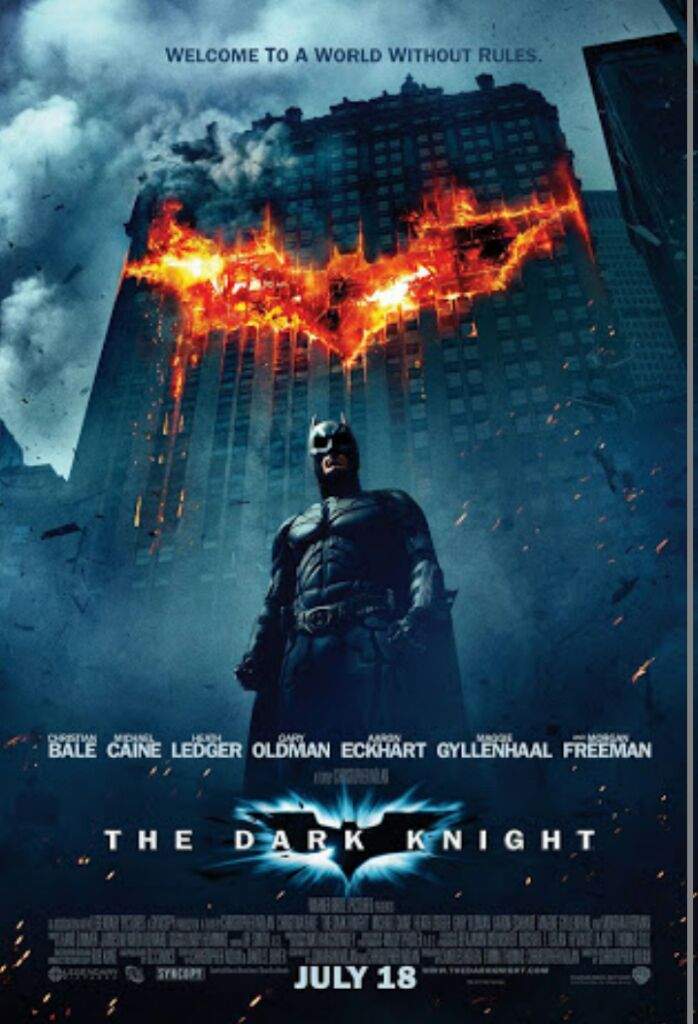

An Accurately Named Trilogy II: The Dark Knight

It seems silly to start anywhere besides the Joker. We’ll set aside the cynical but not entirely unfounded question of whether the performance would be as celebrated as it is were it not for Heath Ledger’s untimely death and the ghoulish speculation (since refuted) that the psychological intensity of the role was a cause. Sure, it’s tough to imagine a Batman film winning an acting Oscar under less tragic circumstances, but that’s in no way what’s interesting here. What’s interesting is that Ledger and Nolan took the most oversignified character in Batman mythos (and yes, of course I’m including the big rodent himself) and offered a game-changing take on him. The hunched, disheveled figure with a Glasgow smile is a new angle, skewing the Joker towards a materialism that is generally precisely what’s discarded in other efforts to make him more grandiosely crazy. Ledger and Nolan offered a new way for the Joker to be.

It seems silly to start anywhere besides the Joker. We’ll set aside the cynical but not entirely unfounded question of whether the performance would be as celebrated as it is were it not for Heath Ledger’s untimely death and the ghoulish speculation (since refuted) that the psychological intensity of the role was a cause. Sure, it’s tough to imagine a Batman film winning an acting Oscar under less tragic circumstances, but that’s in no way what’s interesting here. What’s interesting is that Ledger and Nolan took the most oversignified character in Batman mythos (and yes, of course I’m including the big rodent himself) and offered a game-changing take on him. The hunched, disheveled figure with a Glasgow smile is a new angle, skewing the Joker towards a materialism that is generally precisely what’s discarded in other efforts to make him more grandiosely crazy. Ledger and Nolan offered a new way for the Joker to be.

By some margin the least interesting parts of this are the most often remarked upon. Yes, Ledger’s schlubby maniac was an easier fit for a certain strain of geek masculinity than the more overtly queer portrayals that came before him. But frankly, anybody who needed reassurance that the Joker’s makeup was “like warpaint” before they’d dress as him for Halloween needs to be fired into the sun. “Why so serious” is a great marketing line, but it’s a trivial part of the character’s personality – a line he uses in one of the mutually contradictory origin stories he gives – and reducing Ledger’s take to his leering transgressiveness is how you get Jared Leto’s performance in Suicide Squad.

To understand what’s going on with Ledger’s Joker, it’s necessary to understand the basic oversignification of the character. For that, let’s turn fleetingly to what is both the best comic story written about him and the low point of Alan Moore’s career, Batman: The Killing Joke. (This being where Nolan’s “multiple contradictory origins” idea originates.) For all that Moore crafts a typically symbolically rich take on the Joker, the big problem with the story, as Moore readily admits, is that he didn’t define the Joker as anything other than Batman’s archnemesis. He represents nothing save for a particular limit point for Batman – an irreducible reality of his mythos interesting for few reasons other than that homicidal clowns with good visual design are kinda cool.

This is not what the Joker in The Dark Knight is doing, although it’s easy to miss that fact. The centrist liberalism that is the default setting of most popular culture means that we’re most used to villains who are cuddly versions of fascism: Voldemort, the Empire, the Daleks, etc. It’s easy to make too much of this – the defanged fascists of popular culture villainy are generally so cartoonishly that if they have any political effect, it’s to blind us to fascists that don’t literally call themselves Death Eaters, have the Imperial March as their theme song, or shriek “EXTERMINATE” a lot. But it means we’re strangely unused to seeing a villain who’s applying the same cartoonish excess to leftism. Which means, in practice, that it’s easy to miss that the Joker is a leftist villain, with the same basic relationship to anarchism that Darth Vader has to fascism.

It’s certainly not that the Joker is the only villain in pop culture who can be described as “anarchic.” But it is by any measure a shorter list than the fascism analogues, and more to the point, few of them are quite so defined as to get an ostentatious villain monologue about the evils of “schemers” and “plans” that ends in a declaration that they’re an agent of anarchy and chaos. Fewer still get to deliver the monologue opposite a semi-fascistic narrative of powerful rich men running elaborate surveillance operations.

One of my favorite things ever posted to my site is Jack’s TARDIS Eruditorum guest post on Merlin. He sent it to me late on Christmas Eve so I ended up reading it on Christmas morning, happily ignoring a stack of presents in favor of his hymn to the glories of villains. His argument is that villains, as the force in a story that wants to change the status quo, are an occasion where “the radical howl be heard, even if in a distant and garbled form.” But this garbling mostly comes from the routine use of the liberalism/fascism opposition. Because fascism is little more than the acceleration of liberalism’s worst instincts, this opposition tends to collapse. To use one of Jack’s examples, Voldemort may be marked as a fascist due to his zealotry over racial purism, but this ends up being a mask for the fact that Rowling’s “good” wizard society is built on systemic racism of its own, including literal fucking slavery.

But the Joker sidesteps that aporia. He doesn’t embody the same flaws as the heroes only in black. Rather, he offers an actual ideological difference. Batman endorses a world ruled by militarized power wedded to a mythic and incorruptible symbol. (And it’s worth noting that Harvey Dent’s “maverick tough on crime prosecutor” personality is very, very Bush era.) The Joker endorses burning that world down. Tellingly, the Joker doesn’t get what the sort of standard villain moment that will be afforded to Bane whereby whatever political alternative he offers is revealed as disingenuous, typically because the villain is actually a genocidal maniac. The Joker is never presented as anything other than a force of violence attempting to dismantle Gotham’s society. There’s no reversal. He just wants to watch the world burn. This fact is presented to the audience as a self-evident horror, the possibility that anyone might nod with agreement not even entertained.

I don’t want to go too far towards “the Joker was right” here, although I’ll admit that’s more because of the historic lameness of that argument than out of any particularly substantive objection. The reasons he’s wrong mostly come down to the distortions necessary to transmute anarchism into straightforward villainy. He’s a sadist who blows up civilians for no reason other than the fun of it. But what interests me is how terrible a job Nolan does selling the apparently straightforward case that he’s wrong. His final comeuppance – the stunt with the two boats – may well be the single worst sequence Christopher Nolan has ever committed to film.

To recap, the Joker has taken two boats – one a prison transport ship, the other full of civilians – and put bombs on each one, with the detonators given to the people on the other boat. The point is, as he puts it, a “social experiment” to see who blows who up first. Its resolution is that neither boat blows up the other because, in one case, a bussinessman is unable to bring himself to do it while in the other what the script describes as a “huge, tattooed prisoner” (played, of course, by a suitably intimidating looking black actor) demands to be given the detonator so that he can make the hard decision, only to heroically chuck it out a window. It is gobsmackingly schmaltzy, and completely lacking in any conviction – a hopelessly contrived affirmation of the basic goodness of human nature that literally nothing else anywhere in Nolan’s trilogy backs up. It’s as though the film recognizes the suppressed possibility that the Joker might not be as self-evidently awful as it desperately wants him to be and goes to ostentatious lengths to deny a possibility that it can’t even acknowledge in the first place.

And no wonder. In marked contrast to R’as al Ghul, whose sense of Gotham’s decadence seemed utterly contradictory given his own methodology and whose solution was simply to eliminate the entire city, the Joker clearly wants the city to survive in what he views as a better form, and is thoroughly coherent in diagnosing its problems. Consider his monologue about how “nobody panics when things go according to plan, even if the plan is horrifying. If tomorrow I tell the press that like a gangbanger will get shot or a truckload of soldiers will be blown up, nobody panics. because it’s all part of the plan,” which is, notably, a more coherent response to R’as al Ghul’s whole “we tried to destroy Gotham with economics” thing than literally anything Batman says over the entirety of Batman Begins.

Indeed, this is in some regards the crux of the problem (if one wants to call it a problem) with the Joker. Yes, he bypasses the tedious aporia created by the liberalism/fascism dualism of a lot of hero/villain pairings, but he does so in pursuit of a different sort of breakdown. The truth of the matter is that Gotham, as envisaged by Nolan, is a strong case for anarchism. When the world is systemically corrupt and the only apparent alternative is violent authoritarianism, burning it down is an entirely rational response. The sensible points of disagreement with the Joker are over tactics, not goals.

And so instead of toppling into the sterile incoherence of what is, if not a false opposition, at least a heavily overstated one, Nolan goes for the far more generative incoherence of incorporating an actually substantial opposition and then trying to render it unspeakable. The Joker, despite being a shockingly cogent character, is treated as unfathomable by essentially everyone else in the film. Even the canonical attempt to account for him – Alfred’s “some men just want to watch the world burn” – runs aground on the suppressed reality that Alfred’s time in Burma was almost certainly as a mercenary in the post-colonial civil war there, immediately adjacent to the heroin trade, and that resistance to the efforts of a bunch of mercs who, let’s not forget, eventually literally did burn down an entire forest is not, in fact, “wanting to watch the world burn” just because you don’t keep the corrupt profits. (If Tat Wood or Lawrence Miles ever move on to About Bat-Time, “What Was Alfred Doing in Burma” is an obvious essay. One suspects that Caine, at least, thought he was playing a World War II veteran – he’s suggested a backstory for Alfred predicated on him serving in the SAS during “the war,” which would make him being in Burma more sensible. Unfortunately, it would mean Alfred is around 85 years old in The Dark Knight, which would put him in his early 90s for The Dark Knight Rises, which is a stretch. But if we assume that Alfred is roughly the same age as Michael Caine, who was born in 1933, putting him in Burma prior to its independence in 1948 is difficult. Ultimately, description of how “my friends and I were working for the local government” makes me more inclined towards the interpretation that he was a mercenary working after independence.)

Where this becomes a problem is, broadly speaking, the end of the film. Not just in the already discussed pathetic resolution to the boats situation, but in the basic narrative structure whereby the Joker gives way to Two-Face as a villain, only for the film to discover that it’s running out of time and doesn’t have the space to make his gimmick anything other than a weird transformation with no clear motivation beyond “well they fridged Maggie Gyllenhaal, so I guess Harvey has to be a homicidal maniac now.” And as his gimmick (and indeed look) is overtly silly in a way nothing else in the Nolan films is, the decision to literally leave the best villain in the series hanging to make the film about one that doesn’t really work lets all the steam out of the film. The Joker represents an intensely generative aporia, but the film stubbornly fails to generate anything beyond a posthumous Oscar for Heath Ledger.

But making something of your best incoherence is almost inherently beyond the reach of a film. Aporia’s value is not in its resolution. And anyway, The Dark Knight, which understands itself as a politely conservative film that defends the importance of mass surveillance when implemented by suitably benevolent overlords, was never going to pay off the possibilities of the Joker. Its failure is far more interesting than success could ever be.

Ranking

- The Dark Knight

- Batman Begins

November 13, 2017 @ 8:46 pm

Good stuff, but BATS ARE NOT RODENTS.

November 13, 2017 @ 8:54 pm

Sorry, my knowledge of the matter extends no further than Calvin and Hobbes, so all I know is that they’re not bugs.

November 14, 2017 @ 5:02 am

It’s a common misconception, born probably from the assumption they’re like flying mice (even Alice says “There are no mice in the air, I’m afraid, but you might catch a bat, and that’s very much like a mouse, you know. But do cats eat bats, I wonder?”), but they’re technically in the order Chiroptera (“hand-wing”, referring to the fact they are the only mammals capable of true flight).

November 13, 2017 @ 9:46 pm

No, contemporary scholarship points to them being bugs…

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-SfGpcFa2-70/TWRt528UkJI/AAAAAAAAAEk/zlMGLCaGXuo/s1600/bats1b.jpg

November 13, 2017 @ 9:47 pm

Ah, damnit, Phil’s reply appeared to me immediately after I posted this…

November 14, 2017 @ 5:25 am

It’s the most overrated movie of the past 20 years, so it getting something of a kicking for it’s terrible neocon politics is honestly a breath fresh of air.

“Yes, Ledger’s schlubby maniac was an easier fit for a certain strain of geek masculinity than the more overtly queer portrayals that came before him.”

Jack Nicholson and Mark Hamill’s Jokers aren’t consider masculine? Really the only version of The Joker comes across as genuinely queer is Frank Miller’s terrible homophobic take on him in The Dark Knight Returns.

November 14, 2017 @ 5:49 am

This seems an appropriate time to hat-tip Jay Edidin, who gave a talk about the Joker and queerness at a University of Florida conference years ago with the delightful title “The Joker Wears Purple,” which was where I got that claim in my head. It was alas a decade ago, and so I remember his conclusion better than the details of his argument, but I think the title frankly already makes a strong case. He’s a thin, rakish man in makeup and a purple suit that exists in contrast to chiseled block of heteronormative masculinity.

November 14, 2017 @ 8:51 pm

This Joker style has his most important speech whilst dressed as a nurse.

If you read into that, chaos becomes the most chaotic when gender norms are destroyed, so it makes any queerness deeply problematic, but it’s style there, even in Ledger

November 14, 2017 @ 9:49 pm

I’ve read the Batman/Joker relationship in The Killing Joke as queer

” It is an 80s comic book view in which the Joker represents what happens when queerness is allowed free reign, Batman when it is closeted. They are both extreme reactions to a comic book world where queerness is defined as deviancy, and as such deviant behavior is the only way to express the queerness underlying their relationship. Any chance to express intimacy outside of those confines is engulfed in silence, and it is by seeking out these silences in the text (or how sound and silence interact) that this special bond between them is demarcated.”

November 14, 2017 @ 11:07 pm

oops, I forgot the actual link: https://themiddlespaces.com/2016/07/26/the-queer-silence-of-tkj/

November 14, 2017 @ 5:44 am

The Dark Knight is, perhaps shockingly, a movie I have a lot of experience with and thoughts about, and I’m really glad Phil and I seem to come to roughly the same conclusions about it.

Here’s my thing with The Dark Knight. I saw it as someone whose previous experience with Batman was the Saturday morning cartoon show, the Burton/Schumacher movies and Scooby-Doo. I saw it not having seen Batman Begins, because it was getting talked up by absolutely everyone all throughout 2008 (even, IIRC, before Heath Ledger died) as one of the best movies ever, and the best superhero movie of all time. I saw it because it was supposed to be good and I knew who Batman was, but not because I had any real investment in him or superhero media.

In that context, The Dark Knight was a very revealing experience. Going in knowing nothing about the first movie (though I maintain it works wonderfully completely in isolation, and, given the rest of its “trilogy”, this is probably the only way it can work in a productive and beneficial way). Because, as Phil points out, The Joker is astonishingly cogent and the film never really gets to the point of actually showing him to be wrong or refuting any of his arguments.

In fact, I’ll take it one further. The film, taken in a vacuum, gives The Joker the moral high ground for an alarming percentage of its runtime. And it ends on what I read, at the time, as a total indictment of the concept of Batman and the charismatic authoritarian hero archetype he stands for (not the ferry scene, which I’ll get back to, but the fight with Two-Face: I never thought we weren’t supposed to sympathize utterly with him or feel that Batman in any way hadn’t been completely in the wrong throughout the wrong the whole movie). Considering I spent most of the movie finding myself in complete agreement with The Joker, watching this movie was an experience that was equal parts sobering and clarifying (the obvious mass-murdering sadism stuff I just brushed aside as necessary conceits of the genre and didn’t give it any further thought than that: I read The Joker more as a philosophical fiction character and paid more attention to what he said than what he did so that didn’t really bother me, apart from a brief stint of feeling society must view me as a hated villain because of my beliefs).

I would actually go so far to call The Dark Knight an important milestone in my coming to terms with my own politics, even if the message I took from it was, in hindsight, probably the exact opposite of the one I was “supposed” to (I have far right relatives, indeed close relatives, who walked away from The Dark Knight saying the movie shows that “there is Evil, and Evil Needs To Be Fought”, which probably says it all). I think that’s where a lot of The Joker’s popularity comes from: He gave a huge, populist voice to concerns and views a lot of people would never have dared to allow themselves to entertain before, and it gave them a lot of ground…Even if some of those people took their lessons in an indefensibly destructive and hurtful direction.

And in that sense, the climax is a total letdown for sure. Even back then I left the drive-through thinking the film dropped the ball there. I kept thinking the boat scene made no real sense, but if it had to be there the civilians should have been the ones to pull the trigger on the convicts, while those on the prison ship should have been looking for a peaceful resolution. That would have proved the Joker’s point that “When the chips are down, these, ah, ‘civilized people’? They’ll eat each other”.

I could never figure out why the movie left it like that, especially as it seemed so much like it was setting Batman up to take the fall from the get-go: It always seemed to me that this was a proper “deconstruction”: A role-reversal where our “heroes” turn out to have been villains in disguise all along (as for The Joker dropping out of the narrative in favour of Two-Face, I can forgive that a bit more considering Heath Ledger’s death was so unexpected. The Joker was always intended to be a reoccurring character in the Nolan series and would have played a big part in the third film, and indeed any hypothetical subsequent Nolan Batman movies, had Ledger lived. Naturally he wouldn’t get closure here). Of course, once The Dark Knight Rises came out it became abundantly clear that proving The Joker right was never something Nolan was ever seriously invested in.

But, y’know, aren’t redemptive readngs one of the things we’re supposed to be doing here? If a text can be mobilized for revolutionary good, shouldn’t we try to make it if we can? After all, we need all the tools and help we can get at this point.

November 14, 2017 @ 5:57 am

To rephrase it a bit in terms of Phil’s reading of Man of Steel as being a movie where “ordinary people’s lives are upended when the Old Gods fight”, I guess you could say I read The Joker in this movie as a kind of cosmic trickster god who operates outside the code of human morality in ways that are horrific, but in doing so still teaches us valuable lessons we need to learn.

November 14, 2017 @ 6:47 am

“I could never figure out why the movie left it like that, especially as it seemed so much like it was setting Batman up to take the fall from the get-go: It always seemed to me that this was a proper “deconstruction”: A role-reversal where our “heroes” turn out to have been villains in disguise all along…

Of course, once The Dark Knight Rises came out it became abundantly clear that proving The Joker right was never something Nolan was ever seriously invested in.”

And that is one of the many reasons why I think Batman Returns is the best Batman if not super hero film because unlike Nolan, Tim Burton’s sympathies clearly lie with The Penguin and Catwoman and even Batman if forced to concede that he doesn’t have much of a moral high-ground over them in the end.

November 15, 2017 @ 6:05 pm

Perhaps fittingly given Phil’s read on Man of Steel, that’s essentially Grant Morrison’s conception of the Joker.

November 14, 2017 @ 3:07 pm

When you say “the Saturday morning cartoon show,” which one do you mean? An incarnation of The Super Friends, the DCAU version, or the 1977-ish Filmation series with Bat-Mite in?

November 14, 2017 @ 7:57 pm

The Super Friends and Batman the Animated Series both, actually.

November 14, 2017 @ 3:53 pm

I should note that this is literally the same argument Mikey Neumann makes in his redemptive reading of the film, right down to siding with the Joker as the film’s protagonist. (Though his argument to make the ferry scene work is a bit weak compared to the rest of the video.)

November 14, 2017 @ 7:59 pm

Well, it’s nice I’m not the only one who seemed to think so then!

November 14, 2017 @ 6:37 am

Speaking of The Dark Knight, and because this happens to intersect with a variety of my areas of expertise, and also to plug the good Liam Robertson, here’s a fascinating post-mortem of the movie’s aborted video game adaptation:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XTCayY8FDT0&index=21&list=PLE51D8DC24EBCBFA5

Liam has also done historical investigation into many other aspects of DC’s numerous failed attempts at a cinematic universe and other ventures as they pertain to video games. should you be interested:

Superman, by Factor 5 Inc:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qBeSUzmG43g&list=PLE51D8DC24EBCBFA5&index=19

Watchmen, by Bottle Rocket Entertainment

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ki4pwvRjlcE&list=PLE51D8DC24EBCBFA5&index=8

The Flash, by Bottle Rocket Entertainment

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-fGs1QcUWsg&list=PLE51D8DC24EBCBFA5&index=7

Justice League, by Double Helix games:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ypneUBO_8Y0&list=PLE51D8DC24EBCBFA5&index=1

November 14, 2017 @ 10:13 am

An excellent essay. Thank you, it gave me a lot to think about.

You’re spot-on about the Joker being a leftist villain in the same way that Voldemort is a fascist villain – I can’t believe I never realized that. He even fits a certain right-wing stereotype about the “lefties”. He’s a man who was hurt and traumatized – and who wears his ugly scars out in the open, obsesses about them, keeps telling everyone about them and uses his trauma to justify his “insufferable” behaviour. A proper hero, like Batman, supresses his pain and sublimates it into a powerful hunger for vengeance upon all criminals – substitutes of those who hurt him. A proper hero understands that the problem of violence can only be solved by more violence. Someone who keeps talking about his pain must be a villain.

And of course the Joker’s trauma is made up, existing in multiple contradictory versions ranging from parental abuse to self-inflicted pain born out of love. Because to really show him as a victim of abuse would mean taking his trauma seriously. If the Joker were really hurt, like Bruce Wayne was, they could, God forbid, bond over their traumatic experiences. Ask uncomfortable questions about the world that hurt them both so much. But no, the Joker is just crazy. And in Batman’s world, we lock these freaks up in the Arkham Asylum. The only ones who need psychological/psychiatric help are those who deserve to be in prison.

This version of Joker reminds me of both Rorschach and the Comedian from “Watchmen”. A nihilistic agent of chaos who considers the world he lives in “a bad joke”. The name he chose, it’s like a promise he made. To laugh at the world, to show everyone the absurdity of it. To make people question it. The key to comedy is surprise. And if I can be surprised, it means there is something true about the world that I never considered. It means there is a crack in my worldview through which other worldviews can be seen. No wonder it scares the hell out of people like Batman and Gordon.

November 14, 2017 @ 10:32 am

It just occured to me that Harvey Two-Face fits the trauma angle as well. He’s created by the Joker by way of emotional and physical pain. “One bad day” indeed. But this pain can only be transformative in a negative sense. That’s what his refusal to suppress his pain with medications means. If you acknowledge and feel the pain, it only deforms you. Harvey’s inner dualism, exposed by the Joker, is then further fueled in a hospital, by someone dressed as a nurse. Those who want to help you to deal with pain are actually enemies with ulterior motives. Of course they are.

And so Harvey chooses the wrong path. He chooses to leave his face (his trauma) exposed instead of hiding it behind a mask. He chooses to listen to both sides of his personality instead of supressing one and keeping it in check like he did before. And he chooses to accept the random, chaotic nature of the world instead of trying to police it. The film’s ending tells us clearly what the right path was. It was to turn dead Harvey’s head to the side so that only his good half can be seen. And it was to close his casket and put up his pictures so that everyone could see that this man was never hurt.

November 15, 2017 @ 10:20 am

Fair points – although it’d be a stretch to call either Rorschach or the Comedian “leftist”.

November 15, 2017 @ 2:20 pm

You’re right, of course. The Joker mostly reminds me of them on aesthetic/characterological grounds.

November 14, 2017 @ 1:51 pm

This structure – of Batman’s villains being ostensibly correct leftists who the film can barely manage to keep a conservative lid on – is really going to come to a head in the next one, huh?

As an aside, I’ve got a bit in an upcoming video essay on Suicide Squad (and it seems I’ve got more time for Leto’s Business Class Joker than you) about how Ledger’s line at the end – “we’re going to be doing this forever, you and I” or w/e, is the ultimate defeat of Bale’s Batman, who is opposed to any kind of progress or transformation in society whatsoever. Even if he keeps fighting the Joker forever, stomps down on every point of rupture, eventually society will change.

November 14, 2017 @ 9:57 pm

Everything the Joker predicts comes true. Everything he started, Bane finishes. Kills the mayor, isolates the city, destroys the society. Those civilized people eat each other.

November 15, 2017 @ 3:41 am

Good essay. It provokes some thoughts.

The Joker is a particularly Nolanesque villain. From his earliest films, Nolan has been obsessed with structure. His films always feel “architected” rather than “drawn” or “told”. My main beef with his work is his prioritisation of structure over character in his plots.

The Joker represents a particular threat, a particular fear in Nolan world: a force whose goal is to provoke the collapse of structures. Nothing could be worse. Except that the Joker is very Nolanesque is his anti-Nolanism. Contrary to his speech in the hospital, the Joker is a schemer, a creator of elaborate structural plots. The opening bank heist turns on each crime playing his role exactly as scripted – even to the point of standing in the right place to be hit by a bus. For someone who proclaims chaos & decries plans, the Joker is awfully addicted to planning. In his painstakingly choreographed violence, the Joker resembles nothing so much as a director of blockbuster action movies.

November 15, 2017 @ 4:57 am

Another thought concerns when this movie came out. It was in production in 2006-2007. This is a fair way post-9/11. It is also well into the Iraq War and post-Katrina. It is just before the Financial Crisis. In some senses, it is out of joint with the zeitgeist.

The movie proposes Batman as authoritarian. But a competent authoritarian facing an anarchic force. His mass surveillance system does its job and it is destroyed at the end of the movie.

Our world is not behaving in such a neat fashion. There are authoritarians but they are far from competent. Lightning wars turn into quagmires. Storm-drenched cities are flooded wrecks for weeks. George W Bush’s approval ratings are on the slide for most of his presidency (with bumps for the Iraq invasion, the 2004 election, and a massive one for 9/11) but it’s after Batman Begins that they fall below 50% (not that I am suggesting any causation here). Surveillance drags on and morphs beyond simply the state monitoring people’s phone calls and emails.

And I’m not even going to touch things like this: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/column-is-barack-obama-our-harvey-dent/

November 15, 2017 @ 5:13 am

Another: What kind of anarchist is the Joker?

(N.B. I am not an expert on anarchist thought). The Joker’s primary antagonist is not really the state. He fights as much with criminals as he does policemen. He has no utopian vision of the future nor any real interest in how humans interact. What he offers is kind of negative of Hobbes. The state of nature that Hobbes abhors, he looks on and says “that seems pretty cool”. He’s not interested in amassing wealth or the normal trappings of power. He instead seems driven by the need to escape an intense boredom. The chaos is to be created and nurtured and supported because the alternative is so… what? Insipid? Threatening? It’s hard to know because he’s not supposed to be a character with conventional motivations, with an origin story. He is a fundamental force of the narrative. He’s not political so much as ontological.

Incidentally, I don’t think that audiences were ready in 2008 to go along with the Joker’s premise that that human beings are one hair’s breadth away from chaos. I wonder if they are now.

November 16, 2017 @ 9:45 am

I don’t think people are ever going to be ready to accept that. It’s a very scary thought, and not just for the conservatists.

Good catch about the Joker being an ontological force of chaos rather than a character. If I had to assign any actual character motivations to him, I think I’d go with the need to be proven right. He’s like those deeply cynical people who look at anyone less cynical than them and say “you’ll come to agree with me, just live a little longer”. The Joker figured out the truth about humanity and now humanity must prove him right, even if he’s not. (But then again, like Phil said, the movie doesn’t really manage to prove him wrong).

November 16, 2017 @ 11:25 am

Which makes him sound a bit like an internet troll. A characterization that has some truth. You could imagine him doing something like GamerGate.

This Joker is deeply cynical about human nature. But he has no concept of human imagination or intimacy. He’s… lacking. Batman can’t really oppose that because he doesn’t either.

November 16, 2017 @ 9:55 am

Ooh, a very good point! It’s like Nolan wanted to create an embodiment of chaos… but the best he could come up with was “a violent schemer”. A surprising and, frankly, cute lack of imagination.

I wonder if unleashing a true force of chaos upon this movie would render Batman powerless and ineffective. If his enemy really doesn’t have a plan then how can he plan against him? If the violence that killed his parents cannot be eliminated by military gear and surveillance cameras, why even bother to fight crime?

November 15, 2017 @ 7:43 am

An interesting observation about actually-leftist villainy. Makes me think about left-labeled villains too: It seems to me that the common pattern, when someone we might broadly call “center or right” wants to write a leftist villain, is basically to write a fascist and pin a red star on them.

There’s some historical grounding for this, of course: you could legitimately frame the Bolsheviks this way if your heroes are meant to be anarchists in the vein of Makhno or Durruti, for instance. But I can’t escape the suspicion that most of the time, the sort of people who write like that actually think that the NSDAP was a socialist party (“That’s what the S is for, duh, and everybody knows Nazis never lie about anything”), or that Orwell and McCarthy would have gotten along since they both hated Stalinism.

Probably mostly it’s just laziness, though: the fascist stuff is just “what villains do,” so if we want a commie or anarchist villain we’ll put some commie/anarchist words in his mouth and then have him do “what villains do.”

November 15, 2017 @ 11:50 am

From the point of view of anyone less amoral than the Joker, isn’t there a certain contradiction, or at least serious tension, between endorsing anarchism and rejecting the upbeat resolution of the bomb situation as tritely unrealistic? (Granted that this article doesn’t quite do that, rejecting it as contradicting the world as represented in these films rather than the world as it is, but still.) Anarchism depends on a highly optimistic view of human nature. If it’s only the veneer of social order that keeps people from eating each other, best keep that veneer laid on good and thick.

That tension can be resolved in principle by taking a Rousseau-style position that it’s the very fact of being civilised that makes people bad. But that would not do away with the practical problem that if people at present are bad, however they came to be so, toppling the social order would still lead to a bloodbath, nor the likelihood that, as soon as the frenzy calmed down a little, a population accustomed to order would promptly start building it anew, in a more basic and brutal form than the one that went before.

November 15, 2017 @ 6:41 pm

Agree. The Joker doesn’t really offer a coherent political view of the world (but then he’s a cartoon character who dresses a clown fighting another character who dresses as a bat). And the film isn’t interested in exploring the politics, morality or implications of different forms of anarchism (David Goyer was the writer rather Ursula Le Guin).

November 16, 2017 @ 11:33 am

Not necessarily “highly optimistic,” but you’re basically right. (Alan Moore has described anarchism as “the only political system that has ever worked,” and he’s pretty much correct: It turns out that “do what I say because I have a gun” doesn’t actually function well for much longer than the length of the average bank robbery. At some point you need to build consensus and start behaving like sensible anarchists at least within your group, even if inter-group relationships are still at gunpoint.)

I don’t think the problem is the outcome of the boat set-piece. The problems are first, that it’s unprecedented: maybe this is how people really are (if you’re an optimist), but it’s a sudden intrusion of real people into a movie that hasn’t had them until now. Second, it’s just not good movie. It’s lazy, we don’t care about the characters (Business Guy on Business Trip, The Warden, and Big Prisoner #1, I think are their given names), and the writing doesn’t earn much either. Honestly the only bit that really sticks in my head is the prisoner playing to the warden’s baser desires. Those lines worked, the rest was just okay.

November 17, 2017 @ 12:54 pm

Obviously we’re verging on a much bigger debate here, but that does seem a bit reductive (though that may just be the product of summarising complex ideas in a few sentences).

Power ultimately rooted in violence operates through a profusion of different material, psychological and cultural mechanisms other than explicit threat, and even explicit threat usually only requires the threatener to take action occasionally. Consensus-building within a group typically takes place in ways much inflected by gradations of hierarchy and authority – everyone getting a say does not imply everyone’s say having equal impact. The implementation of consensus decisions commonly calls forth enforcement mechanisms (which often have a way of developing their own momentum once they get going). And of course interactions between groups of one sort or another account for an extremely large proportion of the violence, coercion, exploitation and general power-imbalance in human history.

So characterising all political relations that aren’t one person compelling one or more others by the active, present exercise of violence as essentially anarchistic seems like stretching the definition of the concept into uselessness. But I grant that that may be a caricature of what you’re actually saying.