An Unusually Determined Suicide (Book Three, Part 24: Bible John, Third World War)

Previously in Last War in Albion: Grant Morrison penned a final work in the British market during this boom, a piece called Bible John in a magazine called Crisis.

The complex phenomenon we project. That alone is real. The actual killer’s gone, unglimpsed, might as well have not been there at all. There never was a Jack the Ripper. Marie Kelly was just an unusually determined suicide. Why don’t we leave it there? -Alan Moore, From Hell

The eponymous Bible John was a serial killer who operated in Glasgow in the late 1960s. His pattern was to pick up young women at the Barrowland Ballroom—all three victims were menstruating at the time of their deaths—beat them, and strangle them to death with their own tights. In the wake of the third killing the victim’s sister, who had shared a cab with both her and the killer, recounted him giving his name as “John” and quoting Bible verses on the drive, hence the nickname. A massive investigation followed, including the first time in Scotland that media published a composite portrait, but the murders remained unsolved.

Morrison’s comic is as its subtitle describes it—a meditation and history of the killings in which Morrison conducts their own investigation as a narrative over their former Fauves bandmate Daniel Vallely’s expressionist best Bill Sienkiewicz/Dave McKean imitation. This narration is intense and psychogeographic in its approach. “The murder sites can still be visited,” one early section begins. “They include not only the geographical locations but also the graveyard acres of newsprint, of drawings, of photographs. Family snapshots with the grain enlarged. Black and white pointilist portraits, arranged in rows. Let’s go down there. Looking for clues. This is dead ground where even the air seems stunned into amnesiac silence. Lanes diminish into forced perspectives.”

It is impossible to read this and not to think of Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell, which examined the Jack the Ripper murders from a similarly informed perspective, and which had begun publication in 1988, rendering it a surefire influence on Bible John. Indeed, Morrison discussed the comic in a Drivel column in November of 1990, noting its “unacknowledged debt to the subtext and subject matter of Iain Sinclair” while calling it “as fine a piece of narrative construction as one is likely to see in a comic book” in the course of a larger (and tremendously insightful) argument that obsessions with plagiarism are “based on the bourgeois concept of art as a commodity which is the sole privilege of an educated cultural elite.” Though of course given Drivel’s performative excesses it’s worth nothing that this argument came four months after their snark about Moore and Superfolks and four months before the beginning of Bible John, which contains no acknowledgment of the debt its own “wander around murder sites and report on their psychic energy” approach owes to Sinclair.

Ultimately, however, this is an easy comparison to overstate. From Hell was in many ways a successor to Watchmen, using a tight nine-panel grid and no narration or caption boxes until the ending chapters (published years after Bible John), depicting the Ripper murders directly instead of talking about them from a historical vantage point. The narrative voice of Bible John has more in common with that of Moore’s spoken word magical performances, but the first of those took place in 1994, three years after Bible John. (Could Moore have been influenced by Bible John? Perhaps, although ultimately Moore’s style is best understood as a refinement of the style he’d already developed in Marvelman and Swamp Thing and refined in The Mirror of Love and Brought to Light. In the end, as always mere influence is by some margin the most banal front upon which the War is waged.)

A more useful way of understanding Bible John is, perhaps, to view it as a successor to Arkham Asylum. Certainly it has many thematic elements in common, especially late in the strip when it begins making allusions to the Moon Tarot card. And with Vallely doing the sort of abstract and collage-based work that McKean was known for there’s a fair case to be made that the strip is Morrison taking another bite at the apple, taking the symbolism they’d tried to weave into a Batman comic and constructing a very different sort of labyrinth with it, making better use of their artist’s style this time.

But Bible John is more than just a set of influences, a fact that becomes exceedingly clear in its fifth part, when Morrison relates how they and Vallely engaged in a seance in an attempt to solve the Bible John murders. (This novel approach to writing nonfiction might have been inspired by Donald Ault’s essay the previous year “Where’s Poppa? or, The Defeminization of Blake’s ‘Little Black Boy’,” which ended with Ault recounts a dream in which he “showed this manuscript to Blake, who told me that he was ‘not uncomfortable’ with my reading of ‘The Little Black Boy,’” although obvious precedents exist in Blake’s own work, most obviously in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell when he archly describes dining with the Prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel and asking them about their assertion that God spoke to them, quoting Isaiah as saying, “I saw no God, nor heard any, in a finite organical perception; but my senses discovered the infinite in every thing, and as I was then perswaded and remain confirm’d: that the voice of honest indignation is the voice of God, I cared not for consequences but wrote.”) Over several pages Morrison recounts their dialogue with an unknown spirit who claims to know the identity of Bible John. The spirit’s clues are alternately cryptic and vague—many of the details line up with what would eventually become the prevailing theory of Bible John, which is that his were the first crimes of serial killer Peter Tobin, but just as many are impossible to reconcile.

With this conclusion largely unavailable to Morrison (although it’s striking that two of the three murders Tobin would eventually be convicted of, those of Vicky Hamilton and Dinah McNicol, came almost precisely Morrison’s strip was beginning and ending in Crisis—surely a coincidence, and yet it’s impossible not to think about the tendency of serial killers to follow news about their crimes and wonder if he knew of Bible John, and if it awoke old desires—although at that point one might as well credit Morrison with magically solving the case, given that Tobin was actually convicted for those two murders), the strip instead ends on a note of ambiguity and unknowability—much the same sort of point Moore would reach in “Dance of the Gull Catchers” after all was said and done in From Hell. It’s an elliptical, strange ending for the most overtly and self-consciously magical work in the War to date, and a fine capstone for the strange but largely wonderful book that was Crisis.

Crisis was an anthology with many good comics across its run, but for the most part its flagship strip was Third World War, created by Pat Mills and original Judge Dredd artist Caros Ezquerra. Mills had in effect been the Alan Moore of the previous generation of British writers, overseeing the revitalization of British boys comics from their painfully staid roots of interchangeable jingoism into something far spikier and angrier. His triumphs in this regard are numerous. Not everything that Mills wrote was so accomplished, of course; plenty of his work was unremarkable beyond his capacity for generating a frisson of naughtiness. Nevertheless, Mills reinvigorated British comics, leading the revolution that turned them into the sort of thing that Alan Moore and Grant Morrison could emerge from.

With Third World War he crafted a late masterpiece, taking the attitudes and approaches that he pioneered in his imperial phase and applying them directly to the political concerns of the present day via a near-future setting. The timeline in the first issue made its position clear: after an opening quote from Brazilian labor activist and future President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva declaring that “the Third World War has already started… a silent war. Not for that reason any the less sinister. This war is tearing down Brazil, Latin America, and practically all the third world. Instead of soldiers dying there are children. Instead of millions of wounded there are millions of unemployed. Instead of destruction of bridges there is the tearing down of factories, schools, hospitals, and entire economies,” Mills includes a timeline starting from the end of the Second World War in 1945, declaring the third to have broken out in 1946 with armed rebellions in China, Palestine, and Vietnam. After an entry describing the entire post-war period as “Over 150 regional conflicts across the globe resulting in over 300 million deaths. Rise of the multinational through corporate mergers and takeovers… multinational companies control approximately 90% of the world’s trade in food, minerals, and oil.” A brief future history follows, covering the outbreak of a wealth of populist uprisings in 1996, the formation of FREEAID, a corporate subsidized “international development” agency with compulsory youth conscription, Mills offers a magnificently arch account of where his strip takes place: “2000 AD: Now.”

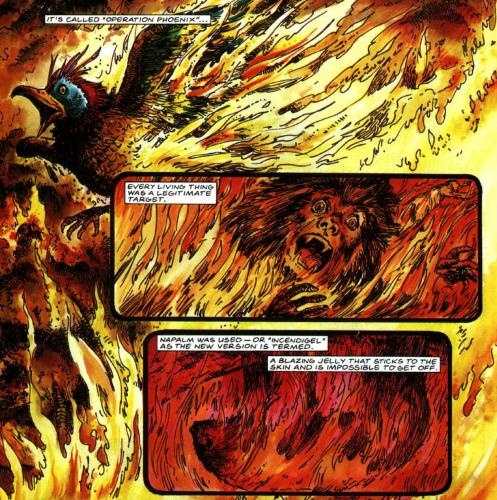

Third World War follows Eve, a Black woman in London who is drafted into FREEAID and responds by attempting suicide. She fails, both ensuring the strip runs for more than three pages and landing her in a misfit battalion aiming to protect the people of Latin America from “subversives” and win over “hearts and mind” as FREEAID liberates Honduras on behalf of the Multifoods Corporation. In practice what this means is moving the entire populations of villages into the “New Prosperity Zone,” which is to say forcing people from their homes at gunpoint and into concentration camps. In the first arc, once this is accomplished Mills and Ezquerra offer a two page sequence of the abandoned village being napalmed to the ground “to deny food to the guerillas,” with a page of monkeys, tree frogs, and tropical birds in flames.

Third World War, in other words, was a comic that happily (or at least angrily) traded subtlety for sheer and relentlessly brutal clarity. This was propaganda in comics form, with issues often turning into straight-up lectures of the sort that would eventually come to characterize much of Alan Moore’s late work. Indeed, later installments often came with attached reading lists, encouraging readers to check out things like William Blum’s The CIA: A Forgotten History and The Autobiography of Malcolm X. The comic, however, never loses sight of Mills’s familiar sense of bitter irony, caching its unapologetic moralizing in a sense of morbid humor. (“Oh dear,” muses a commanding officer. “How do you explain economic theory to a simple peasant?” when a village leader points out that his village is doing perfectly well growing food for themselves instead of growing food to export so they can buy food.)

Third World War ran for fourteen installments before moving into Book Two in Crisis #15. This issue saw a slight rework to the format, with the idea of repackaging stories for the American market dropped in favor of a more traditional anthology format. It also saw a major shift to Third World War, which abandoned its FREEAID plot in favor having Eve return to Britain and join the Black African Defense Squad, a militant organization seeking to reestablish Brixton as New Azania, a black nationalist state with matriarchal rule. For this arc, as the magazine explains, “Pat realized that black issues would play an important role in the saga, and that—since these events were outside his own sphere of experiences—he needed to find a suitable black co-writer,” which ended up being Alan Mitchell, shop manager for Acme Press’s Brixton store. Ezquerra left the strip early in this phase, replaced by a rotating lineup of Duncan Fegredo, Sean Phillips, and John Hicklenton, whose nightmarish depictions of psychotic police chief obsessed with Eve proved a highlight of the comic. (How Hicklenton, who had previously illustrated Nemesis the Warlock in 2000 AD and did Future Shocks with both Gaiman and Morrison, and was one of the most distinctive artists of the period, never got picked up to do a horror book in the early days of Vertigo is a genuine and frankly depressing mystery.)

This second phase lost some of the aggressive clarity that marked the first fourteen two-parters, with endlessly rotating artists and a spiralling sense of scope leading to the sort of drift that long-running strips often suffer. Nevertheless it was never anything short of an arresting and chilling denunciation of the world that was coming into being—a burst of focused anger that consistently stood as one of the highlights of the late 80s/early 90s renaissance.

The start of Book Two of Third World War coincided with a general reinvention of Crisis—a phase during which it was without a doubt the best British comics magazine on the stands. While Third World War remained at fourteen pages an issue, the other feature in the first stretch of Crisis, John Smith and Jim Baikie’s New Statesmen, was replaced by two stories. Sticky Fingers by Myra Hancock and David Hine, a slice of life story told in six-page chunks, and Troubled Souls by Garth Ennis and John McCrea. [continued]