Economic Miracles

This is my Timelash II stuff on the subject of Graham Williams’ tenure as producer… it’s a bit thin because I’ve either posted about several stories from this era elsewhere or because I’m planning to. Also, to be honest, some of the stories simply don’t yield much grist for my mill. That isn’t to knock the Williams era, which contains some of the most politically interesting Who stories ever made (which is partly why they needed – or need – posts all to themselves). Notice, for instance, how the stories glanced at below seem obsessed with fuel, economics and questions of prosperity vs. austerity… s’what comes of making Doctor Who in the context of the late 70s I guess…

I’ve written about ‘Horror of Fang Rock’ here and ‘Image of the Fendahl’ here.

‘The Sun Makers’

This is from elsewhere on this blog, but it’s part of a wider article. I thought it could tolerate repeating… especially since ‘Sun Makers’ is a favourite of mine, for reasons which should be obvious. I don’t think, by the way, that this story has ever been more relevant than it is now.

Some other idiots have occasionally argued that ‘The Sun Makers’ is a right-wing allegory because it depicts a tyrannical state and rails against taxes. Well, that’s fine if you’re dumb enough to buy the bullshit lie that conservative politics really is all about defending personal liberty from big government and punitive taxation. In fact, ‘The Sun Makers’ couldn’t be clearer about its political sympathies (even if you stick your fingers in your ears during the playful misquoting of Marx). The tyrannical state in this story is the Company. They are effectively one, or the Company exercises such control that they might as well be. This isn’t a big state stifling the liberty of free enterprise and free consumers. This is a big state as a vehicle for corporate domination. The Company is a private concern, engaged in “commercial imperialism”. The Company has, essentially, carried out a hostile takeover of the government. This is one big state that’s been privatised.

The icons of modern conservatism (i.e. Reagan, Thatcher, Bush, Bush II) are usually, for all their populist anti-government rhetoric, ultra-statists. They might reduce bureaucracy here and there (usually by cutting public services, etc.) and deregulate business, but they always strengthen the state’s machinery of enforcement, regulation, control and surveillance of its citizens, i.e. the poor schmoes who do all the work get spied on and arrested more. Meanwhile, we have de facto economic planning in the hands of radically undemocratic and monolithic organisations. We just call them corporations, but they act like states within states. And they get more and more powerful all the time.

Was the Iraq war a state affair? Well, the costs were pretty much covered by the state (i.e. by the American taxpayer) but the opportunities and profits were tendered out to the companies that swarmed in like vultures. Neoliberalism wants to turn the state into a heavily armed enforcement service that monitors and controls and taxes the population while acting as a munificent pimp for corporations, farming out every other task of the state to them, garnished with massive subsidies (i.e. corporate welfare).

The state gathers and the Company collects.

This is pretty much what Bob Holmes wrote about in ‘The Sun Makers’. His income tax bill seems to have got him thinking about the future of neoliberalism. Strange but true. Maybe he was looking at Chile and General Pinochet’s great experiment in merciless Chicago school ultra-monetarism, which he inflicted on his people via brutal repression. How else did he manage to write a Doctor Who story in 1977 that can be read as a companion text to The Shock Doctrine by Naomi Klein?

But the key thing is the way the workers are portrayed as changing in the course of the struggle. The Others are clearly former workers who’ve opted out. Mandrel’s grade status and former workplace even become plot points. Cordo is the lowest of the low; a timid, despairing and bankrupt drudge, the son of a lifelong corridor sweeper. But they end up uniting across the grade barriers, across their former differences. The Others go from cowardly hiding and petty criminality to leading a general strike. Cordo goes from contemplating suicide to jubilantly leading a revolution. Bisham is an executive grade whose moment of curiosity lands him in detention; initially, he lies back and accepts his doom.. but he ends up uniting with B and D Grades to topple the government. The workers with hand and brain.

Okay, they need the Doctor to get them started, but in this story the Doctor is almost like a personification of Information itself. He tells them things. He makes them curious. He makes them angry. He poses the right questions. He turns off the gas that makes them anxious and passive (surely this is thematically linked to his taking over the TV station and the news service?) and thus gets the ball rolling. It isn’t long before he wanders off with Leela and leaves the united workers to pursue the revolution on their own.

The Doctor’s role as catalyst notwithstanding, this is a full scale workers’ revolution. Moreover, it’s explicitly linked to industrial action in the scene where Goudry and Veet incite the strike. It’s idealised, sure, but the portrayal is not without sceptical irony or some healthy moral ambiguity. Mandrel’s former colleagues Synge and Hackett obviously join the revolution from fear rather than immediate enthusiasm (though they seem to end up happy enough to help), and Marn simply switches sides when she sees which way the wind is blowing.

And then we have the matter of the Gatherer and his little tumble… Well, you can wring your hands about him if you like. I have to do my own tax return so, frankly, I’m not feeling merciful.

‘The Ribos Operation’ is examined in scarily extensive detail, here.

‘The Pirate Planet’

There is a satirical aspect to Douglas Adams’ debut Who story which anticipates the satire inherent in much of Hitch Hiker’s… but whereas Hitch Hiker’s presents a kind of farcical search for God and/or meaning in a universe of comic incompetence and small mindedness, ‘Pirate Planet’ seems more directly political in its preoccupations: at times its almost like Adams is having a go at imperialism through the analogy of piracy.

In ‘Pirate Planet’, Zanak is a culture of indolent and complacent and unquestioning people who kick jewels around their streets whenever their leader simply announces a new golden age and the mines just fill up again… and all because their world grabs others, crushes them, sucks them dry of their wealth and then moves on. The people don’t know because they don’t care to know. Rome never looks where she treads, as Kipling put it. You don’t get political comment quite like that in Hitch Hiker’s (at least not until Infinidim Enterprises arrive in the last novel); you’re far more likely to get satire at the expense of bumbling bureaucracy and plodding literal mindedness (one of the preoccupations of ‘Shada’ a little later, once Adams has found his voice).

In ‘Pirate Planet’, a young man with lots of talent is writing his early, angry stuff… and instinctively fitting in with the ethos of a series that almost reflexively critiques Power in moral terms. Trouble is, Adams is rather too flippant to quite make this story work as a polemic… though he is plainly influenced by Bob Holmes’ way of creating witty and knowing stories that let political comment ride along happily with jokes (i.e. ‘Carnival of Monsters’ and ‘The Sun Makers’).

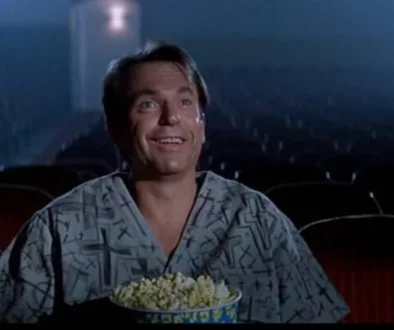

Still, it contains one of my all-time favourite one-liners from Who. Asked if he thinks it’s “wrong” for mines to just fill up with minerals all by themselves, the Doctor replies: “It’s an economic miracle; of course it’s wrong!”

Tom Baker (in one of his greatest late performances) both revels in the smartass comedy and latches onto the underlying seriousness of some aspects of the story. By doing so, he creates an opportunity for himself to turn his great ‘angry scene’ into a moment when, for all the multicoloured glitz and jokey dialogue, he portrays a man genuinely aghast at a crime almost too awful to comprehend. And it’s riveting stuff.

‘The Power of Kroll’

Robert Holmes might’ve been pissed off about having to write about a very big monster, but he was (apparently) even more pissed off about the treatment of Native Americans, racism and big business exploiting the environment. This could have been disastrous if it weren’t for the fact that Holmes is also intelligent about these things. Nothing is all that simple in this story.

The Swampies (or the People of the Lakes, if we’re being PC about it) are more than just victims. We are invited to sympathise with them and direct parallels are drawn with the plight of Native Americans when the Doctor calls their moon a “sort of reservation”. Now that their moon looks commercially exploitable, they’re liable to be forcibly evicted again. But, while clearly the victims of an historic injustice, they’re not portrayed as particularly virtuous or wise. Unlike the Kinda (who have the whiff of gift-shop dreamcatchers about them), the Swampies are flawed and naive. This is rather refreshingly unpatronising. Ranquin is a blinkered religious bigot who is not above using Kroll as a means of getting his own way. Nor is he above a spot of politically-expedient murder. He even has his own face-saving political myth about the Swampies leaving Delta-Magna of their own accord.

It’s interesting to see how Holmes deliberately makes the humans and the Swampies into mirror images of each other. Thawn and Ranquin are both the same kind of deceitful, callous, bullshit artists. Also, Fenner and Varlick are similar types. Both are happy to sanction killing when they disapprove of the victim, but neither is without conscience. They are both troubled by their leader’s behaviour but grumble and procrastinate while still obeying.

The treatment of racism is also intelligent. Thawn is clearly a racist but, when accused of hating the Swampies by Fenner, he denies the charge and simply restates his economic imperatives. This is right on the nail. The motivations behind all organised persecution of minorities is always fundamentally economic. The supposed ethnic and cultural difference of Africans was merely a pretext that was fashioned into a political ideology of slavery; the underlying motive was commercial. The supposed savagery and primitivism of Native Americans was simply an ideological justification for imperialistic conquest and theft. Modern racism has its roots in economics as much as in any deep-seated xenophobic impulse. Nobody in ‘The Power of Kroll’ mentions the fact that the Swampies are green (apart from the Doctor, ironically enough) but Thawn is constantly on about the fact that they’re in his way.

Meanwhile, the exploitation of the natural resources of the lake creates an unforeseen ecological effect; the awakening of Kroll is caused by the Refinery raising the lake’s temperature and shooting off orbit shots. I’d hesitate to call Kroll a metaphor for environmental disaster, but all the same… he is a runaway by-product of the refinery.

Also, the nonsense spouted by Ranquin and Varlick’s growing realisation that Kroll is nothing but a big animal, constitutes another poke at religion… though not without putting the Swampies religious narrative within a political context of oppression and alienation, and entirely without portraying them as inherently culturally backward. This guy was a natural radical, whether he knew it or not. To think he used to edit John Bull Magazine! (Sometimes I see strange similarities between Holmes and Orwell. Holmes was a copper, wasn’t he? Just as Orwell was a colonial policeman in Burma.)

Meanwhile, we have Tom Baker giving one of his best performances. No, I’m serious. Is there any moment during his tenure more blissful than his deadpan inquiry to Thawn: “Will there be strawberry jam for tea?”. Watch the way he looks embarrassed when asked stupid (to him) questions about the refinery. Watch him glare at Thawn’s treatment of Mensch and smirk at Fenner’s unironic use of the all-purpose word “progress”. Then there’s the “aren’t you going to say ‘don’t make any sudden moves?’” scene. This Doctor is a bumbling fartaround, a dilletante, a muckabout, a sophomoric clown… but with a deep, ingrained sense of rage at injustice and cant and bigotry. He’s a satirist of the powerful and callous; he allows the despicable to write him off as a looney. This is my Doctor. None of that lonely god rubbish. No burning at the centre of time like fire and ice and blah blah blah. Just a rogue radical, a wry scientist, an activist eccentric. He quite simply rocks.

Yeah, okay, the Swampies look stupid and their chant is rubbish… and yeah, the monster looks utterly fake… and yeah, Episode 3 is nothing but the stupid creeper-execution thing and loads of conversations about “viscosity levels”… but hey, it’s got Philip Madoc in it, for chrissakes!

And its heart and brain are both in the right places. It has possibly the most fair and unprejudiced portrayal of native, tribal people that I’ve ever seen in sci-fi. It attacks racism, capitalism, environmental destruction and religion… and from a radical challenge position rather than just a hand-wringing liberal critique. It contains none of the sentimentalised patronising attitude to be found in, say, Avatar (yeurch), while also containing ten times the anger.

I’m planning to post something seperate and self-contained on the subject of ‘City of Death’.

March 2, 2018 @ 2:16 pm

Economic miracles are an amazing thing. Personal loans for bad credit at http://aupaydayloans.com is one of those miracles!

September 26, 2019 @ 9:43 am

Your content helped me a lot to take my doubts, amazing content, thank you very much for sharing.