A Brief Treatise on the Rules of Thrones 3.10: Mhysa

|

| Fame, it’s not your brain, it’s just the flame That burns your change to keep you insane |

The choir goes off. The board is laid out thusly:

Lions of King’s Landing: Tyrion Lannister, Jaime Lannister, Cersei Lannister, Tywin Lannister

Dragons of Yunkai: Daenerys Targaryen

Direwolves of the Wall: Jon Snow, Bran Stark

Bears of Yunkai: Jorah Mormont

Ships of Dragonstone: Davos Seaworth

Burning Hearts of Dragonstone: Stannis Baratheon, Melisandre

Direwolves of King’s Landing: Sansa Stark

Direwolves of the Twins: Arya Stark

The Kraken, Theon Greyjoy

Stags of King’s Landing: Joffrey Baratheon

Bows of the Wall: Ygritte

Archers of the Wall: Samwell Tarly

Stags of Dragonstone: Gendry

Dogs of the Twins: Sandor Clegane

Spiders of King’s Landing: Varys

Flowers of King’s Landing: Shae

Winterfell is abandoned and in ruins.

The episode is in seventeen parts. The first part runs two minutes and is set at the Twins. The opening image is of Roose Bolton atop the battlements.

The second runs nine minutes and is set in King’s Landing. The transition is by family, from Arya to Sansa Stark.

The third runs two minutes and is set at the Wall. The transition is by family, from Sansa to Bran Stark.

The fourth runs two minutes and is set at the Twins. The transition is by dialogue, from Bran talking about the horrors of violating guest right to Walder Frey.

The fifth runs four minutes and is set at the Dreadfort. The transition is by dialogue, from Roose explaining what actually happened at Winterfell to Ramsey pretending to eat Theon’s penis.

The sixth runs three minutes and is set at the Wall. The transition is by hard cut, from Reek whimpering his name to Bran awakening.

The seventh runs three minutes and is set on Pyke. The transition is by hard cut, from Bran to an establishing shot of Pyke.

The eighth runs two minutes and is set at the Wall. The transition is by hard cut, from Yara setting sail to Bran inspecting the Dragonglass.

The ninth runs three minutes and is set on Dragonstone. The transition is by hard cut, from Bran and company walking out of the Wall to Davos entering the jails.

The tenth runs six minutes and is in two sections; it is set in King’s Landing. The first section is three minutes long; the transition is by dialogue, from Davos talking about his son’s death to Shae looking out at the Blackwater, and from Davos and Gendry talking about not being highborn to Varys and Shae doing the same. The second section is three minutes long; the transition is by dialogue, from Shae and Varys talking about Tyrion to Tyrion.

The eleventh part runs two minutes and is set on the road outside the Twins. The transition is by dialogue, from Tyrion and Cersei talking about the horrible things they do to their enemies to the Hound and Arya riding past some Freys joking about Catelyn’s death.

The twelfth runs five minutes and is in two sections; it is set in and around the Wall. The first section is one minute long; the transition is by family, from Arya Stark to Jon Snow. The second section is four minutes long; the transition is by hard cut, from Jon riding off to an establishing shot of Castle Black.

The thirteenth part runs six minutes and is set on Dragonstone. The transition is by causality, from Maester Aemon sending out the ravens to Davos receiving his message.

The fourteenth runs one minute and is set at the Wall. The transition is by image, from Gendry rowing away to Jon arriving at the Wall.

The fifteenth runs one minute and is set in King’s Landing. The transition is by image, from Jon arriving at King’s Landing to Jaime arriving at King’s Landing.

The sixteenth runs three minutes and is set on Dragonstone. The transition is by hard cut, from Cersei staring at Jaime to Stannis being frustrated.

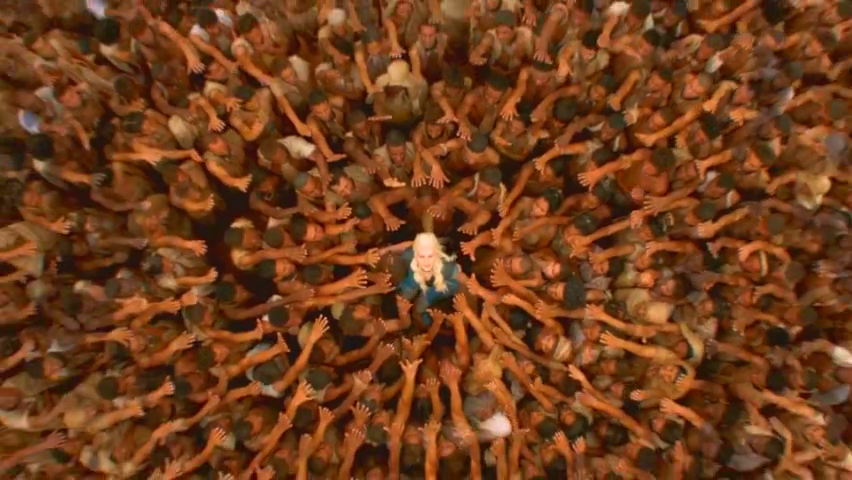

The seventeenth runs two minutes and is set in Yunkai. The transition is by hard cut, from Melisandre to an establishing shot of Daenerys and company. The final image is of Daenerys completing a Full Web. She’s playing white.

Analysis

The period from 1900-1929 is known as the “dead-ball era” in baseball – a sustained period in which the average number of runs scored per game dropped, falling to a mere 3.4 in 1908, before finally rebounding with the emergence of Babe Ruth. It is not fair to say that this marked a failure of baseball; indeed, for certain types of fans the nervy, strategic style of play that emerged, based heavily on stolen bases, marks a sort of apotheosis of play. For most, however, it has to be viewed as an aberration – an odd, transitional period between the initial formulation of baseball as a sport (notably a few years before 1900 was a massive spike in runs per game that has never come close to being equalled) and the modern era.

I doubt I need to spell out where this metaphor is going. It is by no means the case that the third season is a bad one; indeed, in terms of overall quality it may not even be the worst run of play the game has ever experienced, although I am inclined to argue that the flaws of the fifth season are balanced by the astonishing successes in redeeming shockingly poor source material. But it is still a strange, half-formulated thing, existing at an uncertain midpoint between adaptation and origination, a transformation-in-progress in how the show thinks of itself as television. For all its strengths, and there are still many, it is largely the worst of both worlds: unclear about what it wants to say, awkwardly structured, and prone to forgetting what it does well in the service of trying to fix what it doesn’t yet.

For the most part, “Mhysa” exemplifies this. Its biggest problem is simple: it’s a season finale saddled with the fact that the only one of its characters to have actually reached something designed to be an ending for them is Bran, and that’s only because he’s not actually in the last quarter of A Storm of Swords. Almost everything in the episode is thus awkwardly pressed into service, made to perform functions they were never designed to. The biggest offender, by some margin, is Daenerys, whose scene is given preposterously overburdened weight by dint of having to be a season-ending shot and title drop despite in every regard being by literally every standard the second most impressive “Daenerys pwns” cliffhanger of the season.

But these problems amount to putting a lot of weight on an already dodgy decision. Yes, the mechanics of shooting a large crowd scene like this have certain constraints; Game of Thrones is shooting Daenerys’s sequences in Morocco, from whence its extras are hired. The demographics of Morocco are what they are. And Daenerys’s larger narrative over the course of the next two seasons can fairly be described as a critique of interventionalist imperialism. Nevertheless, the scene of a massive crowd of brown people shouting out with religious devotion to their white liberator as they carry her aloft and her dragons shriek overhead to signal the approval of the underlying mythic structures of the cosmos is absolutely painful to watch. Yes, it’s made worse by the decision to give it unnecessary bombast as an ending. But it’s also just a garish and poorly-chosen image in the first place.

But, of course, what else would you even use as an ending? The Jaime/Cersei reunion? Bran disappearing into the whiteout at the end of the tunnel? There aren’t really any good options. Indeed, most of the other scenes have a similarly overburdened feeling. Kit Harrington is completely out to sea in the tacked-on Jon/Ygritte scene, and while some of it is that he’s consistently failed to sell romance all season, some of it is simply that the scene is completely and utterly pointless, tacked on solely so that the Jon/Ygritte relationship resolves in the final episode, despite the fact that this creates the utterly contrived spectacle of Jon Snow riding off injured in two consecutive episodes.

Similarly wonky is Stannis’s plot, which occupies an outsized twelve minutes (all of King’s Landing gets sixteen) for little reason save that Robb has to die to kick things off here. Again, it’s the urge to make this an ending that overburdens the plot. In particular, the stagey melodrama of the “what’s the life of one bastard boy against a kingdom” scene is awkward in a way the show usually avoids, not least because we have to do the whole thing again a few scenes later in order to get Stannis headed to the Wall. Which, of course, Season Four then proceeds not to do. You can tell that they’re working a fair amount of this out on the hoof, in other words. (Likewise, and not entirely unrelatedly, the weird jaunt over to the Greyjoys.)

And yet this sequence also points to the episode, and indeed the season’s redemption, which is as always its small moments. Indeed, if “Mhysa” is looked at as a disposable middle episode of a twenty-episode adaptation its virtues become apparent. (That’s not to say, of course, that Seasons Three and Four are sensibly viewed that way.) For instance, the transition from Davos and Gendry talking about how poor people like them will never really be like the gentry to Varys and Shae talking about how foreigners like them never will be either, which is one of the most affecting things in the whole of the series, entirely earning its unsubtlety. Indeed, King’s Landing has much of what works best in this episode: the one scene we get that offers a taste of what Tyrion and Sansa might be like in other circumstances, the Joffrey/Tywin confrontation is a thing of beauty (Conelith Hill has a delightful eyeroll at one point), and Nikolaj Coster-Waldau has never been better than in his near-wordless scene with Lena Headey.

But if we are to end our analysis of this troubled period of play on a bright note, the clear choice is Maisie Williams, whose performance almost justifies the Red Wedding. Inasmuch as it is a reiteration of the end of the first season – and the structural callback is neither incidental nor accidental – the development of Arya’s character that it indicates is profound. In Season One she was counseled not to look, and she didn’t. This time she does, and it’s so much worse. Her chilling, dissociated performance of a harmless little girl is intense and unsettling in ways no amount of fake blood can equal, the most complete and harrowing execution of the “children’s fantasy heroine gone wrong” structure she represents. It’s a straightforward reminder of the game’s potential. And a perfect setup for its creative zenith.

A Brief Treatise on the Rules of Thrones will return later in 2016.

March 28, 2016 @ 9:58 am

That second one would make a good callback to the first season, wouldn’t it? Though you’d have to strain to think of a reason for it to call back to that.

March 28, 2016 @ 11:32 am

There is a pattern going on with the tunnels anyway – we see people pass through the Wall in the last episode of each of the first three seasons, as well as at the very beginning of the series. Season 4 stretches it a little, as Jon goes through at the very end of episode 9, and emerges at the start of episode 10. I think those are the only times we ever see anyone go through (though I haven’t seen season 5 yet), so there’s definitely a structural game being played there.

Also, we only ever see people going north (that is, the ones who actually make it through). That makes sense, given how the Wall separates the land of the living from the land of the dead (a point highlighted by the season 2 tunnel sequence, in Daenerys’s vision, where she passes through the tunnel to meet Drogo, an image which is itself foreshadowed by the juxtaposition of Drogo’s death with the tunnel sequence in season 1).

The most basic explanation of associating those threshold-crossing sequences with the turn of the seasons would be that it simply denotes the end of each section of the story, though maybe something more thematically eloquent could be discerned with a bit of work. (Mind you, in this story the concept of the “season” has a certain thematic resonance in itself.)

March 28, 2016 @ 12:06 pm

Whatever the limitations of the Stannis section, “Because I’m a slow learner” is an air-punch moment for me. It comes across as Davos shouldering through the fourth wall to give two fingers to the writers.

March 28, 2016 @ 12:11 pm

Bother – that wasn’t meant to be a reply.

While I’m here, though, I should have mentioned it was Daru who pointed out the juxtaposition of the season 1 tunnel sequence with Drogo’s death.

May 10, 2016 @ 7:51 am

Thanks yeah! Been ages since I commented, been reading certainly but been less able to keep up with commenting recently.

I think yes, that the use of the image of passing through a tunnel or doorway would have been really evocative. Especially as Bran was making an actual magical transition of note. And I know it’s loose, but the theme or passing though would arise again with Jon resurrecting in season 5 and the title of the episode called The Door.

April 25, 2016 @ 9:46 am

So, I was rewatching season 4, and it turns out there’s a bit in the tunnel when Gren and Edd come back. So bang goes that theory.

Foiled!

March 28, 2016 @ 11:52 am

I think “completely and utterly pointless” is an unfair description of the Jon-Ygritte scene. I mean, it casts the end of that relationship in a very different way from what would have been there if they had just left it after the previous episode. In that, they’re separated by the inconvenient practicalities of being in opposing armies (after a fight in which she would actually have taken his side – Jon knocking Ygritte down so that she won’t kill any of her people on his behalf is a lovely little understated detail). This takes it to Because He Was Her Man And He Done Her Wrong. Which may or may not be a good decision, but it definitely does something significant to that story. Also it works for me, though that may be just because I’m a sucker for Ygritte.

March 28, 2016 @ 1:16 pm

The big Lannister-table scene is gorgeous (I love the moment when Tywin’s hand with the letter drops), but it represents the peak of my difficulty with Conleth Hill’s performance as Varys, which is that it’s, well, too much fun. He gives some great theatrical reactions to things, but it seems wrong for the character at times. A subtle court intriguer and master spy, and especially one whose gifts and approach are supposed to be informed by acting talent and training, really ought to be more inscrutable, better able to hide feelings which it would be impolitic to show.

Take for instance his lemon-sucking expression as Littlefinger is promoted – in front of the whole court, he would surely make a point of not giving anyone the satisfaction of seeing him being the least bit bothered. Here, he not only gives away more than he should, but attention is actually drawn to it by having Cersei notice, and him notice her noticing.

I realise there is a line to be trodden here between strict naturalistic representation of how such a person would behave, and the need to communicate what he is thinking to the audience. It is possible, though, in screen acting at least, to convey both inscrutability and the feelings it is concealing – Mark Rylance in Wolf Hall leaps to minf. Admittedly, it must be a lot harder to accomplish that without the screen time, close-ups and general attention accruing to a protagonist.

March 28, 2016 @ 9:59 pm

Regarding the need to make endings for characters, of course it’s equally valid to make a beginning. Just about every character signs off season 1 with a beginning, and they’re about as common as endings in subsequent episode 10s. Stannis makes what turned out to be a false start here, but at least he got to the Wall eventually. The one that really turned out to be going nowhere was the King’s Landing strand, and that’s an issue concerning the season as a whole.

Apart from the similarly abortive Tyrion-Sansa marriage, the whole King’s Landing plot this season seems to occupied with setting up a season 4 power struggle pitting Tywin against Joffrey and the Tyrells, with Cersei caught in the middle. The establishment of Olenna’s skills as a politician capable of measuring up to Tywin and of Margaery’s ability to handle Joffrey, Joffrey’s increasing distance from Cersei and nascent resentment of Tywin’s dominance, Cersei’s fear of losing Joffrey to Margaery and unsuccessful efforts to persuade Tywin of the danger posed by the Tyrells – it all seems to be laying the groundwork, and the eruption of open antagonism between Tywin and Joffrey here looks like the final preparatory step for it to get going properly next season.

Then it didn’t happen, leaving me thinking “so what was the point of all that then?”

March 30, 2016 @ 11:33 pm

I never noticed the “colonial overtones at the time, partIy wasn’t watching that closely, perhaps also because I’m focused on Game of Thrones world when watching, and just think “that’s what people in Essos look like”, and “Daenerys is a Targaryen, so she’s blonde” etc,

It’s not that I’m so naive that I don’t know there’s an intersection between fantasy fiction and reality, more that in GoT I imagine the intersections to be oblique – perfectly inexact – while at the same time – at least with regards to the books, more or less expressly deliberate.