Blow Away (For Bill)

This blog post was brought to you by 22 backers on Patreon. If you’d like to read Dreams of Orgonon early and have access to my exclusive  writing on other subjects, please consider pitching in. I’ve recently added a $10-per-post tier to the Patreon for those who’d like me to proofread their writing. If that interests you, we can talk. Any money at all significantly helps out this minimum-wage-working trans writer. Thanks for your support.

writing on other subjects, please consider pitching in. I’ve recently added a $10-per-post tier to the Patreon for those who’d like me to proofread their writing. If that interests you, we can talk. Any money at all significantly helps out this minimum-wage-working trans writer. Thanks for your support.

After the Tour of Life wrapped, Bush stayed out of the studio for a few months, giving herself room to breathe in between albums. By August, she’d gone to Abbey Road with engineer Jon Kelly to mix the EP On Stage, a collection of four live recordings from her tour and the only EP she’s ever produced herself (other Bush Eps have been promotional efforts by EMI). Shortly afterwards, Bush and Kelly moved to London AIR Studios to record Never for Ever. The initial 3-and-a-half-month-long sessions that followed heralded the masters of “Violin,” “Egypt,” “The Wedding List,” and “Blow Away.” Given that “Violin” dates from around 1976 and Bush wrote “Egypt” for her tour, “Blow Away” is the initial Never for Ever song, and it’s more beholden to her tour than most of the album. It’s the most directly autobiographical song, drawing as it does from both personal acquaintances of Bush and music history. Like “Violin” and “Egypt,” “Blow Away” made its debut onstage, when Bush performed it for the 75th anniversary of the London Symphony Orchestra in November of 1979, when Bush put in an appearance at the Royal Albert Hall. The song’s structure was nailed down pretty early on, as its demo is more or less a stripped down version of the master recording. It’s not clear exactly when Bush wrote “Blow Away,” as it could have been written on the road or during the summer between tour and album, but it’s definitely marks a newfound clarity in Bush’s songwriting, which become sharper, boasting more memorable hooks and keen structures than Lionheart’s more unruly songs.

Bush’s newfound confidence as a songwriter was accompanied by her newfound lack of certainty about the world. The songs of Never for Ever ask bigger questions than her first two albums do. “Blow Away” is one of Bush’s many songs to deal with death, and issues of consciousness. It’s an ethereal dirge, sung “For Bill,” referring to Bush’s engineer Bill Duffield, who was accidentally killed on the first night of her tour in an especially grim bout of party-pooping. It’s rare for Bush to sing about her personal life and friends, (we’re still far away from “Moments of Pleasure”) but there’s a whole song on her tertiary LP dedicated to an engineer she knew for a probably rather short period of time. Bush’s renowned generosity towards her collaborators extends to everyone on her team, as her charity concert for Duffield shows. Her use of “we” instead of “I” when discussing the making of her albums pretty much says it all. She’s essentially still in the KT Bush Band, where everyone is a member of a group and of equal importance. Still, “Blow Away” isn’t a character study of Duffield, nor does it exploit a tragedy for sentimental purposes. It carefully positions his death as a tragedy in the vein of musical giants, casualties of musician life and its dangers.

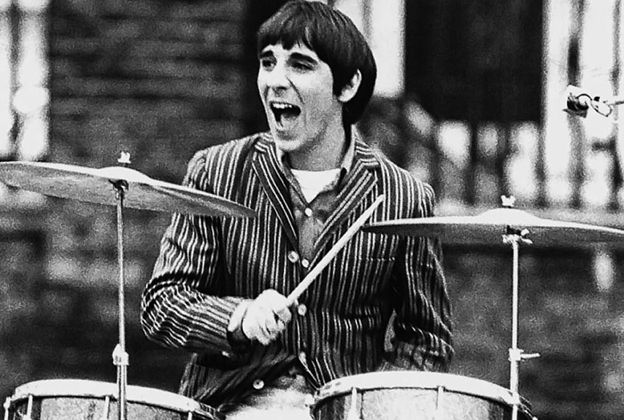

Duffield is directly referenced once, in a conversation about the afterlife. The engineer suggests that people who’ve died but come back to life go to a special room in the afterlife where they meet a group of dead famous musicians. The second chorus lists the musicians present: Minnie Riperton, Keith Moon, Sid Vicious, Buddy Holly, and Sandy Denny. One major point in common among these artists is that all of them died tragically young, with Moon being the oldest of them at 32. While not all of these artists’ deaths were cautionary tales by the excesses or doom of celebrity (Riperton’s death came from breast cancer rather than a plane crash or a heroin overdose), they were all recent deaths reinforcing the story of the foibles of celebrity.

While we’re dealing with mortality, we have to deal with the jaw-dropping fact that Bush quotes Othello in this song. “Put out the light/then put out the light” is her Shakespeare line of choice. In the context of the song, the quote is the opener for the meandering third verse. The lines that follow never quite cohere into a strong verse (“dust to dust/blow to blow”), but it’s worth thinking about why Bush copped this Othello quote. The line comes from Othello’s ending, in which Othello is preparing to murder his wife Desdemona in her sleep, falsely believing her to be an adultress. The line is a Shakespearean double-entendre, referring both to snuffing out Desdemona’s life and to her pale skin (the race politics in Othello are among the most fascinating and analyzed in all of literature). The actual meaning of this line is, of course, lost when deprived on context. Yet it’s an interesting line for Bush to lean on. It frames the deaths of these popular stars — and Sid Vicious — as classical tragedies, the downfall of great artistic figures. It risks being hagiographic, but at the same time there’s something compelling about the strangeness of this framing.

The use of Buddy Holly as a poster child for rock tragedy harkens back to another Seventies songs featuring his death, Don McLean’s “American Pie.” That paean to the fifties which has caused many boomers to explode phallic blood vessels is more grossly nostalgic than “Blow Away.” Tom Ewing has a great write-up of Madonna’s “American Pie” cover on Popular (which you frankly should read instead of wasting time on this blog), so I won’t discuss it in too much depth here, but suffice it to say that the song is a veritable tome of song references by a songwriter who can’t get over the music of his youth (Ewing hilariously mocks McLean’s unsubstle “Eight Miles High” namedrop). Ewing describes “American Pie” as “a theological dispute between Buddy Holly and Mick Jagger.” Holly is an ideological ploy for McLean’s rockist sectarianism. Little insight is offered into the workings of Fifties music. What McLean gives the listener is a nostalgia package: memory is what he trades on. In McLean’s mind, Altamont didn’t strike the killing blow to the Sixties dream: it was dead when it started. Mick Jagger ever getting on stage was the cardinal sin for “American Pie.” McLean’s use of “The Day the Music Died” isn’t a simple metaphor for the deaths of a few rock ‘n’ roll singers. In McLean’s view, it’s the point an entire tradition is co-opted and desecrated by these Lennon-McCartney whippersnappers.

Bush, of course, isn’t writing a song about the careers of Buddy Holly and the other deceased either. But “Blow Away” where differs from “American Pie” isn’t especially nostalgic — its points of sentiment were largely contemporary deaths. When Keith Moon overdosed, one of the biggest quartets in rock was partially dissolved. Punk discovered new proverbial dangers in Sid Vicious’ death. When the Seventies ended, a lot of assurance about how musicians lived and worked died with them. “Blow Away” can be read as a testament to this, chronicling the way popular music responds to the deaths of its idols. Framing the song as she does around a room where one can meet Minnie Riperton and Marc Bolan, she places deceased musicians in a paradise of their own. Certainly she’s lionizing these figures — which is maybe not a great move in a song namedropping alleged murderer Sid Vicious — but she’s engaging in ideas beyond “my generation of music is cooler than yours.” Think Bob Seger’s “Old Time Rock and Roll,” but for people who still get laid.

There are reasons for this. Unlike McLean, Bush is going to keep writing songs people care about. She’s still paving the way for the music of the Eighties. While “Blow Away” is one of the less synthy tracks on Never for Ever, it’s more ambient than some of the songs on Bush’s first two albums. The Martin Ford Orchestra’s strings gives the song space, and Bush’s piano playing often has moments of silence which let the song breathe. The actual rhythm of the song is minimal, lacking the urgency of more rock-inflected music. It’s almost New Age, but in a genuinely spiritual way.

So what does “Blow Away” think of the afterlife? Well, it clearly thinks there is one. The dead have souls in Bush’s music. Her universe is populated by spectres — “The Kick Inside” and “Hammer Horror” demonstrate that. “Blow Away” fills their slot on Never for Ever — the song for those beyond the grave. Yet “Blow Away” is more optimistic about their chances of a happy eternity. Consciousness may thrive after death, but Bush has finally liberated her deceased characters of their mortal woes. Part of this is a matter of taste: everyone knows Keith Moon is in hell, but in 1980 it wouldn’t have been politic to say it in a song. Yes, there’s reverence for these musicians in this song, but the nostalgia is alleviated by the thoughtful weirdness of the song. It’s not the most radical song on the album, but it’s assuring that Bush’s optimism for the power of artistic imagination extends beyond the grave.

Performed live on 18 November 1979 at Royal Albert Hall. Recorded September 1979 at London AIR Studios. Personnel: Kate Bush — vocals, piano. Preston Heyman — drums, percussion. Max Middleton — Fender Rhodes, string arrangement. Brian Bath — acoustic guitar. Martin Ford Orchestra — strings.