Epics and Monsters

Parts of the below were developed in conversation with Niki Haringsma, whose Black Archive on ‘Love & Monsters’ is forthcoming, and who was recently heard in conversation with El. Again, I alone am to blame for the faults of what follows.

Parts of the below were developed in conversation with Niki Haringsma, whose Black Archive on ‘Love & Monsters’ is forthcoming, and who was recently heard in conversation with El. Again, I alone am to blame for the faults of what follows.

*

So, contrary to those who feel it’s become ‘too PC’ (a misprision that is interesting by itself), Doctor Who these days looks increasingly like it is taking a reactionary turn – albeit one of a complex kind – as it seems to drift from being an “accidental critique of milquetoast liberalism” (as Kit Power put it) into an outright accomodation with the systems it has found itself unable to effectively struggle against. This makes Chibnall’s show, in its own way, a mirror to Moffat’s, which was also deeply concerned with the limits of resistance to systems.

This is a space for analysing the political attitude found in the content. But there is also reason to look at what the form tells us, what it assumes, what it permits, etc. As we’ve already talked about elsewhere, the form and content are actually inextricable.

Let’s take a detour into Brechtian ‘Epic Theatre’.

Brecht’s theatre doesn’t aim to ‘resolve’ political questions even when it is morally and politically clear because – at least in his mind, and one is free to disagree with him – its moral and political project is an invitation to the audience to contemplate profound contradictions and problems in society.

The problem with bourgeois theatre, for Brecht (and he sees Lukacs as doing the same thing) is that it is “afraid of production”, i.e. it hides it. Realist theatre (Ibsen, Strindberg, etc) tries to create an illusion of realism, an empathic connection with the characters, which not only smooths over social contradictions but also masks production itself. (Modern TV, which strives to look cinematic, arguably does this same thing far more than old-school TV, which was often more-or-less televised theatre.) Brecht dislikes this as a Marxist, and one with a particular emphasis on production as fundamental to social existence (an emphasis which I personally think is quite proper for a Marxist, but which is sadly lacking from much actual Marxism).

It is this masking of production which, perhaps more than anything else for Brecht, creates the bourgeois illusion of fixity which he aims to dispel. Epic Theatre concentrates on production both in terms of how people actually produce history and in terms of how theatre itself is produced. This coherence is, paradoxically, a key way in which it aims to reveal social contradictions.

The irony is that modern Doctor Who is arguably a lot less like Epic Theatre in this sense than most classic Who manages to be by accident! Classic Who is arguably far more concerned with political issues (re society and history) than New Who. But it also accidentally estranges the audience by highlighting its own processes of production, simply by virtue of its production values being so shoddy that it inadvertently showcases them! (This must be particularly true for audiences no longer watching it in its original context – like people on Twitch.)

(It’s also complex, because the ‘realism’ or ‘believability’ classic TV SF reaches for and fails to grasp is not always the same thing as verisimilitude… but that’s a total tangent that we’ve touched on elsewhere.)

Raymond Williams pointed out the strange contradiction between the radical content of much social realist drama and the conservatism of its theatrical realist form. Doctor Who always had an odd, accidental escape hatch here. Take, ‘The Sun Makers’. The message is (I’d say) politically radical, yet it strives for conventional visual realism… and yet it can never achieve visual realism because the realism it strives for is the realistic visualisation of a fantasy scenario that a) the BBC designer is not accustomed to envisaging and b) can never hope to achieve anyway! It thus accidentally sidesteps the problem. Modern bigger-budget, CGI-laden Doctor Who can achieve this ‘realism’ (i.e. an agreed-upon and notional ‘feel’ that corresponds to an ideological notion we call ‘believability’) in its depiction of ‘the future’ or alien planets, etc. This is one reason why ‘Oxygen’ seems less radical than ‘The Happiness Patrol’.

Modern Doctor Who seems a lot less vulnerable to revealing its ‘producedness’. At the same time, the greater technological advancement and bigger budgets, and also an expanded sense in directors of what television can and should do in terms of technique, leads the modern show to be a lot more visually flexible and aesthetically self-aware, and thus much more revelatory of its own form. The irony is that this becomes possible because of a wider technological revolution in visual arts which makes such things so commonplace that they are expected, taken for granted, barely seen by many. They fail to estrange because such aesthetics are now part of how the illusion of realism – as currently understand by audiences – is achieved. This is ironic, given that both Brecht and Benjamin expected and wanted estrangement to continue in – perhaps be extended by – new forms like radio and cinema, and television by extension. Benjamin saw montage (the basis of so much modern cinema and TV aesthetics, based as it is on editing) as the technological-media equivalent of the alienation effect. Trouble is, we’ve come to expect the superimposition and interruption of montage, and thus to fail to be estranged by it!

Of course, Brecht went further than just expecting self-awareness of form to estrange audiences. He actively alienated them in ways that simply are unthinkable in terms of modern TV practice, not least his approach to acting. Acting in Epic Theatre is not about creating emotional mimesis and thus empathic connections. It’s about gesture, demonstration, etc. Even the most grotesque performance in Doctor Who – Peter Kay in ‘Love & Monsters’ for example – doesn’t do anything like this. Elsewhere, the episode actively aims to portray emotional states and engender empathy. The new series is, of course, very aware of the need to be ‘emotional’. The bizarre nature of some of the events which form the basis of some of the emotions is contextualised – and thus arguably neutralised – by the genre context, and by the very technical sophistication the show now has, which is the bare minimum modern SF/Fantasy audiences now expect. The expectation neutralises any potential estrangement. A modern audience is likely to be far more estranged by ‘The Web Planet’ than anything in ‘Love & Monsters’.

Brecht himself, later in life, complained that many of the formal aspects of Epic Theatre had been adopted sans their content. Owen Hatherley says, in Militant Modernism, that 21st century culture is steeped in “a kind of cynical Brechtian[ism], where the alienation effect’s insistence on the stepping in and out of roles is a way of avoiding ever actually saying anything”.

It seems to me that the people most likely to be estranged by the technique and style of new Who are likely to be old school Doctor Who fans! And that the degree of their estrangement is likely to be limited to the show itself! The whole of the new series did this, almost from the start. Even to old school fans familiar with the forms of present day mass culture, seeing them applied to Doctor Who was shocking. I remember the ‘Scooby Doo’ chase sequence at the start of ‘Love & Monsters’ causing a great deal of distress in some quarters at the time. It’s likely that the cries of “it’s silly!” were fumbling attempts to express a concern that was more about alienation from the ‘normality’ of Doctor Who (as it was understood by some) by the sudden introduction of such metafictional techniques. In the classic series, even such comparatively routine devices as voiceovers and flashbacks were rare.

This seems to chime very nicely with the episode’s concentration on fan politics. Part of the point of estrangement is to defamiliarize aspects of social reality taken for granted… like fan culture? Could fan culture actually be the only aspect of social reality that anyone (a minority) in the audience is likely to feel newly-estranged from when watching ‘Love & Monsters’? Yet, is fan culture actually like that now? Of course, one could look at the fan dynamics in LInDA as a metaphorical expression (one that is ironically very material, very physical) of online fan dynamics. Kennedy is the irruption into online spaces, and thus new/burgeoning forms of fan social interaction, of an older form of fandom, one dominated by a few people of a certain type…

(We see that the concentration on fan reception and politics is far more about consumption than the more-Brechtian concentration on production. The episode could be looked at as a commodity critiquing some ways in which it is consumed, favouring others – which is a very common attitude in consumer culture now, with its association of products and brands with particular values, etc.)

On the other hand, going back to production, and speaking of online spaces, the other thing that strikes me about Elton’s video, re form and methods of production, is that it (now) looks like someone’s YouTube video. This leads me to think of the underlying imperative of Brecht’s Epic Theatre to revolutionise the technical means of production of theatre. Whatever else there is to be said about YouTube, it does represent a further (and somewhat radical) extension of the tendency identified by Benjamin for people in modern life to be surrounded by newly available technological ways of engaging with or in cultural production. It can’t be seen as ‘Love & Monsters’ own fault that it came along before we realised the sinister role that YouTube (etc) would come to play in 21st century politics.

Doctor Who doesn’t revolutionise televisual methods of production anymore. It is no longer ‘needed’ for that function. The television and film industry is so reliant on the Fantasy genre, as filtered through a certain ideological conception of ‘realism’, that it spurs such revolutions of technique itself. Yet have we reached – or at least neared – the threshold of such ‘realism’, at least at the apex of the industry’s spending capacities, and within the confines of the formats we currently have? There is a way in which this is like Big Pharma, spending huge amounts on R&D chasing increasingly unlikely ‘breakthroughs’ while also chasing the ‘perfection’ of what we already have, thus pushing itself into increasing complexity that actually undermines them… and all while spending gargantuan amounts on advertising and marketing in order to cover up the basic lack of any further major progress.

Doctor Who is now just a small and relatively cheap corner of this industry. But its very nature as Doctor Who seems to mean that it – as a hermetic mini-meta-genre all to itself, albeit a formally stagey one – gets pseudo-revolutionised internally, at least in the perceptions of some of its fans, simply by being made now rather than just having been made in the past.

Meanwhile, there are gestures towards recognition of a kind of recurve away from this ‘progress’ in Doctor Who. ‘Love & Monsters’ contains one, being framed as Elton’s home video. Today, it looks like a YouTube video. Like the one that opens Series 11. This could even be seen as a reference to a new kind of cultural production – with all the paradoxical promises of democratisation and problems of capitalist enclosure, fascist infiltration, etc, common to all online spaces – that estranges social life via an entirely new approach to narrating experience, including fan experiences.

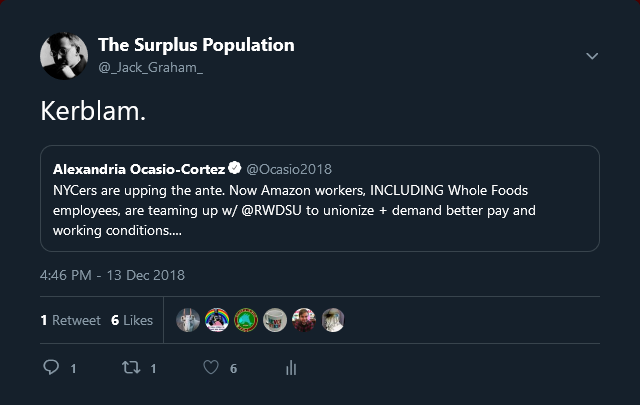

But fan experiences are, ultimately, only one part of how a television episode is socially understood. There is a sense in which ‘Kerblam!’ will have been far more of a shock to fans – and only certain kinds of fans at that – than to the general public at large. It is suggestive that the public conversation around this series has been about its supposedly drift towards being “too PC”. Part of this is undoubtedly the political-illiteracy of the media tasked with creating content about the new show. But there is also a sense in which, despite all the accomodations Series 11 has so far made to those systems it doesn’t like but finds insurmountable, it is still perceived as being ‘activist’ in its approach. This is probably because of the aesthetics it has chosen. The aesthetics of diversity and representation, and also of engagement with history, of ‘period drama’, etc. Aside from their political content – i.e. what is actually said and done in the story – there is a sense in which stories like ‘Rosa’ have a political form which determines how they will be understood. ‘Rosa’s engagement with the history it represents is compromised, a form of neoliberal Whiggism with passivity built into it, along with unwarranted triumphalism about the present. But ultimately, the way it has been understood has been far more down to its aesthetics as costume drama, and as an unprecedented engagement with issues the show is not seen as usually touching. It is seen as a serious intervention, and evidence of a new way of doing things.

Yet it has, at base, that same masking of production that Brecht criticised. This is common to all new Who, and to so much media now. And it carries within it today the same problems it always did.

December 14, 2018 @ 4:57 pm

“The irony is that modern Doctor Who is arguably a lot less like Epic Theatre in this sense than most classic Who manages to be by accident!”

This is an excellent observation.

Conversely, I think that staging Brecht in the modern world requires real imagination and stepping out of one’s hard-learned sense of “professionalism” or “verisimilitude”. Brecht is very, very easy to do badly, flatly, unengagingly, and preachily. In the UK, only the National Theatre’s version of the Threepenny Opera a couple of years ago has impressed me.

Might I suggest “defamiliarization effect” (a word you nearly use at one point) rather than “alienation” as a better translation of Verfremdungseffekt? It’s what is taught now to students of Brecht in German departments, I believe (now being about 4 years ago, when I last studied him), to re-emphasise the idea of showing you anew and in a strange light the apparatus with which you have grown comfortable as opposed to laying too much emphasis on “wanting to upset/annoy/piss off the audience”, the unfortunate, quasi-trolling connotations of “alienate”. Though in the case of Brecht such reactions may well be valid too, and the term works well for old school fans tearing their hairs out over Love & Monsters.

Incidentally, I think the only way a modern DW episode could achieve the same degree of “showcasing its producedness” would be a live broadcast. Which I would be totally up for, especially if you have a clever subversive writer doing it who can weaponise the concept of “event TV” (this is what’s going on while you’re gathered around the telly, perhaps? idk).

December 15, 2018 @ 8:38 pm

While not super-expert on Brecht, I like Jack’s use of “estrangement”. It seems to catch the idea, somehow, in a much less clunky way than words like “alienation” or “defamiliarisation”.

December 16, 2018 @ 11:16 pm

Fascinating indeed. I think “alienation” here may after all be the best term, simply for the echo it carries of “alien”, not an unrelated concept. Two further observations:

1) Special effects date, as do the conventions used to give the impression of “realism” at any given moment. Sure, the production values of classic Doctor Who were shoddy even for the period, but part of the “alienation” we feel watching them now is, simply, historical distance. Anyone going back to the current episodes forty years on may not feel so differently.

2) A degree of estrangement is built into Doctor Who through the nature of the main character, who is not human, not bound by human limitations, and prone to “impossible” flippancy in the face of life or death situations. The extremely non-psychological acting of Tom Baker would make perfect sense in a Brecht play. Some of this carries over into the current run: to whatever degree the Doctor remains “alien”—which varies with each incarnation of the character—(s)he can perform some of the functions of a Brechtian narrator. I would also point to John Simm’s Master as a figure defined far more by “gesture, demonstration, etc” than by any kind of psychology—the apex of “alienation” in the modern show being his season 3 dance to the Scissor Sisters.

December 16, 2018 @ 11:46 pm

Personally I agree that ‘defamiliarisation’ is preferable, and it was the one I used in my brief flirtation with Russian formalists. ‘Estrangement’ sounds, to me, too much like it relates to the imposition of emotional detachment, or the ‘Othering’ of someone or something. And ‘alienation’ has all sorts of baggage from other uses.

December 14, 2018 @ 7:09 pm

Fascinating stuff.

“Classic Who is arguably far more concerned with political issues (re society and history) than New Who. But it also accidentally estranges the audience by highlighting its own processes of production, simply by virtue of its production values being so shoddy that it inadvertently showcases them!”

“The irony is that this becomes possible because of a wider technological revolution in visual arts which makes such things so commonplace that they are expected, taken for granted, barely seen by many. They fail to estrange because such aesthetics are now part of how the illusion of realism – as currently understand by audiences – is achieved.”

I don’t know if I’m reading it right, but this made me think of the spider-robot “bumping into the camera” in “The End of the World”. It’s a bit the viewer maybe doesn’t even notice (I don’t think I did), and if they do, they laugh briefly then forget about it. But if you think about it, it’s a real “What is the reality here?” moment. Because in a realist sense, we’re not supposed to think there’s a camera in place on Platform One. On the other hand, there’s not a spider-robot in the studio, because they got CGIed in later. This is the new production team deliberately homaging a moment from “The Web Planet” that probably had the original production team tearing their hair out!

And it passes largely unnoticed, and certainly unalienating. A spider-robot bumped into the camera, well, these things happen, even if they can’t. You might as well question why making CGI light sources look “realistic” means carefully duplicating a camera artefact…

December 16, 2018 @ 12:16 am

I like to claim that the meaning of art is found in the ways it chooses to be unrealistic. At least, I don’t think it’s an accident that my drama consumption is almost exclusively animation and old sci-fi, and almost completely non-American. (American TV being much closer to cinema than the theatrical roots of British or Japanese television.)

Animation has some interesting effects on the ‘realism of form’ thing. I do wonder what the implications are of stuff like Sound! Euphonium having incredibly realistic-looking backgrounds carefully based on real-world locations and depictions of playing which wow music geeks in how everyone is actually pressing down the right valves at the right time, but still highly stylised character designs and the occasional not remotely realistic looking cake. Or KareKano using different animation styles depending on whether its heroine is in “slouch around the house” mode, “model student” mode etc.

December 16, 2018 @ 11:53 pm

On ‘the concentration on fan reception and politics is far more about consumption’ I feel I should mention that much of fan studies concentrates explicitly on consumption, as, for example, in Cornell Sandvoss’s Fans: The Mirror of Consumption. The whole field seems dedicated to the notion that fandom (which in fan studies means ‘the state of being a fan,’ rather than ‘the community of fans,’ as fans themselves use it) is all about the consumption of a fan object.

My attempts to point out fan activity where there is no fan object (such as Furries and tabletalk RPG) are met by blank looks.

There may, or may not, be a political reason underpinning this obsessive insistence that fandom, an affective relationship which may occasionally operate according to logic somewhat unlike mainstream capitalism, in in fact nothing more than a particularly intense form of capitalist consumption.

December 17, 2018 @ 12:17 am

Serious question, then: what is being a fan? That is, in the absence of an object, what defines the difference between a fan and, say, a hobbyist? Is it just a matter of having roots in a particular subcultural history?

December 17, 2018 @ 12:24 pm

Not ‘just’ (as I’ve learned from workshops with fan audiences over the years!). But that’s a big part of it. The ‘original’, ‘literal’ meaning of fan (which originated at the end of the 19th century with US baseball fans, fact fans!) surely is of relatively little importance compared to the vast consciousness of what it means to be a fan which has developed over the subsequent century and a bit.

The difference between a ‘fan’ and a ‘hobbyist’ is a highly subjective area. I used to be involved in a number of fandoms, trading with Doctor Who zines, music zines, SF zines, games zines, personal zines and Diplomacy zines. Even though the Diplomacy zines were called fanzines, many members of that, er, hobby, were more comfortable calling it ‘The Hobby’ rather than Diplomacy fandom. On the other hand many of the perzine editors, despite having no explicit fan object or affiliation, were adamant that they were a part of a nebulous entity called ‘Fandom’. SF Fandom was probably the closest (perhaps because the oldest) avatar of this nebulous Fandom.

April 16, 2019 @ 9:11 am

It took me months to make the time to read this, but I’m awfully glad I did.

As a child I watched Doctor Who and other shows in that twilight state of understanding, where the events are simultaneously “only a TV show” and real — the confusion that puts kids behind the sofa. There was a similar overlap between the “reality” of the events of, say “Pyramids of Mars”, and the un-reality of certain special effects. Sutekh lifts the TARDIS key on its chain, and it’s obviously being dangled from a couple of wires — but, at the same time, it’s being moved by Sutekh’s mental powers. I wonder if Brecht’s estrangement generates a similar overlapping state in the audience?