiethnic Ethiopian society faded. Longstanding ethnic and regional conflicts and grievances strengthened and crystallized into political movements as the old regime grew more centralized and oppressive. When the Empire gave way to the Derg, these trends only worsened, as the army, the police state, and even famine relief were weaponized against opposition movements in the north. Although there remains a basis for Ethiopia as a culturally pluralistic nation, it remains unclear whether this will continue to hold. Just as national identities can form over time, so too can they dissolve. What happened in Eritrea could very well happen elsewhere.

This remains an unsettled problem to this day, as the reformist Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed seeks to pick up the pieces from twenty five years of a disastrous authoritarian experiment in ethnic federation run in accordance with Leninist democratic centralism. In practice, the regime spent most of this period using ethnicity as a tool of control, playing groups against each other to keep the minority Tigrayan People’s Democratic Front in power. Though these conflicts were not by any means caused by this regime, they have undoubtedly been exacerbated to the point of national crisis.

Abiy has called for national unity and free elections, and for now partition appears to be neither imminent nor popular. As I was finishing this piece, his government had signed a peace treaty with the largest separatist organization within its borders, the Ogaden National Liberation Front. Uniquely among his party’s politicians, his popularity appears to transcend ethnic boundaries. However, the old ruling party still remains in place, and ethnic violence and mass displacement has continued. The question of what Ethiopia shall be (if it shall be), and how its people will live in the days to come, has yet to be answered. And I’m certainly not someone who’s qualified to give that answer. I’m not even sure if I’m qualified to ask the question.

Still, if one wishes to support the conclusion that the nation is a useful concept, it is quite hard to exclude Ethiopia from this definition without leaving out a vast number of others. If the foundations of Ethiopia are state violence and cultural imperialism, that is only because these are the foundations on which all nation-states are built. If Ethiopia is not a permanent state of affairs, this is only because all nations are historically contingent, dynamic, and subject to change. This, of course, is a strong argument against the conclusion that the nation is a useful concept. When you dig down to the foundations, every nation is a straw house built on a mountain of shit that could wash away with the next rainstorm. But in the case of Ethiopia, that house exists, is still standing, and people are living in it.

And so, after months of work, writing, and research, I am led to tentatively conclude that Ethiopia is probably a thing that exists. I think. Maybe. Ask me again in five years.

So how does this funny little video game deal with that issue?

(continued)

Sources and Recommended Reading:

Bulatovich, Alexander, trans. Richard Seltzer. Ethiopia Through Russian Eyes.

Holcomb, Bonnie K. The Invention of Ethiopia.

Levine, Donald E. Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society.

Marcus, Harold G. A History of Ethiopia.

Pateman, Roy. Eritrea: Even the Stones Are Burning.

Smith, Denis Mack. Cavour and Garibaldi, 1860: A Study in Political Conflict.