For Sweet Fuck All (Book Three, Part 25: Troubled Souls)

CW: NSFW imagery.

Previously in The Last War in Albion: The late 80s/early 90s anthology Crisis was a politically engaged book for mature audiences that saw early work from a number of prominent figures, among them Garth Ennis.

If I’m a cynic, is being a believer really all that much better? Is never giving in, never compromising, is that really so great? When so many parts of your country have been turned into hell? When three thousand people have died for sweet fuck all? – Garth Ennis, The Punisher

Hailing as he does from Northern Ireland, Garth Ennis is not technically a British comics writer. Nevertheless he is a major figure in the nexus of writers that formed within the blast radius of the War—a secondary figure on the same order as Gaiman or Millar. Ennis entered comics as a young hotshot; he had just turned nineteen when he landed Troubled Souls in Crisis, his first professional work. Nevertheless, he immediately joined the upper echelons of the scene, charming Moore on the train ride to Angoulême a few weeks after is birthday in 1989 and commencing what would be a lifelong friendship. (Ennis recalls Moore advising him early on to “own what you create. Don’t let them do to you what they did to our generation,” which is probably more hindsight than Moore would have treated his career just two years after Watchmen, but comports with Moore’s own memory of “ giving him dire warnings about what he should expect in the comics industry.” Moore, in any case, provided a blurb for the trade paperback of Ennis’s second Crisis story, True Faith, describing it as “a fresh and original work, the power and charm of which last long after one closes its pages.”) Troubled Souls goes a long way towards explaining this meteoric ascent; it is, quite simply, a spectacular work. In one sense it is, like Sticky Fingers, a slice of life comic. But a slice of life comic is typically defined by its normality, while Troubled Souls was nothing of the sort. It was, instead, a comic about life during the Irish Troubles.

In one sense the Troubles can only be understood in a larger historical context. This begins roughly in the 12th century when the Normans conducted their first invasion of Ireland on the nominal pretext of assisting the deposed King of Leinster Diarmid mac Murchadha, but more generally because Ireland was a big island full of resources right near Britain and conquering things like that is what 12th century Normans did. This commenced a period of several centuries in which English influence in Ireland largely waxed and waned over the next few centuries until 1542 when the Irish Parliament acceded to the English demand to become the Kingdom of Ireland, with the British monarch on the throne, a request made both out of concern over the growing rebelliousness of the Irish and the need to consolidate newly Protestant English control over Ireland separately from the Catholic Church’s authority.

In 1609 a wave of colonization granted large swaths of land in Ulster, to the north of Ireland, to English and Scottish Protestants. A series of conflicts followed as Ireland became a particularly brutal battleground in the English Civil War, resulting, in some estimates, in the death or displacement of nearly half of the Irish population. In the wake of these wars the Penal Laws were passed, establishing Anglican Protestant control over Ireland and severely curtailing the rights of Irish Catholics and Protestant dissenters. In 1801 this reached its apex with the Acts of Union, creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

In the 19th century, Ireland remained relatively un-industrialized, used by England as an agricultural producer. A brutal mid-century famine resulted in a wave of Irish immigration to the US as the Irish economy collapsed. The wake of this produced the Land War, a rebellion on the part of tenant farmers largely backed by the Irish Catholic Church. This gave way to an Irish nationalist movement that gained power in the late 19th and early 20th century. In 1913, with a bill establishing Home Rule on the brink of passage, a militia known as the Ulster Volunteers formed out of concern that self-governance would favor the Irish Catholics as opposed to the Protestant descendents of the 17th century colonists. In response, nationalists formed the Irish Volunteers. A bill establishing Home Rule finally passed in 1914, but implementation was immediately delayed by the outbreak of World War I. This sparked the Easter Rising in 1916 as a group of nationalists took over Dublin and proclaimed an Irish Republic. The British crushed the rebellion with overwhelming force in six days’ time, swiftly executing the leaders a few days after.

This proved counterproductive to the British cause, instead sparking a new fervor in the Irish independence movement. A 1918 election saw Sinn Féin, the main nationalist party, sweep to a massive majority, and it swiftly proclaimed independence. Three years of guerilla warfare followed before a treaty at the end of 1921 saw Britain concede Irish independence, but with a clause allowing Northern Ireland to opt out of the process, which it quickly did, leading in 1922 to the partitian of Ireland between the Irish Free State, later the present-day Republic of Ireland, and Northern Ireland, which remained part of the United Kingdom. This resolved little in practice, as a significant portion of the Northern Irish population were Irish Catholics who identified as Irish rather than British and would have preferred to be part of the Irish Free State. And so Northern Ireland hardened into a bitter schism between Protestant unionists and Catholic republicans. The former group had political control and so continued the centuries long marginalization of the latter group, establishing an electoral system that allowed them political control even of predominantly republican areas.

In the 1960s these tensions began to boil over once again. A civil rights movement pushing back against anti-Catholic discrimination was bitterly opposed by hardline unionists such as the Ulster Volunteer Force, which commenced a bombing campaign in 1966 targeting Catholic schools and homes and shooting numerous Catholic civilians. In 1969 the situation descended to riots, most notably the three day Battle of the Bogside in Derry, which saw the British Army deployed to put down the republicans. Things escalated quickly from there, with bombs and shootings conducted by both sides. In 1972 the British Army opened fire on a rally opposing the policy of internment without trial, killing fourteen in what became known as Bloody Sunday. The Irish Republican Army, meanwhile, began its own campaign of bombings and attacks on British troops. Five hundred people would go on to die that year alone. This sparked decades of what were essentially a civil war that killed more than 3500 over the decades it ran, a majority of them civilians, before a peace settlement was finally reached in 1998.

In another sense, none of this history matters in the slightest. This is not to say that centuries of British exploitation of Ireland didn’t happen, that the resentment and anger of marginalized Catholics was unjustified, or for that matter that the IRA’s campaign was not, in fact, a campaign of brutal and murderous terrorism in its own right. It is simply that these facts did not especially matter to the Troubles as they were experienced by the vast majority of people, which was not as a series of historical events driven by abstract forces but a day-to-day reality of life that happened to actual people. Belfast was, for decades, a city under military occupation, barbed wire barricades, and mandatory checkpoints. Eight foot high iron “peace walls,” sometimes miles long, were constructed to separate neighborhoods. Bombs and gunfights in residential areas were simply a fact of life for people, the vast majority of which, whatever opinions they might have on the underlying conflict, were in no way participants in it. For many of these people the Troubles were simply the thing that had killed their friend, deafened their mother with a bomb blast, gotten their brother shot on the way home from the pub, or left their corner shop a pile of rubble. Rightness and wrongness were irrelevant. For most people, there was only the awful human cost of it all.

Troubled Souls exemplifies this. It is a story of ordinary people whose lives are deformed by the brutal and often absurd cycle of violence that surrounds them. Its story concerns a young man, Tom Boyd, who finds himself caught in an escalating chain of events surrounding an IRA fighter named Damien. It begins in the pub when Damien, looking to ditch a gun before the police interrogate him, dumps it on Thomas’s lap, correctly guessing he’ll be too scared to say anything. From there Damien blackmails/threatens him into helping plant a bomb, which Tom gets caught in the blast of while trying to save the girl he fancies. This leads to Damien being ordered to take Tom out as a loose end, an order that proves a bridge too far and sends both of them into hiding.

All of this is told with a quiet understatement emphasized by John McCrea’s restrained style, which uses a simple and unadorned line for outlines and then does all the shading through painted colors, giving everything a softly sunlit tone within which the occasional outbreaks of gruesome violence stand out with real horror. Ennis’s approach to the storytelling, meanwhile, is full of warmth and sentiment—he has a fundamental sense of compassion for his characters, understanding all of them, even Damien, as ordinary people caught up in a cycle of futile violence. This is balanced, however, with a clear-eyed sense of the horror of his subject. Ennis depicts with a brutal directness the corrupt and callous way in which the leadership of both factions operated, noting the cruelly ironic reality that the two sides had numerous high level contacts with each other, often turning to the other side in order to eliminate members of their own faction viewed as problematic. It is a stunning mixture of compassion and disgust for the whole cruel and brutal business of turning a country into a war zone.

It is once Tom and Damien go on the run that the story becomes properly extraordinary. Drinking by candlelight they talk. “We should hate each other and ourselves,” Tom narrates. “And we’re friends. What we’ve done is so similar. What’s been done to us is so similar. So we try and talk about something else. After all, friends do. Friends talk about when they were wee, or their favorite team or that band they always wanted to form… How ridiculous this all is, I think. But it’s happened. Against all the rules and all the conventions of life in this sick wee country… and if we can be friends, I think to myself… if we can do it, surely everyone else can? But I’m drunk, so I don’t see how bloody childish that is.” And then, the next day, desperate to return to his normal life, Tom runs away from Damien, who chases him down. As Tom cowers, Damien attempts to show him that his gun is unloaded, at which point two soldiers shoot him dead.

It’s a cruel and bitter ending—a heartbreaking resolution that underscores the pervasive and inescapable nature of the Troubles and the sheer pointlessness of the violence it brings. There is no move towards redemption—the story ends with Tom too horrified by what he’s done and leaving Belfast and the normal life he got his friend killed to protect. There’s just a bitter sadness at the broken cruelty of it all. It is an absolutely stunning debut that immediately establishes Ennis as a major talent even within a generation of writers that was full of them.

Ennis’s subsequent Crisis work, however, would complicate the picture. Perhaps the most revealing is For a Few Troubles More, his direct sequel to Troubled Souls. Where Troubled Souls was a moving and nuanced personal story, For a Few Troubles More is a broad slapstick comedy focused on two minor characters from Troubled Souls—Tom’s friend Dougie and Ivor “Hopalong” Thompson, a boorish fellow described in Troubled Souls as being “as ignorant as a sack of arseholes on the way to a shitein’ match” who steps in as Dougie’s best man following Tom’s departure.

As that description of Ivor suggests, the tone of For a Few Troubles More is one of puerile excess—its idea of a great gag is a character being given laxatives before his honeymoon, resulting in a page of gurning facial expressions and outlandishly lettered SPALOSH sound effects. It is not that comedy is somehow a lesser form than serious and probing examinations of the wide-ranging effects of cultural violence. But there is something unseemly about a direct sequel in the same magazine that moves a story from a moving meditation on violence to a gross-out epic. For a Few Troubles More does not have a lot to say about the world beyond “diarrhea is hilarious,” and positioning it as a sequel to Troubled Souls has an effect that is not entirely dissimilar to that of appending Doomsday Clock to Watchmen, except that it’s the same guys doing both comics. That For a Few Troubles More went on to spawn a series of further adventures of Dougie and Ivor under the banner Dicks, initially at Caliber Comics and later, inevitability, at Avatar, where Ennis and McCrea’s comedy of the grotesque could find full realization in stories where Dougie and Ivor fight demons and dress up as dildo-throwing superheroes. It’s amusing, in the way that late career projects in which rightfully acclaimed creators have a lark often are, but it’s hard to escape the sense that Troubled Souls is diminished by the fact that its most enduring legacy is Dicks.

The aesthetic of For a Few Troubles More is in no way an outlier in Ennis’s career, though, Another piece of his Crisis work was a series of one-offs under the banner Suburban Hell. These offered a satire of suburban comfort—the debut, “The Unusual Obsession of Mrs. Orton,” was essentially structured like a Future Shock—a woman becomes obsessed with trying to catch the person whose dog keeps pooping on her yard, spending day and night staring out the window until she’s eventually carted off to an asylum, still muttering, “Any day now. Any day now I’ll get him.” But the underlying sense of humor is clear both in the subject matter of dog turds and the ending, as a man walks his dog past the now abandoned house and encourages him to take a dump on the yard.

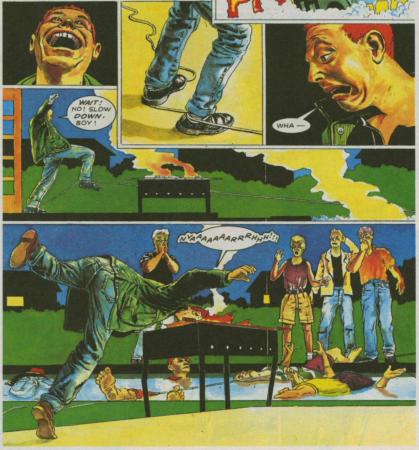

Ennis revisited this fellow in “A Dog and His Bastard,” a story in the Revolver Horror Special, chronicling yet more scatological escapades of the pair before giving the man a comeuppance when his dog pulls him down face first onto an open grill while he’s trying to sabotage a teenage party. And the further installments of Suburban Hell continued in the same vein; The Ballad of Andrew Brown” was an illustrated poem about a boy’s desperate need to shit, for instance. Not all of the installments were quite so fecal, but they all shared a similar sense of glee in gratuitous transgressiveness for its own sake. Some, such as “Light Me” towards the end of Crisis’s run, had worthwhile points to make about war, violence, and masculinity alongside its sniggering glee at having its unpleasant narrator describe work as an “office full of yuppie faggots.” But the overall aesthetic is unmistakably one of a performative transgressiveness reveling in how edgy it’s being. It’s adult comics in the most childish sense imaginable.

Ennis’s career would see him repeatedly indulging in this same basic style of humor. Sometimes this was done to reasonable effect. True Faith, for instance—the story he did for Crisis between Troubled Souls and For a Few Troubles More—is both a story that delights in shock and offense and tells a moving and emotional story that compares to Troubled Souls. Its central plot concerns Terry, a toilet cleaner whose family dies suddenly and who thus swears that he’s going to kill God, beginning a campaign of burning down churches and shooting religious figures in an effort to force God out into the open. It’s ostentatiously confrontational and vulgar—Terry repeatedly refers to God as a “blockage in the S-bend of the world,” including while violently drowning a man in a baptismal font. But it’s also a comic about grief and social isolation with no shortage of moving scenes. The result is an effective combination of Ennis’s two registers—something that, much like The New Adventures of Hitler, undoubtedly has a gleeful and performative edginess, but that is capable of using it to tell important stories that wouldn’t work without it.

This aspect of Ennis’s style—what would eventually come to be called edgelording—was a significant part of the late 80s/early 90s British comics renaissance. This is unsurprising—a major fuel of the boom was the sudden demand for British writers in the American market, where one of the primary influences and models was Frank Miller, who had a similar sense of humor, especially when left to his own devices. (Consider his contribution to AARGH! for instance.) And more generally, it was simply an obvious development when a British market that had for almost a decade been defined by the brashness of titles like Action and 2000 AD turned towards more explicitly “adult” comics. If your starting point is Kids Rule OK! or Judge Dredd and then you make a move towards allowing adult content then getting something like For a Few Troubles More or Suburban Hell is more or less inevitable, a fact implicit in the fact that “The Unusual Obsession of Mrs. Orton” was basically structured like a Future Shock.

Perhaps the most obvious implementation of this aesthetic in the British market at the time was Toxic!, a weekly published for seven months in 1991 by a publishing company called Apocalypse Ltd., formed by Pat Mills, John Wagner, Alan Grant, and Kevin O’Neill, all mainstays of 2000 AD. With a banner on the first issue proclaiming “The Comic Throws Up!” and an inside page that declared the magazine “only interested in real sickos,” it was a magazine determined to live or die on its ability to appeal to teenagers who really liked vomit jokes and stripes called Sex Warrior. It was not that the magazine was bad per se—this was, after all, the same Pat Mills who had just done career best work with Third World War, and strips like lead feature Marshal Law, which saw Mills and O’Neill collaborating, were legitimate classics in their own rights. But it was profoundly juvenile in its presentation—a comic that aimed to get by on nothing more than a schoolboy gross-out aesthetic even when it had more available to it. (One could also note the meteoric popularity of Viz magazine around this era—a profane satire of The Beano and The Dandy whose explosive sales were no doubt an influence on this wave of more adult British comics, but that largely existed in its own bubble with no creative overlap with the War.)

At the apex, or perhaps nadir, of this aesthetic sat Mark Millar. [continued]

October 7, 2021 @ 8:15 am

“the overall aesthetic is unmistakably one of a performative transgressiveness reveling in how edgy it’s being.”

Nice.

Ennis sets my teeth on edge. There’s a real talent there. But he comes across as twisted at a deep level. Not so much the gross-out stuff as the fascination with masculinity and violence, particularly the fetishization of the Hard Man. It might not seem surprising that a Northern Irish writer should be fascinated with the Upright Man Of Violence, but it actually is kind of weird given that Ennis is obviously smart and wise enough to see that Hard Men brought abomination to Northern Ireland, over and over again.

And yet he may be the one guy most responsible for the proliferation of Punisher skulls as an alt-right symbol across North America. Not that he ever supported it himself (I have no idea what his position is), but if there’s one writer who moved the Punisher from being a throwaway C-list character to one with visceral and lasting appeal, Ennis is the man. In one sense, it’s nothing more than what other Invasion writers did with Swamp Thing, Sandman, Animal Man et al. But nobody’s putting a Swamp Thing decal on their pickup before they go out to run down Black Lives Matter protesters.

Again, the edgelording is grafted on to a real talent. The last thing I read of Ennis was his “Code Pru” serial in Cafe Paradiso. That’s a very slight and minor work, about EMTs working the supernatural side of town. But by damn it made me laugh out loud (the Outlander / Highlander / Terminator story. “Ah won’t be coming back.”) But of course he had to include a shit demon and some Grand Guignol body horror. By his standards it was very mild stuff, but it still made me sigh. Like… could you just /not/?

Anyway: I did not know that Ennis and Moore were so friendly. Did they remain so?

Doug M.

October 11, 2021 @ 8:37 am

Also: I only just made the connection between V for Vendetta masks and Punisher decals.

It’s quite easy to imagine a car with the latter running down people wearing the former. Not just for kids anymore!

Doug M.

October 11, 2021 @ 10:21 am

My intro to Ennis was his run on Hellblazer, which contained both his tendencies outlined here. I then saw a Vertigo one-shot, Heartland, with featured characters he obviously cared about which he’d used in Hellblazer and told a slice-of-life story of early Celtic Tiger-era Ireland. It was great; vanished without a ripple.

After, every Ennis comic I read was characterized by juvenile cruelty and a raging contempt for his imagined audience of comics readers, and a fascination with hard-man asshole masculinity. This visible in Goddess and The Boys, the latter a comic I’ve barely looked at after establishing it was more of the same.

These qualities absolutely ruined Preacher, which I finally read last year and was just the most frustrating exercise in pointlessness, completely wasting a potentially interesting premise and a handful of good character beats and ideas.

I found the tv show of The Boys subtly changes the focus and tenor of the comic and is superior, imo.

October 11, 2021 @ 10:24 am

Douglas Muir, I should have read your comment before posting as you stated everything I wanted to say better than I did. But I still would have commented cause I just needed to get that out. Such a talent, wasted on hateful crap.