Counter-Review: Civil War

As with most things I find myself liking while everyone else is at best, like my daughter, conflicted, I find myself starting from what the question of what the film thinks it’s doing. The beginning is instructive here. We start in an uncomfortable close-up on Nick Offerman’s nameless President. He is strangely awkward and tentative as he works his way through describing a military victory. Gradually, however, his delivery grows firmer and more confident until it attains a swaggering, brusque confidence. Eventually the scene switches, and we are looking at the President on television, now delivering his remarks in a suitably statesmanlake cadence. Our view expands, and we see a haggard Kirsten Dunst in a hotel room at night as explosions rock the cityscape outside her large glass windows. She carries a camera, which she raises to her eye, pointing it at the President on the TV screen, lining up her shot. Click.

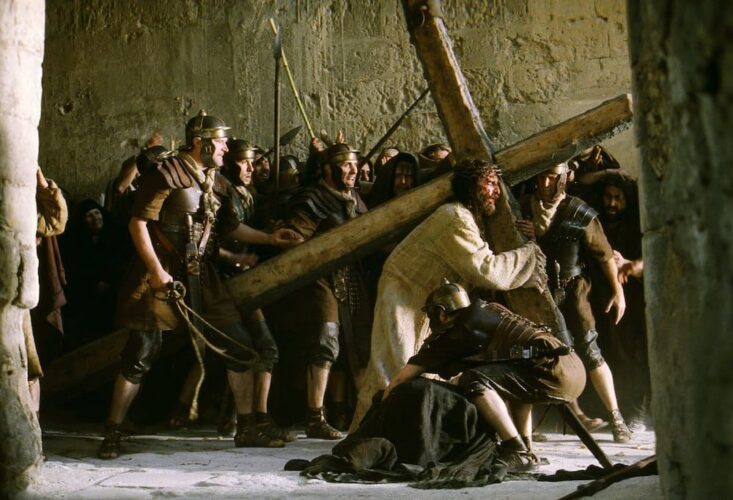

Which is to say that this is a film about the production of the image. This fact frames most decisions the film makes—certainly its choice of protagonists, with the two leads both being war photographers, one of them working a pointedly analog setup of an SLR camera and portable developing kit just to highlight the root mediality of this. As Christine notes, the film makes savvy use of this, alternating between fast-moving, tense action sequences and still photographs, sound cutting in and out to emphasize the contrast between event and image. Even its structure as a travelogue of a journey from New York to Washington pushes it towards a disconnected series of images.

This provides crucial context for what is proving the most controversial aspect of the film: its willful disinterest in the actual politics of the titular civil war. The primary rebellion is the “Western Forces,” an alliance between California and Texas that deliberately cuts across the lines most likely to divide an actual American civil war in the near future. Even within that, there’s little clear sense of who, exactly, is doing what. The film’s tensest sequence, in which the characters are menaced by Jesse Plemons, who demands to know where they’re from and shoots the characters born outside of the US, never actually identifies what side he fights for. The other most intriguing characters, a pair of rainbow-haired soldiers pinned down by a sniper, ostentatiously refuse to disclose what side they’re on. Offerman’s President reveals no political positions save for autocracy.

The absurdity of this defiant effort to produce an apolitical film about an American civil war has proven vexing for critics. Even those willing to grant the notion of apolitical art—and I’m on record rejecting the possibility entirely—are struck by the impossibility of this task. Garland, who is not an idiot, can surely see it as well. But the quixotic attempt serves the same purpose as those sonic cuts, highlighting the act of representation, making us aware that we are looking not at an American civil war but the image of one.

In this regard what Christine highlights as the film’s strength—its repeated arrival at chilling, harrowing images—is the whole of its point.…

Some nine years ago I wrote an essay about Peter Harness, then primarily known as a Doctor Who writer, perhaps most notable for writing Kill the Moon, a story for which I wrote a rave review that was, shall we say, somewhat out of step with the critical consensus. In this essay, I offered some anticipation of an imagined future Peter Harness project in which the promise of his Doctor Who work and his largely underrated adaptation of Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell would be paid off.

Some nine years ago I wrote an essay about Peter Harness, then primarily known as a Doctor Who writer, perhaps most notable for writing Kill the Moon, a story for which I wrote a rave review that was, shall we say, somewhat out of step with the critical consensus. In this essay, I offered some anticipation of an imagined future Peter Harness project in which the promise of his Doctor Who work and his largely underrated adaptation of Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell would be paid off.

…

…