This is the final of Chapter Three of The Last War in Albion, covering Alan Moore’s work for Sounds Magazine (Roscoe Moscow and The Stars My Degradation) and his comic strip Maxwell the Magic Cat. An omnibus of the entire chapter, sans images, is available in ebook form from Amazon, Amazon UK, and Smashwords. It is equivalently priced at all stores because Amazon turns out to have rules about selling things cheaper anywhere but there, so I had to give in and just price it at $2.99. Sorry about that. In any case, your support of this project helps make it possible, so if you are enjoying it, please consider buying a copy. You may also enjoy my newly released history of Wonder Woman, A Golden Thread. Chapter Four will begin next week.

PREVIOUSLY IN THE LAST WAR IN ALBION: Alan Moore’s first strip for Sounds, Roscoe Moscow, ended after a little more than a year, and was replaced with The Stars My Degradation, a science fiction parody strip…

“The Stars My Destination is, after all, the perfect cyberpunk novel: it contains such cheerfully protocyber elements as multinational corporate intrigue; a dangerous, mysterious, hyperscientific McGuffin (PyrE); an amoral hero; a supercool thief-woman…” – Neil Gaiman

To continue to come up with inventive page layouts and subversive cat gags week in and week out is one thing. To labour excessively on a reasonably humorous sci-fi parody strip in order to cover up inadequate artistic skills is another.

|

Figure 130: The Stars My Destination was

first serialized in four issues of Galaxy in 1956 |

In this regard there’s something strangely apropos in Moore’s choice of parody subjects in The Stars My Degradation. The title – indeed the entire opening rhyme – is a parody of Alfred Bester’s 1956 novel The Stars My Destination, originally titled Tiger! Tiger!. Bester is very much a science fiction fan’s science fiction writer – one who enjoys rather more renown within science fiction fandom than without. To name The Stars My Destination as one’s favorite science fiction novel is not in the least bit controversial – it’s widely and repeatedly cited as one of the best. But it is not a particularly famous book outside of science fiction circles. Unlike writers such as Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, and Arthur C. Clarke, whose work became influential and widely known outside the sci-fi community, Bester remains at once obscure but terribly well-respected: Samuel Delany, William Gibson, and Michael Moorcock have all identified it as their favorite science fiction novel.

|

Figure 131: Gully Foyle is my name

Terra is my nation

Deep space is my dwelling place

The stars my destination

(Howard Chaykin, 1979) |

On one level, The Stars My Destination is a fairly straightforward pulp-style novel. It was serialized over four issues of Galaxy, and features the sort of episodic content familiar to such material. What elevates it is the character arc of its protagonist, Gully Foyle. Foyle is not a well-rounded character in the conventional, literary sense. In fact, he is largely a cipher. At any given time his motives are utterly transparent and simple, and he is typically single-mindedly consumed by them. At first Foyle is seen floating in space, described as “one hundred and seventy days dying and not yet dead” and as struggling to survive “with the passion of a beast in a trap.” When a passing spaceship ignores his distress call he changes, becoming bent on revenge. Over the course of the novel his motivations shift and evolve further – he learns to act as a socialite, renaming himself Geoffrey Fourmyle, eventually learning to control his emotions so that the remnants of an extensive facial tattoo of a tiger he is forcibly given early in the novel stop appearing on his skin. Eventually he has a quasi-mystical experience as he’s trapped in a burning building, causing him to teleport throughout space and time (limited teleportation, called jaunting, being one of the basic conceits of the novel) while burning, before finally becoming a sort of cosmic holy man, living peacefully in the stars to see if mankind ascends to his level.

In other words, while the novel lacks any sort of intricate character work, it still has a clear character arc that grants a greater sense of unity and development than many contemporary novels. Its central conceit is that the various bits of sci-fi technology Bester posits allow a single man to go from an animalistic creature driven only by his desire to survive to a figure of profound spiritual enlightenment. This is compelling in its reach, and presages the yet-to-emerge new wave of science fiction that Moorcock and Ballard would eventually exemplify, where science fiction concepts were not merely logic games about hypothetical technology, but metaphors for psychological and sociological phenomena, more interesting for the ways it can comment on human consciousness than for the comparatively banal questions of how imaginary science works.

|

Figure 132: Gully Foyle’s synesthetic

experience (Howard Chaykin, 1979) |

In this regard what is most interesting in The Stars My Destination is the section in which Foyle is jaunted through space and time, intersecting his past timeline. Through this period he experiences synesthesia, such that “the cold was the taste of lemons and the vacuum was a rake of talons on his skin. The sun and the stars were a shaking ague that racked his bones.” His journey here is described as “hurtling along the geodesical space lines of the curving universe at the speed of thought, far exceeding that of light. His spatial velocity was so frightful that his time axis was twisted from the vertical line drawn from the Past through Now to the Future. He went flickering along the new near horizontal axis, this new space-time geodesic, driven by the miracle of a human mind no longer inhibited by concepts of the impossible.” This vision of traumatic enlightenment prefigures the visions of eternity that Morrison and Talbot played with in Near Myths, to say nothing of Moore’s future work like The Moon and Serpent Grand Egyptian Theatre of Marvels and Promethea.

Throughout it, however, is the peculiar image of Gully Foyle himself. The tiger tattoo and his incandescent jaunt through space and history are clearly drawn from the same poem that Bester took his original title from: William Blake’s “The Tyger,” the first stanza of which provides the novel’s epigraph. The poem is Blake’s best known, and comes from Songs of Experience, the counterpart to his Songs of Innocence. The two volumes provide interconnected poems, with the earlier Songs of Innocence presenting a lilting, pastoral view of childhood, while the later and more bitter Songs of Experience reveals scenes of crushing poverty and cruelty. “The Tyger” is Songs of Experience’s retort to “The Lamb,” a pleasant bit of verse reflecting on the eponymous ewe’s “clothing of delight, / Softest clothing wooly bright,” and how it’s a reflection of Christ’s kindness.

|

Figure 133: “The Tyger” (William

Blake, 1794) |

In contrast, “The Tyger” provides an image of monstrous divinity: a beast of fire and rage. Blake’s verse at once recoils from the beast and stares at it in awe, but more importantly at whatever divinity created such a terror, asking “In what distant deeps or skies. / Burnt the fires of thine eyes? / On what wings dare he aspire? / What the hand, dare sieze the fire?” The Tyger itself is a terror, yes, but merely a mundane one of sinew and flame, in the end no different than the tragic poverty Blake depicts elsewhere in Songs of Experience. The true terror is the monstrous god that created this beast, and the terrifying order of things in which it exists, a sentiment expressed in the poem’s penultimate verse, which asks if “When the stars threw down their spears / and water’d heaven with their tears; / Did he smile his work to see? / Did he who made the Lamb make thee?”

And yet through all of this Blake’s sense of awe and wonder at this divinity comes through. “The Tyger” evokes the horror of God, but it never once moves to reject God for these horrors. Instead the terrified awe becomes a new form of worship. This is, in the end, the point of The Stars My Destination: not merely that Foyle has this visionary experience, but the monstrous world of corrupt corporations and human depravity that steadily moves him from his innocuous beginnings to his eventual enlightenment. What is striking about The Stars My Destination is that enlightenment is treated as monstrous phenomenon, and yet also as a desirable one. And, of course, that Foyle attains it by moving through the world, in a social progression from base animal to social creature to enlightened being.

On the surface The Stars My Degradation is a grim and cynical inversion of this. The social order that Dempster Dingbunger encounters does not provide him any sort of enlightenment, but an endless humiliation and, as the title puts it, degradation. It is the work of someone who is barely clawing a living together, and who has suffered mightily at the hands of authority figures such as the headmaster who expelled him in 1971, who not only expelled him but who hounded him for years afterwards, writing what Moore describes as “the anti-matter equivalent of references” that went so far as to accuse him of sociopathy, resulting in him having to take degrading jobs like his job at a tannery, which he describes, saying “we had to turn up at 7.30 AM and drag these blood-stained sheepskins out of these vats of freezing cold water, blood, and various animal by-products. Many were the happy hour that we had throwing sheep’s testicles at each other.” Or, as he put it elsewhere, “the job down at the skinning yards where men with hands bright blue from caustic dye trade nigger jokes.” Even eight years removed from that, as he navigated the beginnings of a freelance artistic career, trying to avoid the threatening gaze of Thatcher’s newly elected government and its savage cuts to the social safety net he was still dependent on, the sense of a world whose machinations led not to any sort of spiritual enlightenment but towards suffering, disappointment, and being cheated by the people you trusted would have been clear. Hence Dingbunger’s world of kangaroo courts and forced labor, where no matter what apparent victories he wins in surviving he will never encounter anything but celestial degradation.

|

Figure 134: William Blake’s critique

of exploitative labor is no less savage

in the Songs of Innocence version of

“The Chimney Sweeper” (William

Blake, 1789) |

And yet in practice Moore was, unbeknownst to him, on the other path – the one mapped out in Bester’s original. It is not that he was wrong about the brutal cruelty of the world, any more than Blake was wrong when he described the crushing poverty of young chimney sweepers, describing one as “A little black thing among the snow: / Crying weep, weep. In notes of woe!”, and savaging those who “praise God & his Priest & King / who make up a heaven of our misery.” As Moore makes his way through the landscape of the War he will encounter far more instances of abuse and exploitation. And yet in hindsight The Stars My Degradation is a rung on a ladder that would lead Moore from the impoverished desperation of a freelancer to the heights of artistic genius and, for that matter, financial success. In time he would find himself staring into the same monstrous light gazed upon by Blake and Foyle. Like both Blake and Foyle, his path into that light wound through the material cruelty of the world. But it also wound past it. Moore kept working, producing comics at a furious rate. In time his income from his work for Marvel UK, IPC, and Dez Skinn’s Warrior provided enough income that he could drop the time-intensive The Stars My Degradation, but even then he replaced it with even more work. Even while doing The Stars My Degradation he took on other jobs, writing a variety of reviews and interviews for Sounds.

But it would be a mistake to treat Moore’s eventual success as some supreme act of individual will, just as it would be to treat Blake’s artistic career as the product of a wholly independent man, or, for that matter, to treat Foyle’s enlightenment that way. At a key moment in Foyle’s space-time jaunting he encounters Robin Wednesbury, a one-way telepath he’d encountered several times previously in the novel, and, crucially, treated with shocking cruelty on more than one occasion. And yet Robin, when she meets the jaunting and burning Gully Foyle, explains to him what’s happening and tells him what he needs to know in order to save himself and escape the burning building. This establishes an essential point in Bester’s narrative, which is that for all that the cruelty of the world sets Foyle on his path, Foyle is in no way a completely isolated individual. Indeed, he depends on a variety of friends and allies, all of whom work together to get him out of the burning building.

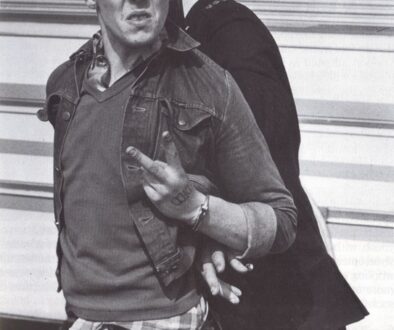

|

Figure 135: Axel Pressbutton dies of a fatal laser blast/orgasm

at the end of his first appearance in Three Eyes McGurk and

his Death Planet Commandos (Steve Moore, as Pedro Henry,

and Alan Moore, as Curt Vile, 1979) |

Moore’s ascent from a grubby £45-a-week freelance existence to becoming one of the most successful and acclaimed artists of his era was similarly dependent on a variety of friends and helpers. Most significant of these, early on, was his friend Steve Moore, who he first met in the late 1960s, and who provided the model for his eventual transition into being a writer instead of a writer-artist. Steve Moore, in fact, is the writer behind the Pedro Henry pseudonym, and stepped in to help Moore manage his workload by plotting the final year of The Stars My Degradation. But Steve Moore’s influence is not just limited to this late game assist. One of the major characters of The Stars My Degradataion is Axel Pressbutton, an extravagantly violent cyborg who made his first appearance in a strip called Three Eyes McGurk and his Death Planet Commandos, another early non-paying gig Moore did for the minor British music magazine Dark Star. Moore had been working on a strip called The Avenging Hunchback, a superhero parody, but the second installment of that strip was lost when the editor’s car was stolen, and Moore was too disheartened to repeat all of his delicate stippling. Accordingly, Steve Moore stepped in to help his friend, writing “Three Eyes McGurk” as a replacement strip, and including the Pressbutton character. (Moore in fact based Pressbutton’s visual design on Lex Loopy, a Lex Luthor parody designed for The Avenging Hunchback.) “Three Eyes McGurk” ended up being Moore’s first American publication, getting a reprint in a 1981 anthology edited by Gilbert Shelton, and Moore went on to incorporate the character (earlier in his life, as he dies at the end of his original appearance) into The Stars My Degradation.

As mentioned, it was Steve Moore who taught Alan Moore to write comics scripts, and whose career was the early model for Moore’s transition away from being a writer-artist. But perhaps the most crucial intervention Steve Moore made in Alan Moore’s early career was utterly pragmatic, as he tipped Moore off to an imminent job vacancy at Marvel UK, thus giving Moore his first job as a pure writer. [continued]

NEXT TIME: Alan Moore finds himself writing two of the biggest sci-fi properties in the world, storms off a job in protest for the first of many times, and meets the man he credits with ruining his life. It’s Chapter Four of The Last War in Albion: Alan Moore’s Doctor Who and Star Wars Work.

November 7, 2013 @ 12:58 am

Oops, I stepped on your toes slightly by revealing the identity of Pedro Henry in the comments of Part 16.

I never realised before how The Stars My Destination prefigured the character arc and information overload ending of 2001: A Space Odyssey until I read your précis of the novel. Bester also did something Moore was famous for: building a new piece of art from the fabric of old art (although some would accuse him of stealing), as the other primary influence on The Stars My Destination was The Count of Monte Cristo.

November 7, 2013 @ 6:02 am

Tangential comment: The Count of Monte Cristo is also a major influence on Les Miserables (even down to the escaping-in-a-coffin trick). Hugo's "gimmick" is to split the main character of Dumas's novel into two — the unjustly imprisoned/escaped man now risen to post-prison success, and the implacable, indefatigable predator dedicated to retribution — and set one to chase the other.

November 7, 2013 @ 8:19 pm

Not much to say on this part of the chapter, other than I'm looking forward to more- and I want to dig up and re-read my copy of The Stars My Destination, which I haven't read in about 20 years!

November 8, 2013 @ 2:26 am

Very enjoyable entry.