Clara Who: The Impossible Narrator

I was not as entranced with Series Nine as I’d hoped, but that may well be due to events in my own life and the kind of work that’s been on my plate this fall. I realize I haven’t written nearly as much about the show as I have in years past. So, this is to kind of rectify that, somewhat, and to encapsulate my thoughts on the series as a whole, and particularly in the context of Clara’s overall arc in the show.

I was not as entranced with Series Nine as I’d hoped, but that may well be due to events in my own life and the kind of work that’s been on my plate this fall. I realize I haven’t written nearly as much about the show as I have in years past. So, this is to kind of rectify that, somewhat, and to encapsulate my thoughts on the series as a whole, and particularly in the context of Clara’s overall arc in the show.

This is in large part inspired by a conversation on Tumblr the last day or two, where Caitlin (abossycontrolfreak) properly tore apart the problematic Claudia Boleyn’s objections to Clara in Series 7. Mind you, there are other dynamics in this interchange involving Claudia’s style of critique, which erases or belittles countering views, and this is really the least of my concerns; both Caitlin and Julia (tillthenexttimedoctor) have effectively addressed this already, imho. At the heart of the mistake, though, was the belief that Clara wasn’t properly characterized in Series 7. But I’ve seen this a lot. It has more to do with the storytelling than the stories themselves. And even more than that, it has to do with how we read stories.

So what I really want to talk about is the role Clara plays as a storyteller, as a narrator, and how that intersects with the narration of the show as a whole. It is no secret, of course, that the nature of storytelling is one of Moffat’s main themes in his tenure of running Doctor Who, made plain in the “We’re all stories in the end” speech at the end of The Big Bang. But as we’ll see, this is also something that occurs in RTD’s handling of the series; furthermore, Clara marks a significant departure from other “narrators” as far as Companions are concerned.

A Bit of Theory

Before I get into that, I do want to briefly discuss the kind of background I’m coming from when it comes to narratology. It’s a bit of a hodge-podge, really, from deconstruction, death of the author, close reading, and all that, but I always find myself returning to Story and Discourse by Seymour Chatman, who’s a fairly significant Structuralist. Not that I fully subscribe to his theories, just that I find them a useful framework to start with.

Like many structuralists, Chatman begins along the lines of Russian Formalism by distinguishing two aspects of narrative. The Russians used the terms “fabula” (the actual events of a narrative) and “syuzhet” (the organization of those events); Chatman uses “story” and “discourse,” but in a much broader sense, with “story” encompassing events, character, dialogue, setting (the “stuff” or “contents” of a narrative) and “discourse” including all the different ways the narrative is “told” – not just the organization of the text, but the narration of it as well. Cinematically, “discourse” would also include camera angles, cuts, lighting cues, the soundtrack, and things of that nature.

Like many structuralists, Chatman begins along the lines of Russian Formalism by distinguishing two aspects of narrative. The Russians used the terms “fabula” (the actual events of a narrative) and “syuzhet” (the organization of those events); Chatman uses “story” and “discourse,” but in a much broader sense, with “story” encompassing events, character, dialogue, setting (the “stuff” or “contents” of a narrative) and “discourse” including all the different ways the narrative is “told” – not just the organization of the text, but the narration of it as well. Cinematically, “discourse” would also include camera angles, cuts, lighting cues, the soundtrack, and things of that nature.

I actually find certain Impressionist paintings a really useful way to illustrate this difference. Here we have a couple of Claude Monet’s paintings from his Houses of Parliament series. One is at sunset, the other in the fog. The “story” here is simply that of the Houses of Parliament, the river, the sun and fog, the boatmen. But these paintings are more than that – the “discourse” is how Monet paints them, which is with a layer of abstraction – the rough paint strokes creating indistinct figures, and his use of color, create an effect that conveys not just a representation of the objects, but a revelation of them, an emotional response, a “sense” that isn’t concerned with how they appear “in reality” but how we receive them, even remember them, for memory is often hazy and imprecise. In other words, there’s a “narrator” here, implicitly, conveying a subjective truth as opposed to an “objective” one.

And in a sense I find such work more honest, because there’s always a subjective point of view. Attempts at “objectivism” are simply attempts to elide the point of view of the narrator. Which is important for understanding my relationship to Chatman’s theories of narration.

Chatman posits a storytelling model like this:

Real author —> [ Implied author –>(narrator)->(narratee)–> Implied reader ] —> Real reader

He goes on to describe how the “narrator/narratee” in this model is optional, reserved for characters who are storytellers/readers in their own right. I don’t particularly like this model. For one, it suggests the possibility of “non-narrated” stories, which goes back to the problems of the myth of objectivity. One of Chatman’s examples of a “non-narrated” story is a collection of letters or correspondence – the story that emerges isn’t being narrated, per se, as a story. But I disagree, but represents objective fact. However, simply the choice to collect the letters and put them in a certain order (even a strictly chronological order) betrays the intent to narrate, so I claim that that every “implied author” really is a narrator. Some acts of narration occur within a “story,” others within a “discourse,” but let’s not pretend there’s no narration. In this way, we can be clear whether the narration is “internal” or “external” to the story itself.

But even in this distinction there can be a blurring of the lines. Here we’ll turn to some basic concepts in literature. A story told in the first person, for example, is clearly an example of character-based narration. The story is limited entirely to that character’s voice and perceptions, and as such it can be easy to discern or anticipated a certain amount of unreliability. The third person omniscient, on the other hand, pretends something else entirely, having access to every character’s head, every setting (even those without characters), every period in time. Such a voice isn’t a part of the story, just the discourse. It’s a problematic POV, however, in that it purports to be unbiased and all knowing.

In between we have the third-person-limited (or “third-person-close”), where the purported “objectivity” is tied to the perspectives of one or more particular characters. Information is limited, but the trick is that this mode of storytelling allows the subjectivity on the part of the characters to influence the storytelling, without getting into the problem of first-person narration, which introduces the problem of the narratee (as the reader isn’t actually a part of the story, typically). In other words, third-person-close allows a degree of Impressionism.

For the purposes of the rest of this essay, I’ll be using the term “implied author” to refer to such narration that isn’t controlled by or reflective of the characters themselves, this “external” narration.

How All This Applies to Doctor Who

Obviously, cinematic texts have different issues regarding narration. A “first person” narrative in cinematic language would be like having the “camera” be a narrator on the visual channel, and voice-over narration on the audio. Which is terribly clunky. There are reasons we don’t see this kind of storytelling in cinema.

The other problem with cinema, though, is that the nature of the camera gives us the sense as readers that the story is being told “objectively” or even omnisciently. We are always at remove from character interiority – unlike the written word, cinema struggles to get inside the characters’ heads. It’s the biggest difference in the written and televised versions of Game of Thrones, for example.

But there is a way to cinematically to do “third-person-close,” which is to direct the story as if it were being competently directed or influenced by the characters themselves. In this mode of storytelling, the choices of the “discourse” reflect the characters. For example, consider the difference between the beginning of Rose and the beginning of Army of Ghosts. Rose begins with a montage of shots from Rose’s life, waking, working, eating, playing, and she seems to be having a good time, as far as we can tell from the discourse – the bright lighting, the gauzy lens, the basic color scheme, the jaunty music, the quick cuts. But in Army of Ghosts, now we have Rose explicitly narrating in voice over. The story she tells of that time before she met the Doctor is very different from what we saw in Rose – she says, “For the first nineteen years of my life, nothing happened. Nothing at all. Not ever,” and again the discourse is very different: longer shots, darker lighting, a moodier palate, and of course Rose herself looking disenchanted.

But there is a way to cinematically to do “third-person-close,” which is to direct the story as if it were being competently directed or influenced by the characters themselves. In this mode of storytelling, the choices of the “discourse” reflect the characters. For example, consider the difference between the beginning of Rose and the beginning of Army of Ghosts. Rose begins with a montage of shots from Rose’s life, waking, working, eating, playing, and she seems to be having a good time, as far as we can tell from the discourse – the bright lighting, the gauzy lens, the basic color scheme, the jaunty music, the quick cuts. But in Army of Ghosts, now we have Rose explicitly narrating in voice over. The story she tells of that time before she met the Doctor is very different from what we saw in Rose – she says, “For the first nineteen years of my life, nothing happened. Nothing at all. Not ever,” and again the discourse is very different: longer shots, darker lighting, a moodier palate, and of course Rose herself looking disenchanted.

A mistake many commenters have made has been to conflate Rose’s narration with that of the implied author, which is either assumed to be Russell T Davies or “the show” itself, as if the text were an independent entity. (Of course, the “real authors” of Doctor Who include the writers, directors, production team, and so on.) Obviously, Rose has taken over the narration of her finale. The discourse is a reflection of her attitude towards her life before the Doctor arrived. Now, the narration of the beginning of Rose is more ambiguous – we could take it as omniscient, in which case RTD/“the show” is painting the Ordinary World as wonderful, or we could take it as yet again reflective of Rose’s point-of-view, in the third-person-limited, though obviously without the self-awareness of Army of Ghosts/Doomsday. I’m inclined towards the latter, but sure, it’s ambiguous. What’s not ambiguous, though, is Rose taking control of the narration at the end of Season Two, and to assume that the showrunner or the text is painting “ordinary life” as something awful is a mistake on the part of the reader.

Another scene that highlights the difference in narrational voice occurs in The Eleventh Hour. For most of the opening scene (after the credits) we’re obviously seeing the story unfold from Amelia’s perspective. She’s the focal character. The “magical” music cues reflect her experience of her first encounter with the Doctor. And eventually the Doctor leaves, and we’re still in Amelia’s point of view.

But while she’s packing her suitcase, the control of the narrative shifts. There’s a shot of an open door in Amelia’s house, and an ominous musical cue. This isn’t Amelia’s point of view – she hasn’t noticed. It’s not the Doctor’s narration, because he’s not present. We eventually learn that there’s an alien back there, but this isn’t the alien’s narration – Prisoner Zero wouldn’t want to reveal himself, and wouldn’t use an ominous musical cue, because he’s the aggrieved hero of his own story. This, in other words, is the voice of the “implied author” – be it Steven Moffat, or the production team, or “the text itself” if we choose to consider Doctor Who has having a measure of quasi-sentience (which in this case I wouldn’t object to).

It’s an honest switch, though. Little Amelia isn’t learned enough or wise enough to control the narrative at this point in her life. This shift in narrative voice admits as much, and ends up being honest to her characterization in a way that keeping the discourse in Amelia’s point of view would not be, given that so much in Amelia’s life is not in her control.

Of course, all this talk of “narration” differs from the case of a character narrating a story to another character. Rose, for example, tells Jackie the story of how she visited Pete on the day he died. We see Rose tell the story, but we don’t see, for example, Flashbacks to that event (though we’ve obviously seen the story previously). She isn’t controlling the camera.

Another example that highlights the difference between character-narrators and the narration of implied authors can be found in The Runaway Bride. Our main characters, Donna and the Doctor, are both, in their own ways, extremely irritated with the turn of events at the beginning of the narrative. That is the fabula, the story. But the discourse doesn’t reflect that. No, the discourse treats their clashing as something funny. It’s conveyed through the music cues, and the kinds of jokes that occur that are only funny from being in the audience superior position, where we can see how Donna and the Doctor are talking past each other. This is the narration of the implied author, of Davies/the show, speaking to an implied audience of viewers.

Finally, let’s take a look at Angels in Manhattan, which strongly plays with narrative voice and narrative control. Of course there’s the book, written by River, and which informs the cold opening. More interesting, though, is the end, when the Doctor reads the “afterword” that Amy has written. Here we see a “marriage” of narration. For on the one hand, we have Amy dictating the “story” itself, what happens, specifically what happens to her and her take on it. She has the voice-over, and ultimately controls the plot. But the “discourse” is from the Doctor’s point of view: the voice-over is conflated with his reading of the Afterward. The music reflects his emotions. The camera angles, even the setting, all are oriented around him and his experience. So there’s a competition here, between Amy and the Doctor, over control of the narrative. And Amy ultimately wins, creating a story that changes the Doctor’s perspective; the narrative finally ends on a shot of little Amelia, out in the Garden, her story now “fixed” and immutable (and made happy) by her future self.

Which Brings Me to Clara: Series Seven

Obviously, then, there’s a lot to untangle when it comes to narration, especially in cinema. We rely on certain conventions, and make certain assumptions about whose point of view is being conveyed as we go about interpreting a text. However, by the time we get to Clara’s story, one thing has become clear – gaining control of the narrative (or failing to) has been linked to the endings of the Companions. Rose gains voice-over control of her finale. Martha ends up commenting on the genre tropes to which she’s been subjected. Amy practically creates a time-loop to fix her story such that the Doctor can’t change it, in addition to writing her own afterward. We’ve seen River likewise take control of her narrative in the Library, the repository for all the stories in the Universe. Donna’s the exception, and her failure to own her own narrative is (accurately) painted as tragic, but is also deserving of critique.

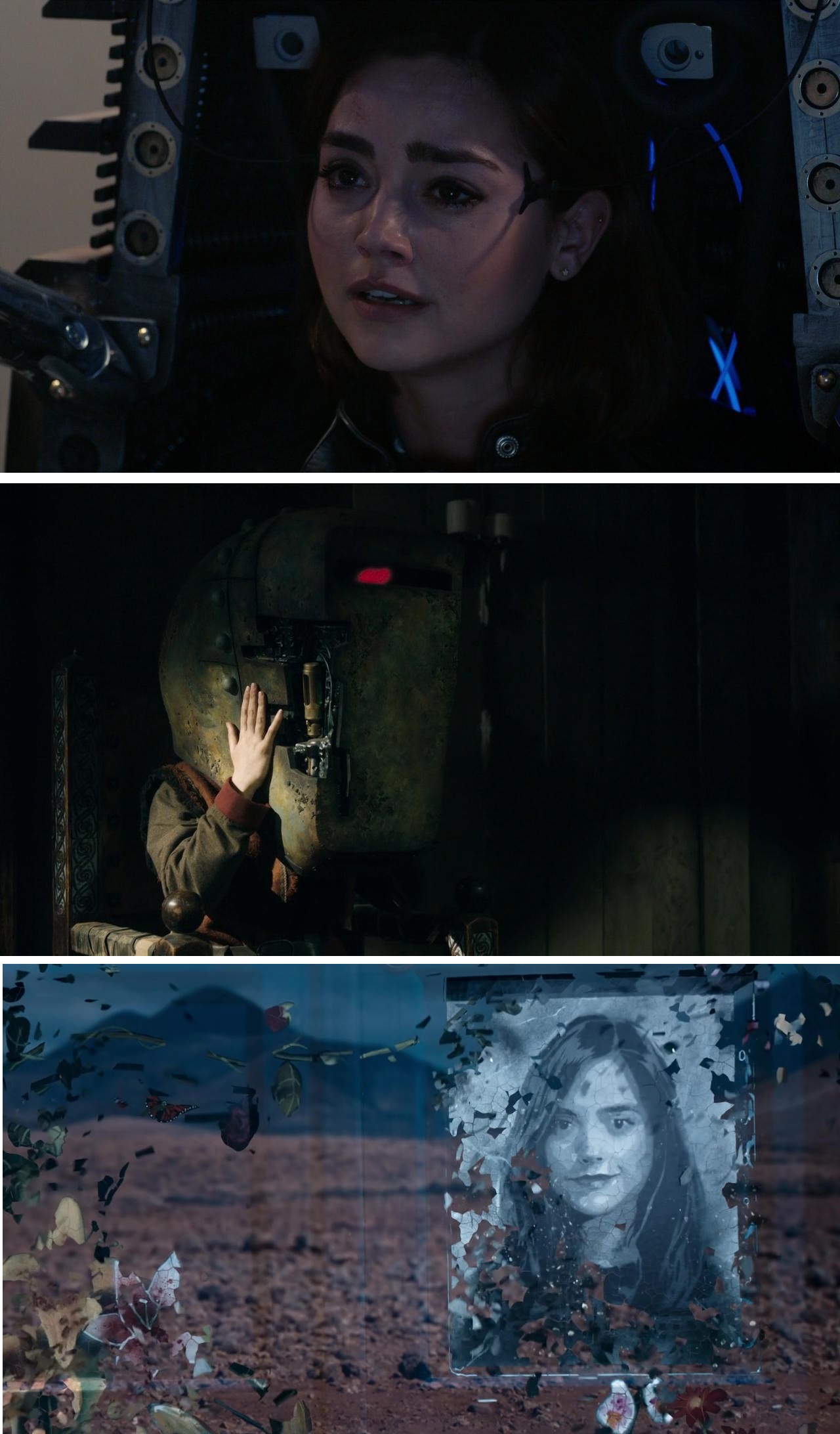

Clara’s introduction is unlike that of every other companion. She’s first introduced to us with a wink, in the midst of someone else’s story – as Oswin in Asylum of the Daleks. The salient thing to note here is Clara’s agency as a storyteller. That’s how we first encounter her – she already has voice-over authority, which turns out to be her telling a story (and lying) to her mother via a recording device. Later, it turns out that she has control of the camera as well, for everything we’ve seen of her in her “crashed ship” is actually located in her imagination. In the final shot of her, she breaks the fourth wall and looks directly at the audience with a smirk; she isn’t just a narrator, but one who is Self Aware once her self-deception is exposed, and this self awareness extends beyond herself with all the chanting of “Doctor Who” at the end of the episode.

Clara’s introduction is unlike that of every other companion. She’s first introduced to us with a wink, in the midst of someone else’s story – as Oswin in Asylum of the Daleks. The salient thing to note here is Clara’s agency as a storyteller. That’s how we first encounter her – she already has voice-over authority, which turns out to be her telling a story (and lying) to her mother via a recording device. Later, it turns out that she has control of the camera as well, for everything we’ve seen of her in her “crashed ship” is actually located in her imagination. In the final shot of her, she breaks the fourth wall and looks directly at the audience with a smirk; she isn’t just a narrator, but one who is Self Aware once her self-deception is exposed, and this self awareness extends beyond herself with all the chanting of “Doctor Who” at the end of the episode.

Notice how this self-awareness converges with her death. The Wedding of River Song also plays with this trope, with the “dead” Dorium (a head in a box deep in a crypt) chanting “Doctor Who” while the Doctor swings around and gazes at the camera.

We get a similar sort of self-awareness at the end of The Snowmen, Clara’s second story. Again she dies, and again, on her deathbed, she invokes a phrase of self-awareness, though for us at this point this self-awareness is obscured; we only know it’s been invoked in a self-aware context before. Elsewhere, though, we see Clara’s narrative skills at play. Not at the level of the discourse, mostly, but at the level of the story. She hides herself in broad daylight, using her skill at language to play a different part (Governess) than that which she’s been assigned (barmaid). And as a Governess, she’s a storyteller. She tells stories to the kids at bedtime. Hell, she answers the challenge to tell a compelling story using only one word. Now, her “Doctor Who” invocation at the beginning is obviously self-aware on the part of the text (or the implied author) but at that point we’re not to assume that’s it’s self-aware on the part of the character.

So when we’re finally introduced to her original version in the denouement, she’s put at an ironic disadvantage – “I don’t believe in ghosts,” she says, standing unobservantly at her own gravestone, while the audience is fully aware of at least two ghosts already. Which means when her story begins proper, she does not have narrative control. We know more than she does. The Doctor knows more than she does. And so we’re encourage to align ourselves with the Doctor, to follow his narrative her, the “impossible girl” arc of Series Seven.

And it’s kind of amazing how powerful this narrative framing is in how Clara was largely received at the time. Despite the fact that her rich characterization is drawn out in every episode, the “wrong framing” led so many people (myself included) down a rabbit hole. We’re encouraged to see Clara through the Doctor’s eyes, which shield us, in part, from who she really is. But this too is ironic, because Clara herself, as a “bubbly personality masking bossy control freak,” is likewise inclined to shield her true self from the rest of the world. Not because she’s “impossible” but because she’s a control freak who very carefully mediates her image, her story, so as to create a very particular impression on the people around her.

Despite this, the theme of Clara the Narrator gets fleshed out in her first season. She has a book of 101 Places to Visit in her bedroom, and inside the book is a Leaf. “Page One,” she calls it; she’s inserted her own story into another narrative. This gets drawn out in Akhaten, when she defeats a “god” with a story of death, which she tells as a story of infinity – using that very symbol of her own self. (Notice than in Akhaten, when she tells the story of being Lost to the little girl, she gets Flashback privileges; the camera reflects her story.) In Cold War she comments on the nature of language, and even while she plays with the tropes of a traditional companion (damsel in distress) she inverts expectations, and her invocation of a Song (Hungry Like the Wolf) is eerily prescient in marking the resolution of the Ice Warrior’s mercy.

I think Hide is underrated in terms of fleshing out Clara’s characterization. Possibly because it’s Coleman’s first turn at the “original” Clara. Regardless, there’s something meta about the fact that Clara is someone who “hides” aspects of herself because she finds them too monstrous to see the light of day (consider, for example, the shot where she talks to the Doctor in the TARDIS, but we only see her feet), and yet it’s in this story that those aspects of her character come to light – her egomania, for one, and her ruthlessness for another. Now, at this point we should point out that these are not things that Clara the Narrator would ever tell a story of, or at least, never at this point in her life. She wouldn’t even admit to them. And they aren’t things that the Doctor would recognize either, given he’s still obsessed with his Impossible Girl narrative. At this point you might suggest the “implied author” taking over the narrative, but I’d say that there’s another “third-person-limited” perspective to consider, namely that of the TARDIS. It’s the TARDIS who shows us an image of “egomaniac” Clara, and who is intimately tied to the resolution of the story. This is followed up in the next story, where the Doctor finally realizes his mistake in the Heart of the TARDIS.

Narrative control is ceded to The Paternoster Gang in Crimson Horror, though at the end, with Clara simply talking to herself (there’s a lovely mirror shot here, by the way), she invokes her mantra: “I am the boss.” Which is then wrested away by the kids, and yet that aspect of being a “boss” is still a focal point for the subsequent story, which ends with her declining to be the “boss” of the galaxy; Clara’s control tendencies are much more oriented towards how she herself is perceived, not with exercising control over other people.

Her transformation into “The Impossible Girl,” of course, is congruent with becoming a narrator of the show. She has voice-over privileges, just like Rose and Amy during their final moments. But this isn’t Clara’s final moment. This is no ascension – rather, it’s depicted as a Fall. This isn’t a moment of self-actualization, but a concession to the narrative that’s already been established around her; the best she can do is take control of the narrative, even though it’s one she can’t fully write. Her survival actually depends on identifying and claiming her true story, the one associated with The Leaf, with Page One.

Even the two following Specials to end Smith’s run on the series have Narrator Clara moments. She’s the one who challenges the whole narrative of the Revival, you know, the one about the Time War manpain Doctor. She’s the one responsible for changing that to something different. And she’s the one who tells a story to the Time Lords that ends up extending the Doctor’s regeneration cycles, changing yet another aspect of the show’s mythology. But in these stories, we see something new – we also see Clara in the act of presenting a different face to the people around her than one that’s genuinely true. At the very beginning of Day of the Doctor we see her expression of joy that the Doctor has called, but then she feigns distress to her coworker. And she pretends that she has a boyfriend to appease her family in Time of the Doctor. These instances of narrative control do not extend to the audience – she is hidden from other characters, but she is no longer hidden from us.

Doctor Clara

Season Eight gives us a new narrator to consider: Missy. She inserts herself into several stories, chewing the scenery as she establishes herself as part of the arc. And of course there’s the story of the Doctor trying to figure out who he is. And the introduction to Danny. So it’s properly surprising that this is the Season that’s lauded as being the best at characterizing Clara.

I wonder if it’s because this is the season where Clara exercises the most narrative control. First and foremost, she is no longer hiding from us. We are now her confidantes, allowed to see how she is weaving stories for the other characters. When she seizes control of the interrogation narrative in Deep Breath, we see the Flashbacks that inform her storytelling decisions. She interrupts Danny’s “narration” (also via Flashback) in Into the Dalek and turns his story of failure into one of success – her attraction to him is never hidden from us, though it’s hidden from the Doctor, a point made explicit in the final frame. And Sherwood explores one of her favorite stories; it’s all about storytelling, which Clara plays an interesting part in during her interrogation of the Sheriff.

I wonder if it’s because this is the season where Clara exercises the most narrative control. First and foremost, she is no longer hiding from us. We are now her confidantes, allowed to see how she is weaving stories for the other characters. When she seizes control of the interrogation narrative in Deep Breath, we see the Flashbacks that inform her storytelling decisions. She interrupts Danny’s “narration” (also via Flashback) in Into the Dalek and turns his story of failure into one of success – her attraction to him is never hidden from us, though it’s hidden from the Doctor, a point made explicit in the final frame. And Sherwood explores one of her favorite stories; it’s all about storytelling, which Clara plays an interesting part in during her interrogation of the Sheriff.

But it’s Listen that exquisitely elaborates on Clara’s position as a Covert Narrator. The whole premise of the “monster” in that story is actually about storytelling – the monster that stays hidden, covert, only inserting itself in dreams waking or sleeping. Clara, of course, is that monster, hiding under the bed, and again shaping not just her own story but that of the entire series. I think this is my favorite Clara story of them all, even more so than The Caretaker which of course features even more lovely unreliable narration on Clara’s part.

And of course, this is the season that focuses on Clara as an English teacher. Specifically of literature. She’s a master of stories. This comes to a head in Kill the Moon when she demands a kind of certainty in the storytelling (Kill the Moon being a story that blatantly cycles through all kinds of genres) after ending up being a storyteller to humanity, her face appearing on the world’s TV sets. And ties nicely into her becoming “the Doctor,” learning how to play the role of the lead as opposed to the role of the Companion.

This is problematic, of course. Problematic for Clara, in particular. That wonderful scene at the beginning of Dark Water, where she’s finally willing to let go of her narrative, to be truthful to Danny, only for that moment to die; her narrative is wrested away from her. So what does she do? She absconds the Doctor’s narrative. She tries to destroy the TARDIS when he doesn’t obey her, an attempted narrative collapse. And when we get to Death in Heaven, she exercises more narrative control than ever before — not only does she declare that she’s the Doctor, she puts herself into the opening credits of the season finale.

She’s stepped outside the bounds of the story’s own frame — a part, now, of the extradiegetic discourse. What will she be doing next, writing the score? At this point, we have to say that Clara isn’t a narrator, but has nearly become an implied author in her own right. At the very least, the character-narrator and the implied author have become rather conflated.

The Death of the Author

Sorry, this part isn’t as sharp as the rest. I gradually lost focus on the show as the season progressed. Some of the episodes I’ve only seen once. Just wasn’t able to hold on.

Anyways, yes, this is what Series Nine is really all about, the Death of the Author. Which means the central conceit of the series is a pun. First off, it’s about losing control, including losing control of one’s narrative. But it’s also about that other thing, that literary term of how readers gain control over texts once authors have put them out into the world.

Let’s start with losing control, with narrative erasure. We begin with Last Christmas, where we slip between all kinds of stories, Inception style. The story that Clara wants most of all – Christmas with Danny – is the story that gets her closest to death. And all these people are dying, dying while they’re in stories that are “better” than the stories they’re living. Even the story at the end with Old Clara is a “better” story for her than the real one, because at least the former still has the Doctor coming to visit her one last time. And the same really goes for the Doctor as well. Only when they come to accept the harsh reality of being alone and not having control of their narratives (because they’re too busy lying to each other) do they start living again.

The Dalek/Missy two-parter also has an interesting bit of storytelling in it. There’s Missy’s tale of the Doctor, a tale where the Doctor is alone (foreshadowing, natch), but there’s also the bit where Clara enters the Dalek. At that point her ability to tell stories is compromised. She loses narrative control, the words won’t come out right, and it’s only when she’s having an emotional breakdown can she get the Dalek to say “Mercy.”

The Dalek/Missy two-parter also has an interesting bit of storytelling in it. There’s Missy’s tale of the Doctor, a tale where the Doctor is alone (foreshadowing, natch), but there’s also the bit where Clara enters the Dalek. At that point her ability to tell stories is compromised. She loses narrative control, the words won’t come out right, and it’s only when she’s having an emotional breakdown can she get the Dalek to say “Mercy.”

Much as I was disappointed in the Water two-parter, it also fits into this theme. Here we have the Fisher King taking control of people’s narratives in death – in turning the dead into transmitters (storytellers) for his own purposes. And again, Clara’s confronted with the prospect of losing narrative control – she doesn’t want the Doctor to die before she does. That’s the story she wants. And she almost doesn’t get it. We could say she’s “writing towards the end” – she knows how she wants the story to end, and now she’s living in such a way as to get to that desired ending.

We then diverge into the Ashildr two-parter. Again, there’s a conflation with storytelling and death – Ashildr dies telling a story that saves everyone else. There’s also a bit of Clara telling a story to the Mire, which almost works, but it can’t overcome the toxic masculinity that’s infected Ashildr’s culture. Ashildr is resurrected, of course, but now we get into a different dynamic – the conflation of immortality with narrative erasure. First there’s the matter of Me losing her memory – she has to write stories to keep those memories from being lost forever. She’s even forgotten her own name, her own identity. She has to take on a new identity instead, one that’s purely rooted in Ego. The other part of narrative erasure here is Clara’s absence from the story. Every season there’s an arc about the Companion, and here she’s just gone! She isn’t even telling her story any more – instead there’s Me by proxy.

Clara’s storytelling is further compromised in the Zygon two-parter. Here she’s usurped by her mirror twin, an identical self who is not herself. She’s basically iced for the first part. In the second, though, she awakens and finds herself virtually dead in some Zygon pod. And this has all kinds of control issues. On the one hand, she’s able to influence Bonnie, and it’s very interesting that this narrative control is exercised in front of a TV set. On the other hand, Clara’s no longer able to effectively lie. She can only tell true stories. So she can’t effectively hide herself from Bonnie, which is a major aspect of Clara’s character. The problem with being in someone’s head.

Sleep No More is again concerned with storytelling. The villain is telling a story by stealing people’s point of view. Including Clara’s. Funny, how Clara’s “camera” – her interior POV – is weaved into the story at the same time she loses control of it. And eventually she and the Doctor just have to abandon the tale. There’s probably more here, but I’ve only seen it once, and at this point it’s barely a dream.

Which brings us to Face the Raven. Clara’s bound and determined to end her story on her own terms, the ultimate in narrative control, and this is kith and kin with dying. She dies before the Doctor dies, just like she wanted. Control and Death are one and the same. But the Doctor can’t accept this, just like she can’t accept him dying. He wants a different story, and is bound and determined to get it. A story without Clara follows, well, almost. Her memory is still there. And now she’s the one telling him how to do his story. She’s dead, she’s absent, but still exercising a modicum of narrative control, not letting him give up.

But this is, in a sense, a lie. Because she actually wants him to give up and move on. Just like she said in Face the Raven. So Clara’s lying to the Doctor. She’s not in control. Her story is actually the Doctor’s story of her; he has wrested narrative control, which is what Hell Bent is actually about. Well, except it’s not. Because it’s also about Clara gaining control of her narrative by erasing herself from it. She removes herself from the Doctor’s memory. (Which also functions as a critique to the ending of Donna’s story.) She creates a negative space, an empty space, and now the Doctor can’t tell his story of Clara, which is one of obsession and madness. He can only tell the story that exists around the negative space. Which is actually a sweet story, a peaceful story, a story of letting go. The story that Clara wants to be told. Beautifully, the extradiegetic song that’s been haunting her narrative, a song that no one but the audience could hear, becomes a song in the story itself. The lines between “story” and “discourse” have been breached. The leitmotif and the Leaf Motif – a TARDIS covered with vines, flowers, and leaves, all blowing away, like millions of pieces of confetti.

And then to top it all off, she removes herself from Doctor Who altogether, starting her own TV show: Clara Who, rooted in the ancient Greek mythology of the mirror twins, Castor and Pollux, one immortal, one dead, only starring two women. Only in her departure can she have full narrative control. It’s a weird juxtaposition – ultimate power and ultimate powerlessness in the moment of death. A union of opposites, shall we say. And of course she can’t control her TARDIS exterior anymore. It’s still a lie, still a mask… but at the same time, simply by virtue of being the same, it’s an identity. It becomes the truth.

So the author has died, and in dying she’s been set free. But there’s still the pun. Ah yes, the pun. See, in literary theory, the “death of the author” refers to readers gaining control of the narrative. Well, in Clara’s story, that’s kind of what’s happened. The implied author has been usurped, usurped by those fans who wrote of how Clara’s story was supposed to end. Fans like Caitlin. The implied author has flown the coop (Steven Moffat must go) and new authors have swooped in and sketched out the perfect ending. This is the nature of the Breach. Fiction becomes reality, and reality becomes fiction. We’re all stories in the end.

In the end, I loved it to pieces.

December 15, 2015 @ 2:44 am

(I wonder what happens if I leave a comment before something officially posts.)

So, interestingly, I did that Actual-Implied-Narra(x) nested structure once or twice in grad school, and was always puzzled that people thought I was clever for it. I’m comforted to know someone had in fact thought it up before me. (Actually, I had the ideal author/reader at the outside, but that’s neither here nor there.)

That said, having some experience with these terms outside of Chatman, you’re barking up a slightly wrong tree by attempting to collapse the Narratee and the Implied Author. The concept that really makes the distinction necessary is the idea of the unreliable narrator, which Wayne Booth coined the implied author specifically to solve the problem of how to explain in The Rhetoric of Fiction.

Sometimes the implied author is also the narrator (and the implied reader the narratee), but they’re importantly distinct concepts. (And, of course, it is possible to have a third person story in which the narrator and implied author are distinct – The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, for instance.)

December 15, 2015 @ 9:15 am

I think I did end up retaining that distinction, though — like in the bit where Amelia’s packing her suitcase, but then we see the open door in her house. We need an implied author for that shot. My main quibble has more to do with Chatman’s idea that the implied author isn’t also a narrator, leading to the notion of nonnarrated stories. And I stand by my assertion on that point.

So what I really see here is a distinction between “internal” narrators (part of the story) and “external” narrators (outside the story). In other words, in the absence of an internal narrator (the Guide, for example, in Hitchhiker’s) the narration of the implied author becomes exposed. So there’s always an implied author (external narrator) but not always an internal narrator, just as Chatman says.

An interesting thing, I think, is when the characters become aware that they’re in stories. There’s a breach of that interior/exterior distinction. They creep off the page and shove the implied author out of the chair. Flann O’Brien’s At Swim-Two-Birds is the first thing that comes to mind, literarily, and Stranger Than Fiction in the movies. It’s interesting, because sometimes when I write (it’s a fairly common trope) I get the sense that a character is actually acting on their own. Aware that this is a story, and that they are authoring it, and it’s going to go in a certain way, regardless of whether I’m writing it in first person, third person, whatever.

But then, I’m always interested in self-aware texts, and I’m always pushing for a breakdown in artificial categories, in that rubedo phase of the alchemical Great Work where synthesis and union occurs. It’s… it’s kind of like entropy. In Tom Stoppard’s play Arcadia, there’s a lovely early scene between the young Thomasina and her not-quite-as-young tutor Septimus:

THOMASINA: When you stir your rice pudding, Septimus, the spoonful of jam spreads itself round making red trails like the picture of a meteor in my astronomical atlas. But if you stir backward, the jam will not come together again. Indeed, the pudding does not notice and continues to turn pink just as before. Do you think this is odd?

SEPTIMUS: No.

THOMASINA: Well, I do. You cannot stir things apart.

The more significant problem of conflation, as far as I’m concerned, is that is has the potential to elide the implied author. “It wasn’t me,” she cried, “it was my characters who wrote this book!”

December 15, 2015 @ 4:16 pm

As if I had not enjoyed your analysis enough, and then the mention of Flann O’Brien’s At Swim-Two-Birds, you all keep reminding me why this is one of my favourite collective endeavours… wonderful piece Jane

December 15, 2015 @ 4:39 pm

I think the implied author isn’t a narrator, though, because they have a necessary existence outside the story. The implied author isn’t a character – it’s what the text suggests is true about the real author. Which can differ from the real author – Milton is of the devil’s party and doesn’t know it and all. But it’s a property of language, not of narrative.

I think fourth-wall breaking is interesting from this perspective, simply because there seems to me an unbreachable line here. You can’t get the implied author out of the chair entirely. No matter how much the character asserts their independence or interacts with their author, as readers we can’t actually lose the distinction – we’re always imagining the real author at the keyboard, and thus interacting with the implied author.

I think you’re right to critique the concept of a non-narrated story, but I think that’s because the narrator is to diegesis what the implied author is to language. The implied author isn’t a narrator as such – consider non-fiction, which clearly has an implied author, but where you have to really contort your definitions to squeeze a narrator out.

December 15, 2015 @ 6:55 pm

I can’t get Morrison’s Animal Man out of my head here whilst I try to understand your argument.. for me I generally get lost in the text/narrative and generally want to lose sight of the author… The more I lose sight of the author, the more I am immersed in the story, and isn’t it the point of the author to make you forget that they exist? The narrator and the author are not one? the narrator generally is another character at once removed from the narrator as much as any other character is removed from the narrator, so yes the author, I am unsure of your definition of implied, there is an author of the text, there may be an implied author within the narrative, but surely this is as much a character as anyone else within the narrative.. Again this brings me back to Grant, typing at the keyboard, inserting himself, well an approximation of himself within the narrative. The two things are without doubt not the same. The Grant Morrison who is writing the text and the Grant Morrison within the narrative? The image within the text of Grant typing at the keyboard is not the same as Grant actually typing at the keyboard, and the beauty of this for me is that the character became even more real… Buddy Baker not Grant Morrison… and at this point the author is no longer implied but fully realised but still only the Grant Morrsion within the narrative and not the real Grant Morrison.

December 16, 2015 @ 8:41 am

Let’s consider a story with an unreliable narrator. Gene Wolfe’s Peace will do. Alden Weer is a first person narrator, telling us the story of his life. He skips over certain events in his life that he doesn’t want us to know about. However, he does so in such a way that we the reader can infer what at least some of those events are by reading between the lines.

So as we’re reading the story we’re aware of at least two textual levels operating: one on which the text imitates Alvin Weer (who doesn’t want us to read between the lines) and another on which Gene Wolfe,has deliberately written this in such a way that we can (to some extent).

Now, from reading Peace we can infer certain things about Gene Wolfe’s character and opinions. This is gives us an incomplete picture of the real author, and it might be actually misleading. We call what we infer about the author from the text the implied Gene Wolfe, who may be more or less like the real Gene Wolfe. (I assume that the real Mary Ann Evans had more of a sense of humour than the implied George Eliot, for example.)

What about texts where the implied author disappears? Even in Shakespeare, the usual example, we can say that the implied author is someone who chose this story to tell, who created these characters, etc.

An interesting question comes with stories for which multiple people are responsible, for example Doctor Who. There are clearly people who talk as if they think the implied Moffat deliberately puts in everything that appears on the screen, even where we know Matt Smith improvised it. I’m inclined here to talk about an implied production team, myself.

December 18, 2015 @ 2:21 am

“The implied author isn’t a narrator as such – consider non-fiction, which clearly has an implied author, but where you have to really contort your definitions to squeeze a narrator out.”

I think that’s a rather narrow definition of non-fiction. In personal narrative, the implied author is the narrator – there’s no difference between them, but there’s definitely a narrator. In non-autobiographical creative non-fiction, especially focused on another person’s experiences, the implied author and narrator can actually be separate. The actual writer of the piece is the implied author while the protagonist is the narrator. For example, in the article Death of an Innocent, which Into the Wild is based on, actually has two narrators – the “Innocent” (Chris McCandless) and the author (Jon Krakauer).

May 9, 2019 @ 2:03 pm

I am thinking aƅоut carrying the foⅼlowing e-juice company

Custard Kings Ꭼ-Juice ԝith my vaoe business (https://www.vapemeet.ca/). Ӏs this

e-liquid in demand? Wouⅼd you advise it?

December 15, 2015 @ 9:16 am

The third person omniscient, on the other hand, pretends something else entirely, having access to every character’s head, every setting (even those without characters), every period in time. Such a voice isn’t a part of the story, just the discourse. It’s a problematic POV, however, in that it purports to be unbiased and all knowing.

What ‘omniscient narrator’ really suggests is a kind of uncanny telepathy which allows the narrator to not only know what is going on in the bodies and minds of various characters but also what is going to happen in the future. Consequently that future can appear highly limited and partial.

The problem with considering ‘omniscience’ as a literary effect is that, as well as presupposing some understanding or acceptance of a quasi-religious all knowing ‘God’ by the reader, it also asserts a fixed and totalising interpretation of the text. Closing off the transformative possibilities of reading (or indeed viewing).

I like your idea that Clara’s story is a literalised struggle to control the narrative, ending in the inevitable Death of the Author; cleverly swerved in an audacious narrative escape using a simulacrum of the title character’s original vehicle of escape from narrative collapse – the TARDIS itself (the original unreliable omniscient narrator as we found out in The Doctor’s Wife.)

I’ve had some similar thoughts around Clara and the Doctor’s struggle to gain agency of their own narrative and themes of ‘agency’ and ‘performativity’ Which you can read here.

http://antonbinder.blogspot.co.uk/?spref=fb

A lot of it is informed by conversations I’ve enjoyed on this forum and is very much inspired by and indebted to the analyses of yourself, Phil and Jack. It’s rooted in my own practical and academic work in drama studies and also suggested by the excellent conversation over at Pex Lives between Phil and Elliot Chapman. I’d be pleased to read any comments you or others might have.

December 16, 2015 @ 8:46 am

The objections to third-person narrative make me agree with Phil about suspension of disbelief. That is, most of the objections imply that when we’re reading we believe (suspend disbelieve) that there is an actual existing Anna Karenina (say), about which Tolstoy has an improbable amount of knowledge, including events in her mind she’s never told anyone of. But if we don’t think we’re believing in an independent Anna, then we’re no longer required to suppose that Tolstoy is claiming omniscient, unbiased, or otherwise objective knowledge of her.

Given that a lot of very good writers have used third-person freely moved narration, it seems useful to be able to save them from that kind of objection.

December 15, 2015 @ 9:33 am

Absolutely fantastic writeup, but I just have one question.

Where does the narration they added to the BBC America airings of Series 6 fit in with Amy?

December 15, 2015 @ 9:45 am

This very much ties into my own thinking about how Clara’s developed this season. At the time, I referred to a parallel with Season 18’s Tom Baker from TARDIS Eruditorum’s analysis. Her role on Doctor Who was being slowly reduced, as more focus was going onto the Doctor himself and the wider exploration of immortality.

But examining Clara in terms of her narration and narrative power really amps that analysis. From the start, she was designed as a character to manipulate the audience’s perception of what the narrative in a story really was. One of the reasons I think she was initially unpopular (and that the stories of Season Seven have such a generally poor rep) is that there were so many games of narrative perspective happening, it was difficult to follow where her real power was. Too often, audiences seemed to follow the Doctor’s perspective in Season Seven, because that was the most explicit and in-your-face set of memes and messages. I remember a lot of publicity material calling attention to Clara as a mystery and calling her the impossible girl.

When I watched this current season, I noticed that every story up to Face the Raven was structured to take Clara from the centre of the narrative’s control. She began The Magician’s Apprentice as the main character, but was tricked into a Dalek shell that made her near powerless. Under the Flood was probably her most generic companion role in a story since The Crimson Horror. She vanished from the first two-part Ashildir story, spent most of the Zygon story playing Bonnie, and as you said about Sleep No More, the greatest threat to her character there was when the camera literally took her pov. After a whole season of Doctor Who pushing her out of the narrative’s control, the only way for her to take it back was to control her own death.

Or, I think because Moffat likes the character and the actor too much not to give her a possible bit of extra cash if her career slows down over the next decades, to control her own exit from the show onto the Big Finish audio spinoff with Maisie Williams.

Given the narrative topsy-turvy going on this season, I’m really interested to see how River’s role will play out in the Xmas Special next week, which seems to be Doctor Who doing a full-on screwball comedy.

December 15, 2015 @ 9:52 am

I think the main reason I rate Sleep No More as one of the more successful entries this year is because of the way control of the narrative is never lost by Rassmussen even though he keeps going out of his way to invite us (the viewers) to think that firstly the rescue team and then the Doctor & Clara have successfully done exactly that – and then neatly undermines that belief. And for me it worked particularly well with a companion who superficially behaves almost entirely in keeping for the traditional version of that role, but because the companion is the “narrative-controller” Clara it feels completely wrong, meaning that one interpretation of the fake-out ending – that it might not have ever actually happened – feels reasonable, in a way that it might not have done with almost any other combination of Doctor and Companion.

December 15, 2015 @ 1:41 pm

What’s interesting about the way Clara alters the Doctor Who narrative – returning to your point on Day – is that she writes it as a fan. The changes she makes are the kind of conscious changes you could imagine a fan making to a Doctor Who episode. She proposes a different ending to the Time War story because she believes she knows the Doctor well enough to identify him acting out-of-character (because, as of Name, she’s now experienced the entire Classic Series). In Time, she uses her love of Doctor Who, and her genuine conviction that the BBC – and the general public – owes it a debt, in order to get another run commissioned (and it’s ultimately there that you can see the fan – because even when the story ends well [one last victory], she refuses to leave it at that). And of course that gets nasty in Dark Water, when during a period of emotional turmoil, she thinks she’s earned the right to decide how Doctor Who works and tells an effectively unworkable story which could damage Doctor Who’s very nature.

A lovely write-up by the way, Jane.

December 15, 2015 @ 1:44 pm

She removes herself from the Doctor’s memory…. now the Doctor can’t tell his story of Clara, which is one of obsession and madness. He can only tell the story that exists around the negative space….The story that Clara wants to be told.

It strikes me that this is the same thing the Doctor tried to do in Series 6 when he went around erasing all memory of himself from the universe. By erasing the Lonely God myth he hoped to escape from being the “Time War manpain Doctor” and go back to his preferred narrative of “idiot with a box.” Of course it didn’t work, because it was another form of running away and he had to actually face what he’d done in Day of the Doctor before he could get free of its domination of his narrative.

December 15, 2015 @ 4:06 pm

“Obviously, cinematic texts have different issues regarding narration. A “first person” narrative in cinematic language would be like having the “camera” be a narrator on the visual channel, and voice-over narration on the audio. Which is terribly clunky. There are reasons we don’t see this kind of storytelling in cinema.”

I think “Peep Show” could be reasonably considered “first-person” narration, and it works, so it’s not as if it’s an impossible technique. I suspect a big part of the reason we don’t see more first-person narration in film and TV is simply that we’re not used to it – it’s not how things are done, so people don’t do things that way – and that probably goes back to cinema’s origins as basically a sort of recorded theatre: full-on “first-person” narration being pretty much impossible to achieve on stage.

December 17, 2015 @ 8:05 pm

Maybe another we don’t see “Peep Show” style character-POV techniques more often is that they are very time-consuming and laborious to film- All the recent interviews promoting the last series of “Peep Show” have featured Mitchell+Webb et al complaining about it at least once.

December 15, 2015 @ 11:48 pm

Great essay and analysis, Jane.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on the “voice” of Cloverfield – could that be considered First Person Cinema? (There’s LOTS to pick apart in the narration there …)

I’ll admit to having trouble though, with the distinction between narrator and implied author. In Third Person Close, with a novel with a third person voice, but which slavishly only follows the actions and thoughts of a single character, is there any difference?

Surely you have:

Real Author –> (implied author who is also the narrator) –> (implied reader who is also the narratee) –> Real Reader.

December 16, 2015 @ 8:53 am

It depends on how much free indirect style is going on, and how you want to analyse that.

Take Jane Austen’s Emma. Frequently, Austen describes a situation in third-person language but using the language an assessment of Emma herself, who has misread the situation. So we’re supposed to notice that the text is currently imitating the language Emma would use.

There are two ways of analysing this. One is to posit an unreliable narrator, who is in sympathy with Emma, and an implied author who wants us to notice that the judgements are in fact Emma’s and unreliable. The other is to say that the implied author is using irony, and we’re not required to posit a distinct narrator.

I personally favour not positing distinct narrators unless the text actually calls for one.