Capitalism and the Protestant Reformation

To say that the protestant Reformation is an expression of the rise of capitalism is not to say that you have capitalist Protestantism on one side, feudal Catholicism on the other. Protestantism did not (usually) express the ideology of capitalism in a direct way. It did not enjoy exclusive support from the rising bourgeoisie. Catholicism did not exclusively express the old ideology of feudalism, or take its support exclusively from old feudal ruling classes and their hangers on.

There’s some truth to that picture, but only at the extremes (where, as Bakunin said, we see things more clearly). Calvin’s Doctrine of the Elect is almost suspiciously perfect in how it provides a justificatory ideology for capitalism. (We shall be coming back to this in later parts of the M.R. James series, for which this post is a kind of parenthetical theoretical bookmark.)

Overall, however, that wasn’t how it worked. Catholicism, in many ways, embraced rising commodification, despite being as based in the power of landed property as any feudal aristocracy. Rothbard and Hayek claimed to see prefigurations of their own libertarian free market ideology in the writings of the Salamancan scholastics (this is still an idea that libertarians are obsessed with). Protestantism caught fire partly because it expressed popular disillusion with the very marketisation of religion – the selling of indulgences, the buying of private masses and prayers, the profitability of episcopal sees, etc – that was increasingly seen in the Catholic Church.

Rather, what we see is a very slow and gradual breakdown of feudal economic stability, and the slow accumulation of wealth and power in new and rising sectors, as a result of rising forms of trade and production, which leads to the growth of increasingly wealthy and powerful middle classes, to political controversy and struggle between classes, and thus to centuries of instability and of ideological squabbling over how to make sense of the mixed-up world. A huge part of the instability is caused by the mixture of capitalist and feudal methods. Increasingly marketised, feudal society found its production methods lagging behind its consumption and investment needs. Exacerbated by the insatiable appetites of ruling classes for both conquest and luxury, this was the root cause of multiple interlocking crises which rocked the world of the late middle ages, only accelerating the instability which further accelerated the economic reconstruction. At the ideological level, both Catholicism and Protestantism are trying to understand the instability and reconstruction. They come to be the two great camps in the realignments and renegotiations of religious ideology because of two material expressions of the rising bourgeois system: the revolutions in communication and in government.

A glib answer to the question ‘Why does Protestantism happen?’ would be ‘the printing press’. But this begs the question: why does the printing press happen? It is both cause and result of the development of technical processes, the slow build-up of new technologies within feudalism, and thus of the growth of literate publics who want to read. This rise of literacy and political involvement is an expression of class struggle, itself partly stemming from – and reciprocally causing – the growth of new classes as a result of that slow accumulation of change. It is also related to the revolutions in government of this era, by which I mean the (very) gradual rise of (relatively) stable national states with centralised governments. Bureaucracies need bureaucrats, i.e. literate functionaries. Burgeoning national states need people they can recruit, and the growth of recruitable classes only spurs the process of the burgeoning of national states and bureaucracies.

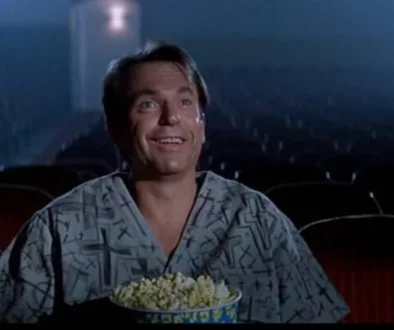

The English Reformation is famously a result of Henry VIII’s marriage problems, but this is an expression of the instability of the feudal system and the rise of the centralised government of a forming national state. The matter of Henry wanting a divorce is the most constantly reiterated subject in popular History in Britain. (The BBC makes at least seventeen television documentaries about it every year… by which I mean they remake the same documentary seventeen more times.) It is usually represented as a purely personal matter of private peccadilloes and lusts ‘causing’ huge historical repercussions. This is one of the reasons it is so endlessly recited. It is the ultimate example of the ‘Great Man Theory’, by which history happens because of the whims and personal foibles of people who are, in some way or for some reason, especially important. And it is also the ultimate example of the ‘Shit Happens’ model, by which history is a random mess of contingency and happenstance. It is, in uniting these two models, the absolutely perfect expression of bourgeois ideology. And that is before you get into the basis of the story in sex, making it possible to represent it via pretty and sexy people in pretty and sexy costumes being pretty and sexy at each other… which sells, for perfectly good reasons.

In fact, however, while Henry’s desire to divorce his first wife Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn is obviously a proximal trigger for the English Reformation, this desire is itself rooted in fears of a succession crisis. Henry had no male heir, and everyone remembered the dynastic struggles over succession that we now call the ‘Wars of the Roses’. It was also rooted in related anxieties about the legitimacy of his Tudor regime; its claims were pretty thin and Henry was surrounded by people with claims equally good if not better than his. Even more fundamental were the conflicts between his centralising state system and the older form it was replacing, the threats inherently posed by the powerful landowning nobles in his realm, the change of priority from diplomatic matrimonial alliance with Spain to the need to ally his regime with powerful domestic potentates, the ongoing shift towards a more modern conception of England as a nation state, etc. All this stemmed from the same underlying distal cause as the European Reformation, namely the beginning of the shift from a feudal to a capitalist international system. And Henry was increasingly influenced by people with sympathies towards Protestantism and Evangelicalism, including Anne Boleyn and Thomas Cromwell. Despite his religious conservatism, people who told him that the new ideas included national royal authority over church authority were pushing at an open door. And this wasn’t just about his personal megalomania. He needed that kind of total authority in order to keep stability in his increasingly unstable world.

To imagine that a historical materialist view requires that every event be susceptible to a directly economic causal explanation is to catastrophically misunderstand historical materialism. Historical materialism is not a form of determinism or reductionism and does not claim that everything that happens in the social superstructure is immediately caused by some corresponding factor in the economic base. It would be entirely compatible with historical materialism if England had not gone Protestant, as many European countries did not, even with the underlying economic shift taking place, and even with that economic shift being the ultimate cause of the Reformation. A huge degree of contingency does operate in history. The English Reformation makes this abundantly clear, with the religious fate of the nation directly tied to the fluctuating natal, mortal, and marital fortunes of a family of monarchs. But even that is rooted in the material and the economic. The fact that England’s ultimate religious settlement was determined by the early deaths of Edward VI and then Mary I is to speak about a political system in which government policy derives from a single person, and monarchy is a material system with its roots in economic bases. Monarchy can look like a null hypothesis precisely because it can be described via a single person, and thus looks very human and mundane. Monarchy is actually a grotesquely strange way to organise a society, and only comes about as a result of an economic system which deforms social life to an enormous extent, namely: feudalism.

Capitalism grew inside feudalism. Feudalism is the term long used to describe the system – or complex of essentially similar economic systems – which dominated Europe from, roughly, the fall of the classic Roman Empire through to the rise of capitalism. The medieval era, or middle ages, in other words. (Distinct systems, sometimes similar in many respects, obtained in other parts of the world in the pre-modern epoch.) Feudalism itself grew out of the Roman system, in which large market-dominated cities guzzled the wealth produced by conquest, and by farms worked by slaves (generally people captured in conquest) or by near slaves (such as debt bondsmen). The old Roman slavery system fell apart but it gave birth to the feudal system, which was a manorial system of landholding in which local lords were granted rights over areas comprising productive land and the people – peasants – who worked that land. Peasants came in various forms. Serfs and villeins were basically tied to the land, and directly forced to produce surplus for their lord or lords in addition to their own subsistence. Lords ruled via castles and retinues of armed men. The system was a nest of reflexive obligations in which surplus, loyalty, and military service flowed upwards from bottom to apex (kings), and in which legal and military protections (supposedly) flowed back down from apex to bottom. As in the classical slave empires, the only real mechanism for economic growth in such a system (once the land was being exploited as efficiently as it could be under the material circumstances) was conquest. This was why the feudal system was wracked throughout its existence by wars stemming from competing claims on land – and the concomitant controversies caused by competing ideological justifications for those claims, which generally took a religious form. The ideological worldview dominating the feudal world grew directly from the economic form of that world, and took the form of elaborate metaphysical justification of the strict hierarchy. The overwhelmingly dominant expression of this was the Catholic Church which, again, grew from the old Roman system of centralised authority. In order to play its role as ideological authority, and as a result of the opportunities that role provided, the Church took the form of a massively wealthy trans-territorial feudal landowner. For most of its life, the medieval world did not have nation states in the same way we do, but they started to develop inside it as time went on, a byproduct of the growth of capitalist relations within the feudal system. The needs of competitive military accumulation caused a slow, cumulative build-up of technical improvements, and international trade, which caused productivity to increase. Trade and mercantile capitalism developed into extremely powerful centres of economic influence.

Increasingly, papal authority crunched up against the growing power of proto national states. Luther was far from the first to point out the hypocrisies, venalities, contradictions, and superstitions which had grown up within the established ideology and practice of the Catholic Church. His was the protest which ‘caught on’. Protestantism became a trans-European movement in a way that similar previous protests did not because Luther existed at a particular historical moment. The importance of the printing press has already been mentioned. Luther, unlike many similar critics of Church power before him, had the effect he had because he had networks of international trade in mass produced books, and rising literate classes to read those books. But there was also the issue of local rulers who would support and protect him (most notably Fredercik, Elector of Saxony) because he (or his ideas) helped to bolster their local power against the transnational power of the Church. Luther had the good fortune to exist in a moment which made his critique useful to loci of power in Europe which could use it, namely: the rulers of national states looking for ideological expressions – within the ruling ideology of Christianity – of their own drive for national economic and state independence from the trans-European power and property of the Catholic Church.

Protestantism grew in the protections offered by local rulers, increasingly powerful because of slowly accumulating increases in the productivity of labour and trade, and in the efficiency of military technology. As an ideology expressing this new reality, it consequently urged obedience to local state and crown authority on the part of the faithful. But it also grew as a result of popular support for its comparatively individualistic emphasis, for the possibilities it seemed to open up – despite the wishes of its founders – for egalitarian and liberatory change. This is why, in different places, the Protestant revolution took the form of both revolution from above and revolution from below. It therefore also grew from the dialectic of conflict between its own internal impulses, from the use of its doctrines by revolutionaries and the subsequent repression of those revolutions by princes who wanted it confined to an ideology of local power over transnational power and crown power over church power. It therefore expresses – and attempts to reconcile or solve – the inbuilt contradictions of capitalism, contradictions baked into its very structure: the contradiction between the new individuality of the ‘free’ worker who can/must sell their labour rather than stay tied to the land vs. the new forms of social hierarchy between new working classes and new middle classes, and the centralised state which capitalism needs in order to enforce the stability of such an anarchic yet stratified system of market and divisions of labour.

As Chris Harman put it in A People’s History of the World (1999):

Historians have wasted enormous amounts of time arguing over the exact interrelation between capitalism and Protestantism. A whole school influenced by the sociologist (and German nationalist) Max Weber has argued that Protestant values produced capitalism, without explaining where the alleged Protestant ‘spirit’ came from. Other schools have argued that there is no connection at all, since many early Protestants were not capitalists and the most entrenched Protestant regions in Germany included those of the ‘second serfdom’. Yet the connection between the two is very easy to see. The impact of technical change and new market relations between people within feudalism led to a ‘mixed society’—‘market feudalism’—in which there was an intertwining but also a clash between capitalist and feudal ways of acting and thinking. The superimposition of the structures of the market on the structures of feudalism led to the mass of people suffering from the defects of both. The ups and downs of the market repeatedly imperilled many people’s livelihoods; the feudal methods of agriculture still spreading across vast areas of eastern and southern Europe could not produce the yields necessary to feed the peasants as well as provide the luxuries of the lords and the armies of the monarchs. An expanding superstructure of ruling class consumption was destabilising a base of peasant production—and as the 16th century progressed, society was increasingly driven to a new period of crisis in which it was torn between going forward and going backward. Every class in society felt confused as a result, and every class looked to its old religious beliefs for reassurance, only to find the church itself beset by the confusion. People could only come to terms with this situation if they found ways to recast the ideas they had inherited from the old feudalism. Luther, Zwingli, Calvin, John Knox and the rest—and even Ignatius Loyola, who founded the Jesuits and spearheaded the Catholic Counter-Reformation—provided them with such ways.

November 27, 2024 @ 11:27 am

Jack, have you read or are you aware of the novel “Q” by the Italian anonymous collective ‘Luther Blissett’ (now ‘Wu Ming’)? I mention it because it’s pretty squarely on this sort of topic, though more what was going on in Europe at the time than England (the country is visited once for a couple of pages, mostly for a gag about how it’s always raining). But the narrative, spanning 1525-55, deals with exactly this, the fallout of the ongoing Reformation in terms of its political and economic ramifications as well as the obvious theological ones. The sections of the book set in Antwerp and Venice, or dealing with the Fugger banking family, are particularly overt in this respect; the writers depict a new world of globalised capital just peeping round the corner. But even earlier, in Frankenhausen and Munster, you’ve got a lot to do with the Bishops and the princes and Lutherans joining forces and pulling rank against radical peasant demands because of shared financial and political interests.

The context of the 1990s, when the book was written, is also just as important to the book as that of the 16th century, in that the four Italians who comprised ‘Luther Blissett’ were heavily involved with the Zapatistas and other radical peasant movements taking on neoliberal politics, and they’re writing at the turn of a millennium filled with similar forebodings about millennialism and apocalypticism as many of these anguished radicals of the 1520s and 1530s were, with similar concerns about the global financial system and its hostility to other ideas (especially in the decade of The End of History etc), but also drawing a link between the German Peasants’ War of 1525 and Muntzer’s proto-Communism with the Zapatistas and other movements of the 1990s.

That said, the book does not have the most progressive depiction of women there’s ever been, so just a forewarning if anyone does read it off the back of this comment.

December 1, 2024 @ 11:42 am

I’ve always found it an interesting piece of the transition from feudalism to capitalism that there was a whole class of people in feudalism which not only disappeared under capitalism, but the concept itself vanished almost completely from public consciousness. I was certainly taught to regard serfdom as being “basically the same as slavery with some technically differences you would not understand”, but fundamentally, serfs were considered something akin to a geographical feature – they “belonged” to the land as much as a forest or a mountain. And even insofar as that’s recognized today, the focus is on how that’s a lesser state than being a freeman, with little thought to the fact that the transition from serf to prole wasn’t any materially real sort of liberation – it wasn’t a “freeing them from being bound to the land” so much as capital deciding it was inefficient to let workers just HAVE a “place you belonged” for FREE.