A Consistently Inaccurately Named Trilogy Part I: Brick

I first encountered the work of Rian Johnson while reading about Terry Gilliam’s My Neighbor Totoro remake Tideland on Wikipedia, where I stumbled across the factoid that Johnson had declared it and Darren Aronofsky’s The Fountain to be the two best films of 2006. This claim was notable for being A) self-evidently correct and B) a completely insane statement that nobody but me would actually make. And so I was immediately fascinated by this previously unheard of filmmaker and decided that, on the basis of his taste alone, I’d check out his existent film, a high school noir called Brick. (Also, it was only like $5 on Amazon.) Since then I’ve followed his career on the general logic that he was going to get really big some day. Which, sure enough, he did, so let’s put that knowledge to populist use. (And I’ll just spoil it up front, my favorite Johnson film is The Brothers Bloom, my least favorite is Looper.)

I first encountered the work of Rian Johnson while reading about Terry Gilliam’s My Neighbor Totoro remake Tideland on Wikipedia, where I stumbled across the factoid that Johnson had declared it and Darren Aronofsky’s The Fountain to be the two best films of 2006. This claim was notable for being A) self-evidently correct and B) a completely insane statement that nobody but me would actually make. And so I was immediately fascinated by this previously unheard of filmmaker and decided that, on the basis of his taste alone, I’d check out his existent film, a high school noir called Brick. (Also, it was only like $5 on Amazon.) Since then I’ve followed his career on the general logic that he was going to get really big some day. Which, sure enough, he did, so let’s put that knowledge to populist use. (And I’ll just spoil it up front, my favorite Johnson film is The Brothers Bloom, my least favorite is Looper.)

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Brick is that it isn’t funny. Sure, there are moments that are humorous – the recurring urgent discussions about who people eat lunch with, for instance, or any scene whatsoever with the Pin’s mother. But although these things are funny, Johnson makes no effort whatsoever to actually get the viewer to laugh. The scenes are not played with comic timing, the humorous aspects are not pushed to the foreground, and none of the actors deliver their lines as if looking for the laugh.

What’s unusual about this is not that it’s an incongruous genre mashup played straight. What’s unusual is that one of the genres is high school. When you take the other great incongruous high school genre mashup to launch its creator to directing a major Disney franchise film, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, it took place not only in a high school, but in an overtly funny high school of the sort familiar from Saved by the Bell or Ferris Bueler’s Day Off or, if you prefer to go back further, Happy Days or Grease. It’s not that Brick is the only serious high school movie ever made, but the core texts of the genre are those comedies or ones like them. So to do a genre mashup that is an objectively funny idea when one of the genres is largely comedic and have it be deadly serious is, on the face of it, interesting.

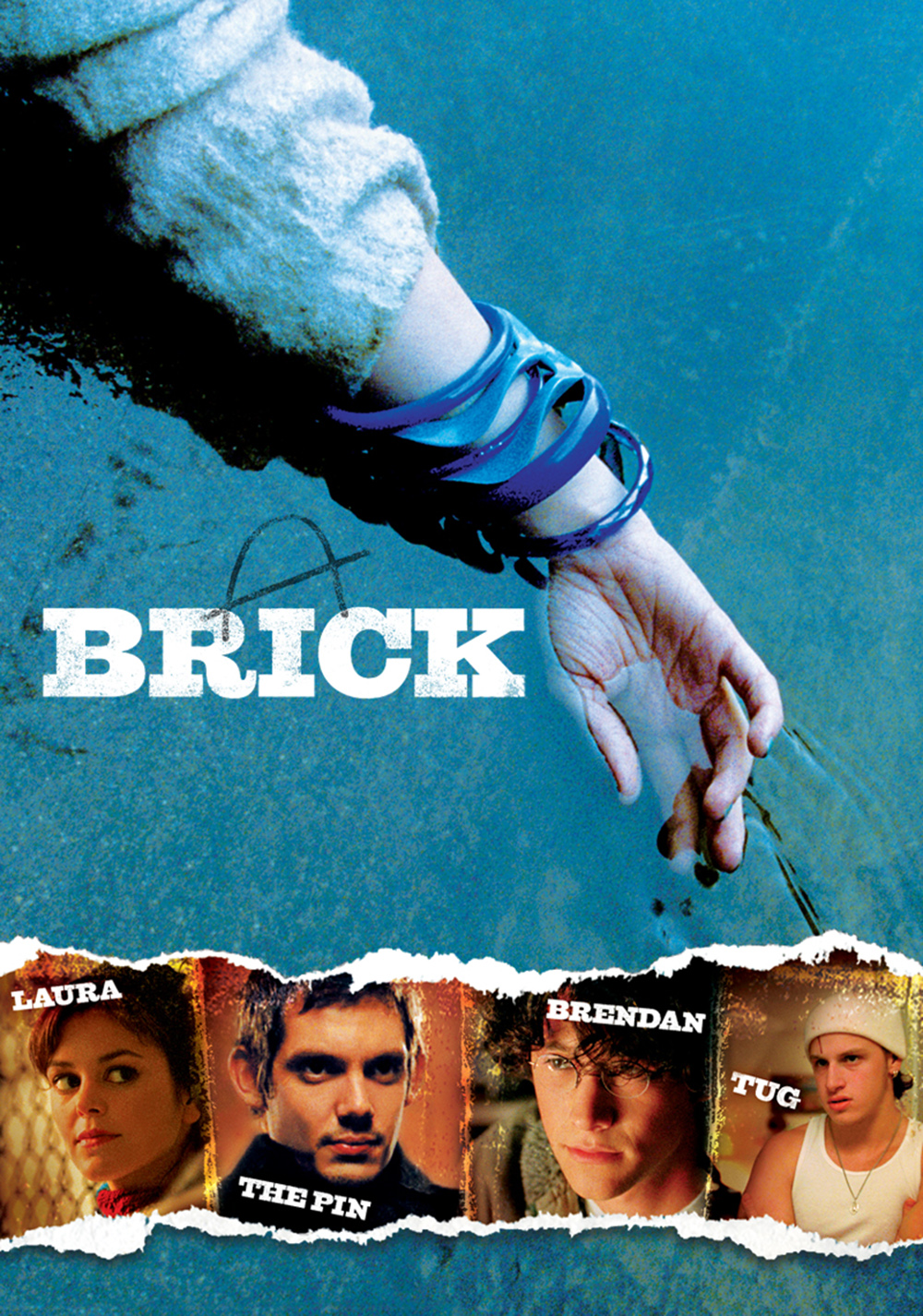

A genre mashup, done well, is about liminal spaces. In Brick, the key one is the tunnel where Emily is murdered. It’s where the film opens, and it returns there constantly, with Johnson’s camera endlessly cycling back to open mouth and to characters sinking into and emerging out of its darkness. It also returns constantly to the image of Emily’s arm lying in the water, her murder being the key event to take place in this space. This image also features on most of the film’s posters, becoming, along with the line drawing that represents the tunnel, the film’s main visual icon.

Obviously, this is a bit icky. And there’s not really a way around that ickiness. There’s no serious way to argue that this is secretly a feminist film or anything like that. It bombs the Bechdel test at the second hurdle, with none of its three female characters ever having a conversation. Nor are any of them particularly positive portrayals – there’s the drug addict with multiple sex partners who gets murdered, the femme fatale who sets her up, and the main character’s lying ex-girlfriend, who’s just a different sort of femme fatale. It’s noir, so nobody comes off well exactly, but this is a film that’s definitely more interested in exploring masculinity than it is in women.

Thankfully its take on masculinity is compelling. The main character, Joseph Gordon Levitt’s Brendan, is repeatedly defined in terms of his desire to protect Emily and keep her safe. This, however, is not treated as a positive thing. At its best, it is something that makes Brendan slightly pathetic. At its worst, it’s visibly suffocating and borderline abusive. It’s not that Emily doesn’t need help – she’s locked into a visible downward spiral. Rather, the problem is that Brendan needs to protect her and, even more importantly, protect his (fundamentally fictitious) image of her. Certainly his protection of her is not really done with particular attention to her best interests or indeed consent – their breakup was over his decision to get in with a small-time drug dealer she’d befriended just to rat him out to the principal (portrayed by Richard Roundtree, another hilarious decision played straight). This isn’t just masculinity played with realistic toxicity, it’s played with genuinely adolescent toxicity – unhealthy and destructive in the ways that well-intentioned teenage boys often are.

This makes it one of relatively few aspects of the film to really come from the high school side of the ledger instead of the noir one. In some ways this is unsurprising – given that it turns its back on the genre’s comedic underpinning. But this fact clarifies a key aspect of how Brick manages its genre mashup. For the most part, it’s not interested in using noir to illuminate truths about high school that other stories miss. Instead, it’s using the high school setting to refresh noir. As Johnson put it in an interview, “the second you do a modern movie that has men in hats and alleyways and venetian blinds shadows — it’s not that it can’t be good, it can be terrific, but you know instantly where you are. You can categorize it in your head.” Putting it in a high school instead of the 1920s breaks that, allowing the genre to be unfamiliar again.

It’s a good trick, which is all you actually need for a first film. I mean, that and rock solid execution, which Johnson has in spades. Brick is a microbudget film, but it looks absolutely gorgeous. Johnson’s camera angles are striking without being distracting. He often picks low shots that let the characters loom in the frame, giving a sense of weight and grandeur to them even though they’re high school students. (This is the rare film where casting twenty-somethings as teenagers works for reasons beyond “they’re better actors.” Although certainly another one of Johnson’s strengths is his casting, grabbing an on the rise Joseph Gordon-Levitt along with Emile de Ravin, and the criminally underrated Nora Zehetner.) Alternatively, he picks close-ups, often shot with fairly wide angle lenses, and a huge number of POV shots that serve to focus the film on Brendan’s perspective. This latter move has the useful side effect of doing the work usually accomplished by hard-boiled narration, thus avoiding an aesthetic decision that would have been hard not to have be funny, and, worse yet, inadvertently funny. (c.f. “Sushi, that’s what my ex-wife called me.”)

The result is not a film with the brash grandeur of Tideland or The Fountain. But those are, respectively, a late-career film and a director getting his first taste of a real budget. The films to compare it to are Time Bandits and Pi. If anything, Brick, by dint of the dissonance in scale between noir and high school, has more of a sense of grandeur than Gilliam and Aronofsky’s debuts, just because it’s a film that’s in part about its sense of scale. To make the Buffy comparison again, just as that show trades on “in high school everything feels like the end of the world,” Brick trades on the expansion of adolescent male alienation into the full-blown grime and glamour of noir.

And yet on the other hand, there is a sense of control and discipline to Brick that neither Pi nor Time Bandits has. Those films, like the later career works that entrance both Johnson and me, are fundamentally committed to a level of excess. Brick, on the other hand, in its studious lack of humor, has a fundamental instinct not to push things too far. It’s a much more inward looking film. There’s an analogy Eddie Campbell makes in The From Hell Companion where he talks about having loaded From Hell up with a certain amount of creative fuel generated by its formal concepts, and this fuel being exactly sufficient to get the project over the finish line. And the description applies to Brick as well – it’s a film about showing what its creative and aesthetic engine is capable of.

In that regard, perhaps a more accurate way to look at Brick’s comparative lack of bombast is to accept that the answer to that question is not interesting because of its scope. Rather, it is that such an improbable and rickety engine, bolted together from two radically different approaches in a fundamentally counterintuitive way, should run so smoothly and straightforwardly. Its trick is making it look easy.And I mean genuinely easy – not the ostentatious “aren’t we clever for pulling this off so well” polish of, say, Memento (and I reckon I’ll do the Nolan Batfilms to complete the trilogy trilogy, incidentally) but rather a film that seems good instead of impressive.

I think, to be honest, that it’s a better film than Time Bandits or Pi. That’s not, obviously, a claim that Johnson is better than Gilliam or Aronofsky. But it struck me as clear from his debut that he was someone who could get there. And as he had another film coming out in a few months that I’d already seen a trailer for and thought looked fine, I figured I’d check it out when it wandered by Gainesville on its infuriatingly meandering tour of small indie theaters (and, subsequently, real ones). Which brings us neatly to The Brothers Bloom.

July 4, 2017 @ 3:12 pm

Even robots appreciate the Sandifer approach.

Speaking of the Sandifer approach, the Dark Knight Trilogy seems like an odd choice for a third part to this trilogy, most of all because it actually is a trilogy. Unless you’re, wisely, deciding to include the Prestige and Inception as entries in the trilogy, which they self-evidently are.

That just leaves the question of what the fourth entry in your trilogy will be.

July 4, 2017 @ 5:04 pm

Well, the reason this one is consistently inaccurately named is that there’s three of them, but they’re not actually linked or conceived of as a series. The Nolan films will probably be called An Accurately Named Trilogy.

I can neither confirm nor deny plans for a part four.

July 6, 2017 @ 12:34 am

Well, if you do it would be fitting to go with one on the Anthony Hopkins Lecter films, given that it’s probably going to be written after Proverbs of Hell 39/39.

July 6, 2017 @ 3:26 am

An Inaccurately Ordered Trilogy!

July 4, 2017 @ 9:28 pm

I’m looking forward to this series. I think LOOPER does a classic example of narrative substitution. You think it’s a pulp gangster film, even though it’s a love story about selfish desire.

Johnson’s got a really interesting view on love and passion, refusing to see this as always the net positive that it’s usually treated in Hollywood films, especially genre films. His two ‘noirs’ show how love can be corrupted into something driven by greed. It’s quite different when even the films of major directors (and ones who got their start in ways similar to Johnson) such as Paul Thomas Anderson and the Coen Brothers treat love as the redeeming trait of their characters, not the damning one.

July 5, 2017 @ 3:55 am

(Time Bandits was not Gilliam’s debut.)